Emerging Markets Finance and Trade Effect of Internationalization

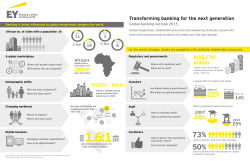

This article was downloaded by: [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] On: 09 April 2015, At: 17:38 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Emerging Markets Finance and Trade Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/mree20 Effect of Internationalization on the Cost Efficiency of Taiwan’s Banks Cheng-Ping Cheng, Lien-Wen Liang & Chen-Ta Huang Published online: 08 Apr 2015. Click for updates To cite this article: Cheng-Ping Cheng, Lien-Wen Liang & Chen-Ta Huang (2014) Effect of Internationalization on the Cost Efficiency of Taiwan’s Banks, Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 50:sup6, 204-228, DOI: 10.1080/1540496X.2014.1013857 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2014.1013857 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/termsand-conditions Effect of Internationalization on the Cost Efficiency of Taiwan’s Banks Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 Cheng-Ping Cheng, Lien-Wen Liang, and Chen-Ta Huang ABSTRACT: We focus on the effect of internationalization on the cost efficiency of banks by studying Taiwan as a sample for developing countries. We find that (1) increasing overseas businesses and foreign exchange deposits increases cost efficiency; (2) expanding offshore banking units increases bank efficiency; and (3) the profitability of a bank’s overseas branch is not a critical factor behind the differences in cost efficiency across both financial holding company (FHC) banks and non-financial holding company (non-FHC) banks. Finally, our metafrontier empirical results illustrate that FHC banks in Taiwan show better technical performance in cost control than non-FHC banks. KEY WORDS: banking efficiency, internationalization, metafrontier approach, stochastic frontier approach. The internationalization of banks began several centuries ago and is still undergoing a continuous process of development (Lothian 2002). Many studies in the literature explore the motivations and modes of entry of internationalization (Batten and Szilagyi 2011; Focarelli and Pozzolo 2008), the relationship between internationalization and the performance of banks (Bayraktar and Wang 2004, 2005; Outreville 2010), and the bank risks resulting from national regulations and internationalization (Klomp and de Haan 2012; ul-Haq et al. 2012). While several researchers have attempted to analyze the profitability and profit efficiency of globalized banks (Buch et al. 2011; Claessens et al. 2001), there are limited research studies covering the effect of internationalization on the cost efficiency of banks. The literature of internationalization explores a variety of topics with respect to developed countries, such as Australia, Canada, Germany, Japan, and the United States (Batten and Szilagyi 2011; Buch et al. 2011), but few look at these topics with respect to developing countries. Taiwan is one of the most successful examples of a developing country. The internationalization of its financial system started in the 1980s but has only in the 2000s reached its peak. Therefore, studying the effect of internationalization on Taiwan’s economic performance provides a good sample for developing countries. Financial internationalization has been achieved in Taiwan through several means. At its early stage in the 1960s, Taiwan’s government opened the market to foreign banks, enabling them to set up business branches. By the end of 2010, 31 foreign banks had set up 132 branch offices in Taiwan. Following the boom in outflowing foreign direct investment (FDI) by Taiwan businesses and the potential foothold in international financial markets in the 1990s, Taiwan banks set up branch offices abroad. As of 2010, Taiwan Cheng-Ping Cheng ([email protected]) is an associate professor in the Department of Finance at National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Douliou, Taiwan. Lien-Wen Liang ([email protected]), corresponding author, is an associate professor in the Department of Banking and Finance at Chinese Culture University, Taipei City, Taiwan. Chen-Ta Huang ([email protected]) is an authorization clerk with the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited, New Taipei City, Taiwan. Emerging Markets Finance & Trade / November–December 2014, Vol. 50, Supplement 6, pp. 204–228. © 2014 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. All rights reserved. Permissions: www.copyright.com ISSN 1540–496X (print) /ISSN 1558–0938 (online) DOI: 10.1080/1540496X.2014.1013857 Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 November–December 2014, Volume 50, Supplement 6 205 banks had 251 overseas affiliates, including 88 overseas branches, 36 overseas representative offices, and 127 subsidiaries. Another important means for internationalization of Taiwan’s banks is using offshore banking units (OBUs) to handle international business. The OBU channel is extremely important for Taiwan’s outward FDI into China because China has not largely opened up its financial market. Following the dramatic increase in trade and FDI between Taiwan and China, the scale of OBUs has grown quickly and has become an important path for Taiwan’s financial internationalization. Although not many studies target the effect of internationalization on the cost efficiency of banks, many clues can be found from the literature to support the possible relationship between cost performance and internationalization. For example, going international implies that firms can spread fixed costs, such as operating overhead and research and development expenditures, through a greater scale and scope (Markusen 1984). Internationalization offers firms opportunities to advance administrative technology about domestic markets from their international market experience, thus likely improving their competitiveness (Yuan 2008). Operating in foreign jurisdictions allows firms to access production factors at a lower cost (Porter 1990). Internationalization also permits firms to cross subsidize their domestic operations and provides greater opportunities for price discrimination and tax and price arbitrage (Yuan 2008). Internationalization attracts more stable sources of funds to expand the scale and scope effects of the domestic financial sector. Moreover, since internationalization is related to domestic financial deregulation, it influences the quality and competitiveness of domestic financial services providers (Claessens and Glaessner 1998). Taiwan in recent years has adopted financial policies seeking to liberate restrictions on trade with, and investment in, China. Policy highlights include the financial Memorandum of Understanding sealed between Taiwan and China in November 2009 and the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement signed in June 2010. The Taiwan government and local banks now have to find a way to ensure a solid foothold in China’s massive financial market in the context of competition from giant international players. After the Financial Holding Act was instituted in 2001, many Taiwan banks were merged into financial holding companies (FHCs) in an attempt to integrate their business and to save management costs. Although a major part of the relevant literature shows that there is a significant difference in the general structure and in many other parts of management between FHC banks and non-FHC banks, most studies on the management performance of banks do not clearly distinguish between these two groups. Therefore, this paper intends to explore the issues of whether different internationalization effects exist between the two groups of banks and on the possibility of constructing a metafrontier cost function based on the two groups’ cost frontier functions. We use the stochastic frontier analysis method to investigate the uncertain relationship between the extent of internationalization and the cost efficiency of Taiwan’s banks. We treat a bank as an intermediate financial institute for the transfer of resources from inputs to financial services. We set up a translog-type cost frontier function that specifics multiple inputs and outputs. Our data are mainly from the database of the Taiwan Economic Journal in which we look at thirty-two