ROunDTAbLE | InDIA - Piramal Fund Management Pvt. Ltd.

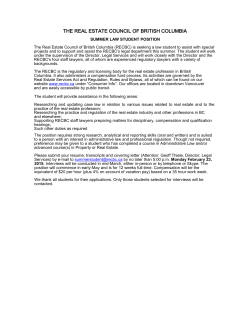

Roundtable | India Photography by Gautam Singh (L to R) Subhash Bedi, Subramanian Sriniwasan, Khushru Jijina and Rajesh Jaggi Of lions and tigers India’s private real estate market has been capital starved since a first wave of institutional investors in the market found little success. PERE hears from four surviving firms keen to ensure returning investors don’t suffer a similar fate. By Michelle Phillips Roundtable | India T he monsoon rain and high tide are a deadly combination in Mumbai. All around the distinctive One Indiabulls Center office building where PERE is holding its inaugural India roundtable discussion, rain pounds the windows and major roads flood. Somehow, all four participants have managed to find their way here. Each is glad to be in a dry place. Despite the depressing weather, the roundtable is in good voice. We have Kotak Realty Fund chief executive Subramanian Sriniwasan, Everstone Capital real estate managing partner Rajesh Jaggi, Red Fort Capital managing director Subhash Bedi, and Indiareit Fund Advisors managing director Khushru Jijina. Perhaps because they are old acquaintances, they quickly find comfort in one another’s company. Over the course of the two-hour discussion it becomes evident they also share similar thoughts on how to operate in India’s private real estate market today. Between 2005 and 2008, almost $14 billion was invested in the country’s bricks and mortar, according to data provider Venture Intelligence. Enchanted by India’s growth story, institution after institution committed capital and often to loosely defined strategies. But when they yielded scant success, the Indian property market’s place in the institutional investment portfolio largely became marginalized, particularly by nondomestic sources of capital. In response, these roundtablers are quick to agree the future resides in demonstrating a clearer focus. Out go broad, allencompassing strategies. Instead a distinctive, strictly-defined game plan is the tonic they believe will induce at least certain investors to return to these shores. They cannot guarantee 22 PERE | THE INDIA REPORT 2013 mistakes will not be repeated. But these men claim the firms which have survived are now hands-on in approach and hyperfocused in strategy. Stampede in, stampede out Each roundtabler has operated through 2005 to 2008, when 30 percent IRR expectations were common; and to a greater or lesser extent, each has the scars from what happened next. “I think in many ways, 2005 to 2008 was really about venture capital investment in real estate,” Sriniwasan says. Most institutions came to India with little or no experience of the country’s real estate, and committed large sums of money to managers and developers, who were equally in the dark about institutional expectations, he says. According to PERE’s Research and Analytics Division, almost $24 billion was raised in India for private equity real estate funds between 2005 and 2008, more than quadruple what has been raised since. As Jijina sees things, Indian managers were unaccustomed then to handling such large amounts of capital. “They had to set up with developers who were actually doing smaller projects, and suddenly these developers were bombarded with liquidity,” Jijina explains. Participants agreed that fund managers and developers alike had taken on more capital than they could handle. When $12 billion of foreign direct investment chased about $3 billion worth of equity deals in India’s top five cities, mistakes were bound to happen, Sriniwasan declares. Replete with resources, there was less emphasis then on tight investment parameters and mandates would include everything from residential to office to logistics, Sriniwasan says. Ji- jina chimes in by describing “non-understanding” institutional investors marrying with developers who were unacquainted with working with private equity. “In those days, most developers didn’t know the difference between an SPV and an SUV,” Sriniwasan responds, half-joking. The years immediately following the start of the global financial crisis in 2008 were dark days indeed (see inflation and GDP growth chart). Investors who had “lost their shirt” from their forays stampeded out of Indian real estate as quickly as they had stampeded in. In the course of just a year, roundtablers recall watching foreign capital dry up. The market’s reputation took a battering in the process. This is where Bedi chimes in: “The perception of India was built by the LPs that invested in 2005 to 2008, [and] their voices overshadow the one in 10 that stayed with it,” he says. “The people who put out money then were still on the fence licking their wounds as recently as a couple of years ago. They’re now getting to a stage where they can acknowledge that mistakes were made in terms of the managers or strategies or whatever. They are ready to move on.” A beautiful thing Since the crisis started, managers still ambitious to succeed in India claim to have learned too. The lesson for them, they confide, was in finding a focused strategy that is as robust as it is attractive. It must be easily explained to investors too. For Everstone that meant tightening the remit to funds focused purely on logistics real estate. Red Fort meanwhile has kept its focus predominantly on the residential market. “Strategies today are far more sharply focused than five years ago, when pretty much everybody wanted to do everything,” Sriniwasan says. “It’s only now that you get ‘real’ real estate investments, because people have gone through the cycles, people have learned from their mistakes. There are survivors and then there are people who decided to leave the industry. That leaves you with a consolidated industry and very few managers.” Those that have survived have done so because they have adopted clearly defined and often limited strategies, PERE hears. And that is playing into the hands of institutional investors as they seek to cement long-term positions. “The market is a beautiful thing: it’s weeded out people who know what they’re doing and those that do not,” Bedi points out. “And so once a person decides to re-look at India, it’s actually much easier to underwrite the manager, strategy, track record, and then to put capital to work.” While distinct strategies are top of the agenda, also important these days is for real estate investment managers to be able to demonstrate operational expertise. The ability to source a development is today as attractive, if not more, as sourcing a developer with which to partner. The same applies to developers too when it comes to attracting private equity partners. “The number of developers who will receive capital has shrunk significantly, so it’s easy for Subhash or myself or any of these guys to look at the paper and say, ‘might be a great project, but this developer? Not doing it,’” Sriniwasan says. Investing then gets even harder as the good developers become cognizant of their increasingly attractive position, Jaggi adds. The participants Subramanian Sriniwasan Chief executive officer, Kotak Realty Fund Director, Kotak Investment Advisors Sriniwasan joined the Kotak Mahindra group in 1993, working in its investment banking joint venture with Goldman Sachs until 2005. Now serving as the chief executive of Kotak Realty Fund and the founder of Kotak Mahindra’s real estate fund management business, he raised the firm’s first $100 million fund in 2005. Under his leadership Kotak Realty has scaled up to over $1 billion assets under management. Rajesh Jaggi Managing partner, real estate Everstone Capital With over 14 years of real estate experience in India, Jaggi is responsible for all facets of Everstone’s real estate investments and operations. Prior to Everstone, he was the managing director of Peninsula Land, a $250 million listed Indian real estate company. Everstone has about $2 billion under management and has developed 33 million square feet of retail, residential, commercial and industrial real estate projects across 16 Indian cities. Subhash Bedi Managing director Red Fort Capital One of the founders of the $1 billion Indian real estate fund manager, Bedi has led or closed about $1 billion of Indian real estate transactions. Before starting Red Fort in 2007, he held the position of partner at advisory firms Krista International and American Capital Realty. Khushru Jijina Managing director Indiareit Fund Advisors With over 2 decades of experience in real estate, corporate finance and treasury management, Jijina was one of the key founders of Indiareit in 2005. He played a key role in raising the firm’s two domestic funds (totaling INR1,014 crores) and the $200 million Offshore Fund, as well as in deploying that capital. The firm currently has INR43 billion under management. THE INDIA REPORT 2013 | PERE 23 Roundtable | India Of course, this emphasis on operational expertise can provoke certain investors to miss out the investment manager altogether in favor of working directly with the lions within the developer fraternity. “Developers also know that they are being chased by private equity money,” Jaggi adds. That is why, the table agrees, it is important nowadays for the manager to demonstrate its development credentials, whether to work better alongside developers or, in some instances, replace them altogether. Hands on, cash out Bedi points out that by focusing their strategies on logistics and residential respectively, Everstone and Red Fort have made themselves into fund managers cum developers. Further, an allocator-only approach of throwing capital at developers from a corporate tower and expecting quarterly interest payments is “doomed to fail,” he claims. “That’s what happened in 2006: you don’t just show up at a quarterly board meeting and expect your money back.” Each of today’s participants can share anecdotes of peers doing that with negative outcomes. “So all of us have strong operational teams involved in these projects,” says Bedi, motioning to everyone around the table. “Because at the end of the day, the developer’s going to give your money back if he’s making money.” The Red Fort executive says to that end his firm employs staff with