An evaluation methodology for hotel electronic channels

ARTICLE IN PRESS Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 An evaluation methodology for hotel electronic channels of distribution Peter O’Connora,*, Andrew J. Frewb a b IMHI, ESSEC Business School, Ave Bernard Hirsch, BP 105, Cergy Pontoise 95021, France Faculty of Business and Arts, Queen Margaret University College, Edinburgh, EH8 12TS, UK Abstract Electronic channels play an increasingly important role in hotel distribution, with most companies utilising a portfolio of channels to reach the customer in an effective manner. However channels cannot simply be added ad infinitum as they emerge; system complexity, technical factors and the management overhead associated with using multiple channels mean that choices must be made between alternative solutions. However, little is understood about how an electronic channel of distribution might be best evaluated. This study, combining both qualitative and quantitative approaches through a Delphi study, explored expert opinion on the key factors involved. Factors generated in the initial round of the study were subsequently refined, rated and ranked by the expert group to identify the key factors for consideration in both the channel adoption and continued use decision making process. In contrast to existing literature on channel evaluation, this revealed that operational and performance factors, rather than financial or strategic issues, should be of prime consideration in the adoption process. r 2003 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Electronic Distribution; Tourism; Hotels; Electronic commerce 1. Introduction Despite a well-recognised conservatism in the adoption of new technologies, electronic distribution systems have quickly gained widespread acceptance in today’s hotel sector. Effective distribution is especially important as the key (accommodation) product is highly perishable and sold in a market characterised by high capital *Corresponding author. Tel.: +33-1-3443-3177; fax: +33-1-3443-1701. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (P. O’Connor), [email protected] (A.J. Frew). 0278-4319/$ - see front matter r 2003 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2003.10.002 ARTICLE IN PRESS 180 P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 costs, increasing competition and shrinking margins (Vialle, 1995). The sale of each room, each night at the optimum price is critical to the overall profitability of a hotel (WTO, 1991). Although demand is increasing, achieving this objective has become increasingly difficult as the supply of hotel rooms is increasing at an even faster rate. Distribution systems play a key role in overcoming this challenge. Hotel distribution channels have two (main) separate yet interrelated functions; to provide consumers with information to help them in their purchase decision; and to facilitate the purchase itself (Middleton and Clarke, 2001). Effective information distribution is important since consumers are dependent on accurate, timely, high quality information to help differentiate among competing properties (Poon, 1994). Convenience, both in terms of finding appropriate information and facilitating reservations and payment processes is also critical (Castleberry and Hempell, 1998). Intermediaries especially have an interest in handling the most easily sold products and may well use competing suppliers if their product is more easily accessible (Bennett, 1993). One of the key enablers in distributing information and making the reservations process more convenient is information technology. However, hotel electronic distribution systems are currently in a state of transition as a result of technological advancements, new and emerging players and a shift in the balance of power among suppliers, buyers and intermediaries (O’Connor, 1999). Distribution costs are rising due both to the increasing number of intermediaries involved in the hotel distribution process, and the complex technological infrastructure needed to support distribution to a growing spectrum of potential channels (Connolly, 1999). The decision as to which channel(s) to use has become increasingly complex, and hotel managers currently have little guidance to help them determine which best match their needs (Weill, 1991). To investigate ways of addressing this, a (Delphi) study was undertaken to identify factors that should be taken into consideration when evaluating hotel electronic channels of distribution and a prioritised portfolio of factors was generated for consideration in both the channel-adoption and continued use decision making processes. 2. Distributing the Hotel product According to Connolly (1999) ‘‘merchants have wrestled with determining the best approaches to delivering their products to the marketplace since the early days of farmers’ markets’’. This challenge still exists today and has become more difficult in our ever-changing, increasingly competitive and global marketplace. Hotel channels of distribution provide ‘‘sufficient information to the right people at the right time and in the right place to allow a purchase decision to be made, and provide a mechanism where the consumer can make a reservation and pay for the required product’’ (Go and Pine, 1995). While extensive use is made of both direct selling and intermediaries, developments in information and communications technologies have presented powerful new possibilities for hotel distribution. Digital convergence, supported by miniaturisation, portability, declining costs and more powerful applications, are part of the trend driving computers to ubiquity in everyday life ARTICLE IN PRESS P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 181 (Negroponte, 1995). This has given rise to a digital economy where speed, agility, connectivity and the ability to amass and subsequently employ knowledge are key competitive ingredients (Tapscott, 1996). In the hotel sector, distribution channels represent the quintessential example of this convergence of technology, communications and content. Within tourism, the potential of electronic distribution was first demonstrated by the airline sector. Systems originally developed to help manage seat inventory were forwardly integrated into travel agencies (Knowles and Garland, 1994), giving agents direct access to information about flights, availability and pricing, and also facilitating direct bookings. The product portfolio of these systems was subsequently broadened, with hotel rooms being one of the first complementary products added to the developing Global Distribution Systems (GDS). However, as the database structure was originally designed for use with the airline product, it proved unsuitable for use with the more diverse hotel product. As a result, large chains developed their own systems with more appropriate data architectures, and subsequently interfacing them with the GDS. Independent