SODIUM, POTASSIUM, AND HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE Learning Objectives

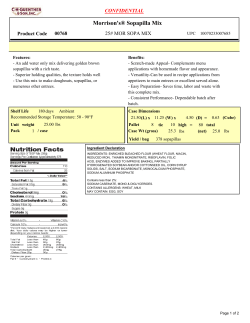

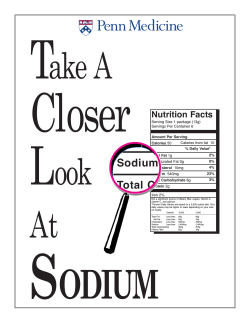

SODIUM, POTASSIUM, AND HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE by Thomas P. Martin, Ph.D., FACSM, RCEP and Anastasia N. Fischer, M.D. Learning Objectives • Highlight evidence documenting effect of high sodium intake on high blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular disease • Learn potential impact of reduction in sodium intake on health care costs • Appreciate the sodium-potassium connection and how potassium intake can blunt the effects of sodium on high blood pressure • Present strategies for reducing sodium and increasing potassium intake in the American population • Familiarization with dietary reference intakes Key words: Salt, Dietary Reference Intakes, Health Care Costs, Cardiovascular Disease, Nutrition INTRODUCTION T he purpose of this article is to review the importance of both sodium and potassium for normal body function as well as evidence that indicates excess sodium and inadequate potassium are both directly related to high blood pressure and the potential for subsequent cardiovascular disease. Recommendations/ strategies are presented to address the overconsumption of sodium and underconsumption of potassium in the American diet. (HBP) or hypertension is defined as a systolic reading greater than 140 mmHg or a diastolic reading greater than 90 mmHg (stage 1). Stage 2 and hypertensive crisis blood pressures also have been identified (Table 1) (1). Approximately 73 million Americans, or one in three adults, have HBP (17). Another 59 million have prehypertension (9). However, because HBP is an asymptomatic disease, the number is likely much higher. Adults older than 50 have a 90% lifetime risk of becoming hypertensive (32). Furthermore, it is estimated that 65% of those with diagnosed HBP do not have it under control (10). Consequently, there are millions of Americans at risk for serious health problems related to their HBP. The health consequences of HBP are significant and include damage to the heart and coronary arteries, stroke, kidney damage, vision loss, and erectile dysfunction. HBP is known as the Bsilent killer’’ because there are no warning signs or symptoms. People often do not realize they have it until they suffer from a related condition. Seventy-seven percent of first-time stroke victims, HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE The American Heart Association defines normal blood pressure as a systolic reading less than 120 mmHg and a diastolic reading less than 80 mmHg. Prehypertension is defined as a systolic reading of 120 to 139 mmHg or a diastolic reading of 80 to 90 mmHg. High blood pressure VOL. 16/ NO. 3 ACSM’s HEALTH & FITNESS JOURNALA 13 Sodium, Potassium, and High Blood Pressure TABLE 1: Blood Pressure Categories and Definitions Blood Pressure Category Normal Systolic mmHg (upper no.) Diastolic mmHg (lower no.) less than 120 and less than 80 Prehypertension 120 to 139 or 80 to 90 HBP (hypertension) Stage 1 140 to 159 or 90 to 99 HBP (hypertension) Stage 2 160 or higher or 100 or higher Hypertension crisis (emergency care needed) Higher than 180 or Higher than 110 American Heart Association (1). 69% of first-time heart attack victims, and 74% of firsttime congestive heart failure victims have blood pressure above 140/90 mmHg (2). HBP was responsible for approximately one in six adult deaths in the United States in 2005. It was the largest single risk factor for cardiovascular disease mortality, accounting for approximately 45% of all cardiovascular deaths (14). Based on data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the death rate from HBP increased by 25%, and the actual number of deaths rose by 56% from 1995 to 2005 (18). The direct and indirect costs of hypertension were estimated to be $73.4 billion in 2009 (15). When HBP is confirmed in a patient, the first approach usually is to prescribe dietary changes that will result in reduced sodium consumption. If after 3 to 6 months, the patient returns and blood pressure remains high, then a first-order control medication (e.g., diuretic) is typically prescribed. The standard diuretic acts to reduce fluid volume, and in the process, both sodium and potassium are excreted in the urine. The loss of potassium can result in hypokalemia (insufficient potassium) with resultant muscle weakness, irregular heart rhythm, confusion, and increased