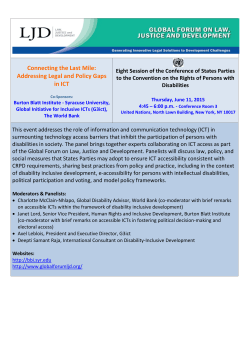

Closing the Feedback Loop: Can Technology