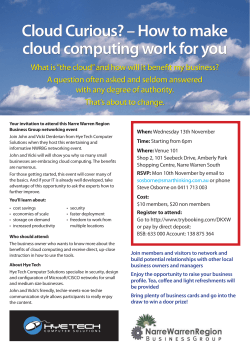

The Black Cloud