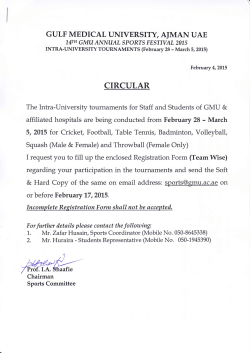

Sports Illustrated - April 6, 2015 USA