Politicization, Political Appointments, and Corruption in Brazilian

Politicization, Political Appointments, and Corruption in Brazilian Federal Ministries Bruno Hoepers University of Pittsburgh [email protected] Paper prepared for Thirty Years of Democracy in Brazil: A Research Workshop Notre Dame – IN, April 20, 2015 This is a preliminary version. Please do not cite. 1 Abstract This paper evaluates whether and how political appointee positions are related with corruption in the Brazilian ministries. It develops a structural theory on political appointees (“cargos de Direção e Assessoramento Superior” – DAS) politicization which states that higher levels of party membership among political appointees and higher heterogeneity of DAS partisanship inside an agency affect the patterns of wrongdoings across ministries ceteris paribus. The simple number of DAS positions would not necessarily mean more bureaucratic corruption and possibly performance (Lewis 2008). Instead, levels of ministerial wrongdoings would be mainly explained by the level of politicization among appointees in conjunction with the size of the bureaucratic agency. Ministries with more personnel and larger budgetary resources are found to be more corrupt-prone as well. By using a novel panel dataset with information on DASs politicization in 26 ministries from 2010 to 2014 and other covariates, it was possible to partially confirm the main theoretical claims. Some limitations and possible avenues for future research are also discussed. 2 1. Introduction Presidents’ ability to manage and use personnel in the bureaucracy is crucial in presidential attempts to govern and control the governmental apparatus (Moe 1985 and 1994, Lewis 2011). Political appointees are very instrumental in presidential efforts to control the bureaucracy, to make the bureaucracy less insulated, and therefore more responsive, to the popular will, as well as to bring new ideas from outside the government agencies. Nevertheless, presidential appointments can also attract the interest of political actors interested in influencing policy-making in specific agencies or for patronage purposes (Horton and Lewis 2009, Lewis 2011). In Brazil, many believe that political appointee positions in Brazilian federal agencies (“cargos de Direção e Assessoramento Superior”, or DAS)1 are related with corruption scandals, wrongdoings, and patronage exchanges. More specifically, it is argued that individuals with political clout among members of the incumbent government but without professional credentials to perform certain function in government are nominated as political appointees, who in turn would act on the behalf of their political patrons and extract rents from their agencies for their own benefit as well as to their patrons’. Some DAS appointee positions, especially DAS levels 5 and 6 (from DAS 1 to 6), are responsible for making important decisions regarding the allocation of budgetary resources that could be used for rent-seeking purposes. Thus, agency performance would suffer as a product of excessive politicization in the appointment process2. Recent corruption scandals would lend credence to such 1 In this paper, DASs, appointees, or political appointees are used interchangeably. By politicization we understand “…substitution of political criteria for merit-based criteria in the selection, retention, promotion, rewards, and disciplining of members of the public service.” (Christensen 2004). The concept also applies to nominations that try to influence policy-making (Christensen, p. 2, 2 3 allegations. Agencies considered to have politicized appointees, i.e., appointees with partisan ties in their ranks (e.g., Ministry of Transportation, Cities, Agriculture, Labor, Tourism, and Sports) were involved in wrongdoings that resulted in the resignation of ministers at the start of president Dilma’s administration in 2011. Therefore, some believe that reducing the number of appointee positions – or reforming the appointment system in Brazil – is necessary to fight corruption and improve agency performance3. However, there is a paucity of studies showing whether, and how, political appointee positions are related to wrongdoings in the Brazilian agencies4 at the federal level and in other countries as well. In this study, my goal is to put some of the aforementioned claims about DAS appointments and corruption under more scrutiny. Are DAS appointee positions related to public misdeeds in Brazilian federal agencies? My argument is that we should look more carefully at the features of appointee positions and their distribution across federal agencies. That is, not only do agencies differ in their overall number of DAS positions in the aggregate, but they also present important structural differences across agencies that can explain whether and how public misuse of office for private gains take place. Agencies differ markedly in terms of DAS’s party membership patterns, DAS’s level of composition by civil service members, and the dispersion or concentration of “politicized DASs” (i.e., DAS with party membership) across agencies, and those differences help account for the patterns of corruption observed across the agencies. In order to Lopez et al 2013, p.2). In this study, the level of politicization in an agency is assessed by the proportion of appointees in each agency who have party membership and DAS fractionalization. 3 Aécio Neves propõe reduzir pela metade número de ministérios. Source: <http://eleicoes.uol.com.br/2014/noticias/2014/07/30/aecio-neves-propoe-reduzir-pela-metade-numero-deministerios.htm> 4 In this paper, agencies and ministries are used interchangeably. 