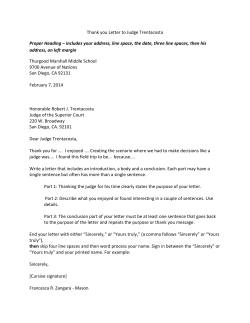

Full Article. - University of Miami Law Review