Link to Resident Interruption Study Idea

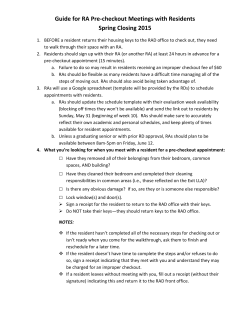

Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 1 Efficiency of Task Switching and Multi-‐tasking: Observations of Pediatric Resident Behaviors when Managing Interruptions to Daily Workflow Jennifer R. Di Rocco, DO Masters Research Seminar Summer 2014 Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 2 Introduction The daily practice of medicine is fraught with frequent interruptions that a busy clinician must manage appropriately in order to ensure the best patient care possible. Tasks that are urgent and time-‐sensitive must be prioritized, organized, and balanced with numerous other tasks requiring completion during the day. Physicians must also maintain the necessary flexibility required to adapt to unexpected events that inevitably surface regularly during a busy clinical workday. The ability to expertly manage interruptions may be considered under the umbrella of the “art of medicine,” which is not found in textbooks and can be difficult to teach. Additional challenges in this era of limited duty hours include limited patient exposure with less time to develop the skills for effective management of interruptions. Some young clinicians seem to easily triage tasks as they are presented, while others struggle with this role. Pediatric residents have graded autonomy as they progress through a program, with a steep learning curve in their first year. From an initial dependence on the senior resident and faculty when starting as a new intern to functioning on their own quite well as they near the start of their second year, each intern matures both clinically and professionally at various rates. The Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has assigned 21 pediatric milestones that must be reported back to them twice yearly with a resident’s progress along the continuum. Milestones describing degree of medical knowledge, trustworthiness, leadership, teamwork and stress management skills are all required and applicable to the topic of one’s ability to manage interruptions appropriately. Carraccio, et al’s (2013) description of the “Patient Care 2” milestone, which reads “Organize and prioritize responsibilities to provide patient care that is safe, effective and Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 3 efficient” addresses the concept of the “optimization of multitasking” in the milestone discussion (p. 9). This is described as a higher level of clinical achievement in which a physician demonstrates concurrent task completion in a manner ends to a more efficient workflow without compromising patient safety (Carraccio, et al, 2013). The complex set of behaviors described by this milestone can be best observed and assessed when a resident has increased responsibility and leadership roles including supervising a team, managing pager calls and admitting new patients simultaneously. Some residents in our program in recent years have struggled in supervisory roles, specifically with this milestone, but some have excelled, despite having less practice than prior decades of trainees. Understanding the factors contributing to how pediatric residents manage interruptions (from novice to “expert”) should be helpful towards designing curricula for mastery of these skills in our program and in others across the nation. Literature Review This literature review will serve to: (a.) discuss different approaches to managing workflow interruptions: multitasking and task-‐switching; (b.) explore some factors that affect how one decides to manage an interruption; and (c.) outline existing work that has been done in direct observations of health care workers’ approaches to managing interruptions, including tools used to analyze the process and behaviors. Approaches to Managing Interruptions: Multitasking and Task-‐Switching First, a review of the structure of a workflow interruption is helpful. Magrabi, Li, Dunn and Coeira (2011) review the literature published in the area of studying interruptions, outlining the types of interruptions that are seen and discussing how these in turn affect the success of task completion, and the difficult extrapolation of how Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 4 interruptions directly affect patient safety and quality of care. The discussion of challenges in directly observing interruptions to workflow and understanding the barriers involved in this practice is very helpful when considering the design of an observational interruption/multitasking/task-‐switching study. The author’s cartoon of the anatomy of an interruption (Figure 1) is a helpful representation of the events involved in task switching, including the interruption and resumption lags in time. |-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐total time-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐| | interruption time | *Start -‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐*interruption lag*-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐*resumption lag*-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐-‐*End primary -‐alert of -‐start -‐end -‐resume primary task (P) interruption I task I task P task task (P) task (I) Figure 1: Anatomy of an Interruption, adapted from Magrabi, Li, Dunn and Coeira 2011, p. 450 The difference between task-‐switching, or turning one’s attention from the current task to a second task presented, and