ânew destinationsâ and immigrant poverty1

“NEW DESTINATIONS” AND IMMIGRANT POVERTY1 Mark Ellis, University of Washington Richard Wright, Dartmouth College Matthew Townley, University of Washington INTRODUCTION The 1990s and 2000s saw the spatial diversification of immigration to new destination states away from the Southwest, West, and Northeast to the Plains, the South, and East. Some states recorded a doubling and tripling of populations; some counties grew at even higher rates (e.g., Li 2008, Massey 2008, Light 2006, Zúñiga and Hernández-León 2006. Dispersion to suburbs and rural areas was an allied dimension of these new immigrant geographies (Singer et al. 2008, Jones 2008). Crowley et al. (2006) report that immigrants, including Mexicans, who lived in these new destination areas in 2000 had lower rates of poverty than immigrants in traditional gateway regions.2 This difference could be because the economies of these new destinations were more vibrant than in traditional gateway regions. Or it could be because the immigrants who lived in new destinations had different characteristics than those in traditional gateways that enabled them to escape poverty more readily. Or it could result from a geographically variable combination of these two factors. What happened to the geography of immigrant poverty in the 2000s? One possibility is that the differences between traditional gateway and new destination immigrant poverty rates remain as they were in the 2000. Alternatively, these differences could have widened if immigrants in new destinations continued to fare even better than those who lived in traditional gateways. Or perhaps the slow economic growth of the early 2000s and massive recession of the late 2000s affected almost all locations and compressed the variation in poverty rate across space. 1 National Science Foundation grants BCS-0961167 and BCS-0961232 provided partial funding for the research reported in this paper. This is a draft version of a paper prepared for the National Poverty Center, University of Michigan conference on Immigration, Poverty, and Socioeconomic Inequality, held at UC Berkeley, July 14-15. 2 They report exceptions to this trend, however; rural areas in new destination regions recorded relatively high poverty of poverty. 1 Whatever these geographical changes may be they unfolded against a backdrop of diverging trends in immigrant versus native poverty rates. In 2007-9 the national immigrant poverty rate stood at 16.4%, a 1.5 percentage point decline since 2000. The national native born poverty rate rose by 1.5 percentage points to 13.3% over the same period.3 Thus, although the poverty rate remains lower for natives than immigrants, these rates began to converge in the 2000s. In raw numbers, the percentages correspond to 6,164,679 immigrants in poverty in 2007-9, an increase of 10.9% from 2000; and 34,280,367 native-born persons in poverty, an increase of 16.5%. There is little doubt that the deteriorating economic picture has played a role in the rising numbers of people in poverty. Immigrants appear to have weathered the storm better than the native born, especially when one factors in the faster growth of the foreignborn population during the 2000s – something we do explicitly later in the essay. This paper answers three interlinked questions on the geography of immigrant poverty, each of which is framed within the general context of the diverging national trends in poverty rates just described and the emergence of new immigrant destinations: 1. Does the pattern of lower poverty rates in non-traditional destinations for the 1990s persist into the 2000s? 2. Why do immigrant poverty rates vary geographically? Specifically, is this variation due mostly to local area economy effects or to geographical variations in immigrant characteristics, such as education, that affect the likelihood of being poor? 3. Between 2000 and the most recent period for which we have data, how have a) local area economy effects and b) the spatial variation in immigrant characteristics changed the geography of immigrant poverty? BACKGROUND Immigrants are more likely to be poor than the US-born. For example, in 2000, 17.9% of foreign-born persons were below the federal poverty line compared to 11.8% of nativeborn persons. Immigrants are poorer than the US-born for multiple reasons but the major causes of their higher poverty rate are their disadvantageous socio-demographic characteristics (human capital) and the types of jobs they hold. A simple comparison with the US-born on mean years of education reveals that today’s immigrants on 3 Throughout the paper the data sources for the poverty calculations and all other variables are the 2000 PUMS from the 2000 decennial census and the 2007-9 three year PUMS from the American Community Survey, unless otherwise indicated. 2 average are less educated than the native born (Borjas, 1999). This difference occurs in part because a disproportionately large share of immigrant adults, especially from Mexico, lacks the equivalent of a high school degree. This educational disadvantage plus poor English language skills places a large fraction of the contemporary immigrant workforce at risk of low-wage employment regardless of the sector in which they work. In addition, and partly because of their poor qualifications, many immigrants work in highly competitive employment sectors, such as agriculture, non-durable manufacturing, and personal service work, where wages are especially low and prospects for advancement minimal (Waldinger and Lichter 2003). Poverty among immigrant groups varies considerably (Iceland 2006). Latino immigrants, who are mostly Mexican, tend to have higher rates of poverty than do immigrants from Asia. On average, the poverty rate for Asian immigrants is quite similar to that for the native born. Some Asian immigrant groups, however, have higher-than-average poverty rates, such as refugee groups from SE Asia. Over time as immigrant human capital improves their poverty rates tend to fall in line with assimilation theory’s expectations. Despite the narrowing of these gaps, some immigrant groups remain at greater risk of falling below the poverty line in a pattern that mirrors the native-born groups they most closely resemble. Because immigrants tend to be poorer than the native born, and because of concerns that recent immigrants are even more disadvantaged in human capital relative to the US-born, some commentators see the growing presence of foreign-born populations in the country as elevating overall US poverty rates (Borjas 1990). On initial inspection, data from the most recent decade hint at an association between rising poverty and immigration. Between 2000 and 2007-9 the overall US poverty rate increased from 12.5% to 13.7% and the foreign-born share of the population grew from 11.1% to 12.6%. Some trends in the 2000s, however, suggest that factors other than a growing foreign-born population are more significant drivers of poverty dynamics. In the 2000s the immigrant poverty rate declined from 17.9% to 16.4%, which reduced the share of immigrants in the poverty population from 16.1% to 15.2%. Thus immigrants are a disproportionately large share of the poor population at the end of the 2000s as they were at the start of the decade, but that fraction is declining. Rising native-born poverty rates - 11.8% in 2000 increasing to 13.3% in 2007-9 - rather than increased numbers of immigrants is the major cause of increased overall poverty since 2000. This finding becomes even clearer from a simple counterfactual. If we roll back the foreign-born percentage of the population to that found in 2000 - effectively making the assumption that the immigrant population did not grow faster than the native-born population after that date - and assumed 2007-9 poverty rates for the native- and 3 foreign-born populations, then the overall US poverty rate in 2007-9 would have been 13.6%.4 Thus, without any increase in immigration in the 2000s, the US poverty rate would have been a tenth of a percentage point lower than the actual rate – a marginal difference. Of course, this simple procedure does not take into account changes in the characteristics of immigrant and native populations that may affect their odds of being poor; nor does it account for changes in the geography of these populations that may alter their exposure to poverty-generating local economic