4 empirically test those claims, I analyze an original panel dataset containing information about DAS positions on 26 ministries in addition to other variables (total number of employees in an agency, agency’s budget, agency employees’ per capita wages, literacy, and proportion of appointees that are career civil servants), from 2010 to 2014. As a measure for corruption, I employ a proxy measure based on the number of Special Taking of Accounts – STAs (i.e. “Tomada de Contas Especial” – TCE). Overall, it was found that the patterns of party membership among DAS in the agencies (which serves as a proxy for parties’ influence inside agencies) are positively related to the number of audit reports. Besides, the fractionalization of “politicized” DAS appointees presented a positive albeit non-statistically significant association with the number of audits. In other words, the higher the share of DAS with party membership, the higher is the number of Special Auditing Reports. However, the impact of other structural factors such as the agency’s budget and total number of employees are very important predictors of wrongdoings in the agencies. More specifically, agencies with higher budgets and more personnel present more problems of corruption than agencies with smaller budgets and fewer employees. The paper proceeds as follows. First, I put the theoretical discussion and contribution of this study in context by comparing it to what has been done in previous studies on appointee positions in Brazil and overseas (the US case). Next, I develop more clearly the theoretical argument, implications, and main hypotheses. Third, I present and explain the data used in this study and the variables. Forth, I proceed to the empirical analysis of the data and describe the models’ specifications and main results. Last, I 5 conclude with some general remarks about the main findings in the paper, empirical limitations, and possible avenues for future research on the subject. 2. Studying political appointee positions: the role of politicization Studies on political appointees have attracted the attention of scholars for decades. Attention has been paid to the study of White House personnel operations and the use of appointments. The literature has detected a growth in the number of such appointees, which has been more pronounced in agencies located at the Executive Office of the Presidency (Heclo 1975, Lewis 2008). Presidents have been found to politicize the appointment process. When doing so, ideology matters. Presidents target agencies whose ideologies are more similar to their own (Lewis 2008, 2011). Moreover, studies have also examined the change in the number of appointees across agencies. In the US, presidentes have been particularly focused on the goals of controlling the bureaucracy and satistying demands for patronage (Huber and Shipan 2000 and Lewis 2009, p.61), even though they are constrained in their efforts by concerns about administrative performance and the preferences of members of Congress. Scholars have also studied the background and qualifications of appointees (e.g., Krause and O’Connell 2013, Cohen 1998, Heclo 1975 and 1977, Mackenzie 1981). Few studies have investigated modern patronage practices in the US federal government, though (Horton and Lewis 2009, p.2, Gallo and Lewis 2012). Regarding the appointment of more than 1,000 individuals by the Obama administration, Horton and Lewis (2009) found that presidents tend to place patronage appointees in agencies with the same political ideology 6 as the president, that are less neutral to the president’s agenda, and where appointees are less able to compromise agency performance. Regarding the literature on the effects of workforce diversity on bureaucratic performance, scholarship is more limited in the public management literature and also in political science, which focuses more on social diversity impact (e.g., gender and race) on descriptive representation, with some important exceptions. For instance, Krause et al (2006) assess how “organizational balancing” between politically appointed agency executives and merit-selected subordinates lead to more accurate revenue forecasts in the U.S. states. Still, the partisan aspect (i.e., employees from different parties and their interactions inside agencies) is not explored. With respect to the Brazilian case, studies on appointments and personnel in the federal bureaucracy still have much to cover. Most studies are influenced by the public administration’s literature and concepts, are mainly descriptive or focus on specific agencies (e.g., Loureiro and Abrucio 1999, Santos 2009, de Almeida Corrêa 2011). Some studies have also analyzed the profile of medium and top-level bureaucrats in the Brazilian federal government with emphasis on their socio-demographic characteristics (D'Araujo 2007). Departing from previous studies and using newly available data, Praça et al (2011) found that the distribution of partisan and non-partisan appointees between and within ministries differ considerably and are not proportional to the number of seats parties have in Congress and the number of political appointment offices they control (2011, p.150). Another area of recent inquiry has been the analysis of turnover in federal agencies (Praça et al 2012, Lopez et al 2013). 7 Overall, the scholarship on appointees is varied, in development, and still very concerned with the trade-off between loyalty and competence. The role of patronage and the relationship between political appointees, politicization, and corruption are still underdeveloped. There are two important exceptions in the Brazilian case, though. For instance, Lopez et al (2013) assessed whether political factors such as minister’s party membership, minister’s party faction, and minister’s party ideology (among others) impact DASs’ turnover rates. Meneguin and Bugarin (2012) studied the role that two different incentive structures facing public employees (public civil servants or political appointees – DAS) exert at following or not corrupt conducts. Also using data on STAs, they found that ministries which have higher percentages of appointees as members of the public civil service (i.e., that joined the civil service via public examinations) presented fewer STAs after controlling for other factors such as year and agency’s budget. The current study also uses data on STAs and covers ministries, but uses a panel dataset with fewer time period (T). Differently from Meneguin and Bugarin, I consider more complex and direct differences among appointees on politicization across agencies by considering DASs’ party membership in each agency and its impact in agency corruption level. 