hotels and smaller chains used alternative strategies, including outsourcing, joining a marketing consortium or making use of public funded Destination Management Systems (O’Connor, 2002). This effectively was the state of play at the beginning of the 1990s, with each system co-operating in a mutually beneficial relationship. However, the development of electronic commerce on the Web had a profound effect on hotel distribution. In addition to cooperation, systems started to compete by offering information and reservation services directly to the consumer (Coyne, 1995). Channels became increasingly interconnected as intermediaries formed strategic alliances in an attempt to develop multiple routes to the customer. New intermediaries and business models have appeared, and while the original electronic channels were linear, closed and dedicated, the emerging distribution model is multi-dimensional, open and flexible, with the majority of participants able to distribute to customers using a variety of different routes. Both the number of channels and the complexity of the network continues to increase, and the distinction between channels has become less clear as the systems become interconnected at multiple levels (Anderson Consulting, 1998). Since no one distribution channel is likely to dominate in the near future, hotels need to use a portfolio of channels to reach the marketplace (Middleton and Clarke, 2001). However, not all channels are equal and thus companies must carefully weigh their decisions in light of their organisational goals and performance standards (Crichton and Edgar, 1995). Some authors claim that selecting ‘‘an appropriate distribution channel is paramount to success and important if hotel firms are to grow top line revenues and control overhead, yet the number of choices facing hospitality executives is overwhelming’’ (Connolly and Olsen, 2000). Which channel (or combination of channels) should a hotel be using? Both the ever-increasing complexity of the distribution network and the rapid pace of change make this a difficult question to answer. Yet increased competition, scarcity of capital and rising distribution costs make management of electronic distribution channels essential. The question arises, therefore, of how to evaluate a hotel electronic channel of distribution. In the past, many companies did not perform such evaluations, ARTICLE IN PRESS 182 P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 preferring instead to adopt a ‘‘shelf space’’ approach, including their inventory on multiple simultaneous channels on the premise that more is better as it increases product visibility and thus the chance of selection by the customer. However, as the number of channels used increases, system complexity also increases, raising the management overhead and technological infrastructure required (Connolly, 1999). A more discriminating approach, balancing the merits and costs associated with each alternative, is needed. Budget airlines have long recognised the value of this strategy (Dev and Olsen, 1998), e.g. EasyJet has chosen not to participate in the GDS even though they [GDS] distribute the majority of airline seats worldwide and service the powerful travel agent market. Instead customers are encouraged to book directly, either over a toll-free number or over the company’s Website, thus saving on GDS fees and travel agent commissions. However, such a decision such as this can only be taken after a thorough evaluation of each option (Olsen and Zhoa 1997). Others (Lewis and Chambers, 1995) claim that such channel management is the backbone of distribution. Similarly, Andersen Consulting (Anderson Consulting, 1998) maintain that hotel companies urgently ‘‘need to get better at managing their channels, understanding the profitability of each and developing levers to divert traffic through one channel or another’’. 3. Evaluating electronic channels of distribution—a theoretical perspective As investment in IT-related projects tends to be substantial and suffers from a high failure rate, a considerable literature base exists on IT evaluation techniques (Remenyi and Sherwood-Smith, 1999). Perhaps the best starting point is an understanding of what is meant by evaluation. According to Ballantine and Stray (1999), evaluation is the process of establishing, by quantitative and/or qualitative means, the worth of an investment. Similarly Symons (1991) defines evaluation as ‘‘a process incorporating understanding, assessment and sometimes measurement of some sort against a set of criteria’’, while Remenyi and Sherwood-Smith (1999) define evaluation as ‘‘a conscious or an intuitive process whereby one weighs up the value added by a particular act/situation’’. Although the process can be intuitive, more formal evaluation techniques are prevalent in the case of large scale capital investments such as those involving distribution (Ballantine and Stray, 1999). In the following section, the techniques identified are grouped into economic and noneconomic approaches to facilitate discussion. While there is overlap, in this case, it is unimportant as the objectives are firstly to highlight the complexity of the evaluation process as it relates to information technology related projects, and secondly to bring some clarity to the range of techniques available. 4. Economic approaches As with any other asset, investment in the use of a distribution channel must be justified from a financial perspective (Griffin, 1997). For that reason financial ARTICLE IN PRESS P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 183 analysis techniques (include cost benefit analysis, value added approaches, productivity based approaches and capital appraisal) are the most commonly suggested (Avison and Horton, 1988). However, difficulties in assessing the monetary contribution of IT based systems limit the utility of such approaches (Lefley, 1996). With financial techniques, both costs and benefits are assumed to be well defined, direct and short-term (Hopwood, 1983), however, in reality there are a large number of unknowns, uncertainties and assumptions. Nearly 75% of all IT investments have no easily calculated business value (O’Brien, 1997) because instead of hard dollar costs benefits, they generate indirect, qualitative and contingent impacts that are difficult to quantify (Banker and Kauffman, 1993). Yet, despite being based on subjective judgement, typically in financial calculations every cost or benefit is shown as a single, precise number. And, because the evaluation must be done a priori, such numbers are based on forecasted cash flows and thus are to a large extent fictional (Weill, 1991). In any case, identifying the economic contribution may be difficult as IT projects frequently cross organisational boundaries and are often part of a string of interrelated investment decisions (some prior and some future) with the result that their effect is difficult to