banks between 2002 and 2009. To select a set of effective variables to represent complicated international strategies, we use principal component analysis (PCA) to extract the main components of a variety of internationalization extent indexes. To build an inefficiency model, in addition to the internationalization variable, we input some control variables in the model, such as the factors of branches, profit, and risk. 206 Emerging Markets Finance & Trade Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 Following Battese and Coelli (1995), we implement the maximum likelihood estimation method to simultaneously estimate the stochastic cost efficiency model and the inefficient model. By respectively estimating the effect of the extent of internationalization on the cost efficiency of Taiwan’s FHC banks and non-FHC banks, we are able to determine the critical factors that affect the cost inefficiency of these two kinds of banks. Finally, to compare the different performances among all of Taiwan’s banks, we calculate the technology gap ratio and meta-cost efficiency for all FHC subsidiary banks and non-FHC banks using the metafrontier approach of Battese et al. (2004). Review of the Literature Internationalization and Efficiency of Banks The internationalization of finance and the globalization of financial markets are not new phenomena. They are part of an evolutionary process that began in the eleventh century and has continued. What we are seeing today is the latest and most advanced manifestation of this process (Lothian 2002). There are many studies throughout the literature that cover bank internationalization. One of the important issues in the literature is the motivation for bank internationalization.1 There are two major but opposite theories about cross-border bank expansion. The “follow the client” thesis states that the cross-border expansion of banks is a by-product of internationalization in manufacturing because banks follow their home clients when they operate abroad. A more recent trend emphasizes that in a number of cases, the pattern of cross-border expansion is independent of the relationship with home country clients and is instead shaped by the opportunity to profit from financial services in the foreign market. Batten and Szilagyi (2011) find that internationalization of Japan’s banks appears to be at odds with customer-related motivations, although such a low-risk strategy is consistent with the effects of asymmetries in information and risk aversion. However, this debate has not yet reached a definitive conclusion (Focarelli and Pozzolo 2008). Many research studies examine profitability resulting from the entry of foreign banks into the domestic banking sector (Levine 1996; Peek and Rosengren 2000). DemirgüçKunt and Huizinga (1999) show that foreign banks in developing countries tend to have greater profits and higher interest margins compared to domestic banks, while the opposite situation is true in developed countries. Claessens et al. (2001) examine foreign bank operations in eighty countries and find that foreign banks experience lower (higher) net interest margins, overhead expenses, and profits than domestic banks in developed (developing) countries. Peek et al. (1999) support the perspective that domestic banks have better performance than foreign banks for banks operating in the United States. Nolle (1995) also concludes that, according to aggregate profits, foreign-owned banks are not as profitable as domestically owned banks in the United States. After the global financial tsunami in 2008, some researchers began to target the contagion of risk in the international banking context, thus exploring the relationship between bank internationalization and risk (ul-Haq et al. 2012). Klomp and de Haan (2012) study the effect of bank regulations and supervision on banking risk by examining twenty-five indicators of banking risk. They find that banking regulation and supervision affect the risks of high-risk banks. Berger et al. (2013) investigate the effects of bank internationalization on risk taking. They show that internationalization increases bank risk taking: the Z-score of U.S. banks that engage in foreign activities is lower than that Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 November–December 2014, Volume 50, Supplement 6 207 of their purely domestic peers. Their results are consistent with the empirical dominance of the market risk hypothesis, whereby internationalization increases banks’ risk due to market-specific factors, rather than the diversification hypothesis, whereby internationalization allows banks to reduce risk through increased diversification of their operations (Berger et al. 2013). Whether internationalization increases efficiency and productivity is part of the story of the general performance and competitiveness of banks. Berger et al. (2001) consider two alternative hypotheses to explain differences in the performance of foreign and domestic banks. The home-field-advantage hypothesis argues that domestic banks generally outperform foreign banks because of informational and cost advantages. The global-advantage hypothesis states that foreign banks possess sufficient efficiency gains to overcome any home-field advantages. Berger et al. (2001) find that domestic banks exhibit higher cost and profit efficiencies than foreign banks, supporting the home-fieldadvantage hypothesis. However, they also present some support for the global-advantage hypothesis; that is, foreign banks from the United States generally exceed the cost and profit efficiencies of domestic banks. Bayraktar and Wang (2004, 2005) show that foreign banks play a statistically and economically significant role in improving the efficiency and competitiveness of domestic banks by reducing costs, profits, and net interest margins. Lensink and Hermes (2004) note that foreign banks might increase the quality of human capital in the banking system either by importing highly skilled bank managers to work in their branches or by training local employees. Outreville (2010) suggests that the relationship between international diversification and performance may follow a S-shaped curve. Firms can further their own internationalization using the strong competencies that they have developed over time in foreign markets. However, it is difficult for a firm to assess when it is overinternationalized. Most research shows that foreign bank entry increases the efficiency of the domestic banking sector. However, some studies conclude that banks with higher foreign bank ownership involvement are associated with higher efficiency (Claessens et al. 2001; Hasan and Marton 2003). Regarding the theory of productivity and efficiency, the effect of internationalization on a bank’s performance can be analyzed by technical efficiency, cost efficiency, and profit efficiency. Many research studies analyze technical efficiency by the data envelopment analysis approach, but the stochastic frontier analysis (SFA) approach is also an effective method for analyzing profit efficiency and cost efficiency. For example, using a profitefficiency model, DeYoung and Nolle (1996) conclude that foreign banks have a distinct disadvantage in terms of input inefficiency rather than output inefficiency, primarily as a result of expenditures on purchased funds. The Internationalization of Taiwan Banks When Taiwan joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, it committed to several actions within the financial services sector: (1) deregulation of the restrictions on foreign banks establishing branches and representative offices in Taiwan; (2) elimination of the ceiling level of New Taiwan dollar (TWD)–denominated deposits that foreign banks may hold; (3) enablement of foreign insurance companies to operate in Taiwan; (4) elimination of the bans on banks providing underwriting and certification services for commercial paper; (5) enablement of foreigners to establish billing companies in the financial ser- Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 208 Emerging Markets Finance & Trade vices sector; and (6) relaxation of limitations on foreign investment in foreign currency brokerages. Since then, Taiwan’s banking sector has continued in the direction of further deregulation and liberalization. Table 1 shows