Matthew Morris, Spring Cleaning for Mass DOR, Final Published

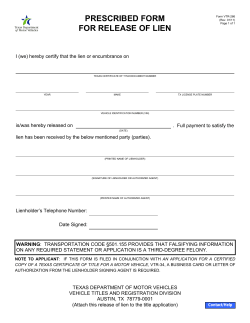

state tax notes™ Spring Cleaning for the Massachusetts Legislature and the DOR by Matthew A. Morris Matthew A. Morris is a partner at Kerstein, Coren & Lichtenstein LLP, Wellesley, Massachusetts. His practice areas include federal and state tax controversy resolution, representation in federal and state voluntary disclosure programs, state sales and use tax controversies, tax planning, and estate planning. He can be reached at mmorris @kcl-law.com. Matthew A. Morris In this article, Morris examines three problematic issues — lien subordination, discharge of indebtedness income relating to the sale of a principal residence, and the lack of guidance on passive foreign investment company income for individual taxpayers — that the Massachusetts legislature and Department of Revenue should review and possibly improve in 2015. Now that their long winter1 has ended, many Massachusetts residents will begin their spring cleaning. Windows latched tight since late November will be opened, and the fresh air that follows will provide new energy to resume long-neglected projects. What was accepted as commonplace during the stagnant winter months will now be subject to closer inspection to identify what should be repaired, discarded, or replaced. The same should be true this spring for the Massachusetts Department of Revenue and the Massachusetts legislature. After the conclusion of tax season on April 15, the legislature and the DOR should review tax laws and regulations to determine (1) whether each law or regulation is in proper working order, (2) what would be required to repair and perhaps improve laws and regulations that are not working properly, and (3) whether new laws and regulations are required. Massachusetts needs to clean house, especially regarding those tax laws and regulations that diverge from their federal counterparts without principled explanations for doing so. 1 See, e.g., Alan Taylor, ‘‘What Record-Breaking Snow Really Looks Like,’’ The Atlantic Photo, Feb. 17, 2015. State Tax Notes, April 6, 2015 This article describes three problematic items the legislature and the DOR should review carefully in its statutory and regulatory spring cleaning. The list is not intended to be comprehensive or exclusive. However, the three items should provide the legislature and the DOR with a productive starting point. The first two items (lien subordination and discharge of indebtedness regarding a sale of a principal residence) relate to unprincipled inconsistencies between Massachusetts and federal income tax laws; the third problematic item, passive foreign investment company income, regards an issue on which Massachusetts laws and regulations are silent. Problematic Item No. 1: Lien Subordination The Massachusetts lien subordination regulation (830 CMR 62C.50.1(7)) is problematic because it does not allow the DOR to subordinate its interest to the interest of a junior creditor even if that subordination will facilitate collection of the underlying tax liability. Subordination is typically defined as the process by which a priority creditor will subordinate its interest in the debtor’s property to allow the debtor to obtain new financing from a new lender who requires a superior position to make the loan. The Internal Revenue Manual defines subordination as ‘‘the process of allowing a junior creditor a position ahead of the Service lien regarding any part of property subject to the Federal tax lien.’’2 Whereas the Internal Revenue Code, on which the DOR lien subordination regulations are based, allows the IRS to subordinate its interest if the amount of the subordinated interest is paid to the IRS in full or if subordination will facilitate collection of the tax liability, the DOR regulations state that lien subordination is only available when the DOR has been paid an amount equal to the subordinated interest. Although payment of the subordinated interest to the DOR should be required in a mortgage or refinance transaction, the DOR should also be able to subordinate its interest without full payment to facilitate collection of the tax liability. The Massachusetts lien subordination regulation states: In appropriate circumstances, the Commissioner may certify that the tax lien as to some part of the property 2 IRM section 5.12.10.6(1): Subordination of Lien. 63 (C) Tax Analysts 2015. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. SPECIAL REPORT Special Report The Massachusetts regulation is based on IRC section 6325(d), which states that the secretary ‘‘may issue a certificate of subordination of any lien imposed by this chapter upon any part of the property subject to such lien if (1) there is paid over to the Secretary an amount equal to the amount of the lien or interest to which the certificate subordinates the lien of the United States.’’ Similarly, section 6325 regulations state that a lien may be subordinated on the grounds of full payment under section 6325(d)(1) ‘‘if a notice of Federal tax lien is filed and a delinquent taxpayer secures a mortgage loan . . . and pays over the proceeds of the loan to the appropriate official after an application for a certificate of subordination is approved.’’4 Under existing IRS regulations, however, full payment of the proceeds of the loan is not required when the proceeds of the loan are required to maximize the collection potential from the taxpayer.5 IRC section 6325(d) contains two additional grounds for granting a certificate of subordination that are not referenced in the Massachusetts regulation: (2) the Secretary believes that the amount realizable by the United States from the property to which the certificate relates, or from any other property subject to the lien, will ultimately be increased by reason of the issuance of such certificate and that the ultimate collection of the tax liability will be facilitated by such subordination, or (3) for any lien imposed by section 6324B [relating to estate taxes], if the Secretary determines that the United States will be adequately secured after such subordination. In contrast to IRS regulations, Massachusetts regulations only permit subordination when the amount of the subordinated interest is paid in full or when full payment is placed in an escrow account. Although the DOR’s regulatory requirement for full payment of the liability makes sense in the context of a mortgage or refinancing transaction for an individual taxpayer, it does not make sense in a revolving credit arrangement in which a lender extends financing to a business taxpayer on the basis of new accounts receivable. If the taxpayer is a business that relies on a revolving line of credit as a source of working capital to keep the business 3 830 CMR 62C.50.1(7). 26 CFR section 401.6325-1(d)(1). 5 26 CFR section 401.6325-(1)(d)(2). 4 64 operating, requiring full payment of the subordinated lien would jeopardize ongoing business operations as well as further collections. Massachusetts state courts do not appear to have addressed that issue directly,6 but the U.S. Tax Court in Alessio Azzari Inc. v. Commissioner7 stated that a lender of a revolving line of credit does not stand in a priority position regarding accounts receivable acquired more than 45 days after the IRS filed its notice of federal tax lien, because the lender’s interest in those receivables cannot be perfected until the services giving rise to those receivables have been rendered. Similarly, the accounts receivable in which the creditor holds a security interest might have priority over the DOR’s tax lien only to the extent that those accounts receivable existed before the DOR’s lien filing. Thus, the new accounts receivable generated after the DOR lien filing date could be construed as new collateral for new financing, in which case the DOR would have a priority position over the revolving creditor. The limited Massachusetts guidance regarding subordination of state tax liens focuses on mortgage or refinancing transactions rather than revolving lines of credit. For example, in ‘‘Betterments and Liens: Assessment and Collection Issues,’’ the Massachusetts DOR, Division of Local Services, presents a case study in which a valid lien was filed against a homeowner who ‘‘wants to refinance his mortgage and the potential lender has requested the town to subordinate its lien to the mortgage.’’8 Further, the DOR instructions titled ‘‘Request for Partial Release of Lien, Certificate of Subordination’’ require a ‘‘Closing Attorney’s statement listing the distribution of funds available from the sale of the property or the refinance of the mortgage.’’9 There is no discussion in the DOR guidance regarding the circumstances in which the DOR would be entitled to subordinate its lien other than those circumstances in which the DOR is paid in full the amount of the subordinated interest in a mortgage or refinancing transaction. Although Massachusetts reg. section 830 CMR 62C.50.1(7) does not mention facilitation of tax liability as grounds for lien subordination, it does allow for a consideration of that factor in the context of a lien release: ‘‘The Commissioner may issue a release of lien as to a part of the property subject to a tax lien, provided that the Commissioner is satisfied that such partial release will facilitate the collection of the outstanding tax liability.’’ A lien release is a 6 But see Tremont Tower Condo. LLC v. George B.H. Macomber Co., 436 Mass. 677, 678 (2002) (lenders for a construction project in downtown Boston refused to fund applications for loan advances until the holder of a mechanic’s lien ‘‘executed a partial waiver and subordination of lien each month’’). 7 136 T.C. 9 (2011). 8 Massachusetts DOR, ‘‘Betterments and Liens: Assessment and Collection Issues,’’ Workshop A, Case Study 9, at 12. 9 These instructions cannot be cited because they are taxpayerspecific and are unavailable in a generic format on the DOR website. State Tax Notes, April 6, 2015 (C) Tax Analysts 2015. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. subject to the tax lien is subordinate to a lien or interest held by another party, if there is paid to the Commissioner an amount equal to the amount of the lien or interest to which the tax lien is made subordinate. If the certificate of subordination is to be issued before such amount is paid over to the Commissioner, a separate escrow account must be established in full amount, to secure the tax lien.3 Special Report The DOR’s administrative guidance supports the ‘‘administrative oversight’’ theory by offering conflicting interpretations of the requirements for lien subordination. DOR Administrative Procedure 631 titled ‘‘The Collection Process’’ states that ‘‘a taxpayer may find that he or she can pay a tax in full or in part only if the Department either partially releases a lien or allows another lien holder to have priority over DOR’s lien.’’10 Further, DOR instructions titled ‘‘Request for Partial Release of Lien, Certificate of Subordination’’ state that the ‘‘Commissioner may issue a release of a lien as to a part of the property subject to a Tax Lien or a Certificate of Subordination provided that the Commissioner is satisfied that the issuance of such document will facilitate the collection of the outstanding tax liability.’’11 That suggests that high-level DOR officials, who have presumably reviewed and approved the instructions, do not construe the grounds of ‘‘facilitating collection of the tax liability’’ as unique and exclusive to partial releases. The IRM instructs its employees to exercise discretion when determining whether to subordinate a federal tax lien: The Service must exercise good judgment in weighing the risks and deciding whether to subordinate the federal tax lien. The Service’s judgment is similar to the decision that an ordinarily prudent business person would make in deciding whether to subordinate his/her rights in a debtor’s property in order to secure additional long run benefits.12 Just as the IRS is expected to exercise the judgment of an ‘‘ordinarily prudent business person . . . in deciding whether to subordinate his/her rights in the debtor’s property in order to secure additional long run benefits,’’ so should the DOR. For a revolving line of credit or any other type of financing arrangement, the DOR should be entitled to subordinate its interest if the long-run benefits of the lien subordination — which may keep the business alive, thereby generating the capital required to pay the underlying liability in full over the next several years — justify the subordination as a prudent business decision. On the basis of the unprincipled inconsistencies between federal law and DOR regulations discussed above, the DOR should consider supplementing the existing lien subordination regulation with additional provisions that would allow for subordination to assist collection of the tax liability. This is not a situation in which the entire regulation would need to be discarded and replaced in order to restore it to proper working order. The DOR simply needs to add new language to the existing regulation to clarify that the same standards that apply to lien releases (payment in full or facilitating collection of the tax liability) also apply to lien subordinations. Problematic Item No. 2: Cancellation of Debt Income Regarding the Sale of a Principal Residence As the lien subordination issue discussed in the first part illustrates, the DOR’s interpretation of Massachusetts tax laws can lead to unfairness and uncertainty when the DOR departs from federal guidance on the same tax issue without a principled reason for doing so. The