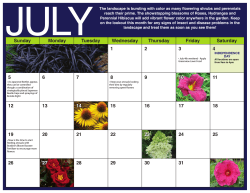

Body/Landscape Journals