that, as of the end of March 2010, 31 foreign banks had set up 132 branch offices in Taiwan. Another 13 foreign banks had established representative offices on the island. These foreign banks have brought with them a great number of techniques and experiences in handling financial asset securitization. As of March 2010, Taiwan’s financial sector boasts 88 overseas branches, 36 representative offices, and 127 other affiliates. Figure 1 shows the distribution. Following the trend for expansion, Taiwan’s domestic banks have quickened their pace of internationalization and rapidly increased their number of overseas affiliates in the form of overseas branches, representative offices, and other affiliates. Taiwan banks have 251 overseas affiliates as of March 2010. Of the 88 overseas branches, the largest number are in the United States (22), followed by Hong Kong (18). Of the 36 overseas representative offices, Vietnam has the most (13), followed by China (9). Of the 127 subsidiaries, the largest number are in the United States (47), followed by the Philippines (25) and Vietnam (25). Most Taiwan banks select the United States as a host country (70), then Vietnam (46), the Philippines (29), and Hong Kong (26). To bring Taiwan’s financial regulations closer in line with international business practices, Taiwan’s government launched the Financial Institutions Merger Law and Financial Holding Company Act on December 13, 2000, and July 9, 2001, respectively. These two legislations were formed by making reference to the operational systems of financial holding companies with stipulations pertaining to the mergers and acquisitions (M&As) of financial institutions in Japan, the United States, and other countries. The enacted regulations allow foreign banks to set up wholly owned subsidiaries in Taiwan through direct investment or M&As. To promote OBUs as a capital control center for Taiwan businesses, the government has gradually amended parts of the Regulation for the Implementation of the Offshore Banking Act in recent years. For instance, in March 2008, the Financial Supervisory Commission loosened OBUs’ restrictions on credit limits for Taiwan businesses operating overseas. Collaterals are not a concern anymore. The maximum is universally set at 30 percent of the net value of assets. The government also allows OBUs to conduct a factoring of business for any transactions inside China. It also permits OBUs to grant credits to Taiwan businesses after accepting local stocks, real estate properties, and other TWD-denominated assets as collateral. The overseas branch offices of Taiwan banks involved in international banking not only serve as capital control centers for Taiwan businesses, but also boost profits for the banking industry back home. These overseas branches have played an essential role in ensuring a foothold for Taiwan banks in the international financial sector. While Taiwan’s economy had been growing rapidly in the 1980s, its old-fashioned banking sector was unable to cope with the needs that accompanied soaring economic development. In 1989, the government decided to initiate deregulation in the banking industry and approved the establishment of new banks. By 1992, sixteen new banks were allowed to operate, and state-owned banks were becoming privatized. Trust investment firms, small- and medium-size enterprise banks, and credit cooperatives transformed themselves into commercial banks, one after another. Taiwan’s financial industry thus officially entered an era of fierce competition. In 2001, Taiwan became a member of the World Trade Organization, and in the same year, the government passed the Financial 36 36 35 36 33 32 32 32 31 68 69 67 68 64 83 141 133 132 Branches 104 105 102 104 97 115 173 165 163 Total 78 80 80 79 82 82 84 88 88 Branches 30 31 33 38 39 34 35 35 36 Representative offices 70 73 78 86 101 120 123 126 127 Others 178 184 191 203 222 236 242 249 251 Total Number of overseas branches of domestic banks Source: Overview of Banking Sector, Banking Bureau, Financial Supervisory Commission. 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 (March) Head office Number of local branches of foreign banks Table 1. Overview of the internationalization of banks in Taiwan Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 0.50 0.63 0.69 0.70 0.77 0.91 0.99 0.95 — Assets of OBU (billion U.S. dollars) 209 Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 210 Emerging Markets Finance & Trade Figure 1. Overseas branches of Taiwan banks (March 2010) Source: Overview of Banking Sector, Banking Bureau, Financial Supervisory Commission. Holding Company Law and approved the establishment of fourteen financial holding companies, opening a new chapter in the development of Taiwan’s financial industry. The literature relating to studies on banking internationalization for Taiwan is limited in comparison to papers on the same issue for Europe and the United States. Huang (2010) stresses that entry location factors may affect the internationalization strategy of Taiwan banks and the relationship between the banks’ internationalization and their performances. He uses the least square dummy variable method to explore the relationship between internationalization and efficiency, although the definition of efficiency is given a less financial meaning.2 He finds that internationalization improves operational efficiency, which in turn increases financial performance (Huang 2010). Accompanying the large amount of outward FDI by Taiwanese firms, Taiwan’s banks have recently been rapidly raising their internationalization level to serve their domestic customers abroad. However, there is still a lack of any strict research on how to analyze the effect of internationalization of Taiwan’s banks on their efficiency. Therefore, we find it is worthwhile to investigate the appropriate strategies of internationalization and whether internationalization affects the cost efficiency of FHC and non-FHC banks differently. Model Specification and Variable Selection Stochastic Cost Frontier Function Following Battese and Coelli (1995), we specify the following stochastic translog cost function with three inputs and three outputs: 3 3 n =1 m =1 ln TCit = α 0 + ∑ α n ln Yn,it + ∑ β m Pm ,it + 1 3 3 ∑ ∑ δ nj ln Yn,it ln Yj ,it 2 n =1 j =1 (1) 3 3 1 3 3 + ∑ ∑ γ mk ln Pm ,it ln Pk ,it + ∑ ∑ ρnm ln Yn,it ln Pm ,it + νit + uit . 2 m =1 k =1 n =1 m =1 Here, TCit represents the total cost of the decision-making unit; Yn is the nth output (loans, investment, and noninterest income, respectively); Pm is the mth input price (price of funding, labor, and capital, respectively); and i is the banking firm. Moreover, α, β, δ, γ, ρ are the parameters to be estimated, whereby νit and uit are random error terms assumed to be mutually independent, and uit is a function of firm-specific factors that affect cost November–December 2014, Volume 50, Supplement 6 211 inefficiency. Specifically, uit belongs to a truncated normal distribution—that is, given by uit ∼ N+(mit,σ2u). We also specify the following regression model to capture the main determinants of X-inefficiency in the internationalization of banks in Taiwan: Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 mit = b0 + b1B1it + b2B2it + b3B3it + b4B4it + b5B5it + b6B6it. (2) We select six characteristic variables that might affect the cost inefficiency of banks. Detailed definitions of these variables are provided in a later section. We adopt principal component analysis to solve the multicollinearity problems that internationalization variables might have. Principal component analysis is a procedure for transforming a set of correlated variables into a new set of uncorrelated variables. This transformation is a rotation of the original axes to new orientations that are orthogonal to each other, and therefore there is no correlation between variables.3 The translog cost function is known as being flexible in the sense that it provides a second-order approximation of the true function. Taking these estimated parameters as given, we can examine whether the estimated cost function is concave in input prices. Particularly, the Hessian matrix must be negative semidefinite. In estimation, the translog cost function should satisfy the regularity condition that an input share equals the derivative