same is true for discharge of indebtedness, or cancellation of debt income (CODI), incurred in connection with a principal residence. While the IRS allows taxpayers to exclude CODI from gross income, the DOR refuses to extend relief to those same taxpayers on the basis that the federal mortgage debt relief forgiveness provisions were enacted after January 1, 2005. The abuses and excesses of the subprime mortgage market in the late 2000s led to a sharp drop in home prices that left many homeowners under water (that is, the amount of the mortgage exceeded the fair market value of the property).13 When homeowners (or banks through foreclosures and short sales) sold those underwater properties, the former homeowners were left in an impossible tax and financial situation: Those individuals had not only lost their homes without adequate funds to pay the outstanding mortgage in full, but they were also responsible for reporting and paying income tax on CODI incurred in connection with the bank’s writeoff of the outstanding mortgage balance after the property was sold (usually in a foreclosure or short sale). In most cases, the foreclosed or short-sold taxpayers did not have the resources to pay the income tax liability incurred in connection with CODI. In response to this situation and the associated income tax consequences for foreclosed and short-sold taxpayers, Congress enacted the Mortgage Forgiveness Debt Relief Act (MFDRA) in December 2007.14 Specifically, the MFDRA allows taxpayers to exclude CODI from gross income when CODI is incurred in connection with the taxpayer’s principal residence.15 The 13 10 AP 631.1.2: Partial Release of Lien and Subordination of Lien. Supra note 9. 12 IRM section 5.17.2.8.6(4) (Dec. 14, 2007). 11 State Tax Notes, April 6, 2015 See John V. Duca, ‘‘Subprime Mortgage Crisis,’’ federalreserve history.org, Nov. 2013 (‘‘Prices fell so much that it became hard for troubled borrowers to sell their homes to fully pay off their mortgages — even if they had provided a sizable down payment’’). 14 See Bloomberg BNA Tax Practice Series para. 1040.04.F.1. 15 Id. 65 (C) Tax Analysts 2015. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. full waiver of the DOR’s interest in the underlying property, whereas a lien subordination is a retention of the DOR’s interest in the property as a lower-priority creditor; it therefore seems illogical and inconsistent for the DOR to make it easier for a taxpayer to achieve a more complete, taxpayerfavorable remedy (release), but to make it more difficult for a taxpayer to achieve a less complete, DOR-favorable remedy (subordination). That unprincipled inconsistency between lien releases and subordinations suggests that the difference between federal and Massachusetts law is nothing more than an administrative oversight. Special Report Massachusetts does not recognize the principal residence debt forgiveness provisions of the MFDRA because the MFDRA was enacted after January 1, 2005. DOR Technical Information Release (TIR) 13-2 states that ‘‘in general, the Massachusetts personal income tax follows the provisions of the Internal Revenue Code . . . as amended on January 1, 2005 and in effect for the taxable year, in determining Massachusetts gross income.’’19 That statement derives from the definitions of the terms ‘‘code’’ and ‘‘federal gross income’’ set forth in Massachusetts General Laws, Chapter 62, section 1: When used in this chapter the following words or terms shall, unless the context indicates otherwise, have the following meanings: (c) ‘‘Code,’’ the Internal Revenue Code of the United States, as amended on January 1, 2005, and in effect for the taxable year; but Code shall mean the Code as amended and in effect for the taxable year for sections 62(a)(1), 72, 105, 106, 139C, 223, 274(m), 274(n), 401 through 420, inclusive, 457, 529, 530, 3401 and 3405 but excluding sections 402A and 408(q). (d) ‘‘Federal gross income,’’ gross income as defined under the Code.20 Because there appears to be no principled reason for Massachusetts to tax CODI that the federal government excludes, the legislature should add section 108 to the list of sections for which the term ‘‘code’’ means ‘‘the Code as amended and in effect for the taxable year.’’21 By adding code section 108 to the list of sections in Mass. Gen. Laws Chapter 62, section 1(c), the legislature will extend a significant income tax benefit to its constituents who may otherwise be forced to recognize CODI on the sale or foreclosure of their underwater principal residences. That minor statutory addition will