a cultural repository

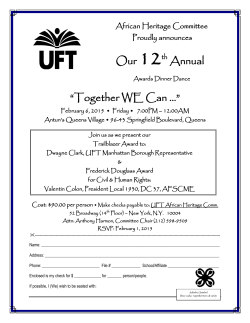

54 q&a 55 MARWAR INDIA march-april 2015 Excerpt A cultural repository Well-known business historian, researcher, academician and writer Dr D K Taknet’s many endeavours have resulted in unearthing an impressive wealth of information about Marwaris, much of which would have been lost in the folds of history if it wasn’t for his penchant for extensive research and love of the community to which he belongs. MARWAR presents an excerpt and rare photographs from his soon tobe-released coffee-table book, The Marwari Heritage, aimed at bringing to light the community’s unsurpassable contributions towards the socio-economic development of the country as well as a Q&A with the author to delve into the finer aspects of the book. Text ✲ Neehar Mishra Images courtesy ✲ Business History Museum, IIME, Jaipur Most of the projects you have undertaken have been based on the Marwari community. Considering the fact that you too are a Marwari as incidental, what led you to dedicate a major part of your professional life to studying the community in such depth? come to light. Considering the paucity of research and literature pertaining to the community, it is pertinent to bring to the fore lesser-known facts and highlight its latent characteristics in a concrete form. The community has thus always interested me and being part of it gave me an insider’s view since the very beginning of my research. What most people don’t know is that the Marwari community also actively participated in the Indian Independence movements, be it the First War of Independence in 1857 that was a defining moment in our freedom struggle, or the economic reconstruction in the ‘90s. It is indeed strange that till date historians have not given due consideration to this fact and the contribution of Marwaris has not Let’s talk about your upcoming book, The Marwari Heritage. What objectives did you have in mind when you first decided to write it? The Marwari Heritage attempts to be, for the first time in the annals of Indian history, a large format, aesthetically produced and richly illustrated coffee-table book that includes significant achievements Facing page (clockwise from top): A Marwari trader concentrating on his bahi-khata (accounts); The bahi-khata is placed before the idols of Lord Ganesha and Goddess Lakshmi for worship by the businessmen on the occasion of Diwali; By the mid19th century, the Marwari community had amassed a large amount of wealth in British India and held sway over Rajputana. The rajas even started the tradition of visiting the houses of renowned traders on special occasions. 56 q&a MARWAR INDIA march-april 2015 Excerpt of Marwaris in the fields of business, industry, the freedom movement and other spheres of life along with a discourse on the geo-socio-cultural factors which have contributed to their phenomenal growth and prosperity. The book will also highlight the welfare activities pioneered by this philanthropic community, the first to have a recorded history of CSR even before the term became known in the business sphere. Accompanied with rare, original sketches and photographs that complement the text, the main objective of the book is to publish our research study in a distinct and lucid style to acquaint its readers with the myriad noteworthy characteristics and hitherto unknown trivia about the community. What are some of the primary and secondary sources from where you have gathered information for the book? Primary data has been gathered from personal interviews with munims, gumastas [agents] and entrepreneurs of the community. Our research team travelled over 3,50,000 km and spent more than 2,000 days researching and interviewing over 8,000 people directly or indirectly associated with the community—ranging from those in the capacity of Chairman Emeritus to service-class Marwaris. People from diverse backgrounds poured their hearts out to narrate fascinating stories, replete with previously unrecorded facts, inspiring anecdotes, opinions and vignettes, providing dramatic insights into the community. The team diligently pored over approximately 2,75,000 sheets from various archives, apart from other data like personal records, memoirs, diaries and ledgers, British gazetteers, census reports, biographies, daily newspapers, journals and reports of conventions and conferences held periodically. Research data has been collected from various national and international libraries, museums and private collections. From conceptualisation to research and finally publishing, approximately how much time did it take for you to finish the book? The Marwari Heritage is the result of thorough and meticulous research of five years, going back over 400 years to capture the community’s rich history. Comprising over 500 pages, the book is embellished with more than 800 rare coloured and black-and-white photographs, lithographs, paintings, etchings, line drawings and other never-seen-before illustrations. What is the one characteristic of the multifarious Marwari community that you found especially striking while researching for your book? Left: Dr D K Taknet; Below: It took almost three months for the Marwari migrants to reach Assam. They had to cross the Brahmaputra river in boats and battle against the rough strong currents. No wonder then that it was said: ‘Jahan na pahunche bailgadi, wahan pahunche Marwari’ (Marwaris can reach any place, even those which are inaccessible by a bullock cart). During the course of the research, it was established that among Indian business communities, the Marwaris were the first community to have spent more than `25,000 crore on various welfare activities between the first and the 21st century. I came across several interesting anecdotes The book will highlight the welfare activities pioneered by this philanthropic community, the first to have a recorded history of CSR even before the term became known in the business sphere. 