multi-‐tasking, or completing two or more tasks concurrently, is an important distinction when considering how a clinician handles interruptions. Multitasking was historically considered desirable as a means for boosting productivity. It has more recently been described that completing more than one task simultaneously can be detrimental to work efficiency and accuracy (joint tasks not completed as thoroughly) with negative implications for patient safety (Weigl, Muller, Sevdalis and Angerer, 2013). Pashler (2000) describes the differences in these two concepts, and defines the psychological conflicts associated with multitasking. He highlights the slowing in response when an individual attempts to multitask, which is related to one’s ability to process two discrete tasks, select the proper mental “instructions” for each task from a mental queue, and alternate attention between the two tasks as they are attempted simultaneously. He explores the “bottlenecking” mental delay that occurs Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 5 when an individual is faced with multiple tasks, outlining theories for why this may occur; the most compelling of which is a protective mental mechanism in place to prevent important tasks which are already in progress from becoming derailed by new tasks. Regardless of the negative implications of multitasking in the literature recently, multitasking is still being utilized by physicians, and in some areas, it remains a desirable quality. Weigl et al. (2013) describe how the pressures of practicing inpatient medicine in the current health care milieu tend to drive physicians towards practicing this skill at the expense of increased medical errors and less strict infection precaution measures. The authors describe how multitasking is sometimes necessary to manage the volume and complexity of patients that need to be seen in some clinical environments. Physicians in this study which included trainees and supervising physicians were directly observed for multitasking behaviors, then were subjectively assessed on the level of associated strain they were experiencing and completed a self-‐assessment of performance for that day. They found that inpatient physicians spent 21% of their time on multitasking activities overall. The incidence of multitasking did not lead to more strain, and, in fact, led to physicians reporting a higher level of productivity. Those physicians who performed longer multi-‐ tasking activities during the day, however, reported a higher level of mental strain, implying that the executive functioning required for sustained multitasking is quite taxing on one’s psyche. From this body of work, it seems that the duration of multitasking performed is crucial to anticipating its negative effects, rather than the practice of multitasking at all, which may actually be useful in boosting physicians’ self-‐confidence and therefore performance. Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 6 Westbrook et al. (2010) describe a time and motion study that was performed in an emergency department setting to evaluate interruptions to workflow and physicians’ efficiency with tasks, as well as the time cost of completion of primary and interrupting tasks. An interesting and unexpected result of observed task-‐switching behaviors was that if Task A were interrupted by Task B, the total time for the original Task A completion was often half the time it would take the provider to complete the task had it not been interrupted. This was explained by a faster work rate to make up time or shortcuts taken when returning to the original task, with the quality of task completion in a shorter timeframe not addressed. Nearly 20% of all observed interrupted tasks were never completed, compared with 1.5% of uninterrupted tasks being unfinished. The implications for patient care are significant if 1 out of every 5 tasks interrupted leads to an incomplete outcome. The authors note how important it is to develop processes and continue education in maximizing understanding of interruptions, how to manage them, and how to minimize dangerous or careless multitasking or task switching that can have adverse effects on patient safety/medical errors. Factors Contributing to the Management of Interruptions Outside of the medical literature, Weaver and Arrington (2013) describe original experiments that probe the characteristics of task-‐completing behaviors when participants group tasks together in their mind in a hierarchical manner. In this psychological experiment, the authors explore one’s mental representation of the steps required to complete a task and how that affects a participant’s ability to switch between tasks. Participants were able to perform tasks more quickly that were within the same mental hierarchy, and were able to switch between these tasks more quickly than those that were Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 7 in a separate group within their mental model. Practically speaking, this hierarchy concept could be modeled as one group of tasks being those that require reading/writing skills (i.e. composing notes on a computer screen, interrupted to write an excuse letter for a patient being discharged) and another group of tasks being those that require kinesthetic skills (i.e. examining an asthmatic patient prior to the next Albuterol administration, interrupted by needing to examine a patient having a reaction to a blood transfusion). This