isolate from external factors (Applegate and McFarlan, 1996). Furthermore, evaluating electronic channels is made even more difficult by the speed at which this arena is current developing (Middleton and Clarke, 2001). And lastly, even if appropriate data could be obtained, today’s financial models are acknowledged to be insufficiently sophisticated to evaluate such investments (Applegate, 1999). Current techniques originated in the manufacturing economy, where the test of an investment’s worth is based on ‘‘effectiveness and productivity gains, as realised in terms of labour savings, increased output and lower unit costs’’ (Connolly, 1999). As such, they tend to focus on cost displacement, omit strategic implications, be biased towards short term returns, set unjustly high hurdle rates in situations involving high perceived risk and do not place enough emphasis on drivers of value such as customer satisfaction, innovation and quality (Ittner and Larcker, 2000). Thus while economic approaches are objective, theoretically well grounded, and undoubtedly the most commonly used, their effectiveness in evaluating information technology related projects is clearly limited. 5. Non-economic approaches As economic approaches are increasingly seen as insufficient, a range of other methodologies have been proposed (Leonard and Mercer, 2000). Supporters of these alternative approaches argue that the drivers of success in many industries are ‘‘intangible assets’’ such as intellectual capital and customer loyalty, rather than the hard assets shown on the balance sheet. Thus while economic techniques focus on performance against accounting yardsticks, non-economic measures encompass a wider range of factors that may be important in achieving profitability, competitive strength and longer-term strategic goals (Ittner and Larcker, 2000). Consider, for example, investments in research and development. Under normal accounting rules, ARTICLE IN PRESS 184 P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 these must be charged for in the period incurred, so reducing profits. However, successful R&D improves future profits if brought to market—a fact ignored by most economic evaluation methodologies (Ittner and Larcker, 2000). While IT projects must obviously be evaluated in terms of their technical feasibility and effect on existing systems as well as their performance, usability and reliability, many observers now stress the importance of assessing the contribution of the system to the organisation’s strategic position (McFarlan, 1984). Traditional models of competitive advantage are based on Porter’s five forces model, with strategic advantage resulting from when technology helps to achieve economies of scale, reduce costs, create barriers to entry, build switching costs, change the basis of competition, add customer value, alter the balance of power with suppliers, provide first mover effects, or generate new products (Applegate and McFarlan, 1996). Competitive advantage and strategic necessity confound traditional financial analyses as investment yield results over time rather than in the short run (Clemons and Weber, 1990). Taking a more strategic viewpoint balances the short- and longterm benefits against the initial capital expenditure, ongoing costs and other factors (Smith David and Grabski, 1996). However, as technology becomes a strategic issue, measurement difficulties are enhanced (Brady and Saren, 1999). In addition to the difficulty in quantifying results, ‘‘IT is a multidimensional object, its value can be looked at differently depending on the vantage point chosen’’, making it difficult to calculate the tangible benefits of technology used for strategic purposes (Hitt and Brynjolfsson, 1996). There are no commonly accepted concepts to measure its proper value and no agreement as to which variables to measure (Ittner and Larcker, 2000). Furthermore, unlike financial measures, there is no common denominator and evaluating performance is difficult when some measures are denominated in time, some in quantities and others in arbitrary ways (Ittner and Larcker, 2000). Thus, while many authors stress the need to evaluate IT projects from a strategic perspective, few offer concrete suggestions as to how perform such evaluations, with the exception of using subjective judgement. Thus, evaluation in the context of information technology based systems is both complex and multi-faceted. There is little agreement as to how such evaluations should be carried out, and no commonly accepted range of techniques available to help hoteliers with their channel evaluation and assessment decisions. Furthermore, as has been discussed, there are deficiencies in the existing appraisal techniques. As a result, new business measures that ‘‘effectively represent digital commerce, determining the health and profitability of each channel available are needed’’ (Castleberry and Hempell, 1998). Collective wisdom now recommends a multidimensional methodology involving both qualitative and quantitative components, as if a broad range of factors—not just the technical costs and monetary benefits— are taken into account, the evaluation process is more likely to be valid (Avison and Horton, 1988). In any case the hotel sector has been poor at using formal techniques for information technology related investment appraisal (Cline, 1999). For example, the 1987 study by Whitaker (1987) revealed that less than half of hotel computer system installations were preceded by a formal systems analysis. In most cases, the decision process ‘‘consisted of a series of ad hoc and uncoordinated decisions based ARTICLE IN PRESS P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 185 on vague intentions’’. Murphy et al. (1996) found that ‘‘few businesses have based their Internet investment on anything more than a back-of-the-envelope calculation—18% have done no analysis at all, while only 12% have justified their investment under the scrutiny typically required within an organisation’’. Pringle (1995) makes the pointed observation that use of electronic channels by hotels may not, in many case be due to a carefully thought out strategy, but to external pressure—a case of everyone else is doing it so why don’t we? There is, however, some evidence that the major chains have started to evaluate their existing channels. Respondents to a limited survey (Smith David and Grabski, 1996) considered the impact of technology on productivity prior to investment. However, such consideration was unstructured as a result of the measurement difficulties discussed earlier and in any case investments often went ahead with any evidence that they would generate any improvements or productivity increase. 