58 q&a MARWAR INDIA march-april 2015 Excerpt that support this. For instance, once G D Birla asked his elder brother, Jugal Kishore Birla: “Bhaiji, you are giving money to these people; out of them 99 per cent are undeserving.” His brother smiled but gave no answer. G D Birla repeated his question. This time Jugal Kishore turned to him and said: “You think that only one per cent of these people are deserving; I am only concerned with that one per cent. The remaining 99 per cent will be taken care of by the Almighty. I am not worried about them.” Another example is that of Sohan Lal Duggar, a renowned philanthropist and speculator who donated crores of rupees to various charitable causes. During his lifetime he never constructed a house for himself and instead gave away his money to needy people. These instances have created a deep impact on me and I hope they will inspire the readers of my book as well as future generations of Marwaris. What are the challenges that you most often face during your academic and literary pursuits? Sustaining research, procuring original paintings and contacting old and established business houses for photographs and old business documents is no easy feat, as you can imagine. Finances and manpower are crucial and so is the organisation of data. According to you, what are some of the most crucial ways in which Marwaris have contributed to the growth and development of the country in terms of economy, infrastructure and also culture and society? Analysts attribute the Marwaris’ significant contribution to the socio-economic development of India to their foresight which leads them to invest in the latest technology in order to drive products and production forward. Their focus on in-house research and innovation to achieve low-cost manufacturing without compromising on quality has also enabled them to offer their customers products which are good value for money. In the years past, Marwari industrialists have constantly been increasing their wealth, sales Top to bottom: A business postcard dispatched to business associates on Diwali (dedicated to Lakshmi, the Goddess of wealth and prosperity); The facsimile of an interesting advertisement that appeared in a local newspaper for Marwari traders to set up an agency in London; Muria is a bare-headed script which was adopted for writing accounts by indigenous Marwari bankers, known as Mahajans and Sarafs, in the northern and western parts of the country. Its alphabet is based on Devanagari 60 q&a 61 MARWAR INDIA march-april 2015 Excerpt Analysts attribute the Marwaris’ significant contribution to the socio-economic development of India to their foresight which leads them to invest in the latest technology in order to drive products and production forward. and profits. They have pioneered several products and manufacturing systems at the national and international levels. Marwaris deserve full credit for giving new direction to the country’s economy and their recent participation in global economy. They have also equally contributed to the socio-cultural growth of the country. Hence, several Marwaris have been awarded by various organisations, including the Padma Awards conferred by the Government of India, for their contribution in various spheres of life. Of the innumerable well-known Marwaris you have gotten to know closely while researching on them, please mention few of the names you find most noteworthy and why. Shri G P Birla, a great industrialist and philanthropist who took a keen interest in empowering the youth of the country; businessman and dedicated humanitarian Shri B M Khaitan; Shri Rahul Bajaj, a visionary entrepreneur with an appetite for risk; Shri Kamal Morarka, an extraordinary statesman, industrialist and philanthropist; Shri B H Jain, who has revolutionised Indian agriculture by infusing it with the most advanced technologies; mining baron Shri Narendrakumar A Baldota, who is a frontrunner in CSR; renowned politician and president of the All India Vaish Federation, Shri Ramdas Agarwal; and Shri N R Kothari, an exquisite jeweller and chairman of KGK Group are but few of the many names that come to my mind. Clockwise from top: The scene of a typical Marwari gaddi. The seth is seen here along with three other munims checking his bahi-khata; A scene depicting mass migration of Marwaris from their native place. Boarding a train packed with migrants was a mammoth and herculean task. Once missed, travellers had to wait for 12 to 24 hours at a stretch for the next train; A busy Marwari gaddi where four generations are seen working in unison. A photo of the great grandfather on the wall seems to shower blessings on them The leaders profiled in the book represent only a small cross-section of this ambitious cartel of businessmen and women, who deserve a salutation for their laudatory contribution to the country. You have unearthed a vast wealth of information on the Marwari community, majority of which would have been lost in history if it wasn’t for your academic endeavours … We have set up a Business History Museum under the aegis of the International Institute of Management and Entrepreneurship (IIME) in Jaipur where we collect rare material related to the Marwari community such as articles, books, souvenirs, biographies, individual collections, historical documents, British gazetteers, census reports, old account books and business documents. We even have plans to establish a museum dedicated to the community, where innovative products, rare visuals, letters, dresses, old magazines, photographs, paintings, lithographs, maps, illustrations, line-sketches and other valuables and objects will be exhibited for the benefit of scholars, general public and youth of India. What are the future projects that you have conceptualised or are currently working on? Presently, research on three volumes on the socio-economic contributions of the Vaish community is in progress. This comprehensive and authentic study intends to bridge the wide chasm that prevails in the absence of dedicated research and will also include details about the multifaceted personalities and trailblazers of the community. In order to defuse the impression that Vaish is only a money-making business community, it has become imperative to highlight its rich heritage and glorious traditions. Additionally, two other research projects, Heritage of Rajasthan and Heritage of Oil are in the pipeline, since both are crucial areas of research and there is no comprehensive book available on the either subjects. ✲ 62 q&a 63 MARWAR INDIA march-april 2015 Excerpt Excerpt from Dr D K Taknet’s upcoming book, The Marwari Heritage ... THE MIGRATION STRUGGLE The gigantic industrial empires of the Marwaris today are the outcome of the ceaseless struggle of their forefathers during their migration. The inspiring story of this migration is one of courage, patience, hard work and endurance. During the initial stages of migration, there were hardly any means of communication or arrangements for boarding and lodging on the way. Besides, the Marwaris had little knowledge of the language and culture of the places they were migrating to. In those days, escorting camel caravans across vast expanses of desert infested with sand dunes was like confronting death, and they were frequently preyed upon as they travelled for months on camel back in scorching heat. Describing their migration, G.D. Birla observed that travelling to Bombay in those days was a dreadful experience. The nearest railway station to Delhi then was either Ahmedabad or Indore. Travelling on camel back from Ahmedabad, Indore or Pilani was extremely taxing. The journeys were undertaken in groups called sagas and it took almost twenty days to undertake the journey from Pilani to Ahmedabad, death stalking the travellers at every step. But nothing slackened their pace of migration. A journey to Bengal at that time implied travelling for months at a stretch on camel back, on foot or by bullock cart and then in boats. The Marwaris had to encounter thieves, dacoits and wild animals in dense forests, and had to cross a number of rivers and nullahs on the way. Traders from Rajputana frequently travelled on foot to Mirzapur when the area came under British control and although many died in the process, this did not deter those who followed. The journey to Assam was fraught with even greater dangers. Many died of diseases caused by germs and mosquitoes and it was often ten to fifteen years or more before they were able to rejoin their families, with the latter receiving no information about their fate or well-being in the interim. It was only occasionally when a trader returned home that he brought news and correspondence from his fellow brethren. RECIPE TO SUCCESS The adverse geographical conditions in the land of their origin also gave rise to the virtues of patience, endurance and resourcefulness. Hardworking by nature, it is no surprise that their business ventures became profitable right from the start. However, what was most commendable was their intrinsic ability to spot opportunities and capitalise on them. Where another businessman would hesitate, wait and rethink, a Marwari would immediately calculate the pros and cons, and act. Perhaps this ability to judge quickly and take calculated risks could also be best attributed to the inherent hardiness of the Marwari mind and body which had dealt with the tribulations of growing up in a stark desert land. Respect for centuries-old culture values and facilitating support systems for their fellow Marwari businessmen led them to extend economic assistance to their fellow businessmen. Those who had migrated to Calcutta, Delhi and Bombay opened basas or hostels, charging nothing or very little for a year’s boarding and lodging. These basas enabled younger migrants to settle down in a new city and establish their business without financial tension. The experienced businessmen shared business strategies and insights with the newcomers. Imbued with a strong sense of community, they preferred employing relatives to ensure trust and loyalty. Jagat Seth helped many Oswals settle in Murshidabad; Surajmal Jhunjhunwala of Chirawa and Nathuram Saraf of Mandawa recruited many Marwaris for the textile trade in Calcutta, as did the firm of Tarachand Ghanshyamdas. The Birlas too followed the same practice. Marwaris encouraged enterprise among each other and promoted the economic development of their community by setting up institutions like the Marwari Association of Calcutta, the Marwari Chamber of Commerce, All India Marwari Federation and the All India Marwari Yuwa Manch. A deep-seated sense of religious and spiritual beliefs dictated that their personal lives were free from excesses. Leading simple, austere lives, they kept their business expenses to the minimum and spent very little on themselves. However, they were generous and lavish when celebrating marriages and festivals. Following the credo: ‘Pisa kan piso aawe – money earns money,’ they believed in saving money for a rainy day. The Chand magazine described how the Marwaris set up their gaddis furnished with pillows and bolsters, and transacted deals worth lakhs of rupees every day, and at night converted their gaddis into beds! Such thrift was symbolic of their love for and their responsibility towards home and family. Most of their profits were sent back to Shekhawati where joint family systems flourished. It was only due to the reassurance that his family would be looked after by his relatives that a young Marwari ventured forth to unknown lands in search of economic prosperity. The joint family system also encouraged cooperation and multiplied capital, thus becoming a huge contributory factor in the Marwari success story. A typical Marwari trader, seated comfortably against a bolster, enters the accounts in the bahi-khata. What cannot be ignored when it comes to capital accumulation is that the Marwaris were perhaps the country’s first investment bankers, having started the hundi purja system. Rather than merely hoarding their profits and savings under their mattresses, a group of established Marwaris would often collect funds and lend them to potential entrepreneurs who needed capital, charging them an interest. A dual purpose was served through this. The businesses that they encouraged the new entrepreneurs to start were actually ancillary services that would support their own business, thus allowing it to grow further. For example, a textile manufacturer would support his cousin who wanted to start a firm that made dyes. In this manner he strengthened his own business. With a genetic ability to calculate debit and credit, and profit and loss, accounts and finance became their forte. Young boys were often included in discussions regarding trade, and developed an enviable ease for arithmetic calculations. When the time came for these youngsters to either take over their father’s business and expand it, or start out on their own, they already had a good understanding of economics, and easily overtook their peers with their business acumen. Added to this intrinsic monetary understanding, the vigorous practical training they were given in their early teens, especially when it came to serving customers or handling the books of accounts, held them in good stead. It strengthened their understanding of customer needs, making them open to technological innovation and advancements to ensure consumer satisfaction. Consequently, they enjoyed a goodwill and long-term relationship with their customers. It was common to hear about Marwaris in the late eighteenth century selling off their goods at a loss or borrowing money at high rates of interest to pay off a loan in order to keep their goodwill within and outside their community. The trust that these pagdiwalas commanded was one of the main reasons they were appointed as agents in British firms. Their English-speaking ability was another factor that gave them an upper hand in the pre-Independence era. Anticipating business opportunities, Marwari traders were one of the first in the country to learn the Queen’s language. Moreover, their scrupulous trade practices combined with their reliability quotient and reputation for prudence in economic matters assured them more business than their contemporaries. Capitalising on economies of scale, the Marwaris earned quick profits in deals where others saw no opportunity. One such method was selling off large quantities Right:The Marwaris migrated from Rajputana due to geo-socio, economic and political factors. They journeyed on foot in groups for greener pastures of livelihood with small bundles and lota-dor as their only luggage. of goods at low prices; this was called rasksas in their parlance. These seths also had the knack for predicting future trade fluctuations and made huge profits in speculation. Strong community ties further helped them touch base with other businessmen of their community in different regions, thus giving them insider knowledge that few others were privy to. Sharing this sense of brotherhood, they often entered into business partnerships, which not only made obtaining capital easier, but also spread the risk. Such were their personal relationships that these partnerships usually lasted a lifetime. Most Marwari industrial houses were started in partnerships and evidence of the trend can be seen even today. Their main focus on wealth can also be attributed to their religious beliefs. The cornerstone on which the Marwaris built their enterprises could well be attributed to the ninth sutra of the Rig Veda which states: ‘May God make us men of action. We should give up laziness and, functioning with fair means, we should acquire tremendous wealth ... ’ Placing their accounts books, pen and ink in front of the Goddess during Diwali, they worshipped Lakshmi in the form of money, Saraswati in the form of bahi, and Kali in the form of black ink. Thus business was practised with a righteous zeal that precluded any nefarious practices. No wonder success was always at their doorstep … Published by The International Institute of Management and Entrepreneurship (IIME), Jaipur, The Marwari Heritage is due for release between April and May 2015. For more details contact IIME, Jaipur at [email protected] or 01412620111.

© Copyright 2026