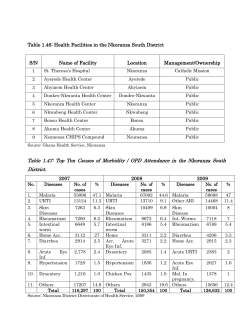

A pilot test a methodology for rapidly assessment of mosquito net use in the Kassena Nankana District, Northern Ghana.