6. Research objectives and methodology As can be seen from the above discussion, literature regarding evaluation of electronic distribution channels of distribution is still sparse without any robust or accepted knowledge as to the process that should be followed and the criteria that should be used. However, with the increasing capital, organisational and technical requirements to successfully use an electronic channel, such assessments have become of critical concern to industry practitioners. Not all channels can be adopted and thus both those channels currently being used and any potential additions need to be evaluated to identify those that best match the needs of the organisation. Thus, the primary aims of this study were to establish and prioritise a portfolio of factors for use in the hotel electronic channel of distribution evaluation decision, both at the time of initial consideration and when ongoing use is being considered. As existing literature on hotel electronic distribution was mainly descriptive there was little a priori research available to help frame the research study. This, coupled with the unstructured nature of the research problem, prompted the use of qualitative research—specifically a grounded theory approach and the Delphi Technique, as a foundation for an informed quantitative investigation. A three-round Delphi study using experts in the field of hotel electronic distribution was thus used to develop, validate and prioritise a baseline list of potential evaluation criteria. The Delphi process itself has been well documented; a panel of participants is chosen to give their opinions on the subject under investigation. Each is guaranteed anonymity in terms of their responses; neither meets nor corresponds with other panel members; answers questions provided by the facilitator; and are normally given at least one opportunity to re-evaluate their answers based upon examination of the group response. In this study, the expert panel was selected by identifying speakers on technology related topics at major hospitality industry conferences in 30 months prior to the study. Based on the events calendars of two major academic journals, the programmes of 105 conferences were analysed, giving a potential pool of over 600 speakers. Those who had three or more presentations at separate ARTICLE IN PRESS 186 P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 conferences were invited to participate in the study. Potential respondents were asked to evaluate their own level of expertise (Loveridge and Georghiou, 1999). Of those invited, a total of 42 ‘‘experts’’ were willing and qualified to participate in the study. These were classified into five categories: Academic, Consultant, Hotelier, Researcher and System Supplier for comparison purposes, although subsequent analysis revealed no significant differences between the opinions of each group. Email was used as the communications medium throughout, and an overall response rate of 65% was achieved. 7. Channel adoption factors Initially the panel was asked to suggest the factors that should be taken into account when evaluating the use of a hotel electronic channel of distribution for the first time. A large number of factors were suggested in response, which were grouped into six broad categories using content analysis techniques. Of these, financial factors (focused on the cost or revenue aspects of using a channel) were the most commonly cited. Specific criteria mention included the overall cost of using the channel, transaction costs, set-up costs and the increased volume of transactions and revenue that could potentially be generated. However, few respondents explicitly combined these factors together by balancing costs against benefits or identifying the effect on profitability. Marketing factors were also frequently cited. These included the potential to service existing markets and the ability to address new customers in terms of market segment and geographical spread. Issues that focused on the strategic/tactical running of the firm were grouped into the management category. These included the effect that using the channel would have on the ‘‘brand image’’ of the hotel, competitive positioning and the effect on existing customer and distribution channel relationships. Operational factors included technical easy of use, integration with existing inventory databases, automation, control issues and reporting issues. System provider issues were the next most frequently cited category, and these included the reputation of the company providing the service, with their level of independence and level of understanding of the hotel sector also mentioned. Lastly, technical issues were the least frequently cited category. Both transaction speed and update speed were mentioned, as were data quality and security. The range and variety of criteria suggested by the initial Delphi round demonstrates the complexity of the adoption decision. However, the pattern of suggestions implies that evaluating the adoption of a channel is similar to most business decisions and should be based on cost and markets served. How the channel operates, and the technology behind it, should not be of prime concern. Such a viewpoint is supported by the content analysis, which revealed far more cohesion in the responses to the financial and marketing categories. However, it is also clear that evaluation should be multi-faceted, and should not be undertaken using financial and marketing criteria alone. A broader model is needed—one that effectively combines the more important factors from each category to help generate the most appropriate decision. ARTICLE IN PRESS P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 187 8. Relative importance of adoption factors Although some conclusions could be drawn from frequency of citation, the list of criteria developed in the initial Delphi round needed to be prioritised to identify the most relevant evaluation factors. Thus they were fed back to the expert group, with each respondent requested, in addition to identifying any errors, omissions and duplications, to rate each factor using a five point continuous rating scale, from ‘‘1’’ meaning that the factor could be ignored to ‘‘5’’ meaning that consideration of the factor was essential. While the initial round had suggested that channels should primarily be evaluated on financial and marketing grounds, with (in descending order) strategic, operational, system provider and technical issues also being taken into account, as can be seen from Table 1, the importance rating identified a different set of priorities. Technical factors in particular were rated as being the most essential to take into consideration in the adoption decision. Similarly, the majority of the operational and system provider issues also rated highly. In contrast, financial factors (with the exception, unsurprisingly, of ‘‘initial capital cost’’) were rated as being least important. The converse pattern continued in relation to both marketing and strategic issues, both of which were frequently cited in the initial round but received relatively low importance scores. Such findings contrast