A Comparison of Mechanisms Underlying Substance Use for Early

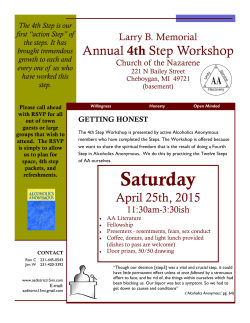

A Comparison of Mechanisms Underlying SubstanceUse for EarlyAdolescent Childrenof Alcoholics andControls* BROOKES.G. MOLINA, PH.D.* LAURIECHASSIN PH.D. ANDPATRICKJ. CURRAN,M.A. Departmentof Psychology, ArizonaStateUniversity,Tempe,Arizona 85287 evidenceof differential importancefor COAs and non-COAs of the parent monitoringand negative affect mechanisms.Parentalsocialization and negativeaffect mechanismssignificantlypredictedadolescent substanceuse regardlessof COA status. Differences did emergeregardingthe effects of age and parent educationon peer substanceuse and the effect of sociabilityon adolescentsubstance use. (J. Stud. Alcohol 55: 269-275, 1994) ABSTRACT. The currentstudyexamineddifferencesbetweenchildren of alcoholics(COAs) and controlsin parentmonitoring,stress- negative affect, and temperamentmechanismsunderlyingearly adolescentsubstanceuse. Using structuralequationmodeling, we tested whether these mechanismswere equally predictiveof substanceusefor both groups.We extendedan earlier studythat tested mediators of COA risk for substance use but did not examine COA status as a moderator of these mechanisms. Overall, we found no INDINGS thatchildren of alcoholics (COAs) areat increased risk for adult alcoholism has stimulated in- terest in uncoveringthe mechanismsunderlyingthis vulnerability (see Sher, 1991). Little is known, however, aboutalcoholand drug useamongCOAs duringearly adolescencewhich is a period of risk for substanceuse initiation (Johnstonet al., 1988). Research has suggested that adolescentsubstanceuse may result from multiple mechanisms includingpeermodelingand socialinfluence, deficitsin parentalsocialization,controland support,parent modelingand toleranceof use, and attemptsto cope with stress-induced negativeaffect (seeChassin,1984, for a review). However, it is unknown if the mechanisms underlyingsubstance use differ for high-riskadolescents (suchas COAs) comparedto the generaladolescentpopulation. If particularmechanisms were associatedwith substanceuse in a high-riskgroup,they would be of special interest for preventive interventionefforts. The current studytestedwhethermechanisms underlyingearly adolescent substanceuse differed for a sample of COAs and their non-COA peers. Multiple pathwaysto substance use have been posited to accountfor the increasedrisk for substanceuse among COAs. These mechanisms have included differential sen- sitivity to the positiveor negativeeffectsof alcohol,parent modelingof alcohol abuseand exposureto alcohol, and use of alcoholand drugsto cope with tendenciesto- Received:August4, 1992. Revision:February16, 1993. *This studywas supportedby National Instituteon Drug Abusegrant DA05227 to Laurie Chassin and Manuel Barrera, Jr. *BrookeS.G. Molina is now with the WesternPsychiatric Institute andClinic, Universityof Pittsburgh,3811O'Hara Street,Pittsburgh,Pa. 15213-2593.Correspondence shouldbe sentto her at this address. ward negativeaffective states(see Sher, 1991). Recently, Chassinand colleaguesfoundthat parentalalcoholismaffected early adolescentsubstanceuse throughstressand negative affect mechanismsand through impairmentsin parentmonitoring,both of which increasedthe probability of associationswith a peer network that supportedsubstance use behavior. Parent alcoholism stance use for examine COAs and controls. the role of COA Such a test would status as moderator of these mechanisms.The current study extendedChassin et al.'s work to addressthis issue:namely, are the processesthat place adolescentsat risk for substanceuse similar for COAs and non-COAs?The stress-negativeaffect mechanism was of specialinterest.Researchsuggeststhat young adult COAs derive greaterstressresponsedampeningbenefits of alcohol use than do their non-COA peers (Levensonet al., 1987). Consequently,COAs may be more likely to use substances to cope with stress-induced negativeaffective states.This hypothesissuggeststhat mechanisms involvingstressand negativeaffect may be more important to substanceuse among COAs than among nonCOAs. To test this prediction, we used the same sample and measuresreportedin Chassinet al. (1993) to compare parameterestimatesfor the model in Figure 1 for COAs and non-COAs. 269 was also associated with higher levels of temperamentalemotionalityin adolescentswhich raised risk for experiencingnegative affect. These findings were producedusing a community sample in which parent alcoholismwas directly ascertained and data were gatheredfrom multiple informants (Chassin et al., 1993). However,Chassinet al.'s studydid not include a test of whether the parent monitoring, negative affect and temperament mechanismswere equally predictive of sub- 270 JOURNAL OF STUDIES ON ALCOHOL / MAY 1994 Father's Monitoring Mother's Monitoring I Child's I . . ] .26(.26L '"-I Negative• Child's .34(.27) .,.