help restore the fairness and functionality of Massachusetts laws regarding mortgage-related CODI forgiveness. Problematic Item No. 3: Guidance on PFIC Income PFIC income is an exceedingly complicated concept at the federal level, and is even more confusing at the state level. Generally speaking, PFIC income is income derived from an investment in a foreign corporation if (1) 75 percent or more of that corporation’s income is passive income or (2) the average percentage of assets held by the corporation during the tax year which produce passive income or which are held for the production of passive income is at least 50 percent.22 The classic example of PFIC income is interest, dividends, and capital gains generated from a foreign mutual fund. It is the IRS’s position that each foreign mutual fund is to be treated as a separate PFIC for federal income tax purposes.23 For purposes of this article, we will focus on three different reporting regimes for PFIC income: the default rules under IRC section 1291, the qualified electing fund (QEF) election under IRC section 1295, and the mark-to-market election under IRC section 1296. IRC section 1291 establishes the default rules for taxation of PFIC income.24 The basic default rules, which do not require an affirmative election, comprise three distinct requirements: • Excess distributions will be allocated ratably to each day in the taxpayer’s holding period for the stock.25 Excess distributions are defined as the amount of the distributions received during the tax year over 125 percent of the average amount received in respect of 20 Mass. Gen. Laws c. 62, section 1 (emphasis supplied). Id. 22 IRC section 1297(a). 23 See IRS LTR 200752029 (‘‘an unincorporated, open-ended, limited purpose trust’’ established under the laws of a non-U.S. jurisdiction, which was created for investment purposes and qualified as a mutual fund trust under the laws of the jurisdiction in which it was organized would be regarded as a foreign corporation for U.S. income tax purposes). 24 See generally IRC section 1291. 25 IRC section 1291(a)(1)(A). 21 16 IRC section 108(a)(1)(e). H.R. 5771, which extended the CODI relief provisions of the MFDRA to tax year 2014, was signed into law by President Obama on December 19, 2014. 17 IRC section 163(h)(3)(B). 18 See IRS, ‘‘The Mortgage Forgiveness Debt Relief Act and Debt Cancellation’’ (last updated Jan. 2015). 19 Massachusetts DOR, TIR 13-2: Massachusetts Tax Year 2013 Exclusion Amounts for Employer-Provided Parking, Transit Pass and Commuter Highway Vehicle Benefits (Jan. 31, 2013). 66 State Tax Notes, April 6, 2015 (C) Tax Analysts 2015. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. MFDRA’s new exclusion from the discharge of indebtedness rules, IRC section 108(a)(1)(E), states that gross income does not include any amount that would otherwise be includable in gross income as discharge of indebtedness income if ‘‘the indebtedness discharged is qualified principal residence indebtedness which is discharged before January 1, 2015.’’16 Qualified principal residence indebtedness is defined as ‘‘acquisition indebtedness’’ incurred in connection with the principal residence of the taxpayer in an amount not to exceed $2 million. Acquisition indebtedness is defined in IRC section 163(h)(3)(B) as ‘‘debt incurred in acquiring, constructing, or substantially improving the home and is secured by the home.’’17 Thus, the proceeds of a first mortgage that enable the homeowner to purchase or build the home and the proceeds of a second mortgage that enable the homeowner to substantially improve the home both fall under the definition of acquisition indebtedness. However, the proceeds of a first or second mortgage used for any purpose other than ‘‘acquiring, constructing, or substantially improving’’ the taxpayer’s principal residence will not qualify for the exclusion. The CODI relief provisions of the MFDRA (as extended by later federal legislation) apply to discharges after January 1, 2007, and before January 1, 2015.18 Special Report 26 IRC section 1291(b)(2)(A). IRC section 1291(a)(2). 28 IRC section 1291(a)(1)(B). 29 IRC section 1291(a)(1)(C). 30 IRC section 1291(c)(1). 31 IRC section 1291(c)(2). 32 See generally IRC sections 1293 and 1295. 33 All PFIC income, including PFIC income taxed under the section 1291 default rules, must be separately reported on Form 8621, ‘‘Information Return by a Shareholder of a Passive Foreign Investment Company or Qualified Electing Fund.’’ 34 See IRC section 1293(a)(1). 