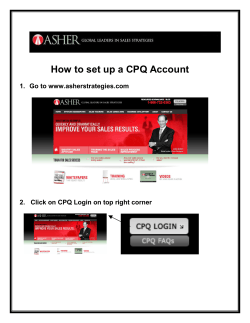

The report - Nordic Trial Alliance