•l Stress AffiliationsI Child's I .59(.6_0) withDrug-• Substance I Affect [•,. Using Peers [•. Use d3 Child's Emotionality I / •.14 (.20) • Child's Sociability FIGURE1. The hypothesized structuralmodelof mechanisms underlyingearly adolescent substance use. For presentational ease,the exogenous variablesof age, gender,parenteducation,currentparentalcoholconsumption, andtheir associated pathsare not shown.Pathcoefficientestimatesare standardized within eachgroup;estimatesin parentheses are for controlsandwithoutparentheses are for COAs. d l to d3 = structuraldisturbances. Solid linesindicatesignificanteffectsat p < .05 for bothgroups.Dashedlinesindicatemarginallysignificanteffectsfor bothgroups.(aThepathcoefficientfor sociability-•substance use is significantfor COAs [b = . 16, p < .05] but not for controls[b = -.04, NS].) Method Subjects Of a total sampleof 454 adolescentsand their parents, a subsampleof 327 familieswith completedata (provided by two parentsand the adolescent)was usedfor the anal- ysesreportedin the currentstudy. I Adolescents in this subsampleranged in age from 10.5 to 15.5 years (mean age = 12.7 years) and approximatelyhalf were female (n = 176). In addition, 178 adolescentshad at least one biologicalalcoholicparentwho was also a custodialparent (COAs), and the remaining 149 adolescentswere demographically matched controls with biological and custodialparentshavingno historyof alcoholism.(For additional information, see Chassin et al., 1993.) Recruitment Recruitment proceduresare presentedin detail elsewhere (Chassin et al., 1991, 1992). COA families were recruitedusing court records(full sample= 103), well- nessquestionnaires from a health maintenanceorganization (full sample= 22) andcommunitytelephonesurveys (full sample= 120). (One family was referredby a local VA hospital.)Demographicallymatchedcontrols(matched on ethnicity,family composition,adolescentage within 1 year and SES) with no historyof parentalcoholismwere recruitedover the telephoneusing reversedirectoriesto identifyfamiliesin the sameneighborhoods as COAs. Adolescentshad to be Hispanic or non-HispanicCaucasian and 10.5-15.5 years old, English-speaking,and without cognitivelimitationsthat would precludeinterview.Analysesto detect participationbias determinedthat magnitude of bias was small and unrelated to archival indicators ofalcoholism (seeChassin etal., 1991,1992). Procedure Familieswere invited to participatein a studyof adolescent developmentand substanceuse. Data were col- lectedby trainedinterviewersusingindividualcomputerassistedinterviewswith the adolescents and their parents. Interviewerswere blind to alcoholismstatusof the family. MOLINA, CHASSIN AND CURRAN 271 To minimize contamination,family memberswere inter viewed individually on one occasion by different interviewers; privacy was emphasized. Confidentiality Johnstonet al., 1988; •t = .92) and of how close friends was assured and reinforced would feel about the adolescent's use of these substances with a DHHS Certificate of Confidentiality. both occasionallyand regularly (seven items; ot = .93). The two scale scoreswere standardizedand averagedto representthe proximal peer environment. Measures The measuresof interest were drawn from a larger interview battery. (A completereport appearsin Chassin et al., 1993.) All variableswere incorporatedinto the hypothesized structural model as manifest indicators and constructionof these variables is describedbelow.2 Demographiccontrol variables. Child age, gender and averagelevel of parent educationalattainmentwere used as backgroundcontrol variables in the model. Parent alcoholism.Lifetime DSM-III diagnosesof alcoholism (abuseor