paper would argue that it is much easier/more efficient to task-‐switch within groups than between groups as a different mental skill set must be accessed for the latter. Through their experiments, the authors discuss theories of how creating mental hierarchies can be protective towards achieving a goal in being directed with one’s actions within a task set and rejecting competing actions or interruptions that are not congruent with the overarching goal. This paper outlines the psychological theory and structure of human behavior when faced with multiple tasks arriving at once (such as those presented simultaneously on a busy medical ward), and could help inform a discussion when analyzing resident’s behaviors. Another factor affecting one’s ability to manage interruptions safely (and also complete tasks safely without interruption) is the degree of fatigue a provider is operating under in a health care setting. With the ever-‐changing resident duty hour restrictions, much attention has been drawn to resident performance as related to the amount of sleep debt they have accumulated. A study was performed in residents analyzing the effects of sleep deprivation and sleep recovery on the executive functioning required for task-‐ switching, and found that both the accuracy and speed of performing interrupting tasks Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 8 were adversely affected by sleep deprivation, but these effects were reversed with one night of recovery sleep (Couyoumdjain et al., 2010). The innate ability to multitask well can also contribute to how one manages an interruption. Ledrick, Fisher, Thompson and Sniadanko (2009) assessed emergency department providers’ multitasking aptitude through a commercially available computerized tool. The Multi-‐Tasking Assessment Tool (MTAT), which has been used in other professions requiring attention to more than one task at a time, was utilized within the medical realm with hopes to spur further research and possible tool development in this area. Emergency medicine residents were administered this tool and their score was then assessed by its relation to their success in multitasking on the job, as measured by their productivity (RVUs generated). One can argue that such a tool may be helpful in selecting physicians who have optimized multitasking. The residents were controlled by the variables of PGY year as well as intelligence as rated by their yearly in-‐training exam scores, and the authors felt the tool was able to analyze a resident’s ability to multitask independent of PGY year or medical knowledge. A multiple regression model showed that 87% of variance in productivity could be predicted by PGY year (the more experience residents had, the more effective they were) and 13% predicted by MTAT score alone. Therefore, the argument that this sort of tool could be useful in providing feedback with implications for recruitment processes seems sound. Interestingly, Weigl et al. (2013) found that inpatient ward physicians spent as much time multitasking as did the emergency department physicians, who had in past literature lead the way for multitasking behaviors in medicine. As young physicians in many residencies may work in both emergency department and ward settings, these skills Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 9 may be desirable across many clinical arenas, and a tool such as the MTAT may be useful to determine these characteristics prior to matriculation into residency, or as a tool to aid those struggling to manage multiple tasks. The MTAT does not discern between multitasking and task-‐switching, however, and it is not clear if this tool may help to identify some features of being well-‐equipped for both strategies. Methods for Observing Interruption Handling Behaviors Many of the current papers in the multitasking/task switching literature have outlined organizing structures and tools used to directly observe health care providers on the job to record their manner of dealing with interruptions in their clinical workflow, some of which could translate well to future observational studies. Weigl et al. (2013) describe the logistics of performing direct observations of physician performance through using an established tool which partitions 36 identified tasks into the four categories of direct patient contact, indirect patient contact, professional and personal activities. Trained observers recorded each instance of multitasking when one of these tasks occurred at the same time as another. Brixey, et al. (2007) categorized methods for naming tasks and task hierarchies as they pertain to a clinical workflow by direct observation of physicians and nurses. The process the authors describe in developing a list of both deductive and inductive tasks performed by nurses and physicians and then categorizing these tasks in “superordinate,” “basic” or “subordinate” tiers so as to better classify the task performed is helpful when considering the design of an observational tool for studying pediatric residents’ behaviors when dealing with interruptions. Hanauer et al (2012) contributed a user-‐friendly direct observation tool modified from one provided by the Agency for Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 10 Healthcare Research and Quality that has been validated in previous studies. This would prove useful for the observation of pediatric residents. Sitterding, Ebright, Broome, Patterson