16 H H I A T A L H E... A N D R E F L U...

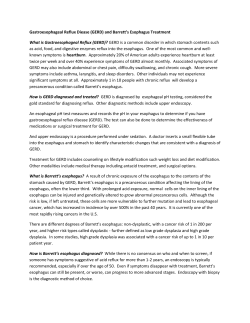

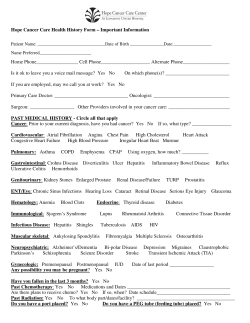

16 H I A T A L A N D H E R N I A R E F L U X E S O P H A G I T I S EDWARD PASSARO, JR. H iatal hernia and esophagitis are important conditions in both infants and adults. The pharmaceutical industry has directed much effort to treat these diseases because they are common. This chapter presents the forms of hiatal hernia and esophagitis and their sequelae. CASE 1 PARAESOPHAGEAL HERNIA A 72-year-old male was seen because of substernal pain and pressure within an hour after eating. He also reported recent gas and bloating, but no nausea or vomiting. There had been no weight loss, and his vigor and exercise tolerance were not diminished. An ECG and creatinine phosphokinase enzymes were normal both in the basal state and postprandial. Because of a mild anemia and guaiac positive stools a total colonoscopy was done and was normal. A UGI showed a portion of the stomach present in the left chest; however, the gastroesophageal junction was noted to be below the diaphragm. Esophagoscopy revealed an inflamed lower esophagus. With some difficulty the scope was inserted into a shortened gastric lumen and then, guided by the findings on the UGI, the scope was turned back to look at the fundic portion herniated into the chest. The edge of a gastric ulcer was seen and biopsied at about the level of the diaphragm. When the scope entered into the herniated portion of the stomach, a moderate amount of “coffee ground” secretions were aspirated. Subsequently, the biopsies of the gastric ulcer were reported as benign. At operation, a portion of the posterior wall of the fundus was found herniated through a 5-cm defect in the diaphragm to the left posterior lateral aspect of the cardioesophageal junction. On reducing the herniated stomach, a 1.5-cm ulcer was found where the stomach lay over the edge of the diaphragm. The ulcer was excised, the defect in the diaphragm repaired, and the stomach anchored to the anterior abdominal wall where a gastrostomy was fashioned. Following recovery from his operation he had no distress on eating and his Hct returned to normal levels. CASE 2 REFLUX ESOPHAGITIS AND BARRETT’S ESOPHAGUS A 48-year-old female noted the gradual onset of substernal pain shortly after starting a meal. Coincidentally she noticed heartburn, primarily at night, after retiring to bed. Although she had gained some 20 lb following the onset of menopause 3 years earlier, she had begun to lose weight in the past 2 months. Her Hct was normal and her stools were guaiac negative. Ultrasonography of the gallbladder did not reveal any stones. Chest and abdominal films were normal. After a 4-week course of elevating the head of the bed administering H2 receptor antagonists and liquid antacid therapy she had minimal relief of symptoms. There was no fur121 1 2 2 U P P E R G A S T R O I N T E S T I N A L ther weight loss. Esophagoscopy showed marked inflammation of the lower 6 cm of the esophagus. Biopsies of the inflamed region disclosed the presence of Barrett’s epithelium and operation was advised. Preoperative esophageal manometry and pH monitoring showed the LES pressure to be approximately 5 mmHg and the pH to be 3. A Nissen fundoplication was done. At follow-up 6 months later the pressure was 12 mm Hg and pH 7. The patient was asymptomatic and the esophagus appeared to be grossly normal. Repeat biopsies, however, showed the presence of Barrett’s epithelium and repeat EGD was recommended initially at 6-month intervals. T T R A C T tric contents into the lower esophagus may occur. In general, such LES relaxation is common and even beneficial, as for example, following eating. A few mints after a large meal can promote the eructation of swallowed air. This relieves the full or bloated sensation after a particularly large feast. Similarly, while reflux of food or acidic gastric contents into the lower esophagus occurs naturally several times during the course of a day, the pH is normally restored to neutral promptly by the swallowing of saliva and the peristaltic activity of the esophagus. Hiatal hernias may present with symptoms of esophageal reflux and, conversely, esophageal reflux disease often is associated with hiatal hernia. Hiatal hernias mostly are asymptomatic. There are two types of hiatal hernia. The most common by far (90%) is a sliding hiatal hernia where, as the name implies, a portion of the proximal stomach has herniated or slid into the chest (Fig. 16.1A). As a consequence, the cardioesophageal junction is displaced into the chest as well. Sliding hiatal hernias are most often discovered incidentally during investigations for other causes. They are thought to occur with increasing age and obesity. The rarer form of hiatal hernia is a paraesophageal hernia (Fig. 16.1B). Here the cardioesophageal