with the priorities identified in contemporary evaluation literature, where, as has been discussed, most authors focus on financial techniques or strategic analysis criteria as evaluation methods. The findings suggest that a much broader range of factors, and in particular, a large number of operational issues, need to be considered. A possible explanation may be that while a wide range of issues should potentially be taken into consideration when evaluating an electronic channel (reflected in the large number of suggestions for possible factors received in the initial round), it is how the system will perform in practice that should be the key deciding factor in its adoption—hence the emphasis on technical and operational factors when asked to rate their importance. However, it should also be pointed out that the majority of the issues were rated as being important. If the scale mid-point was used as a cut-off point, only five factors would be eliminated—four of which would be financial! The overall score level, coupled with the lack of suggestions for factors that should be added or removed, indicates that the correct set of evaluation factors for the adoption of hotel electronic distribution systems has been identified. However, the relatively consistent scores make it difficult to distinguish the more important decision factors. Thus an alternative ranking method was used in the final round to validate and prioritise the factors. 9. Validating the adoption factors As the second round results were substantially different to what had been anticipated, a revalidation of the findings was necessary. Panel members were presented with a summary of the second round findings, along with a questionnaire 188 Factor Delphi round one importance rating (1=ignore to 5=essential) Delphi round two importance ranking Technical System Manage- Opera- Market- Finan- N Provider ment tional ing cial Mean Standard deviation 23 4.22 0.80 0.427 41 4 23 4.17 0.78 0.324 26 9 23 4.09 0.79 0.162 33 7 24 23 23 4.08 4.04 4.00 1.02 1.02 1.09 0.718 0.654 1.162 38 27 38 5 8 5 24 4.00 1.06 1.184 25 10 23 4.00 0.90 0.807 46 1 23 3.96 0.98 1.192 46 1 24 3.92 0.97 0.437 25 10 24 3.75 1.15 0.210 24 12 23 3.74 0.96 0.089 21 13 Skew Votes Adoption ranking ARTICLE IN PRESS Speed at which transaction can be completed Speed at which information and rates can be updated Reputation of the provider of the channel Initial capital cost Security of the channel Traffic levels (number of visitors, lookers, hits) Integration with existing electronic channels from a data maintenance perspective Operational ease of use from the hotel’s perspective Potential of channel to open up new market segments Effect on existing customer relationships Effect of using channel on brand image Transaction cost Content analysis category P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 Table 1 Channel evaluation–adoption factors 3.70 1.33 0.654 46 1 23 23 3.57 3.57 1.16 1.34 0.555 0.584 9 8 18 19 24 3.54 1.28 0.369 12 15 24 3.46 0.98 0.483 1 22 24 24 3.42 3.29 1.25 1.30 0.452 0.079 11 14 16 14 24 3.25 1.33 0.259 2 21 23 24 2.96 2.96 1.30 1.33 0.324 0.322 — 1 — 22 24 24 23 2.96 2.57 2.57 1.43 1.48 1.25 0.177 0.146 0.570 7 — 11 20 — 16 ARTICLE IN PRESS 23 P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 Potential of channel to address current market segments Joining or introduction fee Presence of competitors in the channel under consideration Capability to provide management information Effect on existing channel’s of distribution Effect on room rate Ability to individually recognize customers Availability of alternative electronic channels Achieved volume of transactions Independence of the provider of the channel Forecast revenue from channel Achieved revenue from channel Forecast volume of transactions 189 ARTICLE IN PRESS 190 P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 showing the mean importance score for each factor. Following the Delphi methodology, instructions were included informing them that they could either take the group’s mean importance score into account in their revised response, or ignore it, depending on the strength of their own expert opinion. Panel members were then asked to rank the factors they felt were most important using a voting system that forced prioritisation. Each was given a limited number of votes to assign to those factors thought most important. The results (see Table 1) reconfirm the theory developed earlier—in the opinion of the expert panel; operation and technical issues should be at the forefront of evaluation factors when adopting a hotel electronic channel of distribution. As in prior rounds, a single factor from each of the other categories also was felt to be of priority. In the financial category, ‘‘Initial capital cost’’ received the highest number of votes, in marketing factors ‘‘Potential to open up new market segments’’, and in the system provider group, ‘‘reputation of the system provider’’ all received high relative rankings. Thus, the final round validated earlier findings and identified the most important factors to take into account in the adoption evaluation decision. While these include certain financial and marketing concepts, it can be seen that, in contrast to established theory, a wider range of factors, focusing mainly on the way in which the channel will perform in operation, need to be considered. 10. Developing a list of potential continuation factors While the evaluation process might be similar, it is possible that a different set of criteria might be important when evaluating the continued use of an electronic distribution channel. An identical methodology was used to investigate this issue with Delphi panellists initially asked to nominate the factors they felt should be taken into account in such a scenario. The majority of respondents indicated that the process was essentially the same, but most also chose to nominate additional factors, which when analysed revealed that the continuation decision should be greatly influenced by the actual performance of the system. As with adoption factors, respondents were subsequently asked to rate the factors identified in terms of their importance. An identical rating scale was used, and the results are shown in Table 2. Once again, technical and operational issues are rated highest, although the pattern in this case is less clear as a variety of other issues also score highly. Financial issues once again score poorly, with initial capital cost and joining fees understandably receive the lowest scores as they are in effect sunk costs and thus less relevant to the decision as to whether to continue using a channel. However in contrast to with the adoption scenario, revenue related factors achieve relatively high mean scores, as did transaction cost, supporting the theory suggesting by the first round—that it is day-to-day performance, rather than abstract financial models or strategic issues, that