Extended Chaos and Disappearance of KAM Trajectories

Physica 13D (1984) 82-89

North-Holland, Amsterdam

E X T E N D E D C H A O S A N D D I S A P P E A R A N C E OF KAM T R A J E C T O R I E S

David B E N S I M O N and Leo P. K A D A N O F F

The James Franck Institute, University of Chicago, 5640 S. Ellis, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

R e c e i v e d 26 O c t o b e r 1983

In two-dimensional area-preserving maps, KAM trajectories serve as natural boundaries between stochastic regions. As

they disappear, points may leak out from one region to the next. This escape rate is defined and related to the action-generating

function. Analytic and numerical results are presented to describe the behavior of the escape rate near the disappearance of a

KAM trajectory.

I. Introduction

The study of area-preserving maps in two dimensions is motivated by the fact that these maps

exhibit the non-trivial dynamics of the simplest

class of conservative systems (e.g., Hamiltonian

systems with two degrees of freedom). In these

mapping problems a sequence of points X / = (5, 0/)

j = 0,1, 2 . . . . is generated by the mapping function

T via Xj + 1 = T(Xj). We assume that the mapping

is continuous and invertible so that we can study

the behavior of the entire sequence Xj ( j = 0,

+ 1, + 2 . . . . ). Depending upon the initial point,

X 0, these sequences m a y show several different

behaviors including:

Cyclic. The sequence repeats with period q: Xj+q

=Xj.

Invariant (KAM) curve. The sequence never

repeats but the points X/ fill out a curve F. That

is, for each x on F, we can find a subsequence Xjo

of Xj such that

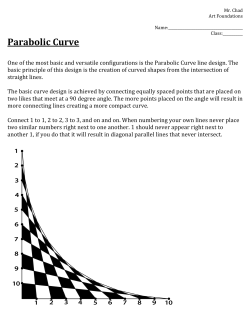

These different orbits are exhibited in fig. 1.

Notice that if a K A M curve F encloses a region

R r containing a fixed point X* of T (i.e., T(X*)

= X*), then

Vx~Rr, n~Z:

In words: chaos cannot move across K A M curves.

If the mapping T depends upon some parameter

k, as for example, the standard m a p Tk,

(r,O)~(r',O')=

1.0 L

'

J

'

I

'

0.6 ~--

,

I

'

J

'

~ _

+

o

o 2~-

+

o

~ , .

,..,~"

R "

"¢~~..:

-0.2 ;..~,-"c~'~'~"~"

n

It is also believed that for some starting points,

{Xj} shows an area-filling chaotic behavior,

namely:

Chaos. There exists a region R c of finite area

such that if x lies anywhere in R c there is a

subsequence XA which approaches x.

r-~-~-sin2~r0, r'+0

(1.1)

lim Xj = x .

r/...~ O0

T " ( x ) ~ R r.

....

-

~

-0.4

-I.0

0

,

I

0.2

,

I

0.4

,

I

0.6

,

I

0.8

,

1.0

THETA

Fig. 1. Three typical orbits of an area preserving map: the

standard map at k = k c. a) Periodic orbit; b) K A M trajectory;

c) bounded chaotic orbit.

0167-2789/84/$03.00 © Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.

(North-Holland Physics Publishing Division)

D. Bensimon and LP. Kadanoff/ Extended chaos and disappearance of KAM trajectories

then as k is varied and reaches some critical initial

value k c, a K A M curve may disappear, i.e., become discontinuous, Cantor set like. In that case a

barrier to the extension of chaos vanishes and the

chaotic region may thus suddenly grow in size. It

is the purpose of this paper to understand what

may happen in this sudden growth. Many of the

results of the present paper were obtained in parallel by MacKay, Meiss and Percival with whom we

had fruitful exchanges [1].