conditions. We factor in the effects of these changes later in the chapter. The Geography of Poverty The odds of being poor vary considerably across the country and this variation is visible at multiple spatial scales. In some counties in the south, poverty rates exceed 30% in 2008 (e.g., Perry County Alabama). In Connecticut, in the same year, poverty rates were at or below 10% in all its counties.5 In general, poverty rates tend to be higher in rural and small metropolitan area than in the larger metropolitan areas, and cutting across these urban hierarchy differences, they tend to be higher in the south (Glasmeier et al 2008). Within large metropolitan areas, lower overall poverty rates disguise clusters of high poverty neighborhoods in central city and suburban locations (Cooke and Marchant 2006). These areas of concentrated poverty have generated considerable interest over the last three decades because of the ways in which the clustering of poverty exacerbates poor people’s disadvantages (Jargowsky 1997). Spatially concentrated poverty declined in the 1990s as overall poverty rates fell, but rose in the 2000s in line with increases in overall poverty rates (Kneebone and Berube 2008). Neighborhood concentrations of poverty within cities arise because of the segregating effects of income disparities combined with structural racism. At broader scales, such as counties and metropolitan areas, spatial variations in poverty rates reflect a combination of unfolding local economic circumstances – sectoral employment mix, exposure to the forces of global competition, and economic restructuring more broadly 4 The counterfactual poverty rate is calculated as follows: pc = ifitqit+1 where fit is the fraction of the population in category i (native born, foreign born) in time t (2000) and qit+1 is the poverty rate for persons in the same categories at time t+1 (2007-9). This experiment assumes that growing immigrant populations do not affect native-born poverty rates through increased labor market competition. Raphael and Smolensky (2009) report that such competition effects on native-born poverty rates are negligible. 5 These county poverty rates come from the 2008 US Census Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates available at: http://www.census.gov/did/www/saipe/data/statecounty/data/2008.html 4 - and the socio-demographic characteristics of residents, including their race, education, age, and family structure. As one might expect, these people and place effects are not independent; workers who are able to do so will adjust to unfavorable local labor market circumstances by migrating; capital will respond by redistributing resources to locations where human capital is more favorable. In any event, the map of poverty is not a cartography of “lassitude,” as Kodras (1997) pointed out in reaction to Reagan administration claims that poverty stemmed from laziness and ignorance, rather than the social and economic marginalization people face in their communities. Geographies of poverty arise from the conjunction of economic conditions and population structures in particular places (Lawson et al. 2010). Migration can occur for reasons unrelated to differentials in economic opportunity, such as moving for family reunification or to be near certain cultural and environmental amenities. Differentials in labor market conditions though are perhaps the most significant factor in population mobility. Workers move from locations where economic circumstances are unfavorable to places where there are better employment opportunities and higher wages. In line with expectations from the human capital theory of migration, those who are most responsive to these labor market signals tend to be the young and those with higher levels of education – groups who generally have the most to gain from an investment in relocation (Sjaastad 1962). Those who are older and those with the least education tend to stay put, which means the outmigration response to any deterioration in local economic conditions tends to be lowest among those most at risk of being poor to begin with. Moreover, when the less skilled do move they tend not to choose locations with the best prospects for long-term growth, which further distinguishes their mobility response from those with more education (Clark and Ballard 1981). Some literature suggests that the poor migrate in response to state and locality differentials in welfare. These effects are, however, marginal in relation to the volume of migration (Allard and Danziger 2000, Frey et al. 2006). In general, staying put may be the best option for the poor given the risks associated with moving to an unfamiliar place and after considering the benefits that potentially accrue from the social support networks of family and friends in the current location (Clark 1983). New Destinations Social networks are also at the center of explanations for why immigrants to the United States tend to cluster in relatively few locations – or at least did until the last two decades. Networks channel information from immigrants to prospective migrants in the home country (Boyd 1989; Massey 1990). Those who elect to move to the US use this information to follow in the footsteps of family and friends. Pioneering immigrants who move in response to economic opportunity or recruitment by employers establish the outlines of an immigrant enclave; those who follow may also be responding to those 5 economic pulls, but the cumulative causation process of migration works to channelize later arriving newcomers to the enclave well after the initial economic pull that attracted the initial arrivals has weakened. Consequently, US immigration in the last half century has been experienced mostly in a handful of states – California, New York, Texas, Florida, and Illinois – and within those states disproportionately in the largest metropolitan areas. In this respect, late 20th century immigration differs in regional orientation from the last great inflow in the early 20th century (more southern and western now; more northeastern and midwestern then) but resembles that wave by being a largely big city phenomenon. Over the course of the last two decades, this concentration in a handful of states and their major metropolitan areas began to weaken as the foreign born began to settle in multiple locations across the country (Singer 2004). Explanations for this dispersal group into four categories. First, shifts in labor and housing market conditions made older gateways less attractive relative to new destinations (Card and Lewis 2005). For example, the 1990s saw weak labor demand and higher-than-average housing costs in places like southern California whereas new destination regions were cheaper to live in and had booming economies. Light (2006) argues these conditions were part of an emerging regulatory environment in southern California that was unfriendly to continued immigration. Second, initial settlers in new destinations laid the foundations for others to join them in emerging enclaves via networks. Growing immigrant populations in new destinations increased enclave vitality in these places, which in turn attracted more immigrants (Leach and Bean 2008). Three, by the 1990s a maturing immigrant population had sufficient socioeconomic and cultural experience in the US for some to leave gateway enclaves to seek opportunities elsewhere – a process that operated both within and between cities (Ellis and Goodwin-White 2006). And, fourth, the growth of border and immigration enforcement in the southwest in the 1990s encouraged new arrivals to go elsewhere (Massey and Capoferro 2008). Despite the rural character of some new immigration to the US, this dispersal has generally been associated with large metropolitan areas. Immigrant settlement thus remains a large metropolitan area affair even while the largest gateways – New York and Los Angeles – have lost some share. In 2000, 76.7% of immigrants lived in the 49 metropolitan areas with populations of a million or more. That same set of 49 metropolitan areas - those over one million in 2000 - captured 75.4% of all immigrants in 2009. Thus smaller metropolitan areas and rural areas gained shares of the immigrant population in the 2000s but their share of immigrants remains small – only 14.6%. The fact that only 51.6% of the native-born population lived in those 49 metropolitan areas in 2009 further highlights the large urban area bias of contemporary immigrant settlement. 