junction may be below the diaphragm in its normal position and, GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS he lower esophagus has a physiologic sphincter mechanism to maintain a relatively high (15–20 mmHg) resting pressure. The sphincter is important in maintaining a barrier to gastric contents, so that food and/or acid secretions from the stomach do not reflux back into the esophagus. A number of agents including alcohol, tobacco, chocolate, and mints may cause the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) to relax and the pressure to fall, so that reflux of gas- A B FIGURE 16.1 (A) Sliding hernia. (B) Paraesophageal hernia. H I A T A L H E R N I A beyond it (para is Greek for “beyond”), a portion of the stomach is herniated through a diaphragmatic defect. The patient described in Case 1 has a typical paraesophageal hernia. These hernias may be present for long periods and can involve from only a small portion up to the entire stomach (the so-called upside-down stomach, as it is inverted about the horizontal axis when it comes to lie entirely in the chest), and can produce surprisingly little or no symptoms until a complication occurs. The usual complication is incarceration of the herniated stomach, producing symptoms of obstruction such as substernal pain and bloating (Case 1). In turn, the incarceration of the herniated stomach produces distention, ischemia, and ulceration. The patient presented in Case 1 experienced these changes, culminating in the formation of a gastric ulcer, which was bleeding and responsible for his anemia. This complication may be severe, as when the ulcer perforates into the hernia sac found within the chest or when it erodes through the gastric wall into the diaphragm. In these instances the herniated stomach may be very difficult to reduce into the abdominal cavity. A symptomatic paraesophageal hernia is a surgical emergency. Reflux esophagitis can occur without the presence of a hiatal hernia (Case 2). The reason for the apparent loss of the normal LES resting pressure and the reflux of gastric contents is not known; recognized provocative, if not causative, factors are alcohol, tobacco, and obesity, as noted above. Chronic irritation of the esophageal mucosa by reflux of acid and pepsin (or even alkaline secretions) from the stomach can lead to the development of metaplasia of the epithelium. Whereas the normal esophagus is lined by a flattened, squamous epithelium, metaplastic changes produce a columnar glandular epithelia that resembles the lining of the stomach. In fact, following the initial description of these changes it was thought that there was a proliferation and progression of gastric endothelium up into denuded regions of the inflamed lower esophagus. Subsequent studies have shown instead that Barrett’s epithelium represents a transformation of squamous epithelium into columnar epithelium. The involvement of metaplastic changes may range from minimal areas to the entire esophagus. Similarly, the histologic changes seen in biopsies may range from regular, well-organized cellular elements to marked dysplasia. Ultimately these changes can lead to the formation of malignancy (adenocarcinoma.) Barrett’s esophagus or epithelium is therefore an important prognostic factor for subsequent malignant degeneration. That is why the patient in Case 2 was followed by repeat endoscopic examinations. K E Y P O I N T S • Lower esophagus has a physiologic sphincter mechanism to maintain high resting pressure (15–20 mmHg) A N D R E F L U X E S O P H A G I T I S 1 2 3 • Although reflux of food and acidic gastric contents into lower esophagus occurs several times a day, pH is neutralized by swallowing saliva and peristaltic activity of esophagus • Most common hiatal hernia (90%) is sliding hiatal hernia, which occurs when a portion of proximal stomach herniates, or slides, into chest, causing cardioesophageal junction to be displaced into chest as well • Rarer hiatal hernia is paraesophageal (Fig. 16.1B); cardioesophageal junction may be below diaphragm in its normal position and, beyond it, a portion of stomach is herniated through diaphragmatic defect; a symptomatic paraesophageal hernia is a surgical emergency • Reflux esophagitis can occur without hiatal hernia • Chronic irritation of esophageal mucosa by reflux of acid and pepsin (or even alkaline bile) from the stomach can cause metaplasia of epithelium to develop • Barrett’s epithelium represents transformation of squamous epithelium into columnar epithelium; is an important prognostic factor for subsequent malignant degeneration R DIAGNOSIS eflux esophagitis is usually suggested by the history of substernal pain on eating associated with episodes of heartburn and the reflux of gastric contents (“water brash”) or food. In particular, the relationship of reflux to positional changes such as lying down at night