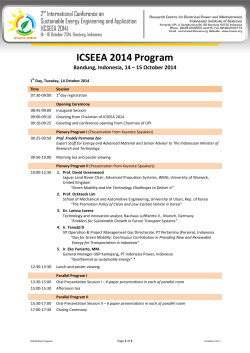

05_Dr.Claudio - Southeast Asian Studies