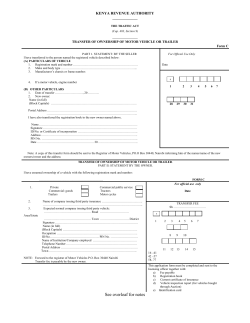

Document 110544