or bending over to tie one’s shoes is very characteristic. Recent weight gain may exacerbate the symptoms. Symptoms associated with Barrett’s epithelium are particularly difficult to treat medically and therefore suggest a severe chronic form of the disease. By contrast, the reflux esophagitis that accompanies a sliding hiatal hernia is milder in form and responds more favorably to simple medical measures for treatment. The diagnosis is best established by esophagogastroscopy. All patients suspected of having reflux esophagitis should undergo esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). EGD not only establishes the diagnosis based on the findings of a reddened, inflamed, distal esophageal mucosa but also is important in ascertaining the stage of the disease, both by biopsy and by noting the presence or absence of strictures or overt malignancy. Barrett’s epithelium itself, however, is seldom recognized on inspection but should be suspected when the inflammatory process in the esophagus is severe, particularly after trials of medical therapy. Thus, biopsy should always be taken of the involved portions of the esophagus, as the incidence of malignancy is some 20-fold greater in patients with Barrett’s esophagus than those without. Esophageal manometry and pH measurements over a 24-hour period have been described and advocated by investigators of this disease. However, such a level of investigation is neither accepted nor tolerated by most patients 1 2 4 U P P E R G A S T R O I N T E S T I N A L and serves to confirm but hardly ever suggests the diagnosis. In a typical patient suffering from reflux, there is usually a lower resting LES pressure (Case 2) and when it is below 10 mmHg, Barrett’s changes are more common. Additionally, the pH is below 5 for long periods throughout both the day and night, both with the patient erect and recumbent. The presence or absence, as well as the differentiation of a sliding hernia from a paraesophageal hernia is best done by an upper gastrointestinal barium contrast study (UGI) series. Although endoscopy may suggest the presence of either a sliding or a paraesophageal hernia, it commonly misses the sliding hernia and it may be difficult to detect a paraesophageal hernia. The UGI series is helpful to the endoscopist in attempting to visualize and inspect the herniated portion of the stomach (Case 1). Rare congenital forms of diaphragmatic hernia can occur behind the sternum (Morgagni) or in the dorsal lateral aspects of the diaphragm (Bochdalek’s hernia). They are best diagnosed by UGI series. K E Y P O I N T S • Symptoms associated with Barrett’s epithelium difficult to treat medically, and suggest a severe form of this disease T R A C T Other diagnoses to be considered are biliary tract disease and peptic ulcer disease. The location of the pain and its temporal relationship to eating may be mimicked by biliary tract disease. In particular, stones in the common bile duct may produce epigastric pain rather than the more typical right upper quadrant pain produced by most gallbladder stones. Ultrasonography is helpful (Case 2). Endoscopy, which is done to confirm the diagnosis of reflux esophagitis as well as to grade the severity of the disease, also serves to detect unsuspected peptic ulcer disease. Occasionally, gastric ulcers localized on the lesser curvature of the stomach but unrelated to either hiatal hernias or esophageal reflux may present with symptoms identical to those in patients with reflux disease. Such ulcers are easy to detect on endoscopy and biopsy. In Case 1, endoscopy was of particular value in uncovering an ulcer in the patient’s herniated stomach that was responsible for bleeding and anemia. K E Y P O I N T S • Ruling out myocardial disease most important consideration in establishing diagnosis of reflux esophagitis • Also to be considered are biliary tract disease and peptic ulcer disease • Endoscopy is done to confirm diagnosis of reflux esophagitis • Diagnosis best established by esophagogastroscopy • Biopsy always taken of involved portions of esophagus, as malignancy is 20 times greater in patients with Barrett’s esophagus than those without • Presence or absence, and differentiation of sliding hernia from paraesophageal hernia best done by UGI series P DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS atients with angina or evolving myocardial infarction can have symptoms identical to those in patients with reflux esophagitis. Thus, ruling out significant myocardial disease is the most important consideration when establishing the diagnosis of reflux esophagitis (Case 1). A carefully taken history of pain related to exercise and unrelated to eating, decreased vigor and exercise tolerance, arrythmias and episodes of dyspnea, suggest cardiac disease rather than primary esophageal disease. Serial ECGs and creatinine phosphokinase serum and