dependence)were obtainedfrom parent interview usinga computerizedversionof the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (Robins et al., 1981). Predictor variables in the hypothesized structural model. Mother and father monitoring of child behavior was assessedby parent self-report(3 items, e.g., "I had a pretty good idea of [the child's] plansfor the day," Cronbach's •mother: .79, Cronbach'stlfather: .75). Child's current life stresswas how many of 22 negative, uncontrollable events marijuanaandotherdrugsbothoccasionally andregularly (six itemsadaptedfrom the Monitoringthe Futurestudy; had occurred in the last 3 months as reportedby parentsand adolescents. Adolescentsalso reported on four additionalpeer-relatedevents.Items were taken from the Children of Alcoholics Life Events Sched- ule (Roosa et al., 1988) and the General Life Events Schedulefor Children (Sandleret al., 1986) supplemented with several items from other children's life events sched- ules. For the structural model, the life stress variable was a multiple reportercompositemanifestvariable usingfactor scoreregressionweights.Child emotionalityand sociability were measured using a modification of the adult version of the Emotionality-Activity-SociabilityScale (EAS) (Bussand Plomin, 1984). Coefficientalphasfor the child, mother and father reports were, respectively,.72, .78 and .76 for emotionality (8 items) and .46, .62 and .60 for sociability (4 items). For the structural model, these two temperamentvariables were multiple reporter compositemanifestvariablescreatedusingfactorscoreregression weights. Child's negative affect was measured using child self-report of internalizing symptomatology (seven items from the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist; Achenbach and Edelbrock, 1981; ot = .78), selfderogation (seven items from Rosenberg's 1977 scale; ot = .81), and perceivedlossof control(three items from Newcomb and Harlow, 1986; ot -- .73). For the structural modeling, child's negative affect was a compositemanifest variablecreatedusingfactorscoreregressionweights. Affiliation with drug-usingpeerswas measuredusing the adolescent'sestimationof how many friends usedalcohol, The dependentmeasure:Adolescentsubstanceuse. Adolescentsself-reportedtheir frequencyof consumptionof beer/wine and distilled spirits (2 items), five or more drinks in a row (1 item), getting drunk on alcohol (1 item), and eight illicit drugs(8 items) all in the past 3 months.Responseoptionsrangedfrom (0) not at all to (7) every day. A singlesubstance use scorewas calculatedby summingthe responsesto the 12 items. A normalizing transformationwas used to reduce skewness(after trans- forming,skewness was1.75).3 Results Model specificationand adequacyof fit for the full sample Beforetestingfor differencesin pathestimatesbetween COAs and controls,the fit of the hypothesizedmodel in Figure1 wasestimated forthefull sample (n = 327).4 To account for covariation among the backgroundcontrol variables and the endogenousvariables, the model was first estimatedwith all pathsfrom child age, genderand parent educationfixed to zero; control paths with high modificationindices(-> 5) were successivelyfreed until noneremained.Only two pathswere significant:child age to child negativeaffect and child age to affiliations with drug-using peers. These two paths were included in the structural model. The hypothesized, structuralmodelfit the datavery well (X2 = 18.75,15df, p > .22, TLI = .98, BBI = .98).5 Moreover, examination of the residuals and modification indices further indicated that the observed variance/cova- riance matrix was adequatelyreproducedby the model in Figure 1. As describedin Chassinet al. (1993), lessparental monitoring was associatedwith greater adolescentaf- filiationwithdrug-using peers(bfather, smonitoring : --' 17, p < .01; binother, s monitoring = --.09, p<. 13) and with adolescentsubstance use (blather. s monitoring = --'16, p < .01); affiliation with drug-usingpeers was in turn associated with increased adolescent substance use (b = .63, p < .01). Adolescentstresseventswere significantly related to adolescentnegative affect (b = .38, p < .01) and negativeaffect was in turn significantlyrelated to affiliation with drug-using peers (b = .29, p < .01). Negativeaffect was also marginallydirectly related to adolescentsubstanceuse (b = . 