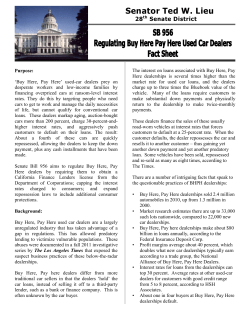

Original Article