should determine whether to continue using a channel. As with adoption factors, such a viewpoint was in opposition to that commonly recommended in published literature, and thus it was revalidated in the final round of the study. Table 2 Channel evaluation–continuation factors Factor Content analysis category Mean Standard deviation Votes Speed at which information and rates can be updated Speed at which transaction can be completed Ability to individually recognise customers Potential of channel to open up new market segments Transaction cost Operational ease of use from the hotel’s perspective Traffic levels (number of visitors, lookers, hits) Security of the channel Potential of channel to address current market segments Capability to provide management information Achieved volume of transactions 23 4.52 0.59 0.806 28 8 23 4.43 0.66 0.767 34 4 24 4.38 1.06 2.061 31 6 23 4.30 0.82 0.647 40 1 23 23 4.26 4.26 0.92 1.01 0.573 38 1.739 34 2 4 23 4.17 1.15 1.535 19 14 23 23 4.13 4.13 0.97 0.87 0.610 28 0.269 29 8 7 24 4.12 1.08 1.182 23 13 23 4.09 1.16 1.697 26 10 System Manage- Opera- MarketProvider ment tional ing Financial Skew Ongoing ranking ARTICLE IN PRESS N Technical 191 Delphi round two importance ranking P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 Delphi round one importance rating (1=ignore to 5=essential) 192 Table 2 (continued) Factor Content analysis category Financial N Mean Standard deviation Votes 24 4.08 1.10 1.246 25 11 24 4.08 1.14 1.139 24 12 24 4.04 1.37 1.419 38 2 24 3.87 1.12 0.349 12 15 23 3.78 0.95 0.218 8 18 24 23 3.63 3.61 1.10 1.12 0.456 0.191 8 8 18 18 23 3.57 1.24 0.321 9 16 24 3.54 1.02 0.011 3 21 24 3.54 1.28 0.503 9 16 24 3.17 1.34 0.094 2 23 24 3.08 1.28 0.102 3 21 24 23 2.92 2.87 1.47 1.55 0.245 0.157 2 1 23 25 Skew Ongoing ranking ARTICLE IN PRESS Integration with existing channels from a data maintenance perspective Effect on existing customer relationships Achieved revenue from channel Effect of using channel on brand image Reputation of the provider of the channel Effect on room rate Forecast volume of transactions Presence of competitors in the channel under consideration Effect on existing channel’s of distribution Forecast revenue from channel Availability of alternative electronic channels Independence of the provider of the channel Initial capital cost Joining or introduction fee System Manage- Opera- MarketProvider ment tional ing Delphi round two importance ranking P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 Technical Delphi round one importance rating (1=ignore to 5=essential) ARTICLE IN PRESS P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 193 11. Revalidating the continuation factors As was the case with adoption factors, panel members were given an explicit number of votes and asked to prioritise the factors that should be taken into account when evaluating the continued use of a channel. The validation process confirmed earlier findings; although the highest scoring factor (‘‘potential to open up new market segments’’) was marketing oriented, operational issues such as ‘‘transaction speed’’ and ‘‘ease of use’’ ‘‘speed’’ and ‘‘security’’ followed close behind. Similarly, financial factors were confirmed as being more important than in the adoption evaluation decision, with both ‘‘transaction cost’’ and ‘‘achieved revenue from the channel’’ receiving a high number of votes. However, unlike with the discussion of the adoption factors, the pattern of what is important is not as clear, incorporating financial, marketing, management, technical and operational issues. Overall, a wider range of issues needs to be considered, but as can be seen from Table 2, the majority of these focus on the actual performance of the channel. 12. Adoption factors versus continuation factors Although the evaluation decision is similar, the Delphi panel clearly identified a different set of factors as being more important when an electronic distribution channel is initially being considered versus when its ongoing use is being assessed. A paired sample t-test (see Table 3) highlights these differences. In four of these factors (‘‘initial capital cost’’, ‘‘joining or introduction fee’’, ‘‘achieved revenue from channel’’ and ‘‘achieved volume of transactions’’) differences were to be expected as they relate primarily to just one scenario. Similarly, the difference in the scores for ‘‘transaction cost’’ was predictable, as, while this issue is important in the adoption decision, it becomes more important when the system is in actual use and its effect is actually being experienced. The results for four other factors were also found to be statistically different. Mean scores for ‘‘Speed at which information and rates can be updated’’, ‘‘Capability to provide management information’’ and ‘‘Ability to individually recognise customers’’ were all significantly higher for the continued use evaluation decision, adding to the evidence that actual performance becomes more important in this scenario. Lastly, the scores for ‘‘Forecasted volume of transactions’’ were also significantly lower in the adoption scenario, once again confirming that it is how the system will operate, rather than its performance that should be of prime consideration when evaluating a system’s adoption. An alternative method of analysis is to use a matrix to demonstrate the factors that should be taken into account in each (and both) scenarios. By plotting the adoption importance scores against those for continuation it is possible to identify the factors most important in each scenario, as well as to visualise their relative importance (see Fig. 1). Those shown above the horizontal axis are important than average in the channel adoption decision, while those to the right of the vertical axis are more important than average when the continued use of a channel is being evaluated. Factors listed in the top right-hand quadrant are important in both ARTICLE IN PRESS 194 P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 Table 3 Paired sample t-test comparing mean importance scores for adoption and continuation factors Factor Category Ability to individually recognise customers Achieved revenue from channel Achieved volume of transactions Availability of alternative electronic channels Capability to provide management information Effect of using channel on brand image Effect on existing channel’s of distribution Effect on existing customer relationships Effect on room rate Forecast revenue from channel Forecast volume of transactions Independence of the provider of the channel Initial capital cost Integration with existing electronic channels Joining or introduction fee Ease of use from the hotel’s perspective Potential of channel to address current market segments Potential of channel to open up new market segments Presence of competitors in the channel under consideration Reputation of the provider of the channel Security of the channel Speed at which