11, p < . 10). Adolescentemotionalitywas associatedwith higherlevelsof adolescentnegativeaffect (b = .18, p < .05), while ad- 272 JOURNAL OF STUDIES ON ALCOHOL TABLE1. Comparisons of modelparameters betweenCOAsandcontrols Model X2 (df) TLI BBI 7•it-t(df) 131.71'(81) .91 .85 - 51.44(42) .97 .94 80.27*(39) 46.86 (41) .98 .95 4.58* (l) 45.07 (40) .98 .95 1.79 (1) 40.30 (39) 1.00 .95 4.77* (1) 39.02 (38) 1.00 .96 1.28 (1) 34.94 (37) 1.00 .96 4.18' (1) 3. Age-->peersfree within groups 4. Parenteducation-->peers added to model, invariant betweengroups 5. Parent education-->peers free within groups 6. Sociability-->substance use added to model, invariant between groups 7. Sociability-->substance use free within groups Notes: "Invariant" refers to specifiedparameter(s)estimatedas equal for COAs and controls."Free within groups"refersto specifiedparameter(s) estimatedas not equal for COAs and controls.Path coefficient parameterestimatesare denotedby arrowssurrounded by the relevant constructs(e.g., the effect of child age on affiliationswith drug-using peersis denotedby age-->peers). Peers= affiliationswith drug-using peers.X2a, ,- indicates testof significant changein modelfit fromthe previousmodel. *p < .05. becauseof previouslyestablishedlinks betweenparent alcoholism and environmental stress; Roosa et al., 1988). 1 for Model 2. The hypothesizeddifferencesbetween COAs and controls with regard to the relation between negative affect 2. Variances/covariances for exogenousvariables, disturbances for endogenous variables,free within groups 1994 Model fit improvedsignificantlyand is displayedin Table 1. All parameterestimates invariant / MAY *p < .001. and substance use were not found. withdrug-using peers(b = . 19,p < .01).6 indices use were added to the model and released from invariance (Models 5 and 7, respectively).Final path coefficientsfor both groupsare in Figure 1. Child age was more strongly relatedto affiliationswith drug-usingpeersfor COAs than for controls,parenteducationwas more stronglyrelatedto affiliations with drug-usingpeers for controlsthan for COAs, and sociabilitywas more stronglyrelatedto child substance use for COAs olescentsociabilitywas associatedwith less negative affect (b = -.28, p < .01) but also with greateraffiliation Modification associatedwith thesetwo paths (negative affect to affiliations with drug-usingpeers, negative affect to substance use) were very low (<- 1) both beforeand after freeing the parametersdescribedabove, indicatinga lack of significant differencesin the paths from negative affect for the two groups.However, severaldifferencesbetweengroups were identified by high modificationindices.In Table I it can be seen that there was significant improvementin modelfit after the path from child age to affiliationswith drug-usingpeerswas releasedfrom invariance(Model 3) and after the paths from parent educationto affiliations with drug-usingpeers and from sociability to substance than for controls. There were no other indications of reliably significant differencesbetween groups in any of the remaining path coefficient estimates. ? FinalmultipleR2 estimates for childnegative affect, affiliations with drug-usingpeers and child sub- Model fit for COAsand controls stanceuse were .36, .38, .54 for COAs, and .43, .32, .51 An iterative series of cross-groupanalyseswas conductedto determinethe presenceof significantdifferences for controls, respectively.These estimateseach differed significantlybetweengroupsat p<.05 as indicatedby significantincreasesin the modelchi squarewheneachesti- between COAs matewasindividually specified asinvariant (•2diff , 1 df, and controls in overall model fit and in individualparameterestimates.First, the overallfit of the structuralmodel in Figure I was comparedfor COAs and controls.A cross-groupcomparisonwas conductedwith all parameter estimates specified as invariant across groups.The resultingfit, displayedin Table I for Model 1, was less than adequateand confirmedthe presenceof significantdifferencesin overall model fit. ranged from 4.60 to 6.30, all p<.05). Overall, despite thesedifferencesin predictedvariance, the findings suggestedthat the parent monitoringand stressand negative affect mechanismswere