2. The escape rate from a chaotic region

Notice that a KAM curve bounds an invariant

region: If R r contains a fixed point and if F is a

K A M curve, the function Tk maps R r into itself:

Tk( Rr)= Rr .

being a K A M curve. In parallel, we can define an

escape rate for any region as

E(Tk, R) =

L(Tk,R)

~2(R)

(2.5)

This escape rate serves as a bound on the rate at

which points may leak out of R. Notice that if we

apply q steps of Tk we have

L(Tq, R)<-qL(Tk,R),

(2.6)

so that the number of steps Q required to reduce

the area in TkQ(R)nR to a proportion O of the

original area I2(R) is bounded by

1-O

Q> e(rk,R)"

(2.7)

(2.1)

Once the K A M curve has disappeared there exists

no invariant region corresponding to R r. If we

look for such a region Rv, bounded by a y which

is a closed curve but not a KAM curve, then

Tk(Rv) 4: R v.

(2.2)

If Rv contains a fixed point then the region Tg(Rv)

will partially overlap with Rv,

(2.3)

Here ~2(Rv) is just the area of region Rv. As k

approaches the critical value and R v approaches

Rr, for F being the critical KAM curve, then the

region of overlap will get closer and closer to the

entire region R r and the left-hand inequality in

eq. (2.3) will get closer and closer to an equality.

In this limit we can say that the area escaping

from Rr,

L(T , R,) =

83

n E - R,)

(2.4)

(where E - Rr is the complement of Rv), goes to

zero.

Eq. (2.4) represents the leakiness of the curve "t

under the mapping Tk. This leakiness is zero for -f

Hence to get the best possible bounds on the

permitted motion we should wish to minimize the

escape rate (2.5). For this reason we consider, in

this paper, the construction of the minimum escape

rate from a given region [2].

Imagine that we wish to look for the escape

from some region R 1 into another disjoint region

R 2. Then consider all regions Rv containing R 1

( R r ~ R1) and not overlapping R 2 ( R v c E - R2).

Under these constraints we define t h e m i n i m u m

escape rate from a neighborhood of R 1 into a

neighborhood of R 2 to be

e( Tk, R1, R2) = i n f [ E ( T k , R , ) ] ,

(2.8)

with the minimum (inf) being taken over all Rv

which satisfy the constraints.

Since we are interested in the case in which

L(Tk, R) may be very small, we also calculate the

slightly simpler minimum escaping area

l(T k, R1, R 2) = inf[ L ( T k, R,)].

(2.9)

We expect that the Rv's which give the minimum

in (2.8) and (2.9) are essentially identical.

Given these definitions, we set out to estimate e

and l. To begin, we approximate a curve which is

"almost" the K A M curve by constructing one

84

D. Bensimon and L.P. Kadanoff/ Extended chaos and disappearance of KA M trajectories

which goes through all the elements of cycles

which approximate the KAM curve. This construction is meaningful even after the KAM curve

has disappeared. We note that this curve gives an

extremal of l: moving away from the unstable

cycle elements increases / while moving away from

the stable cycle elements decreases 1 (see appendix

A). This extremum does give a bound on l, which

can be estimated with the aid of a scaling theory

for near critical K A M curves. Then we look at

obtaining a better bound by considering curves

which pass only through elements of an unstable

cycle.

1.2

'

I

'

i

I

i

[

i

.... r+lTl rlTIT] I]ITI]-I

1.0

0.8

0.6

R

0.4

0.2

0

-0.2

I

0.2

0

0.4

I

I

0.6

i

I

0.8

,

1.0

THETA

Fig. 2. The escaped area (dashed region) for a trivial test

region: the square (0 _<r < 1; 0 _<8 < 1).

3. Bounding the escape rate by cycles

For specificity, we concern ourselves with the

mapping (1.1) defined on a cylinder, i.e., with

0 = O + 1, and consider the K A M trajectory with

winding number W = (~/5 + 1)/2, which disappears at k = k c = 0.97163540 . . . . This curve is

shown in fig. 1.

The initial regions (R 1 and R2) are chosen to lie

between two K A M curves by taking Rx to be a

narrow strip around r = 1/2, while R 2 includes

similar strips about r = + 3/2. We consider the

test region Rv to be the area bounded by the

curves Y0 and ~/1, where ~'0 is defined parametrically by writing

Yo:

O=O(t),

r=r(t),

0_<t<l,

with

0(0) = 0(1) + 1 ,

O's in [0,1]. Then the bounding curves are (see

fig. 2)

Y0:

r(t) =0,

O(t) = t;

o(t)=t,

while the images of these curves are

k

2~r sin2rrt,

k

O'(t) = t - ~ sinZlrt,

r'(t) =

T(yo):

and T(3q) is the same curve displaced one step

upward. Since the area enclosed by Y0 and 7t is

one, the escape rate and the escaping area are

identical and given by

E(Tk,Rv)=

O=O(t),

r=r(t)+

(3.2)

r(0) = r(1),

and "tl is defined as the same curve displaced one

step upward:

Yt"

(3.1)

r ( t ) = 1,

l.

A trivial estimate of the escape rate will be

obtained if we choose Rv to include all r ' s and

L(Tk,Rr)

- - ~Ikl

.

(3.3)

Notice that for k = k c this trivial estimate gives

roughly 10% of the area escaping upon one iteration.

It is instructive to obtain the result (3.3) in

another way. Notice that the curves Y0 and its

image T(Y0) pass through the stable fixed point at

(r, 0) -- (0,0) and the unstable fixed point at (r, 0)

D. Bensimon and LP. Kadanoff / Extended chaos and disappearance of KAM trajectories

= (0, ½). The escaped area is

o.,ok

½L(Tk,Rr)=Sol/2r(t)~dt

0"f/

Lv

e1/2

, dO'(t)

-Jo r ' ( t ) ~ d t .

(3.4)

Remark that the motion is generated by an action

principle in which

r'(t)=

r(t)=

a A(O,O') o-or)

} '

aO'

0 ' = 0 (t)

O---~A(O,O')o=o(t)

\

<°' t

0.501

\

,

0

-

/1

'\, x-o'x-,~-'x / ,dI

I

0.4

0.8

THETA

1

'

I

'

I

'

I

0.71

,

0.70

O'=O'(t)

with

0.69

A(0,0') = -½(0-0') 2--(2,r) 2 cos2rr0.

Thus,

'

o.p

0.72

(3.5)

85

(3.6)

0.68

0.2

0.4

0.3

0.5

THETA

L(Tk, Rr) is given by

Fig. 3. a) A curve "t (full line) and its image y ' = Tk(-t )

(dashed line), passing through all stable (0) and unstable (x)

elements of the p / q = 5 / 8 cycle; b) segment of the above

curves lying in (0.68 < r < 0.72; 0.2 < 0 _< 0.55). The escaped

area is the dashed region.

L(Tk,RT)=2fol/2(dO

0

dt 00

dO O) A(O,O')dt.

dt' 00"

+----

Since the integrand is a total derivative, we find

L(Tk, Rv)=2(Au-As).

(3.7)

Here A u =A(½, ½) is the action for the unstable

cycle while A s = A(0,0) is the action for the stable

one. Notice that in the derivation of eq. (3.7) we

have used no properties of the paths 70 and 71

except the facts that they cross their image paths

"/~ = T(70) and "/~= T(71) at only the cycle points.

Hence, the results (3.7) and (3.3) hold for all paths

which pass through the fixed points and have no

other crossing points. This result is thus extremal

(indeed constant!) under variations of the paths.

This result may be immediately generalized to

higher order cycles. Let "/o pass through the 2q

dements of a stable and unstable cycle of length q

as in fig. 3. Let the image path cross the original

path only at these 2q points. The stable cycle has

0-values 87 and the unstable one 0-values 0p. Then

the escaped area is the union of the shaded regions

shown. The net result is a form for L which is

L(Tg'Rv)= 2E f 0ui' rdO- fo;ur'dO'.

JvO;

m

By exactly the same calculation as before, we can

reduce the result to

L(Tk, Rv) = 2(Aqu -

a qs),

(3.8)

where A q and A q are the total actions for the

stable and unstable cycles of length q, namely

q-l{

Aq= E -½(#j"-Oj~-i

j=o

)2

}

---c°s2*r~

(2Ir) 2

(a = u,s).

~

(3.9)

D. Bensimon and L.P. Kadanoff/ Extended chaos and disappearanceof KA M trajectories

86

This result is, once again, path independent so

long as the original path considered, To passes

through the cycle elements and crosses its image

path at these points only. This approach yields a

sequence of estimates for L(T, R) and E(T, R),

by choosing a succession of cycles converging to

the K A M curve (or Cantor set for k > kc). For the

Golden mean (W = (v~- + 1)/2) these cycles are of

period [3] q. = F., where F. is the n th Fibonacci

number, and have Oj+q, = ~ + p , , with p, = F n _ 1.

For k < k c, the leakage rate Lq.(Tk, R) goes to

zero faster than exponentially [4]. For k = k c,

zq"(Tk, R) "') 0 algebraically in q~ [5, 6, 7]. In fact

from the scaling and renormalization group analysis [5, 6, 7] of the action for the Golden mean

K A M curve near its disappearance, we expect that

Lq"(Tk, R ) = qZ(~°+Y°)L*~

(q, l k -

QI~),

(3,10)

with: d o = x o + Y0 = 3.049960... ; I, = 0.987463...

and where L ~ ( ~ ) is a scaling function which

applies respectively when k > k¢ or k < k¢. Its

exponential behavior (~ ~ oo) is

k < kc:

L* ( ~ ) - e - ~

k>kc:

L * ( ~ ) - ~ do.

(T a constant),

(3.11)

Namely, in the supercritical case we expect

lim zq"(Tk,

qn"-) oO

R) =

I~ -

kcl "d°-

(3.12)

However, the region k > k¢ is not directly accessible to this analysis since the "stable" cycles tend

to bifurcate and increase in number as k passes

above k c. Hence, we seek a formulation based

only upon unstable cycles.

There is another reason for looking to the unstable cycles. If we move our curve "t slightly from

the unstable cycle elements, L(T k, Rv) increases

at a rate proportional to the separation squared

(appendix A). But a corresponding motion away

from the stable cycle elements decreases L (Tk , R v ).

Since we are looking for a minimum of the escape

rate we should seek to get away from the stable

t

l

1/

f

I

/

I

I

I

I

I

.C?"

I

/

/

I

I

I

~

I

o.~

I

I

x.,.

I \1-'

Fig. 4. The escaped area (dashed region) for a curve V passing

through unstable cycle elements only. A and C are neighboring

points of the unstable cycle; B and B' are homoclinic points.

elements, and use a curve which passes through

unstable elements only.

4. Numerical results using unstable cycles only

The curve T passing through all the elements of

an unstable cycle is generated in the following way

(see fig. 4). Choose two neighboring points A and

C of an unstable cycle with winding number W =

p / q ~ F,_I/F.. The curve y between these two

points is composed of the unstable manifold of A

and the stable manifold of C which intersect at the

homoclinic point B*. Iterating that segment (ABC)

of ~,, q - 1 times generates a continuous curve T

passing through all the elements of the unstable

cycle. Thus the curve

v'= Tk(V)

is identical with T except for the segment ABC.

Due to the contraction along the stable manifold

of C, homoclinic point B is mapped to homoclinic

point B'. Since the mapping is area preserving T'

must then intersect T in 2m + 1 points (for the

standard map at the Golden mean: m = 0). The

escaped area, S, is the dashed area in fig. 4 between T and T'. The numerical results- concerning

* The unstable (stable) manifolds at two neighboring points

of the unstable cycle are determined by solving for the eigenvalues of the tangent map and applying the mapping on points

along the relevant eigenvectors forward with Tk (or backward

with rk- 1).