35 See CFR section 1.1295-1(g)(1) (‘‘For each year of the PFIC ending in a taxable year of a shareholder to which the shareholder’s section 1295 election applies, the PFIC must provide the shareholder with a PFIC Annual Information Statement’’). 36 See generally IRC section 1294; CFR section 1.1294-1T. 27 State Tax Notes, April 6, 2015 marketable stock.37 The mark-to-market provisions of section 1296 require an affirmative election on Form 8621.38 Generally speaking, the mark-to-market rules enable PFIC shareholders to include in gross income the difference between the FMV and the adjusted basis in the PFIC at the end of the tax year. If the FMV of the PFIC at the end of the year is greater than the adjusted basis, the taxpayer will include the difference in gross income; if the FMV of the PFIC at the end of the year is lower than the adjusted basis, the taxpayer will be entitled to claim that amount as a loss to the extent of mark-to-market gains reported in prior tax years (referred to as unreversed inclusions).39 Chapter 62, section 2 of the Massachusetts General Laws states that ‘‘Massachusetts gross income shall mean the federal gross income, modified as required by section six F [relating to the computation of Massachusetts capital gains], with the following further modifications.’’ None of those modifications, or any other section of the Massachusetts General Laws, requires PFIC income to be added to or subtracted from federal gross income for Massachusetts income tax purposes. Although by law Massachusetts gross income is based on federal gross income, PFIC income presents two distinct problems for Massachusetts income tax purposes: (1) PFIC income is not one of the specified categories of income identified on the Massachusetts Form 1 and (2) PFIC income generated under the QEF and mark-to-market elections might be subject to Massachusetts income tax, whereas deferred PFIC gains under the default section 1291 rules might not. Unlike income tax forms for other jurisdictions,40 Massachusetts Form 1 does not use federal adjusted gross income as a starting point to which various state-specific additions and subtractions are made. Instead, Form 1 requires taxpayers to report some types of income (for example, wages, taxable pensions and annuities, business/ profession, or farm income/loss) and uses a catchall provision for other income in Schedule X. The Form 1 instructions state that Massachusetts gross income includes ‘‘any other income not specifically exempt,’’ and the Schedule X instructions state that ‘‘other Massachusetts 5.2 percent income reported on U.S. Form 1040, line 21 and not reported elsewhere in Form 1’’ should be reported on line 37 See generally IRC section 1296. Generally speaking, marketable stock is stock that is regularly traded on a national securities exchange registered with the SEC or any exchange or other market for which the IRS determines has adequate rules. See IRC section 1296(e)(1)(A). Marketable stock is also ‘‘stock in any foreign corporation which is comparable to a U.S. regulated investment company and which offers for sale or has outstanding any stock of which it is the issuer and which is redeemable at its net asset value’’ and any option on stock described in (A) or (B) above. IRC section 1296(e)(1)(B) and (C). 38 Supra note 33. 39 IRC section 1296(a)(2)(B). 40 See, e.g., Missouri 2014 Form MO-1040. 67 (C) Tax Analysts 2015. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. such stock during the three preceding tax years.26 When a PFIC is sold or otherwise disposed under the default rules, any gain recognized on the disposition will be treated as an excess distribution.27 • The taxpayer’s gross income for the year shall include only the amount of the excess distributions allocable to the current tax year and for pre-PFIC years.28 For most taxpayers, this simply means that the taxpayer’s gross income for the current tax year only includes the portion of the excess distribution attributable to that tax year. • The tax for the current tax year shall be increased by the deferred tax amount,29 which includes a deferred interest charge.30 The deferred tax amount is computed on the basis of the highest marginal rates applicable to the prior years in the taxpayer’s holding period.31 IRC sections 1293 and 1295 set forth the requirements for the QEF election.32 The QEF provisions of section 1293 require an affirmative election under section 1295, which must be reported on Form 8621.33 The QEF election enables a PFIC shareholder to report his ratable share of the PFIC’s ordinary income and net capital gains.34 The QEF election