similarly related to substanceuse for COAs and controls.a Discussion Second, differences between COAs and controls in indi- vidual parameterestimateswere examined.The presence of multiple modificationindicesgreaterthan five indicated that the variance/covariancematrix for the exogenous variables and the disturbances associated with the endogenousvariables were significantlydifferent across groups.Theseparameters werefreed(1) to improvemodel fit for both groupsin order to have increasedconfidence in path coefficientdifferencesand (2) becausedifferences in the variance/covariance and disturbanceparameterestimatesacrossgroupswere consistentwith theory-basedexpectations(e.g., greatervariabilityin stressamongCOAs The goal of this study was to considerpossibledifferences between COAs and non-COAs in the mechanisms underlyingearly adolescentsubstanceuse. In particular, we hypothesizedthat negative affect would relate more stronglyto substanceuse (both directly and indirectlyvia involvement with substance-usingpeers) for COAs than for non-COAs. Our findings did not supportthis prediction. Rather,our findingsindicatedthat parentmonitoring and stressand negative affect mechanismswere significantly related to substanceuse for both COA and nonCOA adolescents,and the degreeof associationwas not MOLINA, CHASSIN differentbetweenthe two groups.This finding is notewor- thy in view of Chassinet al.'s (1993) finding that COA parentsmonitoredtheir childrenless and COAs experienced significantlymore stressand negativeaffect than controls. Thus, although early adolescentCOAs show higherlevelsof substance use and higherlevelsof these particularpsychosocial risk factors,thesemechanisms underlying substance use appearto operateboth for those with and withoutalcoholicparents.Thesefindingssuggest that programsaimed at teachingcopingskills or at improvingparentmanagement couldbe usefulregardless of parentalcoholismhistory. Our finding that negative affect mechanismsoperated similarlyfor COAs and controlsmay be due to the early agesof our adolescents. We purposefullysampledyouth in the 10-15year old age rangewith the aim of capturing the period of risk for substanceuse initiation (Johnston et al., 1988). This strategy resulted in our having few substance-abusing or substance-dependent adolescents-- the populationtypicallydescribedwith regardto negative affect regulationmotivesfor substanceuse. Particularly strongnegative affect regulationmotives for use among COAs (comparedto non-COAs) may not emerge until older agesand/orhigherlevelsof use. Evidencethat girls, more than boys, report drinking to cope with stressors (Windie, 1991) suggeststhat gender ratherthan parentalcoholismmay moderatethe impactof stress-negative affect mechanisms on substance use. However, Chassinet al. (1993) did not find genderdifferences in the stressand negativeaffect mechanismwhen testing their mediationalmodel for boys and girls separately.A moderatingeffect of gendermay not emergeuntil later in AND CURRAN 273 that put COAs at risk for substanceuse. These interactions may include friends who are deviant in other ways (not directly reflected in their substanceuse) or interactions with drug-usingindividualswho are not perceivedas "friends" (e.g., older relative, neighbors).Alternatively, sociabilitymay not only elevate associationswith deviant peers but also may serve as a marker for a disinhibited behavioralstyle that hasbeen associatedwith the development of alcoholism, with substanceuse and with greater stressresponsedampeningeffects of alcohol (Sher and Levenson, 1982; for reviews, see Tarter et al., 1985; Windie, 1990). These mechanisms deserve future research at- tention in explaining the differential risk for adolescent substanceuse associatedwith parent alcoholism. Overall, our findings suggestedthat parent monitoring and negative affect mechanismssignificantly predicted early adolescentsubstanceuse regardlessof parental history of alcoholism.Our failure to find a predictedstronger effect of the negative affect mechanismfor COAs persistedindependentlyof our considerationof currentparent alcoholconsumption.However,differentdefinitionsof parental alcoholism,different agesof COAs or different operationalizationsof constructsmight all affect findings (Sher, 1991), and our results