development expertise to ensure a strong outcome. However adept a firm’s development expertise becomes working with bona fide developers will remain a reality. Jaggi The big picture Inflation (CPI) GDP growth rate 14% 12% 12% 10% 10% 8% 8% 6% 6% 4% 4% 2% 2% 0% 2013 (to date) 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 0% 2013 (projected) 2012 2011 2010 2009 2008 2007 Indian inflation has been hard to curtail since the global financial crisis started while the country’s growth has also taken a battering in recent years Source: Inflation.eu; World Bank 24 PERE | THE INDIA REPORT 2013 2006 International assumptions The roundtable underlines the feeling that operating as a fund manager and a developer concurrently can be challenging, particularly when you consider India’s real estate investment proposition predominantly centers on development. One major challenge is staying abreast of local movements in the market and government regulation. Since most regions of India are subject as much to localized forces as countrywide forces, adding value in one area of the country might have little in common with adding value in another. Jijina says: “People ask me what the prices are in Mumbai now. Are they going down? You can’t generalize. It can be central Mumbai versus the eastern or western suburbs. These markets do not perform uniformly.” He admits this can be frustrating for new entrants to the market as they apply experiences gleaned from other corners of the globe to India’s property markets. International investment assumptions are of little help in India, Sriniwasan continues. While an investor might balk at the proposition of say, a township that is completely sold out even though the road to it still is not built – he has offered tractor rides for site visits on occasion – the development mentality in the country is such that these schemes often still work. “These guys are saying: ‘what’s going on in this country? There’s no road here, but everything is sold,” he explains. The roundtablers admit the idea of needing “local expertise” in real estate has been rehashed beyond cliché. However, such Exchange fate When it comes to arresting the decline in value of India’s rupee compared to international currencies, PERE’s India roundtable believes India’s central government has their backs. Real estate investment managers active in India perennially worry about rapidly changing local policies. That is unsurprising given India is a country comprising 29 states, each with largely independent economies. Nonetheless, at PERE’s India roundtable a central government issue is more pressing: the falling price of the rupee when compared to international currencies. The value of the rupee is understandably enough to keep many fund managers up at night, as it has fallen by about 50 percent since 2008. In 2013 alone, the currency’s valuation has fallen from INR54.8 per 1 US dollar to INR61. The table remarks that it has not seen fall in valuation like this since 1991. Kotak’s Sriniwasan says it has been eating into fund performance with some investors having lost 6 percent to 7 percent in value on the exchange rate alone. Sriniwasan, however, is not panicking because of commitments the government has made to prevent it from dropping too far below 60 rupees to the dollar. In 1991, to honor a similar commitment, the government actually guaranteed a buffer with its gold reserves, and Sriniwasan believes it is just as committed this time. “I’m not worried, because India always works when its back is against the wall, and it currently has its back to the wall,” he says. Currency trap USD/Rupee conversion last 5 years 65 Rupee per dollar reiterates the need for a hands-on approach in such situations. “We actually sit with the developer and go through the plans, we go through the costing, we go through everything. So it’s almost like we’re managing the show together.” Such micromanagement was rare between 2005 and 2008. Then, he recalls: “everyone just made investments on a spreadsheet.” The roundtable agrees unanimously the market is healthier for its better engagement with development partners. Further, investing in development via a fund manager like those present today offers a selection of possibilities in terms of what form the investment takes. Versus 2006, when investors had few options beyond taking equity positions in developments, Bedi says: “Today, you can do development as equity, you can do development as debt, you can actually invest in an NBFC [non-banking financial company] if you choose to do so, and you can buy yield-producing assets.” Playing the role of developer comes with a price for managers, however. For one, most managers cannot charge development fees in addition to management fees. While not a legal condition, Bedi says it would not be acceptable to institutional investors, given the high risk associated with deploying capital in what is still widely regarded as an immature property market.“Investors are happy to give development fees in much more mature markets to private equity fund managers,” he says. “I guarantee you, the Indian fund manager is doing triple what those funds do, but we can’t charge for it.” Despite begrudging the lack of fees, Bedi’s peers here today extol a certain prowess when describing their development capabilities. “We always say that we are real estate professionals first and fund managers second,” says Jijina. 60 55 50 45 40 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Rupees have fallen in value by 50 percent compared to the US dollar and that has trapped some of the first foreign investors in Indian real estate. Source: XE.com are the intricate nuances between one suburb and another, let alone one city and another, it unquestionably still carries weight. Jijina illustrates by touching on the processes of gaining planning permissions. Delhi’s system is different from Mumbai where the process can take up to two years. That implies potentially sticky situations for limited-life investment THE INDIA REPORT 2013 | PERE 25 Roundtable | India mandates that need to see returns quicker. To mitigate possible investment paralysis Jijina says his experience and the right connections have enabled him to push certain projects through the system in as little as six months. Jaggi believes the key to ensuring local expertise is by recruiting in markets in which the firm wants to transact. This roundtable won’t identify platforms which had “plopped” an international executive into a role that demanded local nous but said these platforms were burned because the executive could not grasp local practices effectively. This gives the table a reason to warn investors keen to shun third-party investment managers and tie-up with developers directly to reconsider. One recent tie-up came last summer when Dutch pension manager Algemene Pensioen Group (APG) partnered with Mumbai-listed developer Godrej Properties (see guest commentary, page 11) to form a residential development company, with an initial capital injection of INR770 crore (€109.5 million; $138 million). The JV firm has earmarked the next seven years for generating returns, and in the meantime APG has told PERE it is unlikely to commit to a fund structure in India. Though not referring directly to APG and Godrej, the managers of this roundtable say that while direct partnerships can work, especially for income-producing assets, development is an “entirely different animal” and investors doing it directly will need to commit plenty of resources to the effort, and not only capital. Sriniwasan’s Kotak is one firm that has managed to attract the capital of large institutional investors that would rather trust a third-party manager than wade into the market directly. While he could not divulge the firm’s capital raising activities, it was reported in the summer that Kotak has raised $200 million in seed capital for its latest offshore fund from sovereign wealth fund Abu Dhabi Investment Authority. Likewise, Everstone also held a $200 million first close in May for its $350 million JV logistics fund with capital commitments from around half a dozen US investors. And PERE has learned that Red Fort is poised to hold a first closing for its third opportunistic fund for which it wants $500 million. The members of this roundtable believe it is equipped to work with developers. “At the end of the day, I would say the toughest beast to tame in India is your [joint venture] partner,” Bedi says. “A lot of times people ask me, ‘Why are the Indian managers so cocky?’ Well, the ones that are left have to tame these lions.” He draws a distinction with “some classic Harvard business school turned New York investment banker” who, in his opinion, “would be eaten alive,” to explain why Indian real estate fund managers might have “strong personalities.” Long haulers “It’s been our experience that it takes time for a person to peel the onion on India,” Bedi explains. Consequently, it is of little surprise to this roundtable that it is the largest institutional investors that have returned to the market first as these typically have longer-term investment horizons. Accordingly, it is the prerogative of the managers present today to appeal to this source of capital with strategies that fit a lengthier tenure than before. 26 PERE | THE INDIA REPORT 2013 “When we’re talking to the LP world, we are actually wanting them to commit money for the longer time frame,” Jaggi says. The Indian real estate market also goes through very fast cycles, Jijina adds. A six-year project might pass through two complete cycles, he points out. As such, a poorly-timed entry or exit could derail its prospects. Bedi wades in: “Am I brilliant enough to pick the peaks in values? No. But I do know that the fundamentals of the middle class are there, so over a five or six-year project, it’s all going to even out.” It is little wonder then why certain investors have committed capital to evergreen investment structures that peg their fortunes to a longer time frame. But what does that mean for managers of limited life funds? Perhaps predictably, this group of managers still sees a place for closed-ended offerings. By Bedi’s reckoning a five-year fund is dangerously short but a fund life of between