on 0

MALAYAN FOREST RECORDS

No. 16

FORESTERS' MANUAL OF DIPTEROCARPS

by

C.F. SYMINGTON

PERPUSTAKAAN

NEGARAMALAYSI

A

Penerbit Universiti Malaya

Kuala Lumpur

Malaysia.

CONTENTS.

PAGE

I

.. .

Introduction

.. .

.. .

•

...

1

Part 1•

Geological history and world distribution of the dipterocarps ...

VI

Ecological distribution of the dipterocarps in the Malay Peninsula

..

X11

...

xxv

.. .

••

XXXVll

...

...

XXXVllI

Field observations of dipterocarps .. .

List of forest reserves

Part II

.. .

...

. ..

• • •

.. .

Keys to groups of Malayan Dipterocarps

A.

Field key based mainly on bole and bark characters

B.

Key based on flowers

.. .

.. .

.. .

...

c.

Key based on fruits

.. .

.. .

.. .

...

..

XLll

Part III

•

XLi

Specific descriptions arranged in natural groups

•

I.

..

11.

...

lll.

•

IV.

.. .

.. .

.. .

.. .

1

· ..

.. .

...

4

.. .

. ..

27

The Meranti Damar Hitam group of Shorea

.. .

The Red Meranti group of Shorea

· ..

.. .

44

58

The Genus Shorea

The Balau group of Shorea

The Meranti Pa' ang group of Shorea

The Genus Parashorea

.. .

.. .

.. .

.. .

97

The Genus Pentacme

· ..

· ..

..

.

.

.. .

· ..

.. .

.. .

The Genus Balanocarpus

.. .

.. .

· ..

.. .

lX.

The Genus Dipterocarpus

.. .

· ..

· ..

. ..

x.

The Genus Dryobalanops

· ..

.. .

.. .

.. .

The Genus Anisoptera

· ..

· ..

· ..

.. .

104

108

147

153

191

199

The Genus Vatica

· ..

.. .

· ..

· ..

.. .

211

.. .

· ..

.. .

232

Bibliograpby

...

· ..

.. .

.. .

287

Index to Scientific Names

· ..

.. .

.. .

.. .

241

Index to Vernacular Names

·..

.. .

"

.

.. .

243

v.

•

Vl.

..

Vll.

...

Vlll.

•

•

Xl.

..

xu.

...

Xlll .

PERPUS

T

A

K

A

A

N

..

NEGARAMALAYSI

A

The Genus Hopea

The Genus Cotylelobium

•

PART I

GEOLOGICAL HISTORY AND WORLD DISTRIBUTION OF

THE DIPTEROCARPS

It is well known that the forests of the Malay Peninsula are very closely

related, ecologically and floristically, to those of Borneo and the other islands

of the Sunda Shelf!, and that many typically Malayan genera occur as far off

as India, Ceylon, the Philippines, and New Guinea. Thus to complete a study

of the Malayan flora, and particularly of the Dipterocarpaceae, the most typical

family of our jungle, reference is necessary to the literature of many adjacent

territories. The following brief review of the history and distribution of the family

emphasises the relative or potential importance of these territories as sources of

information.

It will be seen from text-fig. 1 that the Dipterocarpaceae are distributed

over a large area of tropical Africa and the Indo-Malayan region from India to

New Guinea, embracing territories separated by sea barriers; further, that Borneo

and the Malay Peninsula are much the richest in species. From the latter fact

it is reasonable to infer that Borneo, or adjacent land now under the sea, was the

original home of the family.

The family has radiated from its place of origin but sea, mountain, and

climatic barriers, and, possibly, human influences have inhibited an evenly graded

distribution. Dipterocarps are not adapted for dissemination over wide distances

by wind. and water-distribution, although not unknown, "cannot be regarded as

ancestral in the family" (1, p. 87) . Therefore, to eXl'lain the extent of their

present distribution, it must be assumed that land bridges existed between territories now separated, while the absence or severance of land connections has

limited distribution.

Climatic baniers have also played an important part in determining thc·

distribution of the family. Dipterocarps are essentially tropical evergreen rainforest trees, biologically unsuited to life under less warIll and uniformly moist

conditions. In their natural habitat, they disappear on mountain slopes at an

altitude of 3,000-4,000 ft, and higb ranges form impassable baniers. A few

species have been evolved, however, capable of withstanding periodic desiccation,

and well adapted to life in monsoon climates. Shorea robusta, the sal of India .

and Shorea Talura, which occurs in the north of the Malay Peninsula, are example:;

of such xerophytic species; both can survive intermittent fire and the former even

frost. They, or similar adaptable forms, have probably been responsible for

bridging climatic baniers to the lands now inhabited by the furthest outpost5

of the family. In very recent geological times man has created many local barriers

to the spread of dipterocarps by replacing the rain forest complex with cultivation, or forest of a more xeropbytic type in which few dipterocaxps can live.

PERPUSTAKAAN

NEGARAMALAYSI

A

1

•

VI

The Sunda Islands are Borneo, Sumatra, Java, and the lesser intervenin~ islands sud.

as Billiton and. Bangka, and the N atuna, Rhio, and Lingga archipelago!'. They are

situated upon a continental (Sunda) shelf and separated by shallow seas .

..

YU

. : •• . . . . . . '"

,."

I

•

Chi na

VI

ndi a

{lfls/obie 6rt4

6/4

,'II'•••••

"

I

I

'.

'.

,

,

",

A rlt.a,

t/~ \

I

\

\

It_.

".

\

\

\

\

\

,,

~5Id/it

\,

(ontinenM soe¥

\

\

\

I

(5Dnd6SliefJ

I

PERPUSTAKAAN

u5trali~

NEGARAMALAYSI

A

/

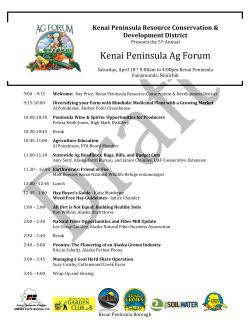

Text.fig, I. - World distribution 01 the Dlpterocarpaceae

(The 6gures after the names of twitories give the number of genera and species represented; for India 6/4should read 6/14,)

GEOLOGICAL HISTORY AND WORLD DISTRIBUTION OF THE D1PTEROCARPS

•

-

The geographical distribution of the family is intimately connected with

the geological history of the regions in which the family is at present represented,

or where it may be assumed to have occulled. This geological history has been

reconstructed largely on the basis of fragmentary evidence and many of the conclusions to be drawn are admittedly speculative. Recorded dipterocarp fossils

are not numerous and they throw little light upon the earliest development of

the family. The more sensational claims, said to prove that. dipterocarps occurred

during the Upper Cretaceous in North America and England, are now discredited

(1, p. 83). Acceptable evidence does little more than prove that the family was

well established within its present territorial limits towards the end of the Tertiary

period, and it is suunized that the family orginated in south east Asia in the late

Mezozoic or early Tertiary times (43, p. 6).

At this period, some 70 million years ago, the Sunda Islands were united

to one another and to the Malay Peninsula, forming an extension of the Asiatic

continent known as Sunda La.nd. To the east was another land mass, which is now

the Australian continental shelf canying New Guinea. Between these two continents lay an orogenetically active, unstable area in which archipelagic conditions

obtained (43, p. 14).

Because of the fonner existence of Snnda Land we would expect to find

that, originating in or near western Borneo, the dipterocarps are best represented

in the islands cf Western Malaysia l and the Malay Peninsula. On the whole

this is so: Borneo, with 13 genera 2 and 276 species, has the best representation,

but the Malay Peninsula (14 genera and 168 species), Sumatra (12 genera and 72

species~), and the intervening islands are also rich.

Java has only 5 genera and

10 species. This can be expla.ined by assuming that Java became separated from

the Asiatic continent at a much earlier date than Borneo, Sumatra, and the other

Sunda Islands, but it must not be overlooked that the primary jungle of Java

has been almost completely destroyed below 3,500 ft, and fossil evidence suggests

that the island once supported a richer dipterocarp flora than it does today.

1

East of "Wallace's line " a so iking change in the richness of the dipterocarp flora is evident: one passes suddenly from dipterocarp-forests to forests in

which only a few migrants appear. In the vast archipelago of Eastern Malaysia,

from Celebes and Lombak to New Guinea, only 4 genera (none endemic) and 9

species have been recorded, and there is reason to suppose that subsequent exploration will not greatly alter these figures. This provides convincing proof that

Eastern and Western Malaysia have been separated from an early age: the few

groups that have spread to the east have done so, most probably, along temporary

land bridges via the Philippines.

PERPUSTAKAAN

NEGARAMALAYSI

A

Western Malaysia is the term given to the Malayan region west of the east coasts of

Bo:-neo and Bali: Eastern Malaysia includes the islands of Celebes, Lombak, Sumba,

Ceram, Timor, New Guinea, and others that lie to the east of thLs line. The Philippines

are usually considered a separate, intermediate area. The dividing line between Western

and Eastern Malaysia is "Wallace's line".

I The groups of Shorea and the two major subdivisions of Hopea have

been treated as

separate genera.

, It should be remembered that Sumatra has been relatively little explored: the true figure!;

would undoubtedly be much higher.

1

..

.

VUl

-~-

;

-

1

-

•

1

-

-

-

1

3

-

-

5

-

1

6

3

3

2

2

2

-

-

-

-

I

I

-

-

3

I

1

5

I

-

-

-

I

I

11

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

9

4

-

11

-

7

-

2

I

-

1

1

1

1

1

3

35

-

7

9

•

9

5

J

49

2

-

28

21

-

6

2

2

29

7

-

I

-

-

-

1

-

1 -

5

5

-

.-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

1

1

1

U

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

U

-

-

-

-

-

15

-

1 11 5

10

-

-

-

1 -

-

-

-

-

Vl

<:::

-

-

-

-

Q

0

0

<:::

cO

-

~

0.

::s

<:::

oS

0

on

0.

0

3

4

4

11

5

13

12

14

-- - - - -

10

10

2

2

10

6

1

2

0

10

-

-

-

-

-

-

3

oS

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

31

<:::

0

0

oS

"'0.

<::: 0

...

bOb<

.. .,

•

species listed (109, p. 516) .

• This excludes the territory of Partani and NakaWI, Sritamarat, east of the Malayan-Burmese floristic division.

1

5

4

6

52

10

276

72

168

36

32

34

2

7

44

14

1

34

oS

0

0.

u

'"

."

.'"

8.

.""

...-... .-.. ..."'" "'"::s " -.."

E' -..... ...

.,...e'" ... ...

0

E-<

>'" >'" ~ ~ E-<

::s...

UI

-

3

1

-

U

2

1

-

-

-

>'"

0

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

«

<:::

2

Z

u

..0

0

.-

"

'

"

....

0

.0.

0

on

~

...

oS

a::s

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Q

i:'

..0

0

-''""

<:::

0

c

UI

..,

1)

34

11

I

5

J

-

2

11

-

-

Q

0.

....-"

0

...

['j

S-'"...

-

-

-

-I I

-

-

-

-

Q~

22

12

0 "

o~

~~ ~§

..0"

",

9

2

~oS

...

Ul 2

::s oS

""0

on <:::

'E 5

'"

"'::s

u""

~

_.. e'" . .

0

--"'"

u

UI

~

2

\

3

3

2

1

I

1

3

I

2

-

-

-

3

-

7

1

f.tl

..0

P

0.

0

~

~

.-il<

...~...

u

-

-

-

-

-

il<

.,

<:::

...~

"

A

Hopea

The oriJtinal, Indian species of Balanocarpus are inclnded in the Euhopea group of Hopea. The anomalous species iJ. b,.e'/IIpeholans (Thw.) Alst. and B. Heimii King are listed under Balanoca,.p~ although they have no real claim to the name.

• The African genera Monotes ahd M.,,.qtus1a are badly in need of systematic revision .....hich will probably reduce the number of

...

New Guinea

•••

Celebes

•

•••

Philippines

••

-

•• •

Moluccas

-

1

Java

2

-

13

22

•• •

Borneo

5

63

25

4

4

•••

23

8

Sumatra

10

10

IS

I

-

-

Malay Peninsula

••

6

•

-

-

4

2

-I

-

6

-

-

-

-

-

-

1

-

--

-

-

Po<

...

cO

.;;;

<'d

0

\"l...

-I -

-

-

-

p::;

"t:I '"'

QJ btl

0

3

ThailaQd'

• ••

u ~

~

v

1-0 ~

I

bIJ

3

4

-

-

2

-

~

QJ

-

~

..

~._

0

~...

~

-

Indo-China

\

~ ~::s

<:::::S

<:::

+= S

'';::; Cl.

bO

China & Hai.nan

•••

...

QbO

-

Burma

.

0

Andaman I slands

•

•••

India (Western

Peninsula)

••

•••

-Seychelles

Ceylon

'"

Africa'

•

b<

A

""

.......

"

~

Eo

-...

..

::s

""... il<

e

r-

~

Shorea

W orld distribution of genera and species of dipterocarps

PERPUSTAKAAN

NEGARAMALAYSI

A

-

GEOLOGICAL HISTORY AND WORLD DISTRIBUTION OF THE DIPTEROCARPS

,

..

,~

I14

,I

•

The Philippines, with 11 genera and 52 species, have a good representation, yet are much poorer than Borneo, and have no endemic genus. This suggests, and there is abundant biological and oceanographic evidence to support the

suggestion, that free inter-migration of plants or animals between Borneo and

the Philippines has been impossible since early geological times, but that intermittent infiltration has occurred along temporary bridges formed by the Palawan

and Sulu island chains.

In the early Tertiary period when the Dipte1'oca1'par;eae were spreading

east and south over what was then Sunda Land the family was also spreading

to the north and west. It reached Indo-China and Thailand, and thence, via

Burma and what is now the Bay of Bengal, reached the western peninsula of

India and Ceylon. In the passage it encountered climatic baniers but these were

apparently surmounted by the evolution of species adapted to adverse climatic

conditions.

Study of the present-day distribution of the dipterocarps in the lands to

the north of. the original home of the family reveals this striking fact:

there is

a sudden decrease in number of genera and species beyond the Malay Peninsula.

The Peninsula has 14 genera and 168 species, whereas in the whole of Thailand,

Indo-China, and Burma there are only 10 genera and 37 species. In the last

three tenitories there are extensive areas of deciduous or semi-deciduous forest,

but these forests are largely of recent biotic origin and there is no reason to suppose

that they have always fonned extensive baniers to free migration of dipterocarps.

In Thailand, Indo-China, and Burma there are still large areas of tropical lowland evergreen rain-forest, as suited to dipterocarps as the forests of the Peninsula, but surprisingly few species of dipterocarps occur in them. A possible

explanation of this is that the melting of the ice of the Pleistocene glacial period

caused a rise in the sea level reducing the Peninsula, in Miocene times, to an

archipelago, and separating it from the mainland of Asia (99, p. 186). There

is strong support for this theory in biological evidence and in the existence of

raised beaches. Subsequent elevation restored the connection with the mainland

and fOIlIled the Peninsula of today, but the results of long separation are very

evident in the flora of the Malay Peninsula and the tenitories adjoining it to the

north.

The line of separation between continental Asia and the Malay Peninsula

is said to have run from the mouth of the Kedah river (near Alor Star), northwards to Singgora on the east of peninsular Thailand (108, p. 79). This is

supported by the evidence of dipterocarp collections. Thus, Pattani and part of

Nakawn Stritamarat in Thailand belong to the Malayan side, while Perlis, Langkawi,

and a little of the north west of Kedah belong to the Burmese side of what may

be called the Malayan-Buxmese floristic division. A comparison of the dipterocarp flora of Gunong Jerai (Kedah Perak), just south of this division, with Gunong

Raya on Langkawi, just to the north, is striking. Gunong Jerai has at least

$} genera and 29 species: Gunong Raya has only 5 genera and 11 species.

PERPUSTAKAAN

NEGARAMALAYSI

A

x

GEOLOGICAL HISTORY AND WORLD DISTRIBUTION OF THE D1PTEROCARPS

•

Climatic barliers limit the distribution of the Dipterocrupaceae in the north

of Indo-China, Thailand, BUlIIla, and India. One Hopea in Kwabgtung, and

one Vatica in Hainan, represent the outposts of the family to the north east, while

the famous sal (Shorea robusta) has penetrated north-westwards far beyond the

range of other species into the dry forests of the Punjab.

In the rain forest of the western peninsula of India there are 6 genera

and 14 species, all essentially Malayan except one species of Vateria. In Ceylon,

however, there are 10 genera and 44 species, two of the genera, Doona and Stemonoporus, being endemic. This remarkable development of the family in Ceylon

has not, as far as I am aware, ever been adequately explained, but the appearance

of endemic genera is consonant with the separation of that island from the mainland in early Pleistocene times

West of India and Ceylon no Malayan group is represented, but in the

Seychelles there is the monotypic endemic genus Vateriopsis, which appears to

be a derivative of the Indian Vateria, and in Africa there are two remarkable

genera Monotes and Marquesia. These African genera differ in many respects

from the true dipterocarps, in particular in the absence of resin-ducts in the wood

(109, p. 516), and it has been questioned whether they should be included in

the family at all. The author of the most recent authoritative account of these

genera (109) considers that they should be retained jn the family but placed in

a separate sub-family, the Monotoideae.

The Monotoideae are small trees of savana forests. they are of little economic

importance but they have received considerable attention from botanists. It is

interesting to speculate on how these dipterocarps, if dipterocarps they are, have

anived in AfIica. It has been suggested that they reached that continent from

south India via the Seychelles and Madagascar, but the biological evidence is

against this, no dipterocarp or dipterocarp fossil having been coHected on the

latter island. The explanation of Bancroft (1, p. 97), that they followed the

north west land passage between India and Africa is the more probable, although

it involves the assumption that the climate of this land connection was at some

distant time much less arid than it is today. The discovery of fossils with dipterocarpaceous affinities on Mt Elgon in Uganda supports this theory, and suggests

that the family was formerly more widely represented in Africa than it is at the

present time .

PERPUSTAKAAN

NEGARAMALAYSI

A

•

Xl

ECOLOGICAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE DIPTEROCARPS

IN THE MALAY PENINSULA

1

The Dipterocarpaceae is the predominant family of timber trees in the tropical

lowland evergreen rain-forest of the Malay Peninsula. These forests, in which

most of the commercial timber exploitation occurs, constitute the main climatic

climax vegetative fOlmation of the country. Dipterocarps also OCCur in certain.

edaphic and biotic fOlmations of limited extent, some of which are of considerable

economic importance.

As an ecological classification of the vegetation of Malaya has not yet been

published a brief review will be given of the main types of forest with special

reference to those in which dipterocarps occur. A colloquial. nomenclature of types

has been adopted but wherever possible the equivalent names in Burtt Davy's classification of tropical woody vegetation-types (16) are given.

THE MAIN (CLIMATIC) CLIMAX FORMATIONS

1. The lowland dipterocarp-forests.

These would be included in Bm tt

Davy's tropical lowland evergreen rain-forest fOIl nation. The bulk of the exploitable forests of the Peninsula are in this category, which embraces all the welldrained primary forests of the plains, undulating land, and foothills up to about

1,()()0 ft altitude. In most localities the dipterocarps form a high proportion of

the emergenP and dominant strata of the forest. Exceptionally, dipterocarps may

be almost absent, and occasionally, over small areas, they may be so abundant

that large trees of other families are few and scattered. A compilation of figures

from enumeration surveys, covering 7,900 acres of jungle mainly of lowland and

hill dipterocarp forest types, was made in 1930. This revealed that the average

figures per acre were: 22 trees of 12 in. diameter and over, and 2,085 cu. ft round

timber, of which 6.53 trees, and 1,158 cu. ft were dipterocarps. That is, 30 per

cent. of the trees by number and 55.5 per cent. by volume, were dipterocarps.

It will be appreciated, however, that these percentages would be much higher were

only the larger trees included.

In these lowland dipterocarp forests about 130 species of dipterocarps, representing all the main groups, occur, but in anyone district it is doubtful whether

there are more than 60 species, and the representation of groups may be incomplete.

In anyone reserve there may, exceptionally, be as many as 40 species, but between 10 and 30 is a more usual number.

In most lowland reserves the Red Meranti group is represented by 2 or 3

species, and is the most conspicuous woody component of the jungle. Usual1y

one or two species of Dipterocarpus (kerning) are present, and occasional1y, as in

parts of Negri Sembil.an and south west Pahang, keruing is considerably more

abundant, both specifically and in volume of timber, than Red Meranti. Dryobalanops aromatica (kapur) predominates in many areas in eastern Trengganu.

Pahang, and Johore, and at Kanching in Selangor, but elsewhere it is absent (Text-

PERPUSTAKAAN

NEGARAMALAYSI

A

•

I

Emergent trees are "isolated trees whose crowns rise above the general canopy. They

are clearly dominant in the silvicultural sense, but not in the ecological sense, they can

exercise no general controlling influence on the forest" (57, p. 227).

••

XII

ECOLOGICAL DISTRIBUTIO

OF THE DIPTEROCARPS IN THE MALAY PENINSULA

fig. 96). The important Balau group is not invariably represented in the lowland

dipterocarp forests, but it is rarely entirely absen i: from any considerable area.

Chengal (Balanocarpus Heimii) is very local in distribution, being entirely absent

from large tracts and common in others (text-fig. 81). Hopea and Vatica are

rarely absent from any considerable area, and occasionally one or more species

may be common, but the gregarious tendency of Hopea is Ilfore marked in the

hill diptero<>arp-forests. The Meranti Pa'ang and Meranti Damar Hitam groups

of Shorea, and Anisoptera, are represented in most areas and, occasionally, these

ShoTea groups may be as abundant or more so than Red Meranti.

The dominants in each stratum of these luxuriant rain-forests are segregated

and grouped so that they form an almost unlimited number of different plant

communities. Obscure local climatic or edaphic variations may influence the distribution of species but it is more probable that the main determining factors are

chance and opportunityl . Some of these communities are floristically very distinct

from others, yet they are essentially similar in rank.

In the extreme north-west of the Peninsula the floristic composition of the

dipterocarp forests is str ikingly different from that of the rest of the Peninsula.

The dividing line, which is quite an abrupt one, has already been referred to

(p. x) as the "Malayan-Eunnese floristic division". The precise location of the

line is difficult to detect, because much of the ar ea is now cultivated and inhabited

by forest of a secondary character, but it passes approximately from the north

of the Kedah river , northwards to Singgora on the east coast of peninsular Thailand. To the east of this line the species represented in virgin jungle are predominently Malaya n ahd dipterocarps are numerous; to the west of the line there

is no marked difference in physionomy of the virgin jungle, but the species are

predominantly Bunnese and there are fewer species of dipterocarps. In this

"Bur mese" area the R ed Meranti and Meranti Damar Hitam groups are absent,

the Balau group is poorly represented, but the Meranti Pa'ang group is better

represented, both in nu mber of species and individuals, than in any other part

of the Peninsula2 • Only sma:H areas of virgin jungle of this "BuIIllese" type

remain in the political division known as the Malay Peninsula, most of them having

been cleared for cultivation, or converted by cutting and fire into the secondary

Schima-bamboo forests described later.

2. The hill dipterocarp-fore sts.

These are also included in Burtt Davy's

PERPUSTAKAAN

NEGARAMALAYSI

A

- 1 So var ied flori stically are the communities that comprize our lowland dipteroca rp f orests

that fundamental subdivisions have not been detected. It has not been found possible

to subdivide these forests into associations or consociations but I have found it COllvenient to apply to the various communities encounte red the te rm associatiun-scgregate.

This term was p'roposed by Braun (7), in 1935, t o desig nate communities in thc mixed

deciduous fo rests of N orth America th at a re o f essentiall y equivaien t ra nk. although

often floristically quite distinct.

, The following species have been recorded west of t he Malayan-Burmese floristic division:

S. Guiso (membatu), S. assamica, f. globife ra, (meranti pipit), S.? fannase .

S. hypochra (meranti temak), S. serice·i flora (merant i jerit), S. T alura (temak); Para'

shorea Lucida (geru~) ; Hopea f errca (malut), H . iatifolia (mc rawan daun bulat), H.

odorata (chengal pasir), Dipterocarpus Baudii (keruing bulu), D. chartaceus (keruillg

kertas), D . costatus (keruing bukit) , D . Dyeri (keruing atoi), D. gracilis (ker uing kesat),

D . grandiflorus (kerning belimbing), D . K crrii (keruing gondol), D . oM"sifo iitls ; .1I1iso/,·

tera sp. (mersawa); and Vatica cinerea (resak laut) .

..

,

Xlll

•

~ '-

© Copyright 2026