are in need of replication with other samplesand longitudinaldesigns. Acknowledgments The authorsthank Mark Reiserand StephenWest for statisticalconsultation and comments on this article. Notes adolescence. Differences between COAs and non-COAs were found for the effectsof child age and parenteducationon affiliations with drug-usingpeers, and for the effect of sociability on child susbtanceuse. Age was more strongly relatedto affiliationswith drug-usingpeersfor COAs than for controls.In other words, as they approachmiddle adolescence,COAs may escalatemore rapidly into a highrisk environmentmarked by relatively greater immersion in a drug-tolerantpeer network. Furthermore,for COAs, theseassociations were independent of socioeconomic status (as defined by parent education). For controls, however, a drug-tolerantpeer environmentwas related to parent education, suggestingthat broader sociocultural factorsaffect peer choice in the absenceof a family history of alcoholism. We expectedsociability to exert all of its influence throughaffiliationswith drug-usingpeers.Thus, our finding that sociabilitywas directly (and more strongly)related to substance use for COAs than for non-COAs was surprising.Perhapsour operationalizationof peer influence as friends who use drugs or who tolerate drug use was too narrow to captureall of the social interactions When investigatingthe mechanismsunderlyingthe relation between COA statusand adolescentsubstanceuse, Chassin et al. (1993) tested their hypothesized mediationalmodelusingthe subsample of families with complete data (n = 327) and the entire sample of two-parent families(n = 416) wheredata for one noninterviewedparentwas imputed (BMDP AM program, Version 5; see also Little and Rubin, 1987). Similar findings were producedusing the samplesof 327 and 416 suchthat, with only one exception,all pathsreportedas significant usingthe sampleof 327 remainedsignificantusingthe sampleof 416. The one changewas that the effects of emotionalitybypassed negativeaffect to predictassociations with drug-usingpeers.In addition, severalpathsthat were nonsignificantor marginally significant in the original model became significant using the imputed data: mother'salcoholismwas significantlyassociatedwith lower levelsof maternalmonitoring,lower maternalmonitoringwas associatedwith higher levels of peer drug use and father's alcoholismwas significantlyassociated with adolescent's heightenedemotionality.Thus, reestimatingthe modelusingimputeddata for the total sampleof twoparentfamiliescloselyreplicatedthe findingsbasedon the sampleof 327 two-parentfamilies with completedata. In addition, comparisonswere performedbetweentwo-parentand single-parentfamilies (t testsand chi squares)to assesswhether the exclusionof single-parentfamilies (33 single mothersand 5 single fathers)introducedbias into the sample.The groupswere compared on a variety of demographic variablesas well as on all variablesrepresentedin the hypothesizedmediationalmodel tested by Chassin 274 JOURNAL OF STUDIES ON ALCOHOL et al. (1993). There were no significant differencesbetween the single-parent and two-parentfamiliesfor 18 of the 29 comparisons including, most importantly,the adolescent'salcohol- or drug-use outcomes.Of the significantdifferencesthat were found, the directions of the differenceswere not consistentin terms of puttingeither the single-parentor the two-parentfamily at higher risk. Moreover, the differencesbetweenthe two groupswere generallyminor. 2. Compositemanifestvariablesfor constructsinvolvingmultiple reporters(stress,emotionality,sociability)or multipleindicators(negative affect) were createdto preserveinformation from the multiple reportersand multiple indicators.The inclusionof theseas latent variableswas untenablegiven the requirednumberof parametersand current sample size which would have exceededBollen's (1989, p. 268) suggestion to haveat leastseveralcasesper free parameter. To createthe multiplereportervariables,weightedlinearcomposites of mother,fatherandchild reportof stress,emotionalityand sociability were calculatedusingfactorscoreregressionweightstaken from a singlethree-factormeasurement modelof theseconstructs. The negative affect variable was constructedsimilarly using weights taken from a single one-factormeasurementmodel (see Loehlin, 1987, for a more detaileddiscussionof factor-scoreregressions).Compositereliabilities were calculatedfor each manifestvariable using the estimatesof error and total varianceproducedby the measurement model (Lord and Novick, 1968, p. 86). The error terms for thesemanifest variables,and for affiliationswith drug-usingpeersand child's substanceuse, were then set to one minus the reliability multiplied by the varianceof the indicator.(For additional details concerningthese / MAY 1994 exogenousvariable affectingchild's substanceuse. This singlemanifest variablewas not includedin the original model testedabovebecause(a) Chassinet al. (1993) determinedthat effectsof parental alcohol consumptionwere different for mothers and fathers, and (b) becauseinclusionof both motherand fatheralcoholconsumption in the current article was untenabledue to the requirednumberof parametersandsamplesize. However,in an effort to approximatethe effectof currentparentdrinking,a singlemanifestvariablewas createdusingparentself-reportof alcoholquantityand frequencyof use in the past 3 months.Quantity-frequency productswere calculated separatelyfor eachparentand naturallog transformations were used to reduce skewness below 1.00 as in Chassin et al., 1993. Of the two parentreports,the one reportinghigher quantity-frequency was chosenin orderto reflect currentparentalalcoholconsumption. The predicted paths of theoreticalimportance(i.e., in Figure 1) were all replicated, with parent monitoringand stressand negative affect mechanismssignificantlyrelatedto substanceuse for both COA and non-COA adolescents. Current parentdrinking was significantlyrelatedto child'ssubstance usefor both COAs (b = .14, p • .01) and controls(b = . 13, p • .01), and all of the groupdifferencesin path coefficients wereconfirmed. FinalmultipleR2 estimates were:child's negativeaffect, .36; affiliationswith drug-usingpeers, .38; child's substance use, .56 for COAs; and .43, .32 and .54, respectively,for controls;and these estimatesdiffered significantlybetweengroups (p • .05). The final model reproducedthe observedvariance/covari- ancematrixvery well (•2 = 40.07, 42 dr, p > .55, BBI = .96, TLI = 1.00). measures see Chassin et al., 1993). 3. The normalizingtransformation was conductedfor the full sampleof 327 to retain a common metric for the substance use variable COAs and controls--a requirementfor comparingcovariancestructuresacrossgroups(Joreskogand Sorbom, 1989). 4. All analyseswere basedon the variance/covariance matrix in LISREL VII under maximum likelihood estimation. 5. The Tucker-Lewis (TLI) and Bentler-Bonnett(BBI) indices of incre- mentalfit rangefrom 0 to 1.00; Bentierand Bonnett(1980) recommend .90 as a minimal criterion for acceptablemodel fit. 6. Parameterestimates(b's) are standardized.Whenpresentedfor crossgroup analyses,b's are taken from LISREL'S within-groupstandardized solution. 7. One final modification index equal to 6.22 remained for the path from emotionalityto negativeaffect. When this path was freely estimatedwithin groups,emotionalitywas significantlyrelatedto negative affect for controls(b = .34, p < .01) but not COAs (b = .09, NS) and model fit improvedsignificantly(•2a,rr= 6.52, I df, p < .05). However,the estimatedcorrelationsbetweenemotionality and stressexceeded1.0 for both groupsand differedslightlyin magnitudebetweenCOAs and controls,promptingconcernthat the path coefficientdifferencewasunstableanddueto differentialcollinearity betweengroups.To test the possibilitythat over-correctionfor measurementerror causedthe out-of-boundcorrelationand, subsequently, the group differencesin the path coefficientestimates,the final cross-group modelwas testedwith the measurement errorsfor stress andemotionality setto zero(X2 = 31.49, 37 dr, p > .72). Statistically significantrelationsbetweenstressand negativeaffect and between emotionalityand negativeaffect were found for both groups, but the modificationindicesno longersuggested a differencebetween groups in the relation between emotionality and negative affect. Therefore,althoughthe relationsamongstress,emotionalityandnegative affect were reliably significantboth with and without correction for measurement error, the COA/non-COA difference in the relation betweenemotionalityandnegativeaffectwasdeterminedto be dueto over-correction for measurement References for error and therefore unstable. 