3. The role of DAS’s politicization on agency corruption How does politicization among political appointees affect political corruption levels in bureaucratic agencies? The conventional wisdom in the literature and among followers of the Brazilian poilitics would suggest that ministries with more appointees 8 would be more corrupt and scandal prone than ministries with fewer appointee positions. As previously mentioned, I argue that the raw number of appointees per agency is not enough to understand the impact of politicization. First, agencies differ in terms of how many appointee positions are filled by career civil servants. Second, agencies with many appointee positions do not necessarily have more audits showing problems with corruption. [Figure 1 about here] For instance, as Figure 1 shows, the Ministry of Planning (MP) presents approximately 1000 appointees for the period 2010-2014, but accounts for only 2% of the STAs during the period. In contrast, the Ministry of Tourism (MTUR) presents the lowest number of appointees on average (total of 150 appointees in 2013), but ranks 4th in the proportion of STAs audited for the same period, as Figure 2 shows. On the other hand, several ministries with a higher proportion of DAS with party membership rank higher in number of STAs, such as MTUR and Labor (MTE). [Figure 2 about here] The figures aforementioned, although not conclusive, suggest the relationship between political appointments and corruption needs more theorizing. Drawing from insights in social identity theory and societal fractionalization (Cerqueti et al 2012 and Schikora 2014) and political economy regarding groups differences and their impacts on patterns of coordination and competition over resources (e.g., Fiorino & Petrarca 2012, 9 Roubini& Sachs 1989a and 1989b), I develop a structural theory which posits that the larger share of partisan appointees changes the relationship between regular civil servants and intergroup relationships between parties in an agency by increasing the degree of non-cooperative (or competitive) interactions between parties. As a result, a prisoner’s dilemma with respect to funding allocations ensues in which parties try to secure a larger share of agency resources to themselves and their constituents and interests in detriment of a more efficient allocation based on universalistic and efficiency parameters established by the career civil servants. The end result would be a net increase in budgetary spending being allocated inappropriately. The distribution of party membership among DASs is important in the broader context of coalition building in Brazil. The division of positions in the federal bureaucracy is a valuable commodity that the Executive can use in order to organize a broad governing coalition, along with the distribution of other resources such as individual amendments, public works contracts, and others. DAS positions allow parties to exert influence over the agencies’ operations, policy making, and resource allocations. Hierarchical institutions such as government agencies have as one of their main purposes to foster cooperative behavior among their employees in order to achieve their goals, which is important at different tasks such as spending decisions. However, many factors affect the capacity of employees to work cooperatively, such as power relations, career ambitions, and miscommunication, to name just a few. Heterogeneity of preferences inside an agency figures among those factors. Individual government coalition parties (represented in agencies by partisans possessing appointee positions) have different interests and constituencies to promote and appease. As a result, the struggle to promote 10 different party interests occurs inside the agencies. Partisan appointees (i.e., DAS with party membership) from each party constitute groups that engage in intergroup relations. Intragroup relations are usually assumed as more cooperative, while intergroup relations are considered to be more distrustful and resulting in more competitive interactions. Thus, as the proportion of partisan appointees inside an agency increase, the more resource allocation is seen as a zero-sum game, i.e. the higher the perception among employees of zero-sum goal relations. In other words, if one party does not secure funds to its interests then other parties, or the non-partisan career civil servants, will secure funds to promote their interests. Hence, relations among groups of partisans and of partisans among career civil servants become less cooperative and more competitive. The result of heightened competition for resources is a prisoner’s dilemma situation with respect to funding allocation. All employees inside an agency would prefer resource allocations to be more “rational” (less predatory) and more guided by universalistic and efficiency principles in the context of lower intergroup conflict (i.e., more internal cooperation inside an agency). In a more competitive setting and absent strong coordination in budget allocations inside an agency, the non-cooperative solution is for each party to try to divert resources for its interests and constituents in detriment of a more rational allocation. Thus, a larger proportion of DAS appointees with party membership inside an agency fosters non-cooperative behavior and distorts the allocation of government expenditures. Agencies also differ with respect to the degree to which one party is more “dominant” than others in an agency (i.e., whether a party has a higher number of DAS than other parties inside the agency). Higher levels of party fragmentation inside the 11 agencies (i.e., more DASs as members of different parties) lead to more internal competition for power inside the agencies. The higher the number of party interests struggling for space inside each agency, the higher will be the diversity of the political interests willing to use appointee positions for patronage and rent extraction. Heterogeneity in party membership inside an agency can be expected to aggravate resource misallocation in the bureaucracy. In agencies that are more heterogeneous in party membership composition among DASs, there will be more competition for resources because of the presence of more rivals (i.e., DASs members of different parties). In agencies with more heterogeneous party membership patterns, the transaction costs incurred in securing patronage goods and rent seeking goods (obviously scarce ones) can be higher because a) it is more difficult to successfully coordinate efforts to obtain the desired goods (i.e., need for more reliance on opposing interest in order to obtain goods that one side wants to appropriate for itself and deny to others), and b) there are more incentives for internal acts of sabotage and whistleblowing in heterogeneous agencies. Nonetheless, in agencies that are more homogeneous in party composition among DASs, there will be potentially less predatory competition for resources. The presence of rival partners is lower, and therefore the incentives to engage in possibly self-inflicted acts such as whistleblowing decrease. In addition, it is easier to coordinate and obtain cooperation for the acquisition and distribution of patronage goods and rent seeking goods than in agencies with more heterogeneous party membership outlook among DASs. In sum, the transaction costs involved in the acquisition of both types of goods will be lower in more homogeneous party membership composition among DASs. 12 Based on the aforementioned theoretical argument we can expect the following empirical implications from the theory. We can hypothesize that H1) corruption levels (or the number of STAs) will be higher in agencies with higher numbers of DASs party members (i.e., DASs that officially belong to a political party) than othersise. Likewise, H2) the more heterogeneous the party membership composition among DASs in an agency, the higher the corruption level (or higher number of STAs) in that agency, holding other factors constant. 