of the log cost function with respect to the corresponding log input price (Allen and Rai 1996).4 We impose homogeneity restrictions by normalizing total costs and input prices through one of the input prices. In particular, we select labor price as the normalizing factor. After the normalizing process, we estimate Equations (1) and (2) simultaneously using Frontier 4.1 software. We calculate the cost inefficiency of each bank by defining the cost inefficiency function as CEit = e–uit, with 0 < CEit < 1, meaning that as CE increases, cost efficiency rises. Metafrontier Approach Following Battese et al. (2004), we use the metafrontier cost function to compare the performance among banks with different technologies. We define the observed cost function for the ith bank at the tth period by the stochastic frontier for the kth group in Equation (3): Cit ( k ) = f ( xit ( k ) , ϕ ( k ) )e νit ( k ) + uit ( k ) ≡e xit ( k ) ϕ( k ) + νit ( k ) + uit ( k ) . (3) The metafrontier function is an overarching function of a given mathematical form that encompasses the deterministic components of the stochastic frontier cost functions for firms that operate under the different technologies. Thus, we express the metafrontier cost function model for FHC and non-FHC banks by C *it = f ( xit , ϕ*) = e xit ϕ* i = 1, 2,..., N , t = 1, 2,..., T . (4) Here, Cit* is the minimum expenditure incurred by the ith firm at the tth period, and ϕ* denotes the vector of parameters for the metafrontier function such that Xitϕ(k) ≥ Xitϕ*. (5) We formulate the measure of cost efficiency (CE ) for the ith bank at the tth period as the ratio of the minimum cost to the observed cost, adjusted by the corresponding random error: * 212 Emerging Markets Finance & Trade CE *it ( k ) = e xit ϕ*+ νit ( k ) =e Cit ( k ) e xit ϕ* . e xit ϕ ( k ) − uit ( k ) (6) We calculate the technology gap ratio (TGR) for the observation of the sample bank involved by e xit ϕ* TGR = . (7) it ( k ) e xit ϕ ( k ) This results in bank k ’s meta efficiency (CE *): CE * = CE × TGR. Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 (8) Thus, the meta-efficiency scores are the technical efficiencies of each bank in different groups corrected by the technological gaps of the banks in a given group relative to the technology available to the industry as a whole. According to this reasoning, the metafrontier should be an enveloping curve of group frontiers. The parameters of Equation (3) can be obtained by solving the following linear programming (LP) equation provided by Battese et al. (2004): T N � ( k ) ) − ln f ( xit , ϕ*) , min L ≡ ∑ ∑ ln f ( xit ϕ t =1 i =1 s.t. ln f (xit, ϕ*) ≤ ln f (xit, ϕˆ(k)). (9) In the above equation, ϕˆ(k) is the estimated coefficient vector associated with group k’s stochastic frontier. Since estimated coefficient vectors are fixed for the above equation, Battese et al. (2004) define and operate an equivalent form of the linear programming. Economies of Scale and Scope We next investigate whether banks possess economies of scale and economies of scope. The economies of scale (SE) measure used here is as follows: SE = C * ( P, Y ) 3 . (10) ∑ Y C ( P, Y ) * i i i =1 * Here, C (P, Y) is the optimal cost function, and Ci* (P, Y) is the optimal cost function for output i of partial differential. If SE > 1, then a bank is facing increasing returns to scale, implying that the larger its size, the lower the cost for the bank to operate. If SE = 1, then a bank is operating at constant returns to scale. If SE < 1, then an opposite situation occurs for decreasing returns to scale, implying that the bank is at the stage of diseconomies of scale. Economies of scope exist when the total cost of a firm producing more than one output jointly is lower than the sum of the costs for producing each output separately. In the case of a bank producing three outputs (Y1, Y2, and Y3), as suggested by Mester (1996), the estimate for the degree of economies of scope (SC) is ( ) ( ) , P ) − C (Y , Y , Y , P ) . C * Y1 − 2Y1m , Y2m , Y3m , P + C * Y1m , Y2 − 2Y2m , Y3m , P SC = ( + C Y , Y , Y3 − 2Y * m 1 m 2 m 3 C (Y1 , Y2 , Y3 , P ) * (11) * 1 2 3 November–December 2014, Volume 50, Supplement 6 213 Here, Yi is the volume of output i, i = 1, 2, 3; Yim is the minimum amount of output i produced by any bank in the sample; and C *(⋅) is the optimal cost function.5 An estimate of SC greater than or less than zero indicates scope economies or scope diseconomies, respectively. Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 Variables and Data Resources Our data come from the database of the Taiwan Economic Journal and the Central Bank of the Republic of China (Taiwan). It is unbalanced panel data with fourteen subsidiary banks of financial holding companies (FHC banks) and eighteen independent banks (nonFHC banks) for the period 2002–9. We adopt an intermediation approach (Rezvanian and Mehdian 2002) to define factor inputs and outputs of financial institutions. According to Lang and Welzel (1999), the typical input factors for a bank include labor, capital, and funding. The output variables for a bank consist of loans, total investment (including short- and long-term investments), and noninterest income (including transaction fees and other forms of commercial income). Table 2 lists the definitions and summary statistics for these variables. Since they are in nominal values, we use the consumer price index to convert them into real values.6 Analysis of Empirical Results Extracting the Factors of Internationalization Following Ruigrok and Wagner (2003), Sullivan (1994), and Welch and Luostarinen (1988), we select eleven indexes that are closely related to internationalization of Taiwan’s banks: (1) the ratio of personnel costs of overseas branches to the bank’s overall personnel costs, (2) the ratio of business revenues obtained overseas to the bank’s overall business revenues, (3) the assets of overseas subsidiaries, (4) the ratio of assets of overseas subsidiaries to the bank’s overall assets, (5) the pretax profits of OBUs, (6) the number of overseas branch offices, (7) foreign exchange deposits, (8) the ratio of personnel costs of OBUs to the bank’s overall personnel costs, (9) the ratio of business revenues of OBUs to the bank’s overall business revenues, (10) the ratio of pretax profits of overseas branches to the bank’s overall profits, and (11) the pretax profits of overseas branches. To simplify the preceding variables, we use the PCA method to extract the principal components from the eleven indexes as the representative indexes of bank internationalization. KMO (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin) and Bartlett’s tests are two statistic benchmarks that are often used to examine the effectiveness of the factor analysis model. In this paper, the KMO value is 0.829 and the approximate chi-square is 2,913.805 (p < 0.000), thus confirming that the data are suitable for factor analysis. Table 3 indicates the rotated components matrix that the research seeks to analyze. The first component’s major variables include the ratio of personnel costs of overseas branches to the bank’s overall personnel costs, the ratio of business revenues obtained overseas to the bank’s overall business revenues, the assets of overseas subsidiaries, the ratio of assets of overseas subsidiaries to the bank’s overall assets, the pretax profits of OBUs, the number of overseas branch offices, and foreign exchange deposits. Because these variables are closely related to a bank’s overseas banking services, we name this component “level of overseas branch.” Loans Investment Noninterest income 645,731 186,868 52,998 0.3447 885,493 5,032 20,674 0.0179 1,137 Deposits + Borrowing Total employees Net fixed assets Interest payments / (Deposits + Borrowing) Employee salary / Total employees Operating expense / Net fixed assets 26,842 Mean (FHC) Labor cost + Capital cost + Funding cost Description Note: The samples of 14 FHC and 18 non-FHC banks are 112 and 143, respectively. Total cost (TC ) Input Fund (X1) (billion TWD) Labor (X2) (people) Capital (X3) (billion TWD) Price of funding (P1) (percent) Price of labor (P2) (thousand TWD) Price of capital (P3) (percent) Output Output (Y1) (billion TWD) Output (Y2) (billion TWD) Output (Y3) (billion TWD) Variable Table 2. Definitions and descriptions of variables 397,298 137,364 4,354 0.1676 582,785 2,084 19,611 0.0062 306 16,247 Standard deviation (FHC) 330,880 53,481 1,541 0.3603 412,636 2,625 8,066 0.0175 988 12,009 Mean (non-FHC) Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 424,504 70,908 1,336 0.2437 500,721 1,876 9,598 0.0055 275 12,942 Standard deviation (non-FHC) 214 November–December 2014, Volume 50, Supplement 6 215 Table 3. Rotated components matrix Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 Variable/ components Assets of overseas subsidiaries (OBU included) Ratio of personnel costs of overseas branches to the bank’s overall personnel costs Ratio of business revenues obtained overseas to the bank’s overall business revenues Number of overseas branch offices Foreign exchange deposits Ratio of assets of overseas subsidiaries (OBU included) to the bank’s overall assets Pretax profits of OBUs Ratio of personnel costs of OBUs to the bank’s overall personnel costs Ratio of business revenues of OBUs to the bank’s overall business revenues Ratio of pretax profits of overseas branches to the bank’s overall profits Pretax profits of overseas branches Total Percent of variance Cumulative percent Level of internationalization OBU operation Profitability of overseas branches Communalities 0.950 0.117 0.108 0.928 0.925 –0.005 –0.122 0.871 0.925 –0.036 –0.075 0.862 0.924 –0.028 0.154 0.878 0.899 0.150 0.071 0.836 0.854 0.422 0.010 0.908 0.754 –0.089 0.245 0.848 0.206 –0.035 0.671 0.728 0.315 0.735 0.038 0.641 0.180 –0.021 –0.843 0.744 0.414 –0.034 0.675 0.628 5.886 53.500 53.500 1.538 13.978 67.488 1.273 11.568 79.056 Notes: Extraction method: principal component analysis; rotation method: varimax with Kaiser normalization. The second component’s major variables include the ratio of personnel costs of OBUs to the bank’s overall personnel costs and the ratio of business revenues of OBUs to the bank’s overall business revenues. Since these variables are highly related to the business development of a bank’s OBU operation, we name this component “OBU business.” The third component’s major variables include the ratio of pretax profits of overseas branches to the bank’s overall profits and the pretax profits of overseas branches. These variables have a relationship with local banks’ intention to boost overall margins by 216 Emerging Markets Finance & Trade setting up overseas offices and expanding their overseas business. Thus, we name this component “profitability of overseas branches.” We next use the three components as the representative factors of internationalization that will be put in the inefficiency model to analyze the effect of internationalization on the cost efficiency of banks. Cost Frontier Function and Inefficiency Model Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 Cost Frontier Function Table 4 shows the empirical results of the stochastic cost frontier model and inefficiency model. First, we use the likelihood ratio (LR) test to verify whether the proposed inefficiency model is well specified. Our LR statistic for FHC banks is 96.41; for non-FHC banks, 114.79. Both significantly reject H0 and imply the suitability of the proposed inefficiency model. The Wald test results show that the majority of marginal effects of output are consistent with the condition of monotonicity for both FHC and non-FHC banks. All marginal effects of inputs satisfy the condition of nondecreasing in input prices for both groups of banks. The Wald test results of the Hessian matrix are also consistent with the conditions of concavity, although they are not all significant because we do not simultaneously estimate the cost function with shared functions (Greene and Segal 2004). In sum, the estimated translog cost functions of FHC and non-FHC banks are congruent with the cost theory. Inefficiency Model As with our above analysis, we use the method of PCA to extract three factors pertaining to internationalization: (1) level of overseas branch (LOB), (2) OBU business (OBU), and (3) profitability of overseas branches (POB). As in the related literature, in the inefficiency model we also include some control variables, such as the number of domestic branches, profit (return on assets [ROA]), and risk (nonperforming loans [NPL] ratio lagged for one period). The Pearson correlation analysis shows that all correlation coefficients among the variables are less than 0.6, meaning that no multicollinearity exists among the selected factors. Internationalization Variables Level of Overseas Branch The estimated coefficient of LOB displays a significantly negative relationship with cost inefficiency for both FHC and non-FHC banks. This suggests that the more internationalized a bank is through its overseas businesses and foreign exchange deposits, the lower its cost inefficiency, thus improving its overall operation efficiency.7 In terms of LOB, non-FHC banks are more capable of decreasing cost inefficiency than FHC banks. While both groups of banks face intense competition in the overseas markets, the FHC banks do not effectively execute strategies of diversification. In the 2000s, since a bank’s interest spread has stood at 1–2 percent, banks have limited room for making profits in the Taiwan market. If the banks upgrade the level of their overseas Coefficient 31.3487*** –1.3943 0.1604 –0.8556 2.8921** –2.0909** –0.0259 0.0714 0.0585 0.2687** 0.1909*** 0.0423 0.1063 –0.0942* –0.1145** –0.0007 Variable Constant lnY1 lnY2 lnY3 ln(P1 /P2) ln(P3 /P2) 1/2(lnY1)2 1/2(lnY2)2 1/2(lnY3)2 1/2ln(P1 /P2)2 1/2ln(P3 /P2)2 lnY1 × lnY2 lnY1 × lnY3 lnY2 × lnY3 ln(P1 /P2) × ln(P3 /P2) lnY1 × ln(P1 /P2) 10.8122 1.5732 0.9373 0.9417 1.1510 1.0591 0.1758 0.0721 0.0689 0.1094 0.0677 0.0865 0.0956 0.0482 0.0584 0.0862 SE FHCs 2.8994 –0.8863 0.1711 –0.9085 2.5128 –1.9742 –0.1474 0.9900 0.8489 2.4555 2.8179 0.4895 1.1117 –1.9542 –1.9605 –0.0087 t-value Table 4. Empirical results of the stochastic cost frontier model and inefficiency model 29.7788*** –3.5522*** 2.5704*** 0.2524 1.8603** 0.9771 0.4591*** 0.1514*** 0.0009 0.0886 0.0430 –0.1890*** –0.1176 0.0051 0.0049 0.0329 Coefficient 1.2788 0.8710 0.6663 0.9135 0.9231 0.8647 0.1190 0.0352 0.0744 0.1342 0.0536 0.0497 0.0826 0.0280 0.0674 0.0637 SE Non–FHCs Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 23.2862 –4.0781 3.8574 0.2763 2.0153 1.1300 3.8582 4.3030 0.0116 0.6601 0.8020 –3.8013 –1.4231 0.1830 0.0733 0.5170 (continues) t-value 217 0.0140 0.0202 0.0068 0.0004 0.0079 0.0030 –0.0787*** –0.0325 –0.0022 0.0015*** –0.0062 0.0012 0.0057*** 3.3792 –0.7862 0.4133 6.9142 –5.6276 –1.6073 –0.3305 –0.1745 0.3107 1.8208 –0.8651 1.3047 1.9266 t-value 0.0015** –0.0338*** 0.0024 0.0155*** –0.3554*** –0.1255*** –0.1054 –0.0718 0.0669 0.0970*** –0.1465** –0.0516 –0.2766** Coefficient 114.7946 0.0006 0.0091 0.0044 0.1242 0.0274 0.1773 0.0481 0.0454 0.0367 0.0632 0.0558 0.1258 SE Non–FHCs 2.4033 –3.6992 0.5511 4.1097 –2.8612 –4.5832 –0.5945 –1.4924 1.4744 2.6470 –2.3179 –0.9241 –2.1982 t-value Notes: LOB represents level of overseas branch; OBU is OBU business; POB represents profitability of overseas branches. The samples of 14 FHC and 18 non-FHC banks are 112 and 143, respectively. * Statistical significance at the 10 percent level; ** statistical significance at the 5 percent level; *** statistical significance at the 1 percent level. 132.1589 0.0922 0.0559 0.0479 0.0446 0.0578 0.1175 –0.0161 0.0174 0.0872* –0.0386 0.0754 0.2264* lnY1 × ln(P3 /P2) lnY2 × ln(P1 /P2) lnY2 × ln(P3 /P2) lnY3 × ln(P1 /P2) lnY3 × ln(P3 /P2) Constant Internationalization variables LOB OBU POB Control variables Domestic branches Profit (ROA) Risk (lag NPL) σ2 = σ2u + σ2ν Log likelihood function SE Coefficient FHCs Variable Table 4. Continues Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 218 November–December 2014, Volume 50, Supplement 6 219 branches and launch international banking services, then we expect their cost efficiency to be enhanced. The finding echoes Huang (2010) and Sullivan (1994). Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 OBU Business For the first decade of the twenty-first century, since the governments across the Taiwan Strait have not yet fully opened their financial markets, OBU transactions have become a major channel for financing and tax avoidance by Taiwan firms and businessmen investing in China. OBUs are thus an important source of income for banks. We find that the OBU business and cost inefficiency are negatively related for FHC and non-FHC banks, implying that expanding OBU operations helps improve bank efficiency. In 2008, the governments of Taiwan and China have relaxed restrictions on cross strait trade and financial exchanges. Statistics show that both OBU assets and the ratio of OBU business revenues to banks’ business revenues have risen sharply. As trade codependency across the Taiwan Strait deepens and liberalization and internationalization of the two financial markets increase, expanding OBU operations is expected to benefit banks’ cost performance. Profitability of Overseas Branches We find that POB displays a negative but not significant relation with operational inefficiency for subsidiary banks. For non-FHC banks, POB has a positive but not significant relation with cost inefficiency. The insignificant effects in both groups are partly because most Taiwan banks made profits only in the Hong Kong and Vietnam markets. More than one-third of the overseas branches of Taiwan banks are set in developed countries, but they did not earn significant profits. Control Variables Following Ruigrok and Wagner (2003) and Welch and Luostarinen (1988), we set the number of domestic branches, profit (ROA), and risk (lag NPL) as control variables. Domestic Branches The number of domestic branches not only indicates a bank’s scale of operations, but also helps a bank provide more-efficient services to its loan clients due to the widespread availability of branch offices. With an increase in branch offices, however, banks are burdened with higher overhead costs such as personnel costs, management costs, and office rent. In addition, instead of creating economies of scale, the head office might suffer from an inefficiency of resource allocation and then weaker operational efficiency because of an excess number of branch offices (Banker et al. 2003; Beck et al. 2005). Profit ROA is defined as a bank’s pretax profit divided by average total assets. Altunbas et al. (2000) show that ROA and the inefficiency value have an inverse relationship. We also find that ROA and cost inefficiency are negatively related. This implies that when banks 220 Emerging Markets Finance & Trade fully utilize their assets, the profitability of assets increases, and so there is an improvement in banks’ cost efficiency. Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 Risk We used nonperforming loans to proxy for risk (Berg et al. 1992; Berger and DeYoung 1997; Berger and Mester 1997; Hughes and Mester 1993; Mester 1996). To resolve a high NPL ratio, a bank in general will allocate undistributed earnings to make provisions for loan losses. Our study indicates that the NPL ratio and cost inefficiency have a positive relation, but they are not significant for FHC and non-FHC banks. However, several studies find that banks with a larger number of problem loans face reductions in cost efficiency (Berger and De Young 1997; Drake and Hall 2003; Hughes and Mester 1993). Economies of Scale Table 5 shows that the average values measuring economies of scale for FHC and non-FHC banks are 1.2119 and 1.2459, respectively, implying they are at the stage of increasing returns to scale. However, there are two FHC banks and one non-FHC bank that have economies of scale less than 1 in 2010, implying they are at the stage of diseconomies of scale, while the other twenty-nine banks are at the stage of increasing returns to scale. It is therefore appropriate for Taiwan banks to expand their sizes. Increasing offshore banking services is a good alternative under such a strategy. If SC > 0, it is beneficial for banks to jointly produce the entire array of outputs. However, if SC < 0, a bank should specialize in a single output to minimize its production costs. The average values of economies of scope for both FHC and non-FHC banks are greater than zero, meaning that the diversification of financial products always reduces costs. It is therefore beneficial for banks to expand into different lines of domestic and foreign business such as loans, investments, and others that generate noninterest income. Metafrontier Estimation Before estimating the metafrontier cost function, we first examine whether the stochastic frontier cost function of FHC banks is different from that for non-FHC banks. We set the null hypothesis as H0 : βF = βN. Our LR test statistic of 97.28 is larger than χ20.01 (28) = 48.28, so the null hypothesis is rejected. This means a difference in the stochastic cost frontier function indeed exists between FHC and non-FHC banks. Therefore, it is not appropriate to conduct a hybrid estimation by a single cost function. We should adopt the metafrontier cost function to conduct a comparison for the two groups of banks. To compare the metafrontier cost function with conventional studies, according to Equation (9), we use the LP to estimate the parameters of the metafrontier cost function. We also use the SFA to evaluate banking efficiencies by pooling all the data across groups without regard to possible technological differences. We obtain the standard errors of the mathematical programming estimators through bootstrapping methods with 1,000 replications. The estimated standard error of a metafrontier parameter is the standard deviation of the 1,000 new parameter estimates. Table 6 shows that there are substantial Scale FHC Non-FHC Scope FHC Non-FHC 1.3236 1.2220 3.5913 13.1084 3.5873 13.1071 2003 1.4253 1.2152 2002 3.3580 13.1048 1.1890 1.2857 2004 3.2711 13.1549 1.1640 1.2646 2005 3.2255 13.2330 1.1713 1.2199 2006 3.1587 13.2009 1.1291 1.2658 2007 Table 5. The economies of scale and economies of scope for FHC and non-FHC banks 3.1753 13.1654 1.1434 1.2948 2008 Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 3.2087 13.1288 1.1492 1.1966 2009 3.3220 13.1506 1.2119 1.2459 Average 221 Coefficient 7.2782 0.4982 1.5114*** –0.3555 2.8014*** 0.4596 0.1206 0.0875** 0.0636 0.3081*** 0.1537*** –0.0887* –0.0452 –0.0255 Variable Constant lnY1 lnY2 lnY3 ln(P1 /P2 ) ln(P3 /P2) 1/2 (lnY1 )2 1/2 (lnY2 )2 1/2 (lnY3 )2 1/2 ln(P1 /P2 )2 1/2 ln(P3 /P2 )2 lnY1 × lnY2 lnY1 × lnY3 lnY2 × lnY3 7.2083 0.8509 0.4790 0.5398 0.8518 0.5901 0.0874 0.0366 0.0455 0.0972 0.0367 0.0486 0.0504 0.0243 Standard error SFA–POOL 1.0097 0.5856 3.1552 –0.6587 3.2888 0.7787 1.3788 2.3870 1.3969 3.1691 4.1905 –1.8256 –0.8967 –1.0532 t-value Table 6. Empirical results of the metafrontier cost function 58.3585 0.3616 0.3090 –0.1396 1.4479 0.6756 0.6046 1.0618 1.7404 1.3156 0.9923 0.8900 0.4282 1.2269 Coefficient 4.728 0.240 0.977 0.435 0.597 0.649 0.279 0.857 0.429 1.022 0.377 0.468 0.513 0.647 Standard deviation LP 33.7384 –0.3815 –0.3240 –1.7185 0.5186 –0.0155 –0.1440 0.1728 –1.4893 –0.0336 0.4623 –0.1603 –0.1972 –0.4401 95 percent confidence Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 82.9786 1.1047 0.9421 1.4393 2.3771 1.3667 1.3532 1.9508 4.9700 2.6649 1.5223 1.9402 1.0536 2.8939 Interval 222 –0.0905** 0.0074 0.0034 0.0683* 0.0178 –0.0608 –0.0374 –0.0323** –0.0729*** 0.0071 0.0019*** –0.0210*** 0.0011 0.0123*** 0.0460 0.0546 0.0410 0.0378 0.0306 0.0424 0.0377 0.0142 0.0196 0.0087 0.0003 0.0063 0.0023 0.0012 –1.9677 0.1354 0.0824 1.8059 0.5834 –1.4334 –0.9931 –2.2757 –3.7238 0.8239 5.8146 –3.3413 0.4735 10.4034 0.8534 1.0669 0.7424 –0.5128 0.8483 0.4303 0.7259 0.4196 0.7738 0.6712 1.5876 0.4504 0.0132 0.823 1.032 0.361 1.578 2.460 0.672 0.552 1.566 0.280 0.955 2.379 0.638 1.598 –1.0701 –2.5016 –0.5225 –2.2246 –0.0778 –0.3141 –0.2262 –0.1287 0.1728 –1.9665 0.9416 –0.4734 –2.7869 * Statistical significance at the 10 percent level; ** statistical significance at the 5 percent level; *** statistical significance at the 1 percent level. ln (P1 /P2 ) × ln(P3 /P2 ) lnY1 × ln(P1 /P2 ) lnY1 × ln(P3 /P2 ) lnY2 × ln(P1 /P2 ) lnY2 × ln(P3 /P2 ) lnY3 × ln(P1 /P2 ) lnY3 × ln(P3 /P2 ) INT OBU Pro Branches ROA Lag_NPL σ 2 = σu2 + σν2 Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 2.7769 4.6354 2.0072 1.1989 1.7744 1.1746 1.6780 0.9680 1.3747 3.3089 2.2337 1.3742 2.8133 223 Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 224 Emerging Markets Finance & Trade Figure 2. Technology gap ratio of FHC banks and non-FHC banks Figure 3. Meta-cost efficiency of FHC banks and non-FHC banks differences between the metafrontier coefficients and the corresponding coefficients of the SFA for the entire sample. As shown in Figure 2, the estimated technology gap ratio (TGR) stands somewhere between 0.969 and 0.661. The average TGR of FHC banks is 0.871, whereas that for non-FHC banks is 0.826. From Figure 2, it is obvious that the TGR for FHC banks is mostly greater than that of non-FHC banks, meaning FHC banks present a better technical performance. Figure 2 also shows that, except in 2002, the average TGR of FHC banks is larger than that of non-FHC banks. An important reason for this is that the passage of the Financial Holding Company Act in 2001 allows FHC banks to provide one-stop shopping like a financial department store, and this offers a significant cost advantage. The meta-cost efficiency between the two groups is between 0.514 and 0.867, as shown in Figure 3. The average meta-cost efficiency of FHC banks is 0.606, whereas that of non-FHC banks is 0.733. From Figure 3, it is clear that the meta-cost efficiency value of FHC banks is significantly lower than that of non-FHC banks. This shows that bank liberalization and internationalization harmed FHC banks’ operations during Taiwan’s credit card crisis in 2005, the U.S. subprime mortgage crisis in 2007, and the global financial tsunami in 2008. Conclusion Taiwan’s banks have recently upgraded their internationalization levels and increased their number of overseas affiliates due to the outward FDI clustering sites of Taiwan-based Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 November–December 2014, Volume 50, Supplement 6 225 firms in China and Southeast Asia countries (Huang 2010). Although some studies assert that internationalization can successfully facilitate competition in a domestic banking sector and achieve economies of scale and scope (Huang 2010), different factors of the internationalization process might result in an inconsistent effect on different types of banks. Through the PCA method, we use three factors pertaining to internationalization of Taiwan banks: (1) level of overseas branch, (2) OBU business, and (3) profitability of overseas branches. We find that, in general, the greater the number of overseas branches a Taiwan bank has, the higher its cost efficiency. This suggests that the more internationalized a bank is through overseas businesses and foreign exchange deposits, the lower its cost inefficiency, which thus improves its overall operation efficiency. We also find that non-FHC banks are more able to decrease cost inefficiency than FHC banks. This indicates that FHC banks must improve their efficiency in executing an overseas diversification strategy. Expanding OBU operations greatly improves the performances for both groups of Taiwan banks due to lower transaction costs in conducting international business through OBUs. Although the economic relationship across the Taiwan Strait has significantly improved, it is not expected that the governments of Taiwan and China will fully open their financial markets in the immediate future. The channel of OBU is still mainly used for financing and tax avoidance by Taiwan firms and individuals investing in China. Therefore, Taiwan’s banks should try to expand their OBU assets and increase the ratio of OBU business revenues to gain more profit. Through the metafrontier model, the technology gap ratio (TGR) estimated herein is greater for FHC banks than for non-FHC banks, meaning that FHC banks present a better technical performance. However, the average meta-cost efficiency of FHC banks shows that the group of non-FHC banks has a lower cost frontier. It is therefore the attainable objective of FHC banks to reduce cost through a suitable administration adjustment. Because banks’ interest spread in recent years has stood at 1–2 percent, Taiwan’s banks have limited opportunities to make profits in the domestic market. To increase their profits as well as their cost efficiency, these banks should closely follow Taiwan manufacturing firms investing abroad in order to upgrade their internationalization strategies, such as launching international banking services and increasing their OBU business. Since Taiwan signed the financial Memorandum of Understanding and Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement with China, another booming area for Taiwan banking is expected to follow the local information technology industry over to China. Whether Taiwan’s banking industry is able to take advantage of the great potential business across the Taiwan Strait depends on the degree of internationalization. Banks’ internationalization might involve additional risks that include external factors such as political risks, economic risks, social risks, and environmental risks, and interior risks such as credit risks and operational risks. Whether high risks are associated with high efficiency needs to be examined by a strict new work. For example, how to exactly measure bank risks is a huge job. Klomp and de Haan (2012) use twenty-five indicators of banking risk, while Berger et al. (2013) use more than a dozen risk variables, to investigate the effects of bank risks resulting from either regulation or internationalization. Among those risk indexes, return on equity, ROA, the Sharpe ratio, nonperforming loans, and the lease loss allowance are the most commonly seen indicators. In our paper, since we mainly focus on the relationship between internationalization and efficiency, we only take into account the risk variables of ROA and nonperforming loans. Therefore, through our empirical results, we can partially see the effect of bank risks on efficiency, 226 Emerging Markets Finance & Trade but it is not a complete work. A complete story about internationalization, risk, and efficiency can be more thoroughly unveiled by a future work. Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 Notes 1. Some research studies also focus on the relationship between bank size and internationalization. “Only a few, large banks have a commercial presence abroad, consistent with the size pecking order documented for manufacturing firms. However, the relationship between internationalization and productivity also yields two inconsistencies with recent trade models. First, virtually all banks hold at least some foreign assets, irrespective of size or productivity. Second, some fairly unproductive banks maintain commercial presences abroad. The size and productivity distributions are dispersed and skewed, and this heterogeneity is mirrored in banks’ internationalization patterns” (Buch et al. 2011). 2. Huang (2010) defines bank efficiency as involving two indexes: (1) the ratio of the number of employees to its total assets and (2) the ratio of a bank’s noninterest expenses to its total revenue (Huang 2010, p. 55). Both indexes differ from the strict definition that appears in the relevant literature on productivity and efficiency. 3. There are K behavior variables (X1, X2, ..., Xk) transformed into an overall index (Y ), where the overall index is a linear combination of behavior variables. Through principal component analysis, if we have K behavior variables, then at most we could get K principal components. We only pick up the principal component whose eigenvalue is greater than 1. 4. Since the duality theorem requires that the cost function must be linearly homogeneous in input prices, we impose the following homogeneity restrictions on the parameters in Equation (1): m ∑β j =1 j m m j =1 j =1 = 1, ∑ βij = 0, ∑ γ ij = 0, i = 1, 2,…, m. Furthermore, the second-order parameters of the cost function in Equation (1) must be symmetric—that is, δnj = δjn, n, j = 1,2,3, γkm = γmk, m,k = 1,2,3. According to Shephard’s lemma, an input share is equal to the derivative of the log cost function with respect to the corresponding log input price. Each input share should lie between zero and unity, and input shares should sum to 1. We define cost shares as follows: Si = 3 3 ∂ ln TC = βi + ∑ γ ij ln Pj + ∑ ρij ln Yn + ηi , m = 1, 2, 3. ∂ ln Pm j =1 n =1 5. Here, Yim is 10 percent of the minimum value of Yi in the sample. Using Yim instead of zero in the equation avoids taking the logarithms of zero in the translog function (Mester 1996). 