8. To determinewhetherour findingswere independent of currentparent drinking, the seriesof cross-grouptestsconductedabovewas repeated with current parent alcohol consumptionas an additional ACHENBACH,T.M. ANt) EDELBROCK,C. Behavioral Problems and Com- petenciesReported by Parentsof Normal and DisturbedChildren Aged Four throughSixteen, Chicago:Univ. of ChicagoPress, 1981. BENTLER,P.M. AND BONNETT,D.G. Significancetestsand goodness of fit in the analysisof covariancestructures.Psychol.Bull. 88: 588606, 1980. BOLLEN,K.A. StructuralEquationswith Latent Variables, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc_, 1989. Buss,A.H. ANDPLOMIN,R. Temperament: Early DevelopingPersonality Traits, Hillsdale, N.J.: LawrenceErlbaum Assocs.,Inc., 1984. CHASSIN, L. Adolescent substance use and abuse. In: KAROLY, P. AND STEFFEN,J.J. (Eds.) Advancesin Child Behavioral Analysis and Therapy,Vol. 3, Lexington,Mass.:LexingtonBooks, 1984,pp. 99152. CHASSIN, L., BARRERA,M., JR., BECH, K. AND KOSSAK-FULLER,J. Recruitinga communitysampleof adolescentchildrenof alcoholics: A comparison of threesubjectsources.J. Stud. Alcohol53:316-319, 1992. CHASS•N,L., PILLOW, D.R., CURRAN, P.J., MOLINA, B.S.G. AND BAR- RERA,M., JR. The relationof parentalcoholismto early adolescent substanceuse: A test of three mediating mechanisms.J. Abnorm. Psychol. 102: 3-19, 1993. CHASSIN,L., ROGOsCH, F. ANDBARRERA, g. Substance useand symptomatologyamongadolescentchildrenof alcoholics.J. Abnorm. Psychol. 100: 449-463, 1991. JOHNSTON,L., O'MALLEY, P. AND BACHMAN,J. Illicit Drug Use, Smoking,andDrinkingby America'sHigh SchoolStudents,College Students,and YoungAdults, 1975-1987.Preparedfor the National Institute on Drug Abuse, DHHS PublicationNo. (ADM) 89-1602, Washington:GovernmentPrinting Office, 1988. JORESKOG, K.G. AND SORBOM, D. LISREL 7: A Guide to the Program and Applications,Chicago:SPSSInc., 1989. LEVENSON, R.W., OYAMA, O.N. AND MEEK, P.S. Greater reinforce- ment from alcoholfor thoseat risk: Parentalrisk, personalityrisk, and sex. J. Abnorm. Psychol.96: 242-253, 1987. MOLINA, CHASSIN LITTLE, R.J.A. AND RUBIN, D.B. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1987. LOEHLIN, J.C. Latent Variable Models: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and StructuralAnalysis, Hillsdale, N.J.: LawrenceErlbaum Assocs., Inc., 1987. LORD, F.M. AND NOVICK, M.R. Statistical Theories of Mental Test Scores,Reading,Mass.:Addison-Wesley PublishingCo., Inc., 1968. NEWCOMB, M.D. AND HARLOW, L.L. Life events and substance use amongadolescents: Mediatingeffectsof perceivedlossof controland meaninglesshess in life. J. Pets. Social Psychol.51: 564-577, 1986. ROBINS, L.N., HELZER, J.E., CROUGHAN, J. AND RATCLIFF, K.S. National Instituteof Mental Health DiagnosticInterview Schedule: Its history,characteristics, and validity. Arch. Gen. Psychiat.38: 381-389, 198I. ROOSA,M.W., SANDLER,I.N., GEHRING, M., BEALS, J. AND CAPPO, L. The children of alcoholics life-events schedule: A stress scale for childrenof alcohol-abusing parents.J. Stud. Alcohol 49: 422-429, 1988. ROSENBERG, M. Conceiving the Self, New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1979. AND CURRAN 275 SANDLER, I., RAMIREZ, R. AND REYNOLDS, K. Life stress for children of divorce, bereaved,and asthmaticchildren. Paperpresentedat the annualmeetingof the American PsychologicalAssociation,Washington, D.C., 1986. SHER,K.J. Childrenof Alcoholics:A Critical Appraisalof Theory and Research,Chicago:Univ. of ChicagoPress,1991. SnER, K.J. AND LEVENSON, R.W. Risk for alcoholism and individual differencesin the stress-response-dampening effectof alcohol.J. Abnorm. Psychol.91: 350-367, 1982. TARTER,R., ALTERMAN,A. AND EDWARDS, K. Vulnerabilityto alcoholismin men: A behavior-geneticperspective.J. Stud. Alcohol 46: 329-356, 1985. WINDLE,M. Temperamentand personalityattributesof childrenof alcoholics. In: WINDLE, M. AND SEARLES,J.S. (Eds.) Children of Alco- holics:Critical Perspectives,New York: Guilford Press, 1990, pp. 129-167. WINDLE,M. Genderdifferencesin adolescentsubstance use: A personenvironmentperspective.Paper presentedat the annual meeting of the American PsychologicalAssociation, San Francisco, Calif., 199 I.

© Copyright 2026