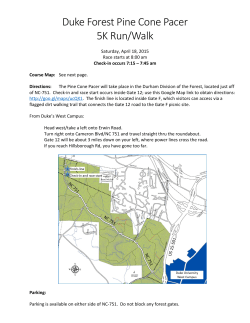

Spring 2015 - UBC Faculty of Forestry