6. The consumer price index is from the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan, with 2000 as the base year. 7. See Akin et al. (2013) and Chang et al. (2013) for discussion of the relationship between foreign financial institutions of well-diversified currency portfolios and highly effective regulation. References Akin, A.; N. Bayyurt; and S. Zaim. 2013. “Managerial and Technical Inefficiencies of Foreign and Domestic Banks in Turkey During the 2008 Global Crisis.” Emerging Markets Finance & Trade 49, no. 3: 48–63. Allen, L., and A. Rai. 1996. “Operational Efficiency in Banking: An International Comparison.” Journal of Banking and Finance 20, no. 4: 655–672. Altunbas, Y.; M.-H. Liu; P. Molyneux; and R. Seth. 2000. “Efficiency and Risk in Japanese Banking.” Journal of Banking and Finance 24, no. 10: 1605–1628. Banker, R.D.; H. Chang; and R. Cunningham. 2003. “The Public Accounting Industry Production Function.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 35, no. 2: 255–281. Batten, J.A., and P.G. Szilagyi. 2011. “The Recent Internationalization of Japanese Banks.” Japanese Economy 38, no. 1: 81–120. Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 November–December 2014, Volume 50, Supplement 6 227 Battese, G.E., and T.J. Coelli. 1995. “A Model for Technical Inefficiency Effects in a Stochastic Frontier Production Function for Panel Data.” Empirical Economics 20, no. 2: 325–332. Battese, G.E.; D.S.P. Rao; and C.J. O’Donnell. 2004. “A Metafrontier Production Function for Estimation of Technical Efficiencies and Technology Gaps for Firms Operating Under Different Technologies.” Journal of Productivity Analysis 21, no. 1: 91–103. Bayraktar, N., and Y. Wang. 2004. “Foreign Bank Entry, Performance of Domestic Banks and the Sequence of Financial Liberalization.” Policy Research Working Paper Series 3416, The World Bank. ———. 2005. “Foreign Bank Entry and Domestic Banks’ Performance: Evidence Using BankLevel Data.” Penn State University, Harrisburg, and World Bank, Washington, DC. Beck, T.; R. Cull; and A. Jerome. 2005. “Bank Privatization and Performance: Empirical Evidence from Nigeria.” Journal of Banking and Finance 29, nos. 8–9: 2355–2379. Berg, S.A.; F.P. Førsund; and E.S. Jansen. 1992. “Malmquist Indices of Productivity Growth During the Deregulation of Norwegian Banking, 1980–89.” Scandinavian Journal of Economics 94, supp.: S211–S228. Berger, A.N., and R. DeYoung. 1997. “Problem Loans and Cost Efficiency in Commercial Banks.” Journal of Banking and Finance 21, no. 6: 849–870. Berger, A.N., and L.J. Mester. 1997. “Inside the Black Box: What Explains Differences in the Efficiencies of Financial Institutions.” Journal of Banking and Finance 21, no. 7: 895–947. Berger, A.N.; R. DeYoung; H. Genay; and G.F. Udell. 2001. “Globalization of Financial Institutions: Evidence from Cross-Border Banking Performance.” Working Paper no. 1999–25, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Berger, A.N.; S. El Ghoul; O. Guedhami; and R. Roman. 2013. “Bank Internationalization and Risk Taking.” Working Paper, University of South Carolina, 1–54. Buch, C.M.; C.Y. Koch; and M. Koetter. 2011. “Size, Productivity, and International Banking.” Journal of International Economics 85, no. 2: 329–334. Chang, H.-L.; S.-S. Wu; and S.-L. Liao. 2013. “An Analysis of Strategic Equity Stakes Acquisition of Chinese Banks by Foreign Financial Institutions.” Emerging Markets Finance & Trade 49, supp. 3: 98–109. Claessens, S., and T. Glaessner. 1998. “The Internationalization of Financial Services in Asia.” Policy Research Working Paper no. 1911, World Bank, Washington, DC. Claessens, S.; A. Demirgüç-Kunt; and H. Huizinga. 2001. “How Does Foreign Entry Affect Domestic Banking Markets?” Journal of Banking and Finance 25, no. 5: 891–911. Demirgüç-Kunt, A., and H. Huizinga. 1999. “Determinants of Commercial Bank Interest Margins and Profitability: Some International Evidence.” World Bank Economic Review 13, no. 2: 379–408. DeYoung, R., and D.E. Nolle. 1996. “Foreign-Owned Banks in the United States: Earning Market Share or Buying It.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 28, no. 4 (part 1): 622–636. Drake, L., and M.J.B. Hall. 2003. “Efficiency in Japanese Banking: An Empirical Analysis.” Journal of Banking and Finance 27, no. 5: 891–917. Focarelli, D., and A.F. Pozzolo. 2008. “Cross-Border M&As in the Financial Sector: Is Banking Different from Insurance?” Journal of Banking and Finance 32, no. 1: 15–29. Greene, W.H., and D. Segal. 2004. “Profitability and Efficiency in the U.S. Life Insurance Industry.” Journal of Productivity Analysis 21, no. 3: 229–247. Hasan, I., and K. Marton. 2003. “Development and Efficiency of the Banking Sector in a Transitional Economy: Hungarian Experience.” Journal of Banking and Finance 27, no. 12: 2249–2271. Huang, C.J. 2010. “Internationalization and Performance of Taiwanese Banks.” Journal of Business Administration 84, no. 3: 41–70. (In Chinese) Hughes, J.P., and L.J. Mester. 1993. “A Quality and Risk-Adjusted Cost Function for Banks: Evidence on the ‘Too-Big-to-Fail’ Doctrine.” Journal of Productivity Analysis 4, no. 3: 293–315. Klomp, J., and J. de Haan. 2012. “Banking Risk and Regulation: Does One Size Fit All?” Journal of Banking and Finance 36, no. 12: 3197–3212. Lang, G., and P. Welzel. 1999. “Mergers Among German Cooperative Banks: A Panel-Based Stochastic Frontier Analysis.” Small Business Economics 13, no. 4: 273–286. Downloaded by [Chinese Culture University], [Lien-wen Liang] at 17:38 09 April 2015 228 Emerging Markets Finance & Trade Lensink, R., and N. Hermes. 2004. “The Short-term Effects of Foreign Bank Entry on Domestic Bank Behaviour: Does Economic Development Matter?” Journal of Banking and Finance 28, no. 3: 553–568. Levine, R. 1996. “Foreign Banks, Financial Development, and Economic Growth.” In International Financial Markets: Harmonization Versus Competition, ed. C.E. Barfield, pp. 224–254. Washington, DC: AEI Press. Lothian, J.R. 2002. “The Internationalization of Money and Finance and the Globalization of Financial Markets.” Journal of International Money and Finance 21, no. 6: 699–724. Markusen, J.R. 1984. “Multinationals, Multi-Plant Economies, and the Gains from Trade.” Journal of International Economics 16, nos. 3–4: 205–226. Mester, L.J. 1996. “A Study of Bank Efficiency Taking into Account Risk-Preferences.” Journal of Banking and Finance 20, no. 6: 1025–1045. Nolle, D.E. 1995. “Foreign Bank Operations in the United States: Cause for Concern?” In International Finance in the New World Order, ed. H.P. Gray and S.C. Richard, pp. 269–291. London: Pergamon. Outreville, J.F. 2010. “Internationalization, Performance and Volatility: The World’s Largest Financial Groups.” Journal of Financial Services Research 38, nos. 2–3: 115–134. Peek, J., and E.S. Rosengren. 2000. “Implications of the Globalization of the Banking Sector: The Latin American Experience.” New England Economic Review, September/October: 45–62. Peek, J.; E.S. Rosengren; and F. Kasirye. 1999. “The Poor Performance of Foreign Bank Subsidiaries: Were the Problems Acquired or Created?” Journal of Banking and Finance 23, nos. 2–4: 579–604. Porter, M.E. 1990. The Competitive Advantage of Nations. London: Macmillan. Rezvanian, R., and S. Mehdian. 2002. “An Examination of Cost Structure and Production Performance of Commercial Banks in Singapore.” Journal of Banking and Finance 26, no. 1: 79–98. Ruigrok, W., and H. Wagner. 2003. “Internationalization and Performance: An Organizational Learning Perspective.” Management International Review 43, no. 1: 63–83. Sullivan, D. 1994. “Measuring the Degree of Internationalization of a Firm.” Journal of International Business Studies 25, no. 2: 325–342. ul-Haq, R.; J.B. Howcroft; C. Carr; and A. Mullineux. 2012. “Bank Internationalisation, Risk Transference, Risk Management.” European Financial Review April–May: 50–54. Welch, L.S., and R.K. Luostarinen. 1988. “Internationalization: Evolution of a Concept.” Journal of General Management 14, no. 2: 34–55. Yuan, X.M. 2008. “Banking Internationalization: The Choice Between Greenfield Investment and Cross-Border M&As.” In Modern Finance and Global Trading Cooperation: Proceedings of the 5th International Annual Conference on WTO and Financial Engineering, ed. H. Zhang, H. Cheng, and R. Zhao, pp. 74–78. Marrickville, NSW: Orient Academic Forum.

© Copyright 2026