and Wuchner (2014) provide clear examples of how nurses have utilized education and systems processes to minimize and manage interruptions safely during medication administration, a necessarily critical time in patient care. Situational awareness and cognitive task analysis are discussed as important factors in this culture of patient medication safety. In this paper, interruptions to nurse workflow were observed and categorized into visual, auditory and interrupting thought cues. Interruption handling strategies the nurses employed were classified as blocking (triaging and then deciding not to deal with the interruption at that moment), engaging (task-‐ switching away from current task to focus all mental energy on the interruption), multi-‐ tasking (dealing with the interruption task at the same time as continuing the primary task) or mediating (asking others to deal with the content of the interruption). The general themes outlined in this paper are applicable to physicians and may have helpful implications for curricular development in training young physicians how to appropriately manage interruptions to the clinical workflow. Summary Many factors are involved in how physicians manage interruptions, and the positive or negative effects of their management decisions have implications on patient safety and medical errors in the clinical workplace. Observational studies of pediatric residents do not exist in the current literature, nor does a study exist that correlates physicians’ ability and quality of interruption management with their overall wellness including their preferred learning styles, aptitudes in dealing with interruptions, sleep debt, and mental Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 11 strain. Garnering such data and analyzing such variables could provide added guidance and understanding to those residency programs that are struggling to help learners improve in this arena, which is difficult to truly assess until a resident is in a supervisory position with multifactorial responsibilities. If there were a way of predicting aptitude in this skill set early, learners who may not easily manage interruptions could be targeted and practice exercises designed to strengthen this skill set. With this intervention, the transition from an intern to a senior supervising resident may be much smoother. The first step towards creating tools for augmenting performance in the area of managing interruptions gracefully and efficiently is to understand the current factors that are involved in a resident’s decision process when faced with interruptions during the daily workflow. An observational study of residents in real time would provide such data and serve as a springboard for future work in creating tools and curricula to assist residents struggling with task management. Methods Subjects Internal Review Board approval from the University of Hawaii will be attained prior to recruitment, and residents in the University of Hawaii Pediatrics Residency Program will be recruited and consented to participate in this study. The maximum number of residents who may participate would be 22, as we currently have eight PGY-‐1 residents, seven PGY-‐2 residents and seven PGY-‐3 residents (there may also be added potential for up to five additional recent graduates being observed during their first year as an attending in our hospital). Inclusion criteria are being a pediatric resident or pediatric residency graduate in the last year. Exclusion criterion is resident choice not to participate. Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 12 Setting This study will take place at the main hospital affiliate for the University of Hawaii Pediatric Residency Program, Kapi’olani Medical Center for Women and Children in Honolulu, Hawaii. This is the sole pediatric tertiary care center for all the Hawaiian islands and a 500 mile radius of the Pacific Basin. Each resident will be observed while rotating on the general pediatric wards only, in either an intern or supervisory role, depending on level of training. Both day shifts and night shifts on the wards will be observed. Data Sources and Measures Baseline Survey. Each recruited resident will complete a baseline survey administered online through a publically available tool (www.surveymonkey.com). The survey will include demographics, questions about perceptions of personal wellness, sleep patterns and self-‐rating of how well one manages interruptions (Appendix A). Learning Style Inventory. Each recruited resident will complete an online learning style inventory available to those in educational programs (www.vark-‐learn.com) prior to being observed. This inventory explores preferred categories of learning methods including visual, auditory, read/write and kinesthetic and scores participants in each area (Appendix B). The final screen gives a composite score across the four learning styles, and a summary of each style is provided to the participant for review. Multi-‐Tasking Assessment Tool. Following procurement of a small grant, enough MTAT tools will be purchased so that all participants can be assessed. Each participant will be given instructions and a password to take the MTAT (www.multitaskingtests.com) online (Appendix C for sample screen, see website for demo of actual interactive tool). Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 13 Mental Strain Surveys. After each of the two observation periods, each participant will complete the validated NASA Task Load Index (Hart, et. al, 1988) that inquires about mental strain and performance during that particular workday that was being observed (Appendix D). This is the same strain tool used in an abridged version in Weigl et al (2013). Direct Observation Tool. The time and motion tool referenced in Hanauer et al (2013) will be utilized for observing the participants (Appendix E for screenshot of interactive tool) and categorizing the nature of interruptions and participant behaviors in relation to these interruptions. Data Collection Procedures Each recruited resident will be asked to complete the baseline survey, learning style inventory and MTAT online; the VARK and MTAT results will need to be printed and turned in to the study coordinator. The results of these three items will be de-‐identified to the observer with each document assigned a randomly generated number that is unique to that resident. The program administrator will manage hard copies of these documents and maintain the unique identifiers in a locked cabinet blinded to the study leader (and trained observers if available). Each resident will then be observed by the study leader (and/or trained observers with testing to prove inter-‐rater reliability if funding/manpower available for this) for 2-‐hour periods at separate intervals during a scheduled shift on the pediatric wards. These observations will occur throughout the year, as each resident rotates through the general wards, with the goal of two observations each. The timeframe for study completion is one calendar year. This will be a time and motion study, which describes the continuous observation of a participant’s workflow while noting the time it takes for task completion and all the actual steps/motions the participant performs in Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 14 completing those tasks. The established physician task division tool as described and used by Hanauer, et al. (2013) will be utilized. Each resident’s behaviors and time to perform those behaviors will be recorded by the study leader using a password protected, portable tablet computer that will be securely locked in the study coordinator’s office when not in use. Each resident will complete a short questionnaire at the end of each observational session, rating his or her mental strain that day. The program administrator will de-‐ identify and code observation sheets and mental strain surveys to be matched to the participants’ initial documents. Incentives for residents who participate will be their choice of a $20 Starbucks or iTunes gift card pending grant approval. Data Analysis Participant data gathered from the baseline surveys will be summarized using descriptive statistics. Following the data gathering during the observations, the resident’s average time for interruption management will be calculated. A linear regression will be performed to look for correlations between certain factors (including sleep, wellness, stress, learning style, MTAT score, PGY year) and time management of interruptions (task-‐ switching and multitasking). Research Question 1: Can pediatric resident management of interruptions including time spent and effective completion of tasks when there are interruptions to their clinical workflow be predicted by their MTAT score? Hypothesis: The MTAT score will predict the most efficient residents, as defined by taking the least amount of time to manage interruptions and effectively triaging tasks as they arise. This is a quantitative design as the resident behaviors will be quantified by an average time for response to interruptions and completing all tasks. The resident’s MTAT score will be Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 15 compared to his or her average time and predominant method of responding to interruptions. The independent variable will be the MTAT score which is calculated an automated program and serves as a composite score of overall multitasking effectiveness. The dependent variable is the average time for dealing with the interruption. A linear regression analysis will be performed to assess degree of correlation between these variables. An important issue is the observer being blinded to the MTAT score so as not to skew interpretation of behaviors when answering this research question. Research Question 2: Do senior level pediatric residents manage interruptions more efficiently than interns? Hypothesis: Yes, overall PGY3 residents will manage interruptions more efficiently than PGY1 residents. This is a mixed methods study in that the average means for senior level residents (n=7 at the most) will be compared to that of interns (n=8 at the most) using the t-‐test to determine if differences exist between the mean time for PGY3 residents and PGY1 residents to manage interruptions in the same three categories of phone calls/pages, people and patient interruptions. Research Question 3: Do personal wellness and sleep debt affect task-‐switching efficiency? Hypothesis: Yes, low wellness scores and high sleep debt together negatively impact task-‐ switching efficiency. This is a quantitative study that explores the participant’s self-‐perception of their own wellness variables and self-‐reported hours of sleep. A chi-‐squared test will be applied in this case to assess the categorical variables of gender and self-‐rated effectiveness with interruption management and correlation with efficiency in task-‐switching. ANOVA will be Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 16 performed to analyze correlation of efficient task-‐switching with the numerical average of hours slept per night and numerical wellness score, both alone and considered together. The independent variables will be the data reported by participants, and the dependent variable being the observed, timed behaviors. Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 17 References Brixey, JJ, Robinson, DJ, Johnson, CW, Johnson, TR, Turley, JP, Patel, VL &Zhang, J. (2007).Toward a hybrid method to categorize interruptions and activities in healthcare.International Journal of Medical Informatics, 76,812-‐820. Carraccio, C., Benson, B., Burke, A., Englander, R., Guralnick, S., Hicks, P., Ludwig, S., Schumacher, D. &Vasilias, J. (2013). Pediatrics Milestones.Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 5, No. 1s1, pp. 59-‐73 Couyoumdjain, A, Sdoia, S, Tempesta, D, Curcio, G, Rastellini, E, De Gennaro, L. & Ferrara, M (2010).The Effects of Sleep and Sleep Deprivation on Task-‐Switching Performance. Journal of Sleep Research, 19, 64-‐70. Hanauer, D, Zheng, K, Commiskey, E, Duck, M, Choi, S & Blayney, D (2013). Computerized Prescriber Order Entry Implementation in a Physician Assistant-‐Managed Hematology and Oncology Inpatient Service: Effects on Workflow and Task Switching. Journal of Oncology Practice, 9, 4: e103-‐114. Hart SG, Staveland LE, Hancock PA, et al (1988). Development of NASA-‐TLX (Task Load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. Human mental workload. Oxford, UK:North-‐Holland. 139Y183. Ledrick, D, Fisher, S, Thompson, J and Sniadanko, M (2009). An Assessment of Emergency Medicine Residents’ Ability to Perform in a Multitasking Environment.Academic Medicine, 84, 9: 1289-‐1294. Magrabi F., Li, S.Y.W., Dunn A.G. &Coeira, E. (2011).Challenges in Measuring the Impact of Interruption of Patient Safety and Workflow Outcomes.Methods of Information in Medicine, 50,447-‐453. Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 18 Pashler, H. (2000). Task Switching and Multitask Performance. In Monsell S, Driver, J (eds) Attention and Performance XVIII:Control of Cognitive Processes,277-‐307. Location: Bradford, Cambridge, MA. Sitterding, M.C, Ebright, P., Broome, M., Patterson, E.S. &Wuchner, S. (2014). Situation Awareness and Interruption Handling During Medication Administration.Western Journal of Nursing Research, 1-‐26. Weaver, S.M. &Arrington, C.M (2013). The Effect of Hierarchical Task Representations on Task Selection in Voluntary Task Switching.Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition,39,4:1128-‐1141. Weigl, M., Muller, A., Sevdalis, N. &Angerer, P (2013).Relationships of Multitasking, Physicians’ Strain, and Performance: An Observational Study in Ward Physicians. Journal of Patient Safety, 9, 18-‐23. Westbrook, J.I., Coiera, E., Dunsmuir, W.T., Brown, B.M., Kelk, N., Paoloni, R. & Tran, C (2010).The impact of interruptions on clinical task completion.Quality and Safety in Health Care, 19,284-‐289. Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 19 Appendix A Baseline Survey for Interruption Study 1 2 3 (circle one) 1. I am a PGY 2. I am a male female 3. I would rate my ability to manage interruptions effectively and efficiently during my clinical time on the wards as Poor Suboptimal Neutral Good Excellent What do you think might help you improve in this area? (free text) 4. Over the past week, I have gotten this many hours of sleep each night (write in hours slept each night, to the best of your ability to remember): M Tu W Th Fri S S This was a typical week for me TRUE FALSE 5. A person’s wellness can be measured in many ways, including physical health, mental health, amount of regular exercise, quality of relationships and balance across many facets of life. On a scale of 1-‐10, with 10 being the top score for wellness, how would you rate yourself, taking these factors into account? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 20 Appendix B The VARK Questionnaire (Version 7.8) How Do I Learn Best? Choose the answer which best explains your preference and circle the letter(s) next to it. Please circle more than one if a single answer does not match your perception. Leave blank any question that does not apply. 1. You are helping someone who wants to go to your airport, the center of town or railway station. You would: a. b. c. d. go with her. tell her the directions. write down the directions. draw, or show her a map, or give her a map. 2. A website has a video showing how to make a special graph. There is a person speaking, some lists and words describing what to do and some diagrams. You would learn most from: a. b. c. d. seeing the diagrams. listening. reading the words. watching the actions. 3. You are planning a vacation for a group. You want some feedback from them about the plan. You would: a. b. c. d. describe some of the highlights they will experience. use a map to show them the places. give them a copy of the printed itinerary. phone, text or email them. 4. You are going to cook something as a special treat. You would: a. b. c. d. cook something you know without the need for instructions. ask friends for suggestions. look on the Internet or in some cookbooks for ideas from the pictures. use a good recipe. 