information and rates can be updated Speed at which transaction can be completed Traffic levels (number of visitors, lookers, hits) Transaction cost Management * t df Sig (2tailed) 4.511 23 0.000 Financial Financial Management 3.844 3.861 0.401 23 22 23 0.001 0.001 0.692 Operational 3.245 23 0.004 Marketing Management 0.647 0.358 23 23 0.524 0.723 Marketing Financial Financial Financial System Provider 0.678 1.045 1.857 2.405 0.157 23 23 23 22 23 0.504 0.307 0.076 0.025 0.877 Financial Operational 3.685 0.440 23 23 0.001 0.664 Financial Operational Marketing 2.113 1.298 2.011 22 22 22 0.046 0.208 0.057 Marketing 1.558 22 0.133 Marketing 0.000 22 1.000 System Provider 1.775 22 0.090 Technical Technical 0.492 2.336 22 22 0.628 0.029 Technical 1.226 22 0.233 Technical 1.164 22 0.257 Financial 2.228 22 0.036 p-value o0.05. situations, and thus can be regarded as being of key importance. From the matrix, it is immediately noticeable that the majority of the factors in this quadrant are operational or technical, together with a small number of marketing factors. ‘‘Ease of use’’, ‘‘Integration with existing inventory databases’’, ‘‘Transaction speed’’, ‘‘Update speed’’ and ‘‘Security’’ all score highly in both scenarios. A marketing ARTICLE IN PRESS P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 195 Fig. 1. Matrix analysis of evaluation factors. factor—‘‘the potential of a channel to open up new market segments’’—scores highest overall, perhaps indicating that respondents perceive one of the key roles of electronic distribution channels as being the generation of incremental business. That being said, this sector also contains two other marketing factors—‘‘the potential of a channel to address current market segments’’ and ‘‘effect on existing customer relationships’’—indicating that in addition to generating new business, a channel should also be able to service existing customers effectively. The only financial factor in this segment is transaction cost, which, while high on the continued use axis, is low on the adoption axis, suggesting that the level of cost associated with each transaction is more relevant while the channel is being used rather than when its adoption is being assessed. The bottom left hand quadrant (less important in both scenarios) include the majority of the financial factors, including ‘‘Joining fee’’, ‘‘Forecasted Transaction Volume’’, ‘‘Forecasted Revenue’’ and ‘‘Effect on Room Rate’’. Furthermore, two of the more strategic issues—‘‘Availability of alternative ARTICLE IN PRESS 196 P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 electronic channels’’ and ‘‘Effect on existing channels of distribution’’ are here also and are among the lowest on both scales, indicating that in contrast to the theories cited in the literature, respondents feel that economic and strategic issues are not the ones that should be at the forefront of the decision factors when evaluating the use of an electronic channel of distribution. In addition to the common factors discussed above, the matrix also helps to identify those issues most important in each of the alternative scenarios. Not surprisingly, ‘‘Initial Capital Cost’’ is regarded as being important when evaluating the adoption of a channel, but less so in terms of evaluating its continued use. Instead, factors such as achieved volumes of transaction and achieved revenues come to the forefront. Thus, the analysis shows that the panel perceives the key issues to be different when evaluation hotel electronic channels of distribution for adoption and for continued use. While there is some overlap—i.e. those thought to be important in both situations—a different set of additional factors becomes important in the two scenarios. In terms of adopting a channel, the matrix shows that factors such as ‘‘initial capital cost’’, ‘‘traffic levels’’ and ‘‘reputation of the system provider’’ are the ones that need to be considered. In contrast, once the channel has been adopted, factors focusing on the revenue side of the profitability equation should be taken into account. While there is some common ground, the evaluation process in the two situations is clearly very different. 13. Conclusions This paper has presented the results of a three-round Delphi study focused on identifying and prioritising a portfolio of evaluation factors for use in evaluating hotel electronic channels of distribution. Although the findings must be regarded as indicative (Babbie, 1995), they do provide a useful set of criteria for consideration in the channel evaluation process. It is clear that a different set of factors is considered more relevant depending on whether the initial adoption of a channel or its continuation is being evaluated. For adoption, operational and technical issues such as ease of use, transaction speed, update speed, traffic levels, integration and security were found to be the primary factors that should be taken into consideration. Initial capital cost also needs to be considered, as does the channel’s ability to service both existing and additional market segments. However, it is clear that it is the system methods of operation— rather than how it will perform financially or contribute strategically—that are thought to be of prime consideration in the channel adoption decision. In contrast, the continuation decision appears to be more complex. Not only were more criteria suggested in this scenario, but also the pattern of importance scores is less clear. The decision seems to be multifaceted, incorporating financial, marketing, strategic, operational and technical elements. Technical and operational issues remain important, but financial aspects (particularly those on the revenue side of the equation) were found to be more important than in the adoption evaluation decision, suggesting that it is the channel’s actual performance in practice that should be the ARTICLE IN PRESS P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 197 Table 4 Summary ranking of key evaluation factors Factor Category Importance ranking Adoption Continuation Potential of the channel to open up new market segments Ease of use from the hotel’s perspective Potential of the channel to address current market segments Speed at which transaction can be completed Security Speed at which information/rates can be updated Achieved revenue from channel Transaction cost Traffic levels Initial capital cost Ability to recognise individual customers Reputation of the system provider Integration from a data maintenance perspective Achieved volume of transactions Marketing 1 Operational 1 Marketing 1 Technical 4 Technical 8 Technical 9 Financial Financial Technical 5 Financial 5 Management System Provider 7 Operational 10 Financial 1 4 7 4 8 8 2 2 6 10 key determinant as to whether to continue to use it. A summary of the key factors is shown in Table 4, where those issues important to both adoption and continuation are presented first, followed by those that are important in one or the other situation, ordered in terms of their relative importance. References Anderson Consulting, 1998. The Future of Travel Distribution: Securing Loyalty in an Efficient Travel Market. Anderson Consulting, New York. Applegate, L., 1999. Making the Case for IT Investments. Financial Times Mastering Information Management, London. Applegate, L., McFarlan, F., et al., 1996. Corporate Information Systems Management: The Issues Facing Senior Executives. Irwin, Chicago. Avison, D., Horton, J., 1988. Evaluation and information system development. In: Avison, D., Fitzgerald, G., Bjorn Andersen, N., et al. (Eds.), Investimenti in Information Technology nel settore bancario. FrancoAngeli, Florence. Babbie, E., 1995. The Practice of Social Research. Wadsworth Publishing, Belmount, CA. Ballantine, J., Stray, S., 1999. Information systems and other capital investments: evaluation practices compared. Logistics Information Management 12 (1/2), 78–93. Banker, R., Kauffman, R., et al., 1993. Information technology, strategy and firm performance: new perspectives for senior management from information systems research. In: Banker, R., Kauffman, R., Mahmood, M. (Eds.), Strategic Information Technology Management: Perspectives on Organisational Growth and Competitive Advantage. Idea Group Publishing, Harrisburg, PA. Bennett, M., 1993. Information technology and travel agency—a customer service perspective. Tourism Management 14 (4), 259–266. Brady, M., Saren, M., et al., 1999. The impact of it on marketing: an evaluation. Management Decision 37 (10), 758–766. ARTICLE IN PRESS 198 P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 Castleberry, J., Hempell, C., et al., 1998. Electronic shelf space on the global distribution network. Hospitality and Leisure Executive Report 5, 19–24. Clemons, E., Weber, B., 1990. Making the information technology investment decison: A principal approach. In: Sprague, R. (Ed.), Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences: Emerging Technologies and Applications: Track IV. IEEE Computer Society Press, Los Almos, CA, pp. 147–156. Cline, R., 1999. Brand marketing in the hospitality industry—art or science. HSMAI Gazette (1/99), pp. 6–7, 14. Connolly, D., 1999. Understanding Information Technology Investment Decision Making in the Context of Hotel Global Distribution Systems: A Multiple-Case Study. Hotel and Tourism Management. Blacksburg, Virginia. Connolly, D., Olsen, M., et al., 2000. The Hospitality Industry and the Digital Economy: An Executive Summary of Key Technology Trends Surfaced at the Lausanne Think Tank. International Hotel and Restaurant Association, Paris. Coyne, R., 1995. The reservations revolution. Hotel & Motel Management, 24 July 1995, 54–57. Crichton, E., Edgar, D., 1995. Managing complexity for competitive advantage: an it perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 7 (2/3), 12–18. Dev, C., Olsen, M., 1998. Marketing in the New Millennium—Findings of the IH&RA Think-Tank on Marketing. International Hotel & Restaurant Association, Paris. Go, F., Pine, R., 1995. Globalization Strategy in the Hotel Industry. Routledge, New York. Griffin, R., 1997. Evaluating the success of Lodging Yeild Management Systems. FIU Hospitality Review 15 (1), 57–71. Hitt, L., Brynjolfsson, E., 1996. Productivity, business profitability and consumer surplus: three different measures of information technology value. MIS Quarterly 20 (2), 121–143. Hopwood, A.G., 1983. Evaluating the Real Benefits. In: Otway, H.J., Peltu, M. (Eds.), New Office Technologies: Human and Organisational Aspects. Frances Pinter, London, pp. 37–50. Ittner, C., Larcker, D., 2000. Non-financial Performance Measures: What Works and What Doesn’t. Financial Times Mastering Management Series, London. Knowles, T., Garland, M., 1994. The strategic importance of CRSs in the airline industry. EIU Travel and Tourism Analyst 4, 4–6. Lefley, F., 1996. Strategic methodologies of investment appraisal of AMT projects: a review and synthesis. The Engineering Economics 41 (4), 345–363. Leonard, K., Mercer, K., 2000. A framework for information systems evaluation: the case of an integrated community-based health services delivery system. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurancet 13(2), vii–xiv. Lewis, R., Chambers, R., et al., 1995. Marketing Leadership in Hospitality. Van Nostrad Reinhold, New York. Loveridge, D., Georghiou, L., et al., 1999. United Kingdom Technology Foresight Programme. Manchester, Office of Science and Technology, University of Manchester. McFarlan, F., 1984. Information technology changes the way you compete. Harvard Business Review 62 (3), 98–103. Middleton, V., Clarke, J., 2001. Marketing in Travel and Tourism. Butterworth Heinemann, London. Murphy, J., Forrest, E., et al., 1996. Hotel management and marketing on the internet. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 37 (3), 70–82. Negroponte, N., 1995. Being Digital. Vintage Books, New York. O’Brien, T., 1997. Redefining IT value: novel approaches help determine the right spending levels. Information Week, April 7, pp. 71–72, 76. O’Connor, P., 1999. Electronic Information Distribution in Tourism and Hospitality. CAB International, London. O’Connor, P., 2002. The Changing Face of Destination Management Systems. EIU Travel & Tourism Analyst 5. Olsen, M., Zhoa, J.L., 1997. New management practices in the international hotel industry. Travel & Tourism Analyst 1, 53–75. ARTICLE IN PRESS P. O’Connor, A.J. Frew / Hospitality Management 23 (2004) 179–199 199 Poon, A., 1994. The new tourism revolution. Tourism Management 15 (2), 91–91. Pringle, S., 1995. International Reservations Systems—Their Strategic and Operational Objectives for the UK Hotel Industry. Napier University, Edinburgh. Remenyi, D., Sherwood-Smith, M., 1999. Maximise information systems value by continuous participative evaluation. Logistics Information Management 12 (1/2), 14–31. Smith David, J., Grabski, S., et al., 1996. The productivity paradox of hotel industry technology. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 37 (2), 64–70. Symons, V., 1991. A review of information systems evaluation: content, context and process. European Journal of Information Systems 1 (3), 205–212. Tapscott, D., 1996. The Digital Economy: Promise and Peril in the Age of Networked Intelligence. McGraw-Hill, New York. Vialle, O., 1995. Les GDS dans L’industrie Touristique. Organisation Mondiale de Tourisme (World Tourism Organisation), Madrid. Weill, P., 1991. The information technology payoff: implications for investment appraisal. Australian Accounting Review 2, 11. Whitaker, M., 1987. Overcoming the barriers to successful implementation of information technology in the UK hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management 6 (4), 229–235. WTO, 1991. Tourism to the Year 2000. World Tourism Organisation, Madrid.

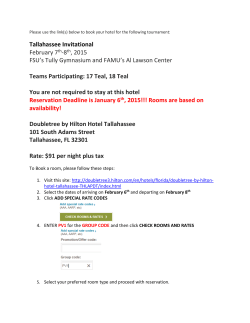

© Copyright 2026