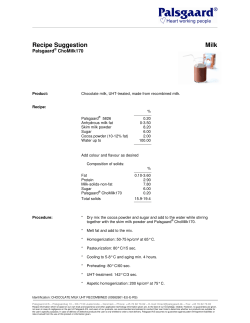

Bi®dobacterium spp. and Review