5. A group of tourists want to learn about the parks or wildlife reserves in your area. You would: a. b. c. d. talk about, or arrange a talk for them about parks or wildlife reserves. show them maps and internet pictures. take them to a park or wildlife reserve and walk with them. give them a book or pamphlets about the parks or wildlife reserves. 6. You are about to purchase a digital camera or mobile phone. Other than price, what would most influence your decision? a. b. c. d. Trying or testing it. Reading the details or checking its features online. It is a modern design and looks good. The salesperson telling me about its features. 7. Remember a time when you learned how to do something new. Avoid choosing a physical skill, eg. riding a bike. You learned best by: a. b. c. d. watching a demonstration. listening to somebody explaining it and asking questions. diagrams, maps, and charts - visual clues. written instructions ± e.g. a manual or book. From www.vark-‐learn.com Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 21 8. You have a problem with your heart. You would prefer that the doctor: a. b. c. d. gave you a something to read to explain what was wrong. used a plastic model to show what was wrong. described what was wrong. showed you a diagram of what was wrong. 9. You want to learn a new program, skill or game on a computer. You would: a. b. c. d. read the written instructions that came with the program. talk with people who know about the program. use the controls or keyboard. follow the diagrams in the book that came with it. 10. I like websites that have: a. b. c. d. things I can click on, shift or try. interesting design and visual features. interesting written descriptions, lists and explanations. audio channels where I can hear music, radio programs or interviews. 11. Other than price, what would most influence your decision to buy a new non-fiction book? a. b. c. d. The way it looks is appealing. Quickly reading parts of it. A friend talks about it and recommends it. It has real-life stories, experiences and examples. 12. You are using a book, CD or website to learn how to take photos with your new digital camera. You would like to have: a. b. c. d. a chance to ask questions and talk about the camera and its features. clear written instructions with lists and bullet points about what to do. diagrams showing the camera and what each part does. many examples of good and poor photos and how to improve them. 13. Do you prefer a teacher or a presenter who uses: a. b. c. d. demonstrations, models or practical sessions. question and answer, talk, group discussion, or guest speakers. handouts, books, or readings. diagrams, charts or graphs. 14. You have finished a competition or test and would like some feedback. You would like to have feedback: a. b. c. d. using examples from what you have done. using a written description of your results. from somebody who talks it through with you. using graphs showing what you had achieved. 15. You are going to choose food at a restaurant or cafe. You would: a. b. c. d. choose something that you have had there before. listen to the waiter or ask friends to recommend choices. choose from the descriptions in the menu. look at what others are eating or look at pictures of each dish. 16. You have to make an important speech at a conference or special occasion. You would: a. b. c. d. make diagrams or get graphs to help explain things. write a few key words and practice saying your speech over and over. write out your speech and learn from reading it over several times. gather many examples and stories to make the talk real and practical. Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 22 The VARK Questionnaire Scoring Chart Use the following scoring chart to find the VARK category that each of your answers corresponds to. Circle the letters that correspond to your answers e.g. If you answered b and c for question 3, circle V and R in the question 3 row. Question a category 3 K b category c category d category V R A b category c category d category Scoring Chart Question a category 1 K A R V 2 V A R K 3 K V R A 4 K A V R 5 A V K R 6 K R V A 7 K A V R 8 R K A V 9 R A K V 10 K V R A 11 V R A K 12 A R V K 13 K A R V 14 K R A V 15 K A R V 16 V A R K Calculating your scores Count the number of each of the VARK letters you have circled to get your score for each VARK category. Vs circled = As circled = Total number of Rs circled = Total number of Ks circled = Total number of Total number of Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 23 Appendix C From www.multitaskingtests.com Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 24 Appendix D Figure 8.6 NASA Task Load Index Hart and Staveland’s NASA Task Load Index (TLX) method assesses work load on five 7-point scales. Increments of high, medium and low estimates for each point result in 21 gradations on the scales. Name Mental Demand Very Low Physical Demand Very Low Temporal Demand Very Low Performance Perfect Effort Very Low Frustration Very Low Task Date How mentally demanding was the task? Very High How physically demanding was the task? Very High How hurried or rushed was the pace of the task? Very High How successful were you in accomplishing what you were asked to do? Failure How hard did you have to work to accomplish your level of performance? Very High How insecure, discouraged, irritated, stressed, and annoyed wereyou? Very High From Hart, et. al (1988) Pediatric Resident Management of Interruptions 25 Appendix E From Hanauer, et al (2013, p. e114)

© Copyright 2026