eight years and ten years is about the right gauge. Widely agreed is that the impatience for quick returns commonly associated with domestic capital makes it less appealing compared to the longer-term positions sought by international equity providers. There’s a feeling that the property investments of India’s non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), for example, are an accident “bound to happen” and, as such, avoiding this nonetheless sizable pool of resources is advisable. The Reserve Bank of India has thousands of NBFCs registered to hand out short-term loans like banks. However, the roundtablers believe very few know how to properly underwrite real estate risk nor do they appreciate how long development can take to bear fruit. And the table points out that international investors that have taken longer horizon positions, perhaps ironically, have already begun reaping the rewards. Indeed, since 2010, private equity real estate firms have made 66 exits, returning more than $3 billion to investors, according to Venture Intelligence. While in no way comparable to the mountain of overseas capital invested before the crisis, that’s still quite a leap from the $736 million returned from 10 exits between 2006 and 2009 that the data provider has recorded. “The people that had longer-term conviction and stayed with the long-term story putting capital to work in 2012, 2011, even 2010, they’ve seen the results, they’ve made money, and they’re willing to invest more,” Bedi says. Long-term investors have taken the strategic call to stay invested in India’s property markets and as such, it is unlikely the market will see such attrition as it did before. “If you know the strategy you’re following, you’re convinced about it, I think then you are able to play the long-term real estate game,” Jaggi concludes. By the time the roundtable concludes, the storm has cleared over Mumbai. The sky is still gray, but the four participants are glad to step outside for PERE’s cameraman to take photographs set against the city’s varied skyline. The property visible from the terrace ranges from greenfield developments in their infancy to completed grade A office buildings, aptly demonstrating that, even here in India’s financial stronghold, the market is still a work in progress. For these tigers who feel their survival enables them to lead investors into the next chapter for private real estate investing in India, it is work they are gladly still engaged with. Four lines of site At the end of PERE’s India roundtable participants were asked to peer into their crystal balls to provide a snapshot of what might happen in the country’s private real estate market tomorrow. Subramanian Sriniwasan, chief executive Kotak, Investment Advisors: Admitting he is going out on a limb, Sriniwasan predicts private real estate in India will benefit from much better liquidity during the next 12 to 18 months. In addition to healthier recent capital raisings the Indian government is edging closer to implementing a REIT regime which this roundtable regards as a viable exit route. Extending the point, he sees better engagement with international investors from policymakers. “So I would not be surprised if the carpet is rolled out to sovereign wealth funds and public pension funds, which means better exits and better norms for all investors,” he notes. Rajesh Jaggi, managing partner, Everstone Capital: Jaggi foretells of a private Indian real estate market where there’s more focus on commercial real estate, even perhaps as much as there currently is on the country’s residential market. Many firms are coming to see retail and commercial assets as “insurance,” Jaggi explains. Now that those sectors are becoming more mature and their prices are currently bottoming out, Jaggi predicts some exciting opportunities to materialize. “I think that’s where the running starts,” he adds. Subhash Bedi, managing director, Red Fort Capital: Bedi sees a future involving another wave of institutional capital seeking private real estate crashing on India’s shores. He cautiously welcomes it but fears there might not be enough appropriate investment opportunities to satisfy the demand. “We all tell the story, in some way, shape or form, that the lack of capital has created opportunity for people who have capital in real estate today,” he says. “Could that go away if all of a sudden a bunch of new capital came to India? Yes, it could.” Khushru Jijina, managing director, Indiareit Fund Advisors: Jijina predicts the demise of non-banking financial companies as private real estate investors. Labeling them short-term in nature and a poor underwriter of risk he says at least one will “blow up” in the next 12 to 18 months. Says Jijina “There are many opportunistic lenders in the market today who are perhaps not adequately underwriting the risks inherent in investing. There is some stress in the system and I foresee some defaults as inevitable. I fear that investors would tend to blame the sector again rather than treat these as anomalies stemming from a lack of understanding.” THE INDIA REPORT 2013 | PERE 27

© Copyright 2026