4. Data and variables The Brazilian bureaucracy comprises more than 530,000 active employees. As of April 2013, 22,074 of these employees were political appointees, or DAS (an acronym of “Direção e Assessoramento Superior”, or “High Level Execution and Advisory”). They are responsible for the most important decisions inside federal agencies along with the ministers. They can be divided into two basic groups: DAS 1 to 3 and DAS 4 to 6. The first group comprises lower-level positions while the second occupy higher-level positions inside the Brazilian agencies’ organizational structures. Approximately 80% of DASs are of levels 1 to 3 and 20% of levels 4 to 6 (see Praça et al 2011 and 2012). Few scholars have collected data on DAS appointees and career civil servants in Brazil and carried out empirical analyses with it. Regarding the study of the relationship between bureaucracy and corruption in Brazilian federal agencies, the analysis of the share of career civil servants among appointees in each agency is an improvement (Meneguin & Bugarin 2012), but still not enough. A measure of partisan alignments 13 among appointees would be better. However, individual-level data on the subject is not currently available. Nonetheless, based on data made available by the Brazilian Electoral Supreme Court (TSE) in recent years, it became possible to cross the information on political appointees with party membership rolls and therefore to obtain an overall measure of party membership per agency. It is not a perfect measure of politicization, for many individuals in Brazil have party attachments without necessarily being officially members of a political party. That said, the measure on party membership among appointees is still valid for it is plausible to suppose that those in the federal government that are in party rolls are on average more devoted, interested in politics, and willing to be influenced by parties than other individuals. In a collective research effort with Sergio Praça and Andrea Freitas, we crossed the information from the Electoral Supreme Court on party membership rolls (name and party membership) for the entire country with information on each political appointee available at the federal government’s website “Portal da Transparencia”5. Based on that, I was able to compile the percentage of political appointees in each agency/year who are members of a political party. Furthermore, I also calculated a measure capable of assessing the dispersion or concentration of DAS party members inside the “population” of DAS in each agency. Based on Rae (1967), I calculated a DAS fractionalization index that uses the same formula as in the party fractionalization index: F = 1 - ∑vi2 . However, in this study “vi” is the share of DAS employees who belong to each political party i inside each agency. We can say that this index assesses the probability that two political appointees chosen at random would belong to different parties in a given agency. 5 Source: < http://www.portaltransparencia.gov.br >. 14 In addition to these variables, the dataset also includes the following covariates: the agency’s total number of employees (including non-DAS servants), the agency’s budget (in R$ millions), the agency’s wage per capita (i.e., the annual spending with personnel salary in the agency divided by the total number of agency employees), the agency’s literacy level (i.e., the percentage of public servants who have college-level education), the total number of DAS per agency, and the agency’s percentage of civil servants who are career civil servants. The data for total number of employees, agency’s wage per capita, and agency’s literacy level were obtained from the Ministry of Planning (Boletim Estatistico de Pessoal, or Personnel Statistical Report6). Data on the share of appointees who are part of the career civil service were obtained from the Ministry of Planning’s Secretaria de Gestão Pública (as in Meneguin and Bugarin 2012). Finally, the data on the number of STAs was obtained from CGU’s website7. The unit of analysis is ministry/year. There are data for 26 ministries and agencies with ministry status from 2010 to 2014. A list of the name of all ministries can be found in the Appendix. The summary statistics for the variables used in the multivariate analysis can be found on Table 1. [Table 1 about here]8 6 Source: < http://www.planejamento.gov.br/ministerio.asp?index=6&ler=t10204 >. 7 Source: < http://www.cgu.gov.br/ControleInterno/AvaliacaoGestaoAdministradores/TomadasContasEspecial/index.a sp >. 8 propntce = number of STAs, lactive = agency’s total number of employees, budget = agency’s budget, wagecapita = agency’s wage per capita, literacy = agency’s literacy level, ldastotal = total number of DAS per agency, dasfilratio = percent of agency’s DAS that belong to a political party, dasserv = DAS part of career civil service, fracdastotal = DAS fractionalization. 15 The dependent variable is the proportion of number of Special Taking of Accounts (i.e. Tomada de Contas Especial, TCE)9. The STAs are one of the tools used by the General Conptroller Office (CGU) in order to detect wrongdoings in the Brazilian bureaucracy. It is an administrative procedure that is carried out in agencies to recover misspent public funds from public officials or non-governmental organizations. CGU supervises the process and issues an Audit Report and Certificate giving its opinion on whether the investigation concerning the facts was appropriate or not and indicating which rules or regulations might have been disregarded10. The STAs are latter judged by the Court of Audit of the Union (Tribunal de Contas da União – TCU), which in the end attributes responsibilities and penalties to those deemed responsible for misdeeds in misallocation of budgetary spending allocations. Between 2001 and 2010, these special investigations of accounts identified loses to the state estimated in U$ 2.8 billion dollars (Vieira dos Reis 2012). A general overview of the distribution of STAs per ministry can be viewed at Figure 2. [Figure 2 about here] According to the graph, the number of STAs varies considerably across ministries. The Ministry of Health has had by far the highest number of STAs, followed by the Ministry of Education. There is considerable variation in the number of STAs across ministries. Some ministries such as the Ministry of Energy and Mining (MME) 9 I also considered the use of the number of firings of employees per ministry as an alternative dependent variable. However, the results obtained in the statistical analyses were dubious, of questionable reliability, and therefore were not included in the paper. 