87

D. Bensimon and L.P. Kadanoff/ Extended chaos and disappearance of KA M trajectories

the dependence of S on k - validate the theoretical

predictions:

(a) k < k c - W e observed the escaped area to

scale as:

S - q - d ° L * (ql k -- k c r )

0

.

0

taking d o = 3.049960 . . . . we could estimate ~/=

6.00 and ~,---0.99. T h e observed value of v is in

agreement with the R.G. value: v = 0.987463 . . . .

T h e scaling function L * ( x ) is shown in fig. 5.

(b) k = k c - We observed a p o w e r law decay of

the leakage rate, S, as Q increases (fig. 6)

s - q-do.

Jlltiilll/

0

0.08

0.02

i

'

]

'

I

0.06

'

'

0.08

' ~

I

0.06

x o +Y0 = do = 3.050 ___

0.02

0 i~

X1()46

5

.

L'

.

.

1

.

.

'~\

4

.

--.,,,\

3

~

2 --

0

"%~

,

.

,

I

0.2

I ~ 1 ~ I

0.1

0.2

0.3

I

,

I ~ I0.4

0.5

k

0.12

~

.9o

+

.92

o

.94

-

x

955

-

•

.965

-

.96

*

~-#xo.

,

.

I

Symbol

"*~x.~

"~-

0

0.04

0.04

T h e observed p o w e r is:

0.002.

•_Av

~

0.03

°° l

_ q-do exp [ - yql k - kcl" ] ,

-

6

-

0.10

-

0.08

-

'

I

'

I

'

I

0.06

0.04

,

0.4

x-qlk-kcl

0.6

0.02

0

0

~

Fig. 5. The scaling function for k< kc: L*(x). Notice the

two branches which are generated by n even (odd) Fibonacci

cycles (q, = F,,).

0.1

0.2

0.3

Fig. 7. The escaped area (dashed region), S for a curve passing through unstable cycle elements only at k= 1.5 (> kc).

a) p / q = 3/5, S = 1.6352 × 10-3; b) p / q = 5/8, S = 1.6374

X 10-3; C) p / q = 8/13, S = 1.6356 × 10 -3.

- 4

-10

I

0.4

I

I

0.8

I

]

~

1.2

I

1.6

M

I

2.0

I

I

2.4

loglo(q)

Fig. 6. The escaped area, S versus q ( = F,) at k : kc.

(c) k > k c - T h e results in that regime are particularly interesting since we expect the escaped area

to converge to a constant non-zero value at large

q. There exists, however, several numerical difficulties in converging to the correct unstable cycle for

supercritical values of k. T o o v e r c o m e these difficulties we used an algorithm which consisted in

predicting the initial point [ro(k), # 0 ( k ) ] - on the

relevant s y m m e t r y l i n e - b a s e d on the values of

( r o, 8o) for previous smaller values of k. An itera-

88

D. Bensimon and L.P. Kadanoff/ Extended chaos and disappearance of K A M trajectories

tive Newton method was then used to improve the

determination of the initial point to an accuracy

< 10-lo. To check for the correctness of the convergence, we verified that the order of the unstable

cycle elements was the same as for the k = 0 case.

A typical example of the form the escaped area

exhibits as higher cycles are used is shown in fig. 7

(at k = 1.5). Note the convergence of the leakage

rate to four significant digits. In these numerical

studies we could not study the behavior of the

escaped area for arbitrarily large cycles, since the

eigenvalue of the tangent map for large cycles is

extremely high (for example: k = 2.28 X 105 for

= 55/89 at k = 1.1). Such a high eigenvalue

means that after three iterations, with double precision arithmetic, one has lost all information about

the initial point.

The scaling function L~ (x) is shown in fig. 8.

Its asymptotic behavior is given by eq. (3.11) with

a critical exponent

Acknowledgements

d o -- 3.026 + 0.036.

The dashed area in fig. 9a is the escaped area in

the vicinity of 0. Now shift a segment of 3' a

distance e below 3', and consider the image 3" of

p/q

Note however the different form of the scaling

function

and

for n-even (odd)

Fibonacci cycles (q, = F,). We do not understand

that result in the framework of the renormalization

group for 2-D area-preserving maps [5, 6, 7].

(L*(x)

I

I

0-

'

'

Symbol

L*(x))

'

I

k

x

t..I..i

--4

,

#

'

'

I .99

i.O0

I

11.05

--

Appendix A

We will prove that a curve passing through

stable or unstable cycle dements extremizes the

escaped area.

Consider fig. 9a: In the vicinity of the q-cycle

point 0 one can use the tangent map to relate the

curve 3' to its image 3" (after q iterations),

(0/

IY

fr'

/ ~

I ' /

/

+o 1.98

.985

-2

'

We would like to acknowledge helpful discussions and correspondence on this work with R.S.

MacKay, I. Percival and J.D. Meiss.

This work is supported in parts by Grants NSF

D M R M R L 79-24007 and NSF 80-20609.

Y'

Y

(b/

..

/

/ I I

YES//

#

ISi

F

I,

-6

-8

-~

-2

log

I

0

~

,

,

.. r,

d-IIIIIIIA

~

X

C(I,-,)

I

2

[x--q(k-k )v]

Fig. 8. The scaling function for k > k c : L * ( x ) . Notice the

two branches which are generated by n even (odd) Fibonacci

cycles ( q. = Fn).

Fig. 9. a) The escaped area for a curve y passing through cycle

element O; b) the escaped area for the same curve "r moved

away slightly (by e) in the neighborhood of cycle element 0.

D. Bensimon and LP. Kadanoff/ Extended chaos and disappearance of KAM trajectories

that new line, which by now does not pass through

0 (see fig. 9b). The escaped area, S', is the dashed

one in fig. 9b. Clearly,

S ' = S -- SOAC,D, + SABCD.

XA-- M22

, -

Inserting (A.4) and (A.5) into (A.2):

/iS = S ' - S = (Mll + M22 - 2) e2"

21M2al

y = (M21x -- e)//M11,

with the lines y = 0 and y = - e :

/M2x,

(1-mxx)

XB=

M21 e,

- M22 and

(A.2)

Points A and B are determined by finding the

intersection of the line C'F' (the image of CF):

x^ =

89

(A.3)

(A.6)

(We have introduced the absolute value of M21,

since in fig. 9 M21 is implicitly assumed to be

positive.) Therefore, unstable cycles ( T r M > 2)

minimize the escaped area, and stable cycles

(ITr M I< 2) maximize it.

References

Then

SABCD=e( 1

XA+XB)2

=el1 _ ( 2 - M l l

(A.4)

-To evaluate SOAC,o, we use the fact that the mapping is area conserving and thus

So^c'D' = So^'co.

A' is the pre-image of A, thus: YA= 0 = M21" X^,

[1] R.S. MacKay, J.D. Meiss and I.C. Percival, Physica 13D

(1984) 55 (previous paper).

[2] E. Wigner, J. Chem. Phys. 5 (1937) 720 and LC. Keck, Adv.

Chem. Phys. 13 (1967) 85 consider analogous minimizations

of flow rates in phase space.

[3] J.M. Greene, J. Math. Phys. 20 (1979) 1183.

[4] J.N. Mather, preprint, Princeton (1982).

[5] S.J. Shenker and L.P. Kadanoff, J. Stat. Phys. 27 (1982)

631.

[6] L.P. Kadanoff, Phys. Rev. Lett. 47 (1981) 1641.

[7] R.S. MacKay, Proc. Conf. "Order in Chaos", Los Alamos

(1982), published in Physica 7D (1983) 283. See also thesis

(Princeton). The relation between the critical exponents

(v, do) used here and those found by MacKay (& a,B) are:

v = (logwS)-l; do=logw(afl) with W=(vr5 + 1)/2.

© Copyright 2026