enzymes may help differentiate the two conditions. The response to sublingual nitroglycerin tablets is equivocal in both cardiac patients as well as esophageal disease patients, as both may obtain transient but definite relief. Rarely, when the diagnosis cannot be clearly established, perfusing the lower esophagus with a dilute solution of hydrochloric acid (Bernstein test) will reproduce the patient’s symptoms, whereas a saline solution as a control does not. T TREATMENT he treatment of reflux esophagitis is directed at correcting any identifiable defect and preventing further harmful changes in the esophageal mucosa. Sliding hiatal hernias and associated reflux esophagitis generally respond well to medical therapies. These include controlled weight loss, elevation of the head of the bed to reduce nocturnal reflux, and combinations of antacids and acid inhibitors such as histamine (H2) receptor blocking agents and omeprazole, a potent inhibitor of enzymatic processes responsible for acid production. Alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco use should be avoided. Repeat endoscopic evaluation of the esophagus should be done in 2–3 months to ensure that healing has taken place. Should esophagitis persist, antireflux procedures such as a Nissen fundoplication in which the lower 6 cm of the esophagus is wrapped with the gastric fundus (Fig. 16.2) should be offered. The procedure is highly effective (90%) in producing an increased LES resting pressure, and in markedly reducing if not eliminating reflux. When done by the laparoscopic technique the morbidity is very low. The treatment of symptomatic paraesophageal hernias is urgent, as the complications from unattended hernias can be catastrophic. These patients should be admitted promptly to the hospital, and nasogastric decompression of the stomach instituted to prevent further distention of H I A T A L H E R N I A A N D R E F L U X E S O P H A G I T I S 1 2 5 • None of procedures effective in preventing esophageal reflux reverse Barrett’s epithelium to normal O FOLLOW-UP utcome data on the careful follow-up of patients with Barrett’s epithelium following operation are not available. Follow-up endoscopic surveillance, initially at 6 months and subsequently at yearly intervals, is necessary to detect and treat malignant changes in the mucosa. This can be done by repeat esophagoscopy and biopsy or brush cytology of the distal esophageal mucosa. What is clear is that with each passing decade Barrett’s epithelium has a greater chance of being converted to an overt malignancy. SUGGESTED READINGS Spechler SJ: Comparison of medical and surgical therapy for complicated gastroesophageal reflux disease in veterans. N Engl J Med 326:786, 1992 FIGURE 16.2 Nissen fundoplication. the hernia, followed by operation. The herniated portion of the stomach, usually the posterior fundic wall, is reduced and then the defect sutured close (Case 1). The stomach is further anchored to the diaphragm and/or anterior abdominal wall to reduce recurrent herniation. Many surgeons will combine the reduction of the fundus with Nissen fundoplication. Patients who do not respond to medical therapy or those with Barrett’s epithelium present on biopsy should have an antireflux procedure to prevent continued damage to the esophageal mucosa. Although the Nissen fundoplication is the most widely utilized procedure, antireflux operations such as the Hill or Belsey repair achieve similar results, namely increased LES resting pressures. Although all the procedures are effective in preventing further esophageal reflux, none have been shown to cause reversal of Barrett’s epithelium to normal. Thus, patients with this lesion require continued surveillance. K E Y P O I N T S • Sliding hiatal hernias and associated reflux esophagitis respond well to medical therapy • Nissen fundoplication highly effective (90%) in producing an increased LES resting pressure, and in markedly reducing if not eliminating reflux This cautiously conducted multi-institutional study shows that carefully selected patients are best treated with surgery. Stein HJ: Complications of gastroesophageal reflux therapy. Role of the lower esophageal sphincter, esophageal acid, and acid alkaline exposure and duodenogastric reflux. Ann Surg 216:35, 1992 Comprehensive comparisons of known etiological factors in the incidence of complications. QUESTIONS 1. A paraesophageal hernia in contrast to a sliding hernia has? A. The cardioesophageal junction located below the diaphragm. B. A greater tendency to incarcerate the herniated stomach. C. Become a surgical emergency when the patient develops symptoms. D. All of the above. 2. Reflux esophagitis? A. Can occur without the presence of a hiatal hernia. B. Is associated with reduced LES pressure. C. Can cause Barrett’s epithelium. D. All of the above. (See p. 603 for answers.)

© Copyright 2026