10 Source: < http://www.cgu.gov.br/english/default.asp >. 16 and Ministry of Development, Industry and Commerce (MDIC) present very few STAs. Most ministries have an average number of STAs between 10 and 50. Few ministries are responsible for most part of STAs, especially the Ministry of Health (MS) with more than 30% of STAs and the Ministry of Education (MEC). These numbers are not surprising. Both ministries are among the largest in personnel, budget, and national scope. However, some smaller ministries also present a high number of STAs, such as the Ministry of Tourism (MTUR) and Labor (MTE). A general preliminary overview of patterns among the independent variables can be visualized at Table 2. [Table 2 about here] The table shows a correlation matrix of the variables included in the multivariate analysis. The number of STAs correlate more significantly with “structural” factors such as the agency’s total number of appointees and the agency’s budget. Almost all the independent variables present significant correlations among each other. The matrix also suggests that agencies’ percentages of DAS party members is inversely correlated to total agency’s employee size, total agency’s DAS size, and also to DAS fractionalization or dominance - of lack thereof – of one party in an agency vis-a-vis other parties. In other words, political appointees who belong to political parties tend to be concentrated in agencies of small to middle size in personnel, of lower wages per capita, with larger budgets, and less where there is a larger proportion of career civil servants and a larger proportion of career civil servants with higher levels of formal education (i.e., college degree and higher). 17 5. Estimation procedures and results In order to empirically analyze the relationship between DASs’ politicization patterns and corruption in ministries, I proceed to a multivariate analysis of the panel dataset on STAs in the Brazilian ministries. There are different challenges to model estimation that must be addressed given the nature of the data at hand (short panel with a small number of observations, N = 130). Assumptions of normality are more difficult to meet. Moreover, there are important concerns with autocorrelation and hereroskedasticity in the residuals which, if present and unaccounted for, can severely bias the standard errors. First it is necessary to decide which type of panel estimation procedure is more appropriate: fixed effects, random effects, or simply ordinary least squares. I tested the null hypothesis that the coefficients estimated by the random effects estimator are the same as the ones estimated by the consistent fixed effects estimator. According to the Hausman test (Prob > chi2 = .55), it is not possible to reject the null, which means that the random effects model is more appropriate than the fixed efffect model. Additionally, I also tested whether a random effects estimator is more efficient and appropriate than an ordinary least squares estimator. By running a Breusch-Pagan Lagrangian multiplier (LM) test11, I verified whether the null hypothesis that variances across entities is zero (i.e., no significant difference across units, or ministries). The test rejects the null (Prob > chibar2 = .00), which means that there is evidence of significant differences accross ministries and therefore the random effects estimator is preferred over the OLS estimator. 11 xttest0 command in Stata. 18 Hence, the Breusch-Pagan test buttresses the study’s substantive claim that there are reasons to believe that differences across ministries have some influence on the proportion of STAs (e.g., agency size). Another concern is the presence of serial correlation. Usually not a significant problem in short panels (with larger Ns and small Ts), serial correlation causes the standard errors to be smaller than they actually are and also to have higher R-squares. I ran a Wooldridge test12 for autocorrelation in the data and tested for the null hypothesis of no first-order – AR (1) – autocorrelation. The null was rejected (Prob > F = 0.00), which suggests that the data has first-order autocorrelation. As a result, I estimated four multivariate panel models. Three models employ random effects estimators. The first model is a simple random effects model. The second model presents a random effects with Huber/White estimators (robust standard errors) due to concerns over eventual heteroskedasticity that might be present (if so, the standard errors would be biased). The third model is a random effects where the disturbances follow an AR (1) process (with autocorrelated disturbances). The fourth model fits a panel data linear model by using feasible generalized least squares (GLS), which allows estimation in the presence of first-order autocorrelation within panels and cross-sectional correlation and heteroskedasticity across panels. In this model each group is assumed to have errors that follow the same AR (1) process (i.e., the autocorrelation parameter is the same for all groups). In order to account for possibly skewed distributions that can be expected in a dataset with a small number of observations, I proceeded to the transformation of some 12 xtserial command in Stata. 19 variables in order to make the distribution of some variables closer to normal 13. I obtained the square root of DAS party membership and Total number of DAS, the cubic root of DAS fractionalization, and the log of the total number of employees. The following table presents the results. [Table 3 about here] In general, the four models display the same pattern of results. All models reject the null that the independent variables are jointly equal to zero. The first three models also explain the same amount of variance on STAs (R2 overall of approximately 5657%). Moreover, the coefficients in the three models present basically the same sign for each variable. The model accounting for AR (1) disturbances present slightly different coefficients than the other two models, but the overall results are mostly the same. The model shows a test for autocorrelation, based on the Durbin-Watson statistic. The value of the modified Durbin-Watson statistic or Baltagi-Wu LBI statistic (Baltagi and Wu 1999) indicates no autocorrelation. It presents a statistic of 1.92 (the values can be between 0 and 4). Thus, we can be moderately confident that autocorrelation is not biasing the results. The fourth model (GLS with AR (1) ) presents results are are mostly the same in comparison to the random effects models, except that DAS fractionalization and ministry literacy level present negative coefficients (in disagreement with theory for the former and in agreement with theory for the latter). The similarity of results across the 13 Selection of the appropriate transformation were based on numeric and graphical results obtained through the ladder and gladder commands in Stata. Based on the ladder command, I chose the transformations with the smallest chi-square statistics reported (the lower the Chi2, the more appropriate a transformation). 20 four models, notably for those which account for heteroskedasticity and first-order autocorrelation, gives us more confidence that the results are consistent and not affected by autocorrelation and hereroskedasticity in the disturbances. The variables that account for structural factors at the agency level (i.e., not directly related to political appointees’ politicization) strongly and positively predict more STAs, holding the other variables constant. Ministries with larger budgets tend to be more corrupt, which is in accord with our expectations. Ministries with larger budgets attract the attention of rent-seekers and tend to spend more money that can be diverted for specific constituencies in exchange for electoral support, kickbacks, or other advantages. The coefficient for total personnel size is positive and statistically significant. Such result conforms to this study’s theoretical expectations. In larger groups, incentives to free-ride are larger. It is more difficult to organize and coordinate collective actions in large groups (Olson 1965), which makes more difficult for authorities to sanction illegal behavior. In sum, larger agency size increases the potential for corruption by providing more resources that can be diverted and also by making more difficult to detect and sanction inappropriate or illegal actions. It is also worth noting the results for two other covariates, wage per capita and literacy level. Ministries with larger wages per capita present lower proportion of STAs, although the coefficients across models do not reach conventional levels of statistical significance. Such results are in line with expectations that higher wages decrease bureaucrats’ incentives to engage in corrupt acts. Furthermore, the coefficient for literacy level in the three random effects models were all positive and not statistically significant. Nevertheless, the GLS model present a significant and negative coefficient for that 21 variable, which is in conformity to the notion that agencies with more qualified personnel should be better managed, more concerned with efficiency (Lewis 2008, 2009, 2011), and possibly more capable of fostering cooperative behavior and detecting suspicious or inappropriate spending allocations. Tellingly, the coefficient for the total number of DAS in ministries is negatively and significantly related to the number of accounts in all models, which suggests that the total number of DAS per se is not necessarily related to more corruption and patronage as is usually assumed in the literature. Indications of this result are also displayed in Figure 1 and Table 2. The data suggest that in fact ministries with more DAS positions are more efficient and less corrupt-prone on average holding other factors constant. Such apparently counterintuitive result can at least in part explained by the fact that most DAS positions are available in ministries where concern for efficiency are more pronounced, such as in the Ministry of Finance (MF), Planning (MP), and the Attorney General of the Union (AGU). These type of ministries also allocate more DAS positions to career civil servants as a way of retaining and rewarding civil servants in those agencies, for DAS positions (especially DAS level 5 and 6) pay better salaries and give their occupants higher decision making power. Both main measures of DASs’ politicization (DAS party membership and fractionalization) are positively related to higher number of STAs (the former being statistically significantly while the latter is not across the first three models, and with a negative coefficient in the GLS model). That is, when the share of DAS with party membership is higher in a ministry, the number of STAs also tends to increase. The values for DAS fractionalization are also of some significance. It suggests that more 22 heterogeneous ministries in party membership composition among DASs may be prone to present more problems with wrongdoings than more homogeneous ministries. Overall, all four models depict a similar pattern. Ministries with more corruption tend to be those with more employees and more sizable budgets, but not those with more political appointees. It is higher in ministries with more DASs with party membership. In susbtantive terms, the difference in impact of DAS party membership and total number of DAS per ministry is also detected, as Figure 3 illustrates. [Figure 3 about here] The graphs in Figure 3 show the marginal effects of each variable on the proportion of STAs with a 95% confidence interval. According to the figures, as the proportion of DAS with party membership increase in a ministry, the probability of observing an increase in the proportion of STAs also increases sharply. As the proportion of partisan DASs double (e.g., from .2 to .4) the proportion in STA moves from 0 to .1. In sharp contrast, the figure on the right displays a sharp negative relationship between the proportion of STAs and the number of DAS per ministry. For instance, as the number of DAS moves from 0 to 20, the probability of observing an increase in the proportion of STAs decreases from .25 to approximately .1, everything else constant. Again, the politicization of DAS positions, rather than the sheer number of DAS positions across ministries, seem to be a key factor driving corruption in Brazilian ministries. 23 6. Conclusion It has been commonly assumed in Brazil that political appointee positions in the Brazilian bureaucracy are currently one of the main explanations for the corruption scandals that from time to time plague the federal government in Brazil. Either for patronage or rent-seeking purposes, federal appointees would be behind many attempts to embezzle funds to private interests and to curry favors by using the agencies’ resources. The politicization of the nomination of the appointee positions would be one of key reasons why DAS positions would be directly related to corruption. Nevertheless, there has not been a careful account of whether and how politicization would explain corruption levels in the Brazilian bureaucracy. Usually higher numbers of DASs have been equated to more wrongdoings. In this paper, I argue that the mere number of appointee positions per agencies belies more important distinctions that exist across DASs and agencies that are important at understanding whether and how DAS positions may be related to wrongdoings. I theorize that the politicization of DAS positions (as party membership among DASs inside the agencies and the degree of dispersion or concentration of DAS with party membership) would help explain differences in corruption patterns across agencies. Both factors would operate at increasing intergroup rivalry and lead to an increase in competitive rather than cooperative behavior among employees inside agencies. As a result of such heightened competition, the struggle for resources would assume a zero-sum aspect and a prisoner’s dilemma regarding the allocation of resources among parties would follow (Fiorino & Petrarca 2012, Roubini & Sachs 1989a and 1989b), thus affecting the divertion of funds in the ministries. 24 By using a dataset with information on the patterns of party membership and the fractionalization of such membership across 26 ministries from 2010 to 2014, in conjunction with other covariates, I was able to empirically provide some preliminary results. So far, the findings corroborated the theory that politicization at the appointee level, and not the sheer number of appointee positions per se, affects corruption levels as measured by the number of Special Taking of Accounts (STAs) as the proxy for corruption. However, agencies’ overall resource pool in terms of personnel and budget are also significantly related to corruption. That said, more needs to be done in order to buttress such results. For instance, there are concerns regarding the appropriateness of using STAs as a proxy for corruption. It is certainly a partial measure of corruption that can make some agencies to be more prone to investigations than others. Misallocation of funds is an important corrupt practice. However, other important practices not captured by the proxy such as regulatory activity, concession of rights to groups, and provision of non-monetary services can also result in corrupt exchanges between public and private actors. Maybe different accounting and investigation tools would show a different pattern of results. The models may not be thoroughly specified (i.e., with all the relevant independent variables), which can raise concerns about omitted variable bias. Furthermore, ministries are just a part of the Brazilian bureaucracy. Many important governmental activities are performed by other agencies with different structures than ministries, such as state-owned companies – some more impervious to public scrutiny and with ample resources that can be diverted for private gains, as the recent scandal14 involving the Brazilian oil company Petrobras 14 Source: < http://www.economist.com/news/americas/21637437-petrobras-scandal-explained-big-oily>. 25 shows – and more decentralized bureaus (autarquias). That said, it is always important to remember how difficult it is to measure corruption anywhere and what can be gained at using measures such as STAs for such purposes. The investigation of corruption patterns in other federal agencies and a movement towards individual-level analysis seem to be promising directions in this line of inquiry. We also need more and better qualitative accounts of the relationship between DAS employees, the importance of partisanship among DAS employees, and how they relate to other groups inside and outside the government. Much remains to be done and gained by better assessing the relationhsip between political appointees and their actions inside the bureaucracy. This paper is an attempt at providing a theory with applicability to other polities and contexts. 26 References Baltagi, B. H., & Wu, P. X. (1999). Unequally spaced panel data regressions with AR (1) disturbances. Econometric Theory, 15(6), 814-823. Cerqueti, R., Coppier, R., & Piga, G. (2012). Corruption, growth and ethnic fractionalization: a theoretical model. Journal of Economics, 106(2), 153-181. Christensen, J. (2004). Political responsiveness in a merit bureaucracy Politicization of the Civil Service in Comparative Perspective: the Quest for Control. New York: Routledge. Cohen, D. M. (1998). Amateur Government. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 8(4), 450-497. D'Araujo, M. C. (2007). Governo Lula: contornos sociais e políticos da elite do poder: FGV. de Almeida Corrêa, V. L. (2011). Perfil de los Ocupantes de Cargos de Confianza del Ejecutivo Federal Brasileño: una Comparación entre el Gobierno de FHC y de Lula (1996 a 2006). Revista ADM. MADE, 14(3), 28-46. Fiorino, N., Galli, E., & Petrarca, I. (2012). Corruption and growth: Evidence from the Italian regions. European Journal of Government and Economics, 1(2), 126-144. Gallo, N., & Lewis, D. E. (2012). The Consequences of Presidential Patronage for Federal Agency Performance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(2), 219-243. Heclo, H. (1975). OMB and the presidency: The problem of neutral competence. The Public Interest, 38(2), 80-98. Heclo, H. (1977). A government of strangers: Executive politics in Washington: Brookings Institution Press. Horton, G., & Lewis, D. (2009). Turkey Farms, Patronage, and Obama Administration Appointments. Vanderbilt Public Law Research Paper(09-24), 09-24. Huber, J. D., & Shipan, C. R. (2000). The costs of control: legislators, agencies, and transaction costs. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 25-52. Krause, G. A., Lewis, D. E., & Douglas, J. W. (2006). Political appointments, civil service systems, and bureaucratic competence: Organizational balancing and executive branch revenue forecasts in the American states. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 770-787. 27 Krause, G. A., & O’Connell, A. J. (2013). A measurement model of loyalty and competence for presidential appointees in the U.S. government agencies, 1977– 2005: a hierarchical generalized latent trait analysis. Lewis, D. E. (2008). The politics of presidential appointments: Political control and bureaucratic performance: Princeton University Press. Lewis, D. E. (2009). Revisiting the administrative presidency: Policy, patronage, and agency competence. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 39(1), 60-73. Lewis, D. E. (2011). Presidential Appointments and Personnel. Annual Review of Political Science, 14, 47-66. Lopez, F., Bugarin, M., & Bugarin, K. (2013). Partidos, facções e a ocupação dos cargos de confiança no executivo federal (1999-2011). CERME-CIEF-LAPCIPP-MESP Working Paper Series. Loureiro, M. R., & Abrucio, F. L. (1999). Política e burocracia no presidencialismo brasileiro: o papel do Ministério da Fazenda no primeiro governo Fernando Henrique Cardoso. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 14(41), 69-89. Mackenzie, G. C. (1981). The politics of presidential appointments: Free Press New York. Meneguin, F. B., & Bugarin, M. S. (2012). O Papel das Instituições nos Incentivos para a Gestão Pública. Textos para Discussao 118. Moe, T. M. (1985). The politicized presidency. In J. E. Chubb & P. E. Peterson (Eds.), The new direction in American politics (Vol. 235, pp. 269-271). Moe, T. M., & Wilson, S. A. (1994). Presidents and the Politics of Structure. Law and Contemporary Problems, 57(2), 1-44. Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Ma.). Praça, S., Freitas, A., & Hoepers, B. (2011). Political Appointments and Coalition Management in Brazil, 2007-2010. Journal Of Politics In Latin America, 141172. Praça, S., Freitas, A., & Hoepers, B. (2012). A rotatividade dos servidores de confiança no governo federal brasileiro, 2010-2011. Novos Estudos-CEBRAP(94), 91-107. 28 Roubini, N., & Sachs, J. D. (1989a). Political and economic determinants of budget deficits in the industrial democracies. European Economic Review, 33(5), 903933. Roubini, N., & Sachs, J. (1989b). Government spending and budget deficits in the industrial countries. Economic policy, 4(8), 99-132. Santos, L. A. d. (2009). Burocracia profissional ea livre nomeação para cargos de confiança no Brasil e nos EUA. Revista do Serviço Público, 60(1), 5-28. Schikora, J. T. (2014). How Do Groups Stabilize Corruption?. Journal of International Development, 26(7), 1071-1091. Vieira dos Reis, R. (2012). A Performance Measurement Framework for the Brazilian Office of the Comptroller General (CGU) Based on International Frameworks. The George Washington University. Washington DC. 29 Appendix MPS MEC MJ MF MS MMA MTE MAPA MDA MT MP MME MDIC AGU PR/CGU/ABIN MI MINC MD MCT MC MRE MCID MTUR MDS MPA ME Ministries included in the study Ministério da Previdência Social Ministério da Educação Ministério da Justiça Ministério da Fazenda Ministério da Saúde Ministério do Meio Ambiente Ministério do Trabalho e Emprego Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento Ministério do Desenvolvimento Agrário Ministério dos Transportes Ministério do Planejamento Ministério de Minas e Energia Ministério do Desenvolvimento, Indústria e Comércio Advocacia Geral da União Presidência da República Ministério da integração Nacional Ministério da Cultura Ministério da Defesa Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia Ministério das Comunicações Ministério das Relações Exteriores Ministério das Cidades Ministério do Turismo Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social e Combate 'a Fome Ministério da Pesca e Aquicultura Ministério do Esporte Note: Although AGU and PR are not ministries, both their office heads (Advogado-Geral da União and Ministro-Chefe da Casa-Civil) have ministerial status. 30 Figure 1. Average number of DAS and proportion of DAS with party membership per ministry (2010-2014) MF PR/CGU/ABIN MS MP MAPA AGU MJ MEC MCT MDS MTE MRE MD MINC MT MME MDA MC MPA MI MDIC MPS MMA ME MCID MTUR MDA ME MTE MCID MPA MAPA MS MTUR MI MPS PR/CGU/ABIN MINC MEC MDS MP MJ MMA MDIC MT MME MC MCT MF MD AGU MRE 0 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 # DAS 0 .1 .2 .3 % DAS with party membership Figure 2. Average proportion of STAs per ministry MS MEC MI MTUR MTE MCT MINC MDA MPS MDS ME MF MMA MC MP MD MAPA MCID MJ MT MDIC MPA PR/CGU/ABIN MME MRE AGU 0 .1 .2 .3 % STAs 31 Table 1. Summary statistics Mean Std. Dev. Proportion of STAs .149 .127 DAS party membership (%) .376 .071 DAS fractionalization (0-1) .577 .172 Total number of employees 8.717 1.592 Total number of DAS 21.778 8.445 Budget (R$ million) 6246.3 15531.95 Wage per capita (R$) 202612 131117.2 Literacy (%) .355 .162 DAS part of civil service (%) 3.214 14.577 Min 0 0 0.085 5.808 0 150.6 38512.4 .08 0.171 Max .623 .579 1 12.449 49.345 92702 584555.7 .691 86.49 32 Table 3. Determinants of the proportion of STAs in the Brazilian ministries Variables (1). RE (2). RE w/robust SE (3). RE with AR (1) (4). GLS with AR (1) DAS party membership (% squared) .373** (.124) .373*** (.096) .368** (.127) .357*** (.048) DAS fractionalization (0-1 cubic) .074 (.060) 0.074 (.043) 0.073 (.060) -.0170 (.021) Total number of employees (log) .036** (.011) .036*** (.009) .032** (.010) .036*** (.006) Total number of DAS (squared) -.004* (.002) -.004** (.001) -.004* (.001) -.006*** (.000) Budget (R$ million) 4.27e-06*** (1.01e-06) 4.27e-06*** (4.86e-07) 4.35e-06*** (9.26e-07) 5.70e-06*** (5.65e-07) Wage per capita (R$) -1.38e-07 (1.23e-07) -1.38e-07 (8.68e-08) -9.48e-08 (1.11e-07) -7.05e-08 (3.95e-08) Literacy (%) .051 (081) 0.051 (.066) 0.031 (.078) -.099*** (.023) DAS part of civil service (%) -.000 (.000) -.000*** (.000) -.000 (.000) -.000*** (.000) Constant -.261* (.120) -.261*** (.073) -.242* (.113) -.185** (.061) Wald chi2 44.19 515.71 51.33 438.86 Prob > chi2 .000 .000 .000 .000 R2 within .078 .078 .068 R2 between .638 .638 .658 R2 overall .558 .558 .572 Rho .679 .679 .553 Baltagi-Wu LBI N 1.92 130 130 130 130 Note: cells present coefficients followed by standard errors in parentheses. a+ p<.10, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 33 .3 -.1 -.1 0 0 .1 .1 .2 .2 Figure 3. Marginal effect of DAS party membership and Total number of DAS on the Proportion of STAs 95% CI 0 .2 .4 DAS party membership (%) Note: other variables are hold at their means .6 0 10 20 30 40 Total number of DAS 50 34

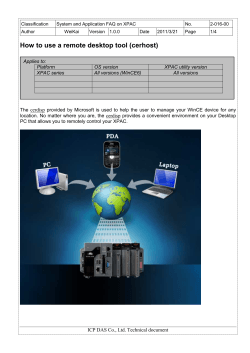

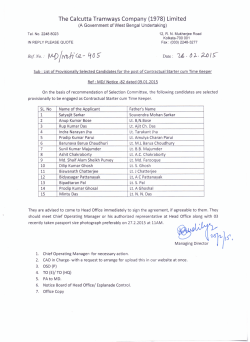

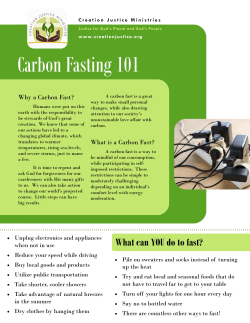

© Copyright 2026