is generally the most tax-favorable PFIC tax option because it entitles shareholders to more favorable capital gains rates on their ratable share of the PFIC’s net capital gains. The shareholder’s ability to make a QEF election is limited by the PFIC’s underlying transparency — in order to make a QEF election, the PFIC must provide the shareholder with a PFIC annual information statement that contains enough information for the shareholder to determine her pro rata share of the PFIC’s ordinary income and net capital gains.35 Under IRC section 1294, PFIC shareholders who make a QEF election can also elect to defer payment of income tax on the shareholder’s pro rata share of the undistributed earnings of the PFIC until those earnings are actually distributed to the shareholder or on the occurrence of other specified events.36 IRC section 1296 sets forth the requirements for the mark-to-market election for PFIC income generated by Special Report The DOR and Massachusetts courts have been silent regarding the taxation of PFIC income.44 The lack of guidance regarding the taxation of PFIC income in Massachusetts has resulted in too much uncertainty for taxpayers. Without specific direction from the DOR, practitioners have started to reach their own conclusions regarding state taxability of PFIC income. Some taxpayers and practitioners might conclude that PFIC income (including PFIC income from QEF and mark-to-market elections) is not subject to Massachusetts income tax based on the fact that PFIC income does not fall within one of the specified categories of Massachusetts gross income.45 Other practitioners might report PFIC income as other income on Massa- 41 See 2014 Massachusetts Form 1: Resident Income Tax Return; 2014 Schedule X: Other Income; 2014 Form 1 Instructions at 17. 42 If a QEF election is made, the shareholder’s pro rata share of ordinary income will likely be reported as other income on Form 1040, line 21 (Schedule X, line 3 for Massachusetts income tax purposes), but her pro rata share of net capital gains will be reported separately on Schedule D of the Form 1040 (as well as Schedule D of the Massachusetts Form 1). 43 The same is true for taxpayers who have elected to use the alternative mark-to-market resolution under the IRS offshore voluntary disclosure program. Because the alternative mark-to-market resolution (authorized by the Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program Frequently Asked Questions A10) computes PFIC gains (and losses) under a flat 20 percent tax rate, the PFIC gains are not in federal gross income, even though the tax and deferred interest on those gains is added to the total tax for the year (‘‘Regular and Alternative Minimum Tax are both to be computed without the PFIC dispositions or MTM gains and losses’’). Therefore, OVDP participants may be able to avoid Massachusetts income tax on PFIC income on their federal change amended state returns by electing the alternative mark-to-market resolution. 44 Searches for ‘‘passive foreign investment company’’ or ‘‘PFIC,’’ both on the DOR website and on LexisNexis for Massachusetts state cases, produce zero results. 45 See, e.g., Philip S. Gross, ‘‘Tax Planning for Offshore Hedge Funds — The Potential Benefits of Investing in a PFIC,’’ 21 J. Tax’n of Inv. 2, Feb. 2004 (‘‘Many states base their taxable income on federal taxable income and the PFIC income allocated to prior years would not be includible in the federal taxable income base and hence may not be includible in state taxable income. Also, some states may tax only some types of income including dividend income but would not tax other types of income such as PFIC income which would generally flow through on the other income line, Line 21 of Form 1040’’). 68 chusetts Schedule X or on other sections of the Form 1. Because the catchall provision of Schedule X captures all income not specifically exempted, taxpayers and practitioners cannot be faulted for taking a cautious approach. Further, those taxpayers who have made a QEF election under section 1294 and an election to defer payment of tax on the undistributed pro rata share of the PFIC’s earnings under section 1293 might still be responsible for paying current-year Massachusetts income tax on those earnings because no deferral election is available at the state level. By allowing practitioners to reach their own conclusions regarding PFIC income, the DOR is indirectly supporting a system by which Massachusetts tax laws are applied differently to different taxpayers. The tax result in each case may depend on the strength of the practitioner’s advocacy rather than on economic reality. That potential for disparate interpretations and applications of Massachusetts tax laws regarding PFIC income requires guidance detailing exactly how (or whether) PFIC income should be reported for Massachusetts income tax purposes. Regarding income generated from QEF and mark-to-market elections, the DOR should follow the lead of other states46 by issuing administrative guidance clarifying that those categories of PFIC income should be reported as other income on Schedule X, line 3. Regarding income generated under the section 1291 default rules, the legislature has a decision to make: either pass a law specifically subjecting deferred gains from prior tax years to Massachusetts income tax, or do nothing and allow that category of income to escape Massachusetts income tax altogether. That is a situation in which the legislature and the DOR do not currently have the appropriate tools to address the needs of Massachusetts taxpayers, and therefore need to promulgate a new statute, regulation, administrative procedure, or technical information release that will clarify the taxation of PFIC income in Massachusetts. Conclusion The legislature, the DOR, and Massachusetts taxpayers would all benefit from a statutory and regulatory spring cleaning. The legislature and the DOR should consider three major problem areas, all of which arise from an actual (subordinations and mortgage debt relief ) or perceived (PFIC income) inconsistency between federal and Massachusetts income tax laws. For lien subordinations and mortgagerelated CODI relief, the inconsistencies between federal and Massachusetts law appear unintentional: In neither case does there appear to be a specific statutory or regulatory purpose for treating those categories of taxpayers differently for Massachusetts tax purposes than for federal tax purposes. 46 See, e.g., New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, ‘‘Passive Foreign Investment Companies (PFIC) Tax Liability’’ (Feb. 7, 2011) (‘‘Report any PFIC income gain or loss for the tax year as ‘Other Income’ on the appropriate income tax return’’). State Tax Notes, April 6, 2015 (C) Tax Analysts 2015. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. 3.41 The problem is that income generated by two of the three main PFIC categories — the QEF election and the mark-to-market election — is required to be reported for Massachusetts tax purposes,42 but income generated under the default (section 1291) rules is not. That is because the default rules under section 1291 only require taxpayers to report their ratable share of gain for the current tax year in current-year gross income; tax on the deferred gains from prior tax years is computed separately from the tax on current-year taxable income. This means that the deferred gain for prior tax years under section 1291 might escape Massachusetts income tax altogether.43 Special Report (C) Tax Analysts 2015. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. For the taxation of PFIC income, it is possible that the DOR’s silence on that issue speaks volumes. The DOR may share the perspective of many Massachusetts taxpayers and practitioners (1) that PFIC income generated under QEF or mark-to-market elections is required to be reported for Massachusetts purposes because those items of income are in federal AGI but (2) that deferred PFIC income generated under the section 1291 default rules is not required to be reported for Massachusetts purposes because it is not in current-year AGI for federal income tax purposes. If that is the DOR’s position on PFIC income, it should promulgate a regulation or issue administrative guidance to clarify the issue and promote consistency of tax treatment among similarly situated taxpayers who own foreign mutual funds or other PFIC investments. If the DOR determines that deferred PFIC gains generated under the section 1291 default rules should also be subject to Massachusetts income tax, the legislature should pass a new law that specifically includes that category of income in the scope of the definition of Massachusetts gross income set forth in Chapter 62, section 2(a). ✰ Come for tax news. Leave with tax wisdom. Tax Analysts offers more than just the latest tax news headlines. Our online dailies and weekly print publications include commentary and insight from many of the most-respected minds in the tax field, including Lee Sheppard and Martin Sullivan. To stay smart, visit taxanalysts.com. State Tax Notes, April 6, 2015 69

© Copyright 2026