6 A geographical analysis of immigrant poverty would thus gain most from paying particular attention to metropolitan areas of one million or more; the places where most immigrants live. Our investigation of the geography of immigrant poverty additionally categorizes these large metropolitan areas by immigrant gateway type using Singer’s (2004) classification scheme. Her taxonomy identifies six classes of gateways: three older gateways (Former, Continuous, Post-WWII) and three new destination gateways (Emerging, Re-emerging, Pre-emerging). This gateway typology allows us to determine whether immigrants are better off – less likely to be in poverty in new destinations than traditional gateways. Table 1 lists criteria for membership in each gateway type and lists metropolitan area in these categories. The set of metropolitan areas we use is almost identical to that used by Singer but differs in one respect. We consolidated the constituent metropolitan areas of New York classified as Continuous gateways (e.g., Bergen-Passaic) into the aggregate New York CMSA. And because not all metropolitan areas of greater than one million are immigrant gateways, we include a seventh residual category for these. As one might expect, the share of immigrants in these gateway types is changing (see Table 2 – upper panel). Continuous and Post-WWII gateways accounted for 51.3% of immigrants in 2000, dropping to 46.5% in 2009. Collectively, the three new destination gateway types – Emerging, Pre-emerging and Re-emerging – increased their share of the foreign-born population from 18.2% in 2000 to 21% in 2009. A few new gateways lost some of their appeal between 2007 and 2009, however. The fraction of immigrants in Re-emerging gateways dropped each year over this time period and the Emerging gateway share declined, slightly, between 2008 and 2009. Other large metropolitan areas registered small increases in immigrant percentage share in the 2000s but these places account for only 3.8% of all immigrants in 2009. Smaller metropolitan areas (less than 1m) and rural areas gain a relatively minor share (combined they account for 23.3% of immigrants in 2000 and 24.6% in 2009). To put this proportion in perspective, their share is roughly the same as that held by the four continuous gateway metropolitan areas of New York, Boston, San Francisco, and Chicago. Table 2 (upper panel) also lists native-born population share in the same categories. The biggest differences between them and the foreign born are in the top and bottom two rows of the table. Much smaller fractions of the native born live in Continuous and Post-WWII metropolitan areas than do immigrants. In contrast, as discussed above, there are much higher shares of the native born in small metropolitan and rural areas relative to the foreign born. 7 The lower panel of Table 2 illustrates the concentration of the foreign-born population in another way using location quotients (i.e., the share of the FB(NB) population in a particular category at time t divided by the share of the total population in that category at time t). If the foreign born were distributed across the country in proportion to the total population in each location – an “expected” distribution - then the location quotients (LQ) everywhere would have the value of one. The location quotients for the foreign born show high concentrations of immigrants (double or more of that “expected”) in Continuous and Post-WWII gateways. Emerging and Re-emerging gateways location quotients are smaller but still greater than one. All other gateway metros show relative concentrations of immigrants below one, although in all these cases the location quotient increased over the course of the decade; immigrant settlement gradually deconcentrated in the 2000s. The variation of location quotient values for the foreign born is much greater than those for the native born. Most LQ scores for the native born are within 10% of the “expected” value of 1.0. The nativeborn distribution moves out of this range only in Continuous and Post-WWII gateways, signifying the number of natives is less than expected in these places. GEOGRAPHICAL CONTOURS OF IMMIGRANT POVERTY Figure 1 plots overall poverty rates in 2000 and 2007/9 using the gateway categories introduced above. To capture variability in poverty rates outside large metropolitan areas this chart and all subsequent analysis subdivides the broad categories of small metropolitan areas and rural areas – the last two rows of both panels in Table 2 – by the four major census regions. The blue shaded portion of each bar is the fraction of the poverty population that is native born; the red-shaded portion represents the foreignborn fraction. Starting from the left, the bars are ordered by gateway category as in Table 2. The first two sets of bars are the traditional gateway metropolitan area categories; the next three sets are new (i.e. “emerging”) destination gateway categories; then come the residual gateway types for large metros. Finally, the four sets of small metropolitan area and rural area categories now appear, grouped by census region. US poverty rates are plotted for comparison purposes in the rightmost set of bars. Figure 1 shows two main things. First, following the national trend, poverty rates increased everywhere between 2000 and 2007-9 with one exception: Post WWII gateways. Second, increases in the native-born share of the poverty population is driving overall increases in poverty in several location types, a tendency most notable in new destination gateways and in small metropolitan and rural areas in the Midwest. In 8 Post WWII gateways, the drop in poverty appears to be mostly because of a decline in the foreign-born share of the poverty population. In addition, Figure 1 illustrates that poverty rates are highest in small metropolitan and rural areas in the south and west, which confirms existing findings about the geography of rural and small urban area poverty (Lichter and Crowley 2002). Furthermore, new destination metropolitan areas – Emerging, Pre-emerging, and Re-emerging gateways have lower poverty rates than traditional destination metropolitan areas (Continuous and Post-WWII gateways) in 2000. Between 2000 and 2007-9, however, poverty rates rose rapidly in all three new destination gateway types, leaving their poverty rates above that of the Continuous gateways and much closer to the level in Post WWII gateways by 2007-9. Table 3 confirms these impressions in two ways. First, it documents that the foreignborn share of the population in poverty – the second columns of the 2000 and 2007-9 panels – declined in Continuous, Post WWII gateways, and Re-emerging gateways. It nudged up slightly in Emerging and Pre-emerging gateways and in several other locations as well. Even in locations where the foreign-born share of population in poverty increased, however, the change is dwarfed by the increased share of the overall population that is foreign born. The third columns in each panel divide the percentage of the immigrant poor population by the percentage of the population that is foreign born - the second column by the first column in each panel. In all locations these ratios dropped between 2000 and 2007-9. These ratios show that across the country, regardless of location type, by the end of the 2000s the disproportionate concentration of the foreign born among the ranks of the poor remained but was smaller at the end of the decade than at the start. Building on this share perspective, we next explore how the rates of being poor changed for immigrants and the native born. Table 4 lists their poverty rates in each year and the percentage difference between them. Nationally, the poverty rate differential between immigrants and natives halved over the 2000s, a trend replicated more or less in all locations. This occurs largely because of substantial percentage increases in native-born poverty rates – see Figure 2. In some instances this convergence is accelerated because of declining rates of poverty among the foreign born (e.g., Continuous, Post WWII, and Re-emerging gateways, plus small metropolitan and rural areas in the west); in others it occurs because the rise in native-born poverty is much greater than the rise in foreignborn poverty (e.g. Pre-emerging gateway, rural and small metropolitan areas in the midwest); and in the remainder of places it occurs because native-born rates increased while foreign-born poverty rates barely changed. 9 Foreign-born poverty rates are higher than native-born poverty rates everywhere in both time periods but these differences are very uneven. In traditional gateway metropolitan areas the gap between immigrant and native-born poverty at the start of the decade was below the national average, but considerably above this average in emerging gateway types (especially in Pre-emerging and Re-emerging gateway types). This difference perhaps reflects the presence in traditional gateways of diverse nativeborn populations many of whom are second-generation Asian and Latino immigrants. These people, who may contribute to elevated native-born poverty rates, are much less likely to be present in pre-emerging and re-emerging gateway types. THE GEOGRAPHY OF IMMIGRANT POVERTY – A DECOMPOSITION APPROACH What factors cause immigrant poverty rates to vary across gateway types – to be lower, for instance, in Continuous than in Post WWII gateways, or to be higher in Pre-emerging than in Emerging gateways (Table 4)? One possible reason is that immigrants do not have the same personal /household characteristics in each location. In some places, they might be less likely to have the skills necessary to get a decent job and more likely to be in household types (e.g., single parent) prone to economic marginality. Locations with greater concentrations of the foreign born with these characteristics would tend to have higher immigrant poverty rates than locations with smaller concentrations. Spatial variation in key personal/household characteristics, however, is unlikely to explain all of the spatial variation in immigrant poverty. Those with the same human capital and family structure may experience different risks of being poor depending on the local economic conditions they experience. Broadly speaking, the geography of poverty is attributable to both people and place effects and one way to measure their relative importance is to follow the decomposition procedure outlined in Odland and Ellis (1998). Comparisons of these two effects at different time periods – 2000 vs. 2007-9 – will reveal the changing relative importance of demographic characteristics and local economic circumstances (which we label “metro context”) in generating the geography of poverty. We decompose immigrant poverty rates (and for comparison purposes native-born poverty rates) as follows. Let fij be the proportion of a particular group (immigrants or the native born) in area j who are in category i (which indexes personal, family, and human capital characteristics), and qij is the poverty rate for these same households then the overall poverty rate pj for area j is equal to: pj = ifijqij (1) 10 This in turn can be re-written in deviation form as: ifijqij - ifiqi = iqi(fij-fi) + ifi(qij-qi) + i(qij-qi)(fij-fi) (2) where fi is the mean proportion in category i and qi is the mean poverty rate in category i—both calculated across the set of local areas. Thus ifiqi is the mean poverty rate over all j areas for the group in question. The first term on the right hand side, iqi(fij-fi), measures the effect of variation in the composition of local populations calculated at mean immigrant poverty rates for each category. We call this the “demographic structure effect.” The second term, ifi(qij-qi), measures the effect of deviations of local poverty rates from the mean poverty rate, calculated at mean proportions of the population in category i. We label this the “metro context effect.” The final term, i(qijqi)(fij-fi), is necessary to account for any interaction between poverty rates and the distribution of the group population over the i categories. The relative importance of the demographic and metro context effects in specific gateway types over time is of primary interest. We can extend the analysis to measure how much of the variance in pj is due to variations in metro context and demographic structure effects. The variance of pj is the sum of the variances of the three terms of equation (2) plus relevant covariances. Although it is possible for these covariances to be large we expect from previous research the most important terms to be the variances for the metro context effect and the demographic structure effect. The former will be the largest component of the variance when local conditions explain variations in immigrant poverty across the country; the latter will be the largest component when geographical variation in group characteristics explains the geography of group poverty. The magnitude of the covariation between the metro context and demographic structure effects is potentially interesting; it is a measure of how well we can separate these two influences. If this covariation is positive then subgroups that are disproportionately poor tend to cluster in locations that are unfavorable for escaping poverty and vice versa. The covariances involving the interaction effect – the final term in equation (2) - are likely to be very small. Householders 18 and over rather than persons are the demographic units in the decomposition. We switch the unit of analysis because some of the key determinants of poverty vary by household type (single, married, presence of children) rather than by individual; or they are most logically associated with an adult member of the household (e.g., education), typically the householder. The mixture of immigrants and native-born individuals in the same household, typically native-born children of immigrant parents further complicates analysis at the individual scale. For example, the native-born children of immigrants will likely experience risks of poverty based on their parent’s 11 characteristics. In our household scale analysis, such children are part of a household headed by a foreign-born householder. Figure 3 charts poverty rates by key socio-demographic characteristics used in the decomposition. Foreign-born householders are split into the same categories as the native born and have an additional US residency category – more than 10 years and less than or equal to 10 years in the country. Poverty rates vary in broadly similar ways for the native and foreign born. Married households with children have the lowest rates of poverty; unmarried households with children have the highest. Whites have the lowest poverty rates in both native- and foreign-born populations; but blacks experience the highest native-born poverty rate whereas Hispanics hold that position among the foreign born. More education reduces the chances of being poor. Those with a college degree have lower rates of poverty; those with skill deficits (measured by education) have the highest poverty rate. Note that equivalent levels of education translate into lower poverty rates for the native born at all grades. For immigrants, greater time in the country corresponds to substantially lower poverty rates. Subdividing the native- and foreign-born householder population by these characteristics and applying the decomposition technique in equation 2 yields the distribution of metro context and demographic effects by gateway type displayed in Figure 4 (native born) and Figure 5 (foreign born). For natives, metro context effects are generally negative – meaning favorable – in most one million plus population metropolitan areas (the top seven sets of twinned bars representing the major metropolitan gateway types). In contrast, these effects are positive (i.e., they increase the poverty rate) in smaller metropolitan and rural areas across the country, though they are especially pronounced in the rural south and west. Trends over time suggest local economies have become relatively more favorable (poverty reducing) in Continuous, Post-WWII and Emerging Gateways and in small metro and rural areas of the south and west. The opposite – a more positive (i.e. poverty increasing) metro context effect occurred in Pre-emerging and Re-emerging gateways and especially in the rural and small metropolitan areas of the midwest. The latter region was hit especially hard by the great recession so this latter finding is not surprising. Demographic structure effects do not correlate strongly with metro structure effects for the native born. The native-born population structures of Continuous and Re-emerging gateways and the rural northeast are favorable for reducing poverty; the rural and small town south native population has characteristics that tend to elevate poverty. Not much changed in these demographic structure effects in the 2000s. In Continuous gateways, however, demographic structure became less favorable. This perhaps signals the rising importance of second generation headed-households – a subpopulation of the native 12 born more likely to be poor than households headed by third or higher generation natives. The pattern of foreign-born metro context effects plotted in Figure 5 shows some broad similarities with these effects for the native born. For example, just as in the native-born case, metro context effects for the foreign born are strongly positive (i.e. poverty increasing) in rural and small metropolitan areas, and are largest in the south. Nevertheless, the foreign born exhibit some differences, most notably in Post-WWII gateways where in 2000 the local environment elevates the foreign-born poverty rate almost as much it does in the rural and small metropolitan south and west. In the same year, the three emerging gateway types had metro contexts favorable to poverty reduction among immigrants. Thus the dispersion of foreign-born populations from Post-WWII gateways to the largest new metropolitan destination types probably had a poverty reducing effect at the national level, at least in the period leading up to 2000. In 2007-9, however, the emerging gateway advantage declined; metro context effects in these places became less favorable for immigrants while those in Post-WWII gateways became less disadvantageous. The place disadvantage associated with the rural and small metropolitan area west also diminished over this period whereas it hardly changed in the south. Just as for the native born, place effects turned increasingly unfavorable for immigrants in the Midwest, especially so in small metropolitan areas. Thus if avoidance of the local conditions that elevate the odds of being poor was a motivating factor for shifts in immigrant geography away from Post-WWII gateways - and the western US in general - to new destinations (metropolitan or otherwise) in the 1990s, then the basis for that rationale appears to have weakened during the 2000s. Comparing the pattern of these metropolitan context effects with that for immigrant demographic structure effects – the left and right hand panels of Figure 5 respectively – reveals some interesting contrasts. Immigrants in Post-WWII gateways faced an unfavorable local environment and have characteristics that make them more prone to be poor. This contrasts with the situation in Emerging and Pre-emerging gateways; as already mentioned, these places have favorable metro contexts for avoiding poverty (although this advantage weakened in the 2000s) but have immigrants populations with characteristics more likely to make them poor. In other words, a large subset of new destination metropolitan areas are relatively good places to be as an immigrant – they are locales with labor market conditions that reduce the odds of being poor – but the immigrant populations there are disproportionately likely to be poor because of their demographic characteristics. This is probably because the immigrant population of new destinations are largely Hispanics, mostly from Mexico (Singer 2004, Massey and Cappoferro 2008). Elsewhere, with the exception of Former gateways, which have neutral metropolitan context effects but strongly favorable (i.e. poverty reducing) 13 immigrant demographic structure effects, there is a positive correlation between local conditions and population structure. That is, locations where immigrants possess characteristics likely to increase their chance of being poor are also places with local conditions that elevate the risk of poverty, and vice versa. A comparison between the geographic pattern of immigrant and native demographic structure effects reveals interesting similarities and differences by type of place. Demographic structure effects are large and positive in rural and small metropolitan areas of the south for immigrants and the native born, which means both groups in these places have characteristics that increase the odds of being poor. The opposite is true in Continuous gateways; there both native- and foreign-born populations have characteristics that alleviate the likelihood of being poor. Immigrant and native populations in the small metropolitan and rural areas of the Northeast both have favorable demographic characteristics; but these demographic structure effects appear to be markedly stronger for the foreign born, especially in rural areas of that region. But elsewhere, demographic structure effects for immigrants and natives diverges. For example, in Pre-emerging gateways, rural and small metropolitan areas of the west, and the rural midwest, immigrants have characteristics that increase their poverty rate whereas the opposite is true – albeit only slightly – for natives. In Former gateways immigrants have characteristics that reduce their poverty substantially but the native born have the opposite population structure – their characteristics increase their poverty rates in these places. Immigrant and native populations coincide in their greater or lesser risk for poverty in some locations but not in others. Locations where immigrants have unfavorable demographic characteristics but natives have the opposite are potentially sites where sensitivity to growing immigrant populations may be intensified by the tendency of local immigrant populations to be disproportionately poor. In the 2000s, the pattern of change in immigrant demographic structure effects signals improvement in characteristics that affect the risk of poverty in Continuous and PostWWII gateways and in the three emerging gateway types, although these improvements in emerging gateway types are much smaller. In contrast, the characteristics of immigrants in rural and small metropolitan areas in every region shifted to the right (i.e. became more likely to be poor). The results in Figure 5 suggests there may be an increasing positive association over time between people and place effects; places with conditions likely to elevate poverty are also places with immigrants who have characteristics likely to render them poor. A partition of the variance in poverty rates across the 57 locations (49 metropolitan areas with a million or more people and the eight rural and small metropolitan location categories) by the components on the right hand side of equation 2 (see Figure 6) 14 confirms this impression.6 Before we turn to a lengthier discussion of this covariation we offer some insights on the trends in the other major components of the variance decomposition. The first thing to note is that for both groups in both years variations in metropolitan context effects explains most of the geography of poverty. This means place effects account for more of the variance in poverty rates than does variation in the characteristics of local populations. Metropolitan context effects account for more of the variations in native-born than immigrant poverty in both 2000 and 2007-9 and these effects become markedly more important for the native born at decade’s end. The growing importance of place for native poverty during the 2000s accords with the notion that this group has been substantially harmed by the recession and that the geographic unevenness of the effects of the economic downturn is increasingly driving spatial variability in native-born poverty rates. The opposite appears to be true for the foreign born; difference in metropolitan context effects became a little less important source of the variance in immigrant poverty. The reasons for this divergence become clear on inspection of the trends in variance attributable to demographic structure and, especially, its covariation with metropolitan context. Demographic structure effects are more important sources of variation in native- than foreign-born poverty in both 2000 and 2007-9, and they rise in importance for both groups during the decade at roughly equal rates in both groups. This suggests that who lives where has become a more important predictor of the geography of poverty for both natives and immigrants. The most dramatic change, however, and the biggest divergent trend in source of variation between the native and foreign born, is the covariation between people and place effects. Recall that this effect measures the extent to which the geography of population subgroups has adjusted to the spatial distribution of local economic conditions. If it is positive it means places with buoyant labor markets that are poverty reducing are populated with people who have characteristics that lower their odds of becoming poor and vice versa. A negative covariation means that people with characteristics that elevate their chances of becoming poor have the good fortune, on average, to live in places where local conditions are poverty reducing, or that people with characteristics that reduce poverty tend to live in less prosperous places. The covariance terms for both groups in both years are positive, meaning that people with favorable (unfavorable) characteristics tend to cluster in favorable (unfavorable) 6 We only show the three main components of the variance decomposition on this figure. We do not show the remaining three components – all involving the interaction effect (the last term in equation (2) – because they are very small. 15 places. But the trends in this covariance term are markedly different. It declines – almost by 50% - for the native born over the time-period in question, suggesting that the positive correlation between people and place effects has considerably weakened for this group. One possible explanation for this is that the great recession has disproportionately affected parts of the country previously immune from economic trouble, places where the populations have previously had relatively few people at risk of being poor because of their demographic characteristics. Consequently, these locations will register a weakening or reversal of their favorable metropolitan context effects while still possessing favorable native-born population structure. Writ large, the net result will be a weaker relationship between people and place effects For the foreign born, the covariance term trends dramatically in the other direction, increasing by over 200% between 2000 and 2007-9, and it becomes the second largest component overall, surpassing the variance in demographic structure effects. This suggests that immigrants in demographic categories more likely to be poor are, by 2007-9, much more likely to live in places where local economic conditions are unfavorable for poverty reduction. Absent changes in economic opportunity in these locations or the relocation of immigrants from them, or both, this is a worrying trend for it implies a reduction in the probability that immigrants in these places will escape poverty in the future. Finally, we explore the effects of changing immigrant and native-born demographic characteristics and geography on the national poverty rate. This extends the logic and method of the simple counterfactual experiment discussed earlier to account not only for changes in the percentage foreign born in the country but also for the diffusion of immigrants to places where poverty rates differ from those in traditional gateways, and the changing characteristics of foreign- and native-born populations in the 2000s. This counterfactual uses household rather than person data for the same reasons as the decomposition technique – the need to subdivide the population into subcategories at risk for poverty is most effectively cued on characteristics of the householder. This renders alternative estimates of poverty rates than for individuals but the differences between native- and foreign-born rates and their trends over time are very similar. Table 5 reports the 2000 and 2007-9 national poverty rates calculated using householders rather than individuals. These rates are lower than for persons by about 1.2 percentage points but the magnitude of the increase over this period is almost identical to that registered with person data. The shaded cells report what the US poverty rate would have been under various conditions. The shaded cells in row three report the household version of the simple national counterfactual discussed previously. Under this condition – the same foreign-born percentage of the population in 2007-9 as 16 in 2000 – overall poverty would have increased by 1.06 percentage points compared to the actual increase of 1.16 points - a small difference. The next row allocates the foreign-born population to its 2000 geography in addition to rolling back the foreignborn percentage of the population to the same date. Without diffusion in the 2000s, and with no relative growth in the foreign-born population over this time, the increase in overall poverty would have been 1.04 points. In other words, immigrant settlement diffusion accounts for a very small fraction of the increase in overall poverty above and beyond that accounted for by the changing relative size of the foreign-born population. The final two rows account for changing immigrant and native born household characteristics. Essentially, whether we only roll back immigrant characteristics to what they were in 2000 (row five) or roll back both immigrant and native-born characteristics to their 2000 distributions (row six) – there is very little effect on national poverty rates. In both instances, the counterfactual increase would have been almost identical to the actual increase, just over one percentage point. Thus, changes in immigrant or nativeborn characteristics appear to explain very little of the observed trends. The bottom line is that trends in immigration in the 2000s appear to have had little effect on changes in the overall poverty rate. DISCUSSION Trends in immigrant poverty in the 2000s differ from those for natives. As native-born poverty rates increased during this decade, driving up overall poverty rates, immigrant poverty rates declined nationally and in many – but not all – sub-national locations too. Consequently, the immigrant share of the poor population dropped in many parts of the country, and the share held by natives increased. This happened despite growth in the size of the foreign-born population. New destination areas such as Emerging and Pre-emerging gateways and rural and small metropolitan areas in the south buck this trend. They have a rising fraction of immigrants in their poverty populations, partly because foreign-born poverty rates rose slightly in these locations and partly because foreign-born populations – which tend to be poorer than natives – grew faster than did native-born populations. Notably, traditional gateways, where most immigrants continue to live, experienced drops in foreign-born poverty, measured by both rate and poverty population share. Overall, despite the growth of the foreign-born population and settlement in new destinations, immigration trends account for a small fraction of the increase in overall poverty in the 2000s. Increases in native-born poverty rates, nationally and sub-nationally, drive growth in overall poverty. 17 In terms of the geography of these trends, we found that some new destination areas had lower immigrant poverty rates than some traditional gateways in 2000, a result that largely accords with previous findings (Crowley et al. 2006). Emerging gateways, for example, had lower immigrant poverty rates in 2000 than did Continuous and PostWWII gateways. And all three emerging gateway types had lower immigrant poverty rates than in Post-WWII gateways. We also confirmed that new destination rural and small metropolitan areas (e.g., in the south) have very high rates of immigrant poverty (i.e., above rates in traditional large metropolitan gateways). The 2000s reversed some of these differences. The poverty rate advantage for immigrants in the three emerging gateway types relative to the traditional gateway types narrowed or vanished depending on the locational comparison. The decomposition analysis reveals that in 2000, the three emerging gateway types were all places in which immigrants regardless of demographic characteristics were at lower risk for being poor than in traditional gateways. Thus immigrants were better off – at least in terms of the lower odds of being poor - in these new destination metropolitan areas than in old destinations. At that time, diffusion of immigrants to these new destinations made sense from an immigrant perspective even if the growing population of immigrants and their children in these places likely elevated overall poverty rates and increased demands on local human services. This place advantage, however, eroded partially or completely by 2007-9, depending on the emerging gateway type. This attenuation of favorable place effects, especially when it occurred in tandem with unfavorable demographic characteristics (e.g., in Preemerging gateways) is a recipe for increased immigrant poverty. More generally, the relation between people and place effects for immigrants strengthened over the 2000s. New destination locations that previously had favorable metropolitan contexts but immigrant populations prone to being poor lost their place advantage. This is worrisome because it suggests that immigrants will find it harder to leave the ranks of the poor in those locations. Our analysis tracked immigrant and native-born poverty rates from the start of the last decade into the depths of the great recession. The effects of that profound economic downturn will reverberate for years, perhaps even decades. Overall poverty tracks closely with unemployment (Isaacs 2011) and, unless we see significant employment growth, poverty rates will likely remain higher than they were a decade or so ago. A slow recovery will add pressure for immigration reform, which range from a new guest worker program or something far more comprehensive involving dismantling the 18 “family reunification” components of present policy perhaps toward a points system (after Canada) that favors immigrants with skills. With immigration reform currently gridlocked at the federal level, however, local governments are trying their own hand at legislation. And while local policy responses to immigration ranges from welcoming to hostile, places with high rates of foreign-born growth and places in the south are more likely to enact exclusionary policies (Walker and Leitner 2011). Many of these locales are what we have been calling “new immigrant destinations”. This local hostility varies from raw nativism to a concern that current immigration policy represents an unfunded local mandate. Many new destinations lack the resources to provide adequate schooling to the children of immigrant newcomers. Local services may already be strained by the recession and the addition of new student-age community members place an added burden on educational services. Schools in these places have suddenly found themselves needing more teachers and/or teachers and aides adept in language remediation the ability to hire additional personnel. A fear, of course, is that children already in or near poverty will grow up with skills and language disadvantages that reduce their chances of socio-economic success. The addition of a more general local intolerance of newcomers will only serve to further marginalize populations already struggling to provide for themselves and their children. REFERENCES Allard, S.W. and Danziger, S., 2000. Welfare Magnets: Myth or Reality? Journal of Politics, 62(2), pp.350-368. Borjas, G. J. 1990. Friends or strangers. New York: Basic Books. Borjas, G. J. 1999. Heaven’s Door. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. Boyd, M., 1989. Family and Personal Networks in International Migration: Recent Developments and New Agendas. International Migration Review, 23(3): 638-670. Clark, G.L., 1983. Interregional migration, national policy, and social justice, Rowman & Allanheld. Clark, G.L. and Ballard, K.P., 1980. Modeling out-migration from depressed regions: the significance of origin and destination characteristics. Environment and Planning A, 12(7): 799 – 812. 19 Cooke, T. and Marchant, S., 2006. The Changing Intrametropolitan Location of Highpoverty Neighbourhoods in the US, 1990-2000. Urban Studies, 43(11): 1971 -1989. Crowley, M., D. T. Lichter, and Qian, Z.. 2006. Beyond Gateway Cities: Economic Restructuring and Poverty Among Mexican Immigrant Families and Children. Family Relations 55 (3):345-360. Ellis, M. and Goodwin-White, J., 2006. 1.5 Generation Internal Migration in the US: Dispersion from States of Immigration? International Migration Review, 40(4): 899-926. Glasmeier, A., Martin, R., Tyler, P., and Dorling, D. 2008. Editorial: Poverty and place in the UK and the USA. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 1(1), pp.1 -16. Iceland, J. 2006. Poverty in America: A handbook 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press. Isaacs, J. B. 2011. Child Poverty during the Great Recession: Predicting State Child Poverty Rates for 2010. Institute for Research on Poverty Discussion Paper no. 1389-11. Jargowsky, P. A. 1997. Poverty and place: Ghettos, barrios, and the American city. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications. Jones, R. C. (Ed.) 2008. Immigrants Outside Megalopolis: Ethnic Transformation in the Heartland. Lexington Books. Kneebone, E., and A. Berube. 2008. Reversal of fortune: A new look at concentrated poverty in the 2000s. Brookings Institution. Kodras, J. E. 1997. The Changing Map of American Poverty in an Era of Economic Restructuring and Political Realignment. Economic Geography 73 (1):67-93. Lawson, V., L. Jarosz, and Bonds, A. 2010. Articulations of Place, Poverty, and Race: Dumping Grounds and Unseen Grounds in the Rural American Northwest. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 100 (3): 655-77. Li, W. 2009. Ethnoburb: the new ethnic community in urban America. University of Hawaii Press. 20 Lichter, D.T. and Crowley, M.L., 2002. Poverty in America: Beyond Welfare Reform, Population Bulletin 57, No 2. Washington DC: Population Reference Bureau. Light, I., 2006. Deflecting Immigration: Networks, Markets, and Regulation in Los Angeles, Russell Sage Foundation Publications. Massey, D. S. 2008. New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage Foundation Publications. Massey, D., S. and Capoferro, C., 2008. The geographic diversification of American immigration. In D. Massey S., ed. New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications, pp. 25–50. Odland, J., and Ellis, M.. 1998. Variations in the labour force experience of women across large metropolitan areas in the United States. Regional Studies 32 (4):333–347. Raphael, S., and Smolensky, E.. 2009. Immigration and Poverty in the United States. American Economic Review 99 (2):41-44. Singer, A., S. W. Hardwick, and C. Brettell eds. 2008.Twenty-first century gateways: Immigrant incorporation in suburban America. Brookings Institution Press. Sjaastad, L.A., 1962. The costs and returns of human migration. The Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), p.80–93. Waldinger, R. D., and Lichter, M. I.. 2003. How the other half works: Immigration and the social organization of labor. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Walker, K. and Leitner, H.. 2011. The variegated landscape of local immigration policies in the United States. Urban Geography 32 (2): 1-23. Zúñiga, V., and Hernández-León, R.. 2006. New destinations: Mexican immigration in the United States. Russell Sage Foundation Publications. 21 Gateway Type Metro Area Boston, MA-NH Continuous Chicago, IL New York-Northeastern NJ San Francisco-Oakland-Vallejo, CA Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood-Pompano Beach, FL Houston-Brazoria, TX Post WWII Los Angeles-Long Beach, CA Miami-Hialeah, FL Riverside-San Bernardino,CA San Diego, CA Atlanta, GA Dallas-Fort Worth, TX Emerging Las Vegas, NV Orlando, FL Washington, DC/MD/VA West Palm Beach-Boca Raton-Delray Beach, FL Austin, TX Charlotte-Gastonia-Rock Hill, NC-SC Pre-emerging Greensboro-Winston Salem-High Point, NC Raleigh-Durham, NC Salt Lake City-Ogden, UT Denver-Boulder, CO Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN Phoenix, AZ Re-emerging Portland, OR-WA Sacramento, CA San Jose, CA Seattle-Everett, WA Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL Total Pop 2000 3,951,557 8,804,453 18,372,239 4,645,830 1,624,272 4,413,414 12,368,516 2,327,072 3,253,263 2,807,873 3,987,990 5,043,876 1,375,174 1,652,742 4,733,359 1,133,519 1,167,216 1,499,677 1,252,554 1,182,869 1,331,833 2,412,400 2,856,295 3,070,331 1,789,019 1,632,863 1,688,089 2,332,682 2,386,781 % Foreign-born 14.64% 16.53% 26.33% 26.33% 25.22% 19.66% 34.86% 49.67% 18.73% 21.53% 10.45% 15.45% 18.01% 11.85% 17.41% 17.35% 12.76% 6.75% 5.52% 9.21% 8.53% 10.84% 7.22% 14.47% 11.25% 13.94% 34.09% 13.99% 9.83% Gateway Type Metro Area Baltimore, MD Buffalo-Niagara Falls, NY Cleveland, OH Former Detroit, MI Milwaukee, WI Philadelphia, PA/NJ Pittsburgh, PA St. Louis, MO-IL Cincinnati-Hamilton, OH/KY/IN Columbus, OH Indianapolis, IN Jacksonville, FL Kansas City, MO-KS Other >1m Nashville, TN New Orleans, LA Norfolk-VA Beach--Newport News, VA Oklahoma City, OK Providence-Fall River-Pawtucket, MA/RI Rochester, NY San Antonio, TX Total Pop 2000 2,513,661 1,175,089 2,255,480 4,430,477 1,499,015 5,082,137 2,500,497 2,602,448 1,473,012 1,443,293 1,603,021 1,101,766 1,682,053 1,234,004 1,381,841 1,553,838 1,157,773 1,025,944 1,030,303 1,551,396 % Foreign-born 5.82% 4.36% 5.04% 7.49% 5.21% 6.99% 2.50% 3.14% 2.75% 4.99% 3.22% 5.42% 4.88% 4.70% 4.72% 4.45% 5.38% 12.89% 5.89% 10.61% Continuous, Post-World War II, Emerging, and Re-Emerging gateways have foreign-born populations greater than 200,000 and either foreign-born shares higher than the 2000 national average (11.1 percent) or foreign-born growth rates higher than the national average (57.4 percent), or both. Former gateways are determined through historical trends (see below). Pre-Emerging gateways have smaller foreign-born populations but very high growth rates in the 1990s. The gateway definitions and selection are also based on the historical presence (in percentage terms) of the foreign-born in their central cities: Former: Above national average in percentage foreign-born 1900–1930, followed by percentages below the national average in every decade through 2000 Continuous: Above-average percentage foreign-born for every decade, 1900–2000 Post-World War II: Low percentage foreign-born until after 1950, followed by percentages higher than the national average for remainder of century Emerging: Very low percentage foreign-born until 1970, followed by a high proportions in the post-1980 period Re-Emerging: Similar pattern to continuous gateways: Foreign-born percentage exceeds national average 1900–1930, lags it after 1930, then increases rapidly after 1980 Pre-Emerging: Very low percentages of foreign-born for the entire 20th century Table 1. Gateway Classification after Singer (2004) 22 FB Population Share Metro > 1m NB Population Share 2000 2007 2008 2009 2000 2007 2008 2009 Continuous 25.7% 23.4% 23.6% 23.0% 10.6% 10.1% 10.2% 10.2% Post-WWII 25.6% 23.6% 23.3% 23.5% 7.5% 7.8% 7.8% 7.8% Emerging 8.5% 10.0% 10.3% 10.2% 6.1% 6.6% 6.7% 6.8% Pre-emerging 1.7% 2.1% 2.2% 2.3% 2.4% 2.6% 2.7% 2.7% Re-emerging 8.0% 8.8% 8.7% 8.5% 6.3% 6.6% 6.6% 6.7% Former 3.9% 4.0% 4.0% 4.1% 8.3% 7.9% 7.8% 7.8% Other Metro >1m 3.3% 3.6% 3.6% 3.8% 6.5% 6.5% 6.5% 6.6% 15.9% 16.8% 16.7% 16.9% 25.9% 26.1% 26.1% 26.1% Metro < 1m Non Metro TOTAL 7.4% 7.6% 7.6% 7.7% 26.3% 25.8% 25.7% 25.5% 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% 100.0% FB Population LQ Metro > 1m NB Population LQ 2000 2007 2008 2009 2000 2007 2008 2009 Continuous 2.09 1.98 1.99 1.95 0.86 0.86 0.86 0.86 Post-WWII 2.68 2.42 2.40 2.41 0.79 0.79 0.80 0.80 Emerging 1.34 1.41 1.44 1.42 0.96 0.94 0.94 0.94 Pre-emerging 0.76 0.83 0.85 0.86 1.03 1.02 1.02 1.02 Re-emerging 1.23 1.28 1.26 1.24 0.97 0.96 0.96 0.97 Former 0.50 0.54 0.54 0.56 1.06 1.07 1.07 1.06 Other Metro >1m 0.53 0.59 0.58 0.61 1.06 1.06 1.06 1.06 Metro < 1m 0.64 0.68 0.67 0.68 1.04 1.05 1.05 1.05 Non Metro 0.31 0.32 0.32 0.33 1.09 1.10 1.10 1.10 Table 2. Distribution of Native- and Foreign-born Populations by Gateway type 23 F Figure 1. Pove erty Rates by Gateway G Type 24 2000 % pop FB Metro > 1m West South Midwest Northeast % poor pop FB 2007/9 % poor pop FB / % pop FB % poor pop FB % poor pop FB / % pop FB Continuous Gateway 22.94% 29.04% 1.27 24.56% 28.13% 1.15 Post-WWII Gateway 30.12% 39.09% 1.30 30.53% 35.39% 1.16 Emerging Gateway 1.29 15.03% 22.91% 1.52 18.04% 23.21% Pre-emerging Gateway 8.55% 15.92% 1.86 10.73% 16.69% 1.56 Re-emerging Gateway 13.88% 25.14% 1.81 16.06% 23.31% 1.45 Former Gateway 5.64% 7.08% 1.26 6.99% 7.94% 1.14 Other Metro >1m 5.81% 8.63% 1.48 7.37% 9.97% 1.35 1.39 Metro < 1m 13.69% 22.48% 1.64 14.55% 20.27% Rural 6.66% 10.09% 1.51 7.13% 9.52% 1.34 Metro < 1m 5.93% 9.99% 1.69 7.41% 10.68% 1.44 Rural 2.95% 4.28% 1.45 3.74% 4.97% 1.33 Metro < 1m 3.88% 6.48% 1.67 4.76% 6.44% 1.35 Rural 1.93% 3.35% 1.74 2.25% 3.41% 1.51 Metro < 1m 6.67% 8.73% 1.31 8.29% 9.47% 1.14 Rural US 3.56% 3.95% 1.11 4.21% 4.26% 1.01 11.24% 16.09% 1.43 12.68% 15.24% 1.20 Table 3. Foreign-Born Share of Poor Population by Gateway Type 25 % pop FB 2000 Poverty Rates Metro > 1m West South Midwest Northeast 2007/9 Poverty Rates Native Born Foreign-Born Native Born Foreign-Born Continuous Gateway 10.79% 14.83% % diff 37.46% 10.99% 13.21% 20.23% Post-WWII Gateway 13.31% 19.82% 48.93% 13.13% 16.37% 24.65% Emerging Gateway 8.76% 14.71% 67.98% 10.66% 14.64% 37.31% Pre-emerging Gateway 8.92% 18.06% 102.33% 11.50% 19.17% 66.72% Re-emerging Gateway 8.26% 17.22% 108.37% 10.36% 16.46% 58.90% Former Gateway 10.57% 13.48% 27.54% 12.40% 14.23% 14.75% Other Metro >1m 11.21% 17.17% 53.07% 12.65% 17.58% 39.05% Metro < 1m 12.71% 23.23% 82.79% 13.80% 20.60% 49.28% Rural 13.95% 21.93% 57.18% 14.28% 19.60% 37.21% Metro < 1m 13.98% 24.63% 76.10% 15.76% 23.55% 49.39% Rural 17.07% 25.10% 47.07% 18.35% 24.68% 34.54% Metro < 1m 10.02% 17.20% 71.68% 13.56% 18.66% 37.60% Rural 10.54% 18.56% 76.09% 13.30% 20.37% 53.15% Metro < 1m 10.05% 13.46% 33.97% 11.42% 13.21% 15.72% 9.80% 10.91% 11.32% 10.86% 11.01% 1.36% 11.79% 17.85% 51.43% 13.26% 16.43% 23.85% Rural US Table 4. Native- and Foreign-born Poverty Rates by Gateway Type 26 % diff F Figure 2. Nativ ve- and Foreig gn-Born Percentage Change es in Poverty Rates by Gatew way Type 27 Native‐born Foreign‐born Married with Kids Married with Kids NonMarried with Kids NonMarried with Kids Other Other Asian/Other Asian/Other Hispanic Hispanic Black Black White White over 65 51 - 64 over 65 35 - 50 51 - 64 18 - 34 35 - 50 BA + 18 - 34 Some College HS or < BA + 2007-9 2000 2000 2007-9 Some College > 10 yrs HS or < <=10 yrs 0% 5% 10% 15% Poverty Rate 20% 25% 30% 0% 5% Figure 3. Variations in Poverty Rates by Householder Characteristics, 2000 and 2007-9 28 10% 15% Poverty Rate 20% 25% 30% Metro Context Effect Demographic Structure Effect Continuous Gateway Continuous Gateway Post-WWII Gateway Post-WWII Gateway Emerging Gateway Emerging Gateway Pre-emerging Gateway Pre-emerging Gateway Re-emerging Gateway Re-emerging Gateway Former Gateway Former Gateway Other Metro >1m Other Metro >1m Metro < 1m - West Metro < 1m - West Rural - West Rural - West Metro < 1m - South Metro < 1m - South Rural - South Rural - South Metro < 1m - Midwest Metro < 1m - Midwest Rural - Midwest Rural - Midwest Metro < 1m- Northeast Metro < 1m- Northeast 2000 2007-9 Rural - Northeast ‐6% ‐5% ‐4% ‐3% ‐2% ‐1% 0% 1% 2% 3% 4% 5% 2000 2007-9 Rural - Northeast 6% ‐6% ‐5% ‐4% ‐3% Figure 4. Components of Geographic Variation in Native-Born Poverty by Gateway Type 29 ‐2% ‐1% 0% 1% 2% 3% 4% Percentage Point Shift due to Demog Structure Effect Percentage Point Shift due to Metro Context Effect 5% 6% Demographic Structure Effect Metro Context Effect Continuous Gateway Continuous Gateway Post-WWII Gateway Post-WWII Gateway Emerging Gateway Emerging Gateway Pre-emerging Gateway Pre-emerging Gateway Re-emerging Gateway Re-emerging Gateway Former Gateway Former Gateway Other Metro >1m Other Metro >1m Metro < 1m - West Metro < 1m - West Rural - West Rural - West Metro < 1m - South Metro < 1m - South Rural - South Rural - South Metro < 1m - Midwest Metro < 1m - Midwest Rural - Midwest Rural - Midwest Metro < 1m- Northeast Metro < 1m- Northeast 2000 2000 2007-9 Rural - Northeast ‐6% ‐5% ‐4% ‐3% ‐2% ‐1% 0% 1% 2% 3% 4% 5% 2007-9 Rural - Northeast ‐6% 6% ‐5% ‐4% ‐3% Figure 5. Components of Geographic Variation in Foreign-Born Poverty by Gateway Type 30 ‐2% ‐1% 0% 1% 2% 3% 4% Percentage Point Shift due to Demog Structure Effect Percentage Point Shift due to Metro Context Effect 5% 6% 60% Var(Metro Context) Var(Demog Structure) Covar(Metro,Demog) Percentage of Variation 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% NB 2000 FB 2000 NB 2007-9 Figure 6. Sources of Variation in FB and NB Poverty, 2000 and 2007-9 31 FB 2007-9 National Poverty Rate Percentage point difference since 2000 2000 Actual 11.72% 2007‐9 Actual 12.88% 1.16% 2007‐9 (2000: FB%) 12.77% 1.06% 2007‐9 (2000: FB%, Geography) 12.75% 1.04% 2007‐9 (2000: FB%, Geography, FB Characteristics) 12.77% 1.05% 2007‐9 (2000: FB%, Geography, FB and NB Characteristics) 12.91% 1.19% Table 5. Counterfactual Change in Overall US Poverty Rate Under Various Conditions (based on households) 32

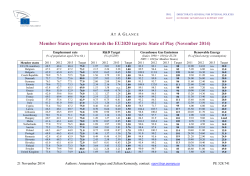

© Copyright 2026