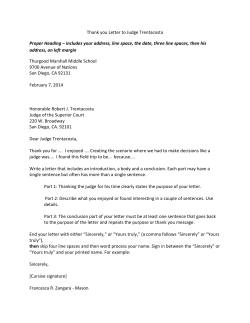

View PDF - Georgetown Law Journal