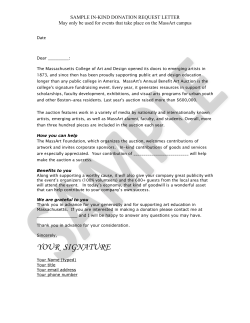

Document 108559