salt sensitivity. This is why the patient starting a diuretic medication is advised to increase potassium consumption or take a potassium supplement. Many factors are known to influence and affect blood pressure: genetics (family history), excessive alcohol consumption, sex, age, body composition, physical activity (exercise), medical conditions, stress, smoking, and diet. This article addresses one aspect of diet, the impact of sodium and potassium intake on blood pressure, and the risk of cardiovascular disease. minerals that have been identified as micronutrients essential for normal body function. They are called micronutrients because they are needed by the body in small amounts (mg to Hg). Sodium and potassium are two of these minerals; they are essential for water balance, transmission of nerve impulses, and contraction/relaxation of muscle. Four categories of DRIs serve as important references for micronutrient consumption. The first is the recommended dietary allowance (RDA). This is the amount of a micronutrient, determined by sex and age, which is necessary to prevent a deficiency. RDAs are established to cover 98.75% of the population. The second is adequate intake (AI), which is used when an RDA has not been determined. AIs are believed to cover the needs of all individuals in an age/gender group, but lack of data or uncertainty in the data prevent being able to specify an RDA. The third is tolerable upper intake level (UL), which represents the highest intake that is likely to pose no risk of adverse health effects. The fourth is estimated average requirement. This is the average daily nutrient intake level estimated to meet the requirements of half of the healthy individuals in an age/sex group. RDAs, AIs, and ULs are references that are meaningful for the consumer, whereas estimated average requirements are used primarily by nutrition scientists. This article will emphasize the UL for sodium and the AI for potassium. Based on the UL, a high sodium intake is defined as an intake greater 2,300 mg/day. Based on AI, a low potassium intake is defined as an intake less than 4,700 mg/day (Table 2). SODIUM Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005 recommended that sodium consumption be limited to 2,300 mg/day or less. Furthermore, it recommended that individuals with hypertension, blacks, and middle-aged and older adults consume no more than 1,500 mg/day. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010 (DG 2010) recommends that sodium intake be less than 1,500 mg/day (28). This decrease was based on the statistic that now nearly 70% of U.S. adults are hypertensive, black, and middleaged or older adults. It is stated that this group would benefit from reduced sodium consumption. The AI and UL for sodium are 1,500 and 2,300 mg/day, respectively. These are small amounts. To put it in perspective, just one teaspoon of table salt (sodium chloride, NaCl; 40% Na and 60% Cl) contains about 2,300 mg of sodium. TABLE 2: Adequate Intake and Tolerable Upper Intake Levels for Sodium and Potassium DIETARY REFERENCE INTAKES The Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences establish dietary reference intakes (DRIs) that are used as references/guidelines for micronutrient consumption in the United States (22). There are currently 13 vitamins and 22 14 ACSM’s HEALTH & FITNESS JOURNALA | www.acsm-healthfitness.org AI (mg/day) UL (mg/day) Sodium 1,500 2,300 Potassium 4,700 Not determined Dietary reference intakes, reference (21). VOL. 16/ NO. 3 Potential Consequences of High Sodium Intake It has been well documented that high sodium can trigger increased sodium retention, which can result in increased fluid volume and HBP. HBP is directly related to the risk of heart disease and stroke (30). Other potential negative effects of excess sodium consumption include the following: • increased calcium excretion (27,28) • kidney damage (12,28,33) • atherosclerosis/arteriosclerosis (11,12) • left ventricular hypertrophy (17,28) • increased incidence of gastric cancer (28) • increased risk of dementia (7) Negative Impact of Sodium Questioned A recent article titled BIt’s Time to End the War on Salt,’’ makes the argument that the recommendation to limit salt intact has little basis in science (20). The article related the results of select studies that found little or no relationship between salt intake, high blood pressure, risk of cardiovascular disease, and death. One study that the article’s authors highlighted to support their argument was a meta-analysis of seven studies that found no strong evidence between reducing salt and the risk of cardiovascular events (26). This study, and others presented to support the contention that there is little evidence to support a national effort to reduce sodium in the United States, was challenged in a recent professional commentary. Contrary to the original evaluation, He and MacGregor (13) reanalyzed the seven studies of the meta-analysis and found that they actually supported current health recommendations to reduce salt intake. The authors state that the substantial benefits in reducing the average intake of salt are supported by extensive evidence, including epidemiological studies, animal studies, randomized trials, and outcome studies. Furthermore, it should be recognized that the DG 2010 recommendation to reduce sodium intake is based on a far-reaching body of research that supports that recommendation. The population sodium reduction recommendation is supported by numerous professional organizations and associations, including the American Heart Association, the American Society of Hypertension, and the World Health Organization (28). classify individuals (authors’ emphasis) as salt sensitive or not (28, p. 334).’’ At the same time, it is meaningful to examine sodium sensitivity in these subgroups of the population. These subgroups, in combination, comprise the vast majority of the adult population in the United States. Therefore, the doseresponse relationship between sodium intake and blood pressure is important on the population level. Furthermore, the potential negative consequences of high sodium intake (beyond HBP) outlined above indicate that all individuals should be concerned with sodium consumption. Consumption of Sodium in the United States The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, which is part of the CDC. A recent analysis of the 2005Y2008 data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey divided the U.S. population into two groups based on the sodium recommendations of the DG 2010. Group 1 consisted of those who would benefit from reducing sodium intake to less than 1,500 mg/day, that is, persons age 51 years or older; blacks; and persons with hypertension, diabetes, or chronic kidney disease. Group 2 consisted of those who should limit sodium intake to less than 2,300 mg/day (everyone else). The average sodium consumption of group 1 was 3,264 mg/day, and that of group 2 was 3,513 mg/day. Furthermore, 98.6% of group 1 and 88.2% of group 2 exceeded guidelines (6). A Healthy People 2020 goal is to reduce average consumption of sodium to 2,300 mg/day by the year 2020 (30). Americans have found it difficult to reduce salt intake. This is primarily due to Baway-from-home’’ food intake and the consumption of processed foods. Away-from-home foods include meals and ready-to-eat items purchased at restaurants, preparedfood counters at grocery stores, and other outlets. The restaurant industry share of the food dollar has increased dramatically over the past 50 years and is currently at 49% of the total food budget (21). In general, fast food and restaurant food are high in sodium. Sodium Sensitivity Sodium sensitivity means that increased sodium loading will result in a rise in blood pressure and that decreased sodium intake will result in a reduction in blood pressure. Evidence from several studies has demonstrated a varied blood pressure response to sodium intake. For example, those with HBP, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease; those who are middle- and older-aged persons; and blacks tend to be more sodium sensitive than younger whites (28). However, BBecause no standardized diagnostic criteria and tests exist and blood pressure is highly variable, it is impossible to VOL. 16/ NO. 3 ACSM’s HEALTH & FITNESS JOURNALA 15 Sodium, Potassium, and High Blood Pressure Even patients with cardiovascular disease find it difficult to cut back on salt intake. In a study of 116 people with heart failure, researchers asked the subjects to write down everything they ate for 3 days. It was recommended that all patients eat a low-salt diet. The study found that participants consumed an average of 2,671 mg/day of sodium (AI is 1,500 mg, and UL is 2,300 mg), and only one third adhered to the recommended daily sodium intake. Most thought they were taking steps to reduce their sodium intake by putting less salt on their foods. What they did not realize is that most sodium comes from processed and restaurant foods (24). Why and How Sodium Is Consumed Salt is a common seasoning in most cultures. It tastes good, has its own flavor, and also enhances other flavors in food. Salt also is used as a food preservative, to enhance texture, mask bitterness, and is inexpensive. Therefore, it is not surprising that salt often is added during food processing. Major sources of sodium include bakery products (e.g., yeast breads), chicken and chicken mixed dishes, pizza, pasta and pasta dishes, processed meats (e.g., cold cuts, bacon, sausage, and franks), condiments (e.g., ketchup and salad dressing), Mexican mixed dishes, regular cheese, butter and margarine, grain-based desserts, soups, beef mixed dishes, canned food, foods with added external salt (e.g., potato chips and pretzels), pickles, and soy sauce (Table 3). Five percent of salt consumption comes from salt added during cooking, 6% is added at the table, 12% is occurring naturally in food, and 77% comes from salt that is added during food processing and at restaurants (19). It is clear that processed and restaurant food is high in sodium. Consumers need to recognize that fact and also learn to read labels to evaluate the salt content of food before purchase. disease by 60,000 to 120,000, stroke by 32,000 to 66,000, and myocardial infarction by 54,000 to 99,000 cases per year. It was projected that this sodium reduction would save $10 to $24 billion in health care costs annually. The researchers also stated that cutting just 1000 mg of salt daily would be more cost effective than using medication to lower blood pressure in all persons with hypertension (4). Recommendations/Strategies for Sodium Reduction in the United States According to the 2010 Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee report on strategies to reduce sodium intake, activities to reduce sodium intake have been going on in the United States for more than 40 years but have not succeeded (15). Consumer education, availability of select lower-sodium and reduced-sodium products, and voluntary reduction in sodium intake have not lowered overall sodium intake in the United States. Therefore, the report recommended strategies to further address excess sodium in the U.S. diet: Primary Strategy V The establishment of sodium Bsafe use’’ standards by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the food industry and restaurant/foodservice operators; these standards are to be implemented in a step-down fashion to promote decreasing consumer sensory preference for salt and industry adaptation. It was stated that BStandards for the addition of salt to processed and restaurant/food service foods are the best strategy to protect the public health (15, p. 9).’’ Interim Strategy V Food manufacturers and restaurant/ foodservice operators voluntary efforts to reduce sodium in processed foods and menu items, respectively. The CDC states that sodium consumption could be reduced by manufacturers gradually reducing the amount of sodium in their processed and prepared foods, with little or no behavior change on the part of the individual consumer (8). Sodium Consumption and Obesity One reason for the rise of sodium consumption is related to our national obesity epidemic. What a person eats is obviously important, but how much they eat also is a concern relative to sodium intake. Whatever the sodium content of a person’s diet, if they consume more food, they likely will be consuming more sodium. Therefore, some sodium reduction can reasonably be expected with the consumption of fewer total calories. Health-Care Costs According to two recent studies, a nationwide reduction in sodium intake would result in a significant decrease in health care costs. A 2009 study reported that reducing sodium intake by 1,110 mg/day could reduce hypertension cases by 11.1 million and result in a $17.8 billion (in 2005 dollars) savings in health care costs (23). Using predictive modeling, a 2010 study projected that a population-wide reduction of 1,200 mg/day of sodium could reduce the annual number of new cases of coronary heart 16 ACSM’s HEALTH & FITNESS JOURNALA | www.acsm-healthfitness.org Supporting Strategies • FDA and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to revise and update labeling based on a sodium AI of 1,500 mg/day and the expansion of these provisions and all labeling provisions to restaurant/foodservice operators, that is, improving point-of-purchase sodium information • leveraging, through government and nongovernment large food purchases; that is, setting salt specifications for food purchase. • promotion by government and nongovernment groups of the sodium intake goals established by the DG 2010. Also, providing support for consumers in making behavior changes to reduce sodium intake. • Continued and enhanced federal monitoring of sodium intake, salt taste preference, sodium content of foods, as well VOL. 16/ NO. 3 TABLE 3: Sodium Content of Selected Foods per Common Measure Description Common Measure Sodium (mg) 1 packet 3,132 Salt, table 1 tsp 2,325 Bread crumbs, dry, grated, seasoned 1 cup 2,111 Soup, onion, dry, mix Fast food, submarine sandwich, with cold cuts 1 - 6’’ roll 1,651 Wheat flour, white, all-purpose, self-rising, enriched 1 cup 1,588 Potato salad, home-prepared 1 cup 1,323 Fast food, cheeseburger; single, large patty; with condiments and bacon 1 sandwich 1,314 1 cup 1,284 Fast food, taco 1 large 1,233 Fast food, biscuit, with egg and sausage 1 biscuit 1,210 Beans, baked, canned, with franks 1 cup 1,114 Sauce, pasta, spaghetti/marinara, ready-to-serve 1 cup 1,025 Cheese, cottage, low fat, 1% milk fat 1 cup 918 Soy sauce made from soy and wheat (shoyu) 1 tbsp 902 Tomato products, canned, sauce Beef stew, canned entre´e Chicken pot pie, frozen entree, prepared Salami, cooked, beef and pork Snacks, pretzels, hard, plain, salted 1 cup 900 1 small pie 828 2 slices 822 10 pretzels 814 Macaroni and Cheese, canned entre´e 1 cup 761 Pasta with meatballs in tomato sauce, canned entree 1 cup 733 Fast food, pizza chain, 14’’ pizza, pepperoni topping regular crust 1 slice 670 Pickles, cucumber, dill or kosher dill 1 pickle 569 Bagels, egg 4’’ bagel 449 Waffles, plain, prepared from recipe 1 waffle 383 Pie, pumpkin, commercially prepared 1 piece 368 Fast food, Danish pastry, fruit 1 pastry 333 Cereals, Quaker, instant oatmeal, maple and brown sugar 1 packet 253 1 oz 248 Cheese, provolone Snacks, potato chips, barbecue-flavor Toaster pastries, brown-sugar cinnamon 1 oz 213 1 pastry 212 Catsup 1 tbsp 167 Salad dressing, Italian, reduced fat 1 tbsp 161 Candies, Reese’s peanut butter cups 1 package (2) 161 1 cup 150 Milk, chocolate, fluid, commercial, whole, with added vitamin A and vitamin D Sauce, barbecue 1 tbsp 133 Margarine-like, vegetable oil spread, 60% fat, stick with salt 1 tbsp 112 Butter, salted 1 tbsp 101 USDA National Nutrient Database, Nutrient Lists, Sodium; www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search. as population knowledge, attitudes, and behavior related to sodium. • Public-private partnerships to encourage consumers to take personal responsibility and action to reduce salt intake. The USDA has recently proposed new guidelines for school breakfasts and lunches subsidized by the federal government. VOL. 16/ NO. 3 These guidelines would require schools to cut sodium in meals by more than a half. They also would require that schools use only whole grains and serve low-fat milk. In addition, standards call for more whole fruits and vegetables and only one cup of starchy vegetables (29). The IOM has emphasized that the early stages of blood pressure-related atherosclerotic disease begin during childhood (28). ACSM’s HEALTH & FITNESS JOURNALA 17 Sodium, Potassium, and High Blood Pressure POTASSIUM Potassium is necessary for water balance, transmission of nerve impulses, maintenance of heart beat (rhythm), and muscle contraction. The AI for potassium is 4,700 mg/day, that is, more than three times the AI for sodium (1,500 mg/day). The CDC states that Americans should consume more potassium-rich foods to meet the recommended AI for potassium (7). Consumption of Potassium in the United States DG 2010 reports that the mean intake of potassium is approximately 3,200 mg/day for men and 2,400 mg/day for women (28). It was reported that less than 5% of Americans had potassium intakes above the AI during 1988Y1994 and that the number had decreased to 2.4% in 2003Y2004 (25). A moderate potassium deficiency is characterized by increased blood pressure, increased risk of kidney stones, increased urinary excretion of calcium, and salt sensitivity (16). Potassium blunts the effects of sodium and is therefore important in the control of blood pressure (3). A dietary practice to lower blood pressure is to consume a diet rich in potassium (25). Good Sources of Potassium Good sources of potassium include fruit, vegetables, legumes, juices, meat, fish, and dairy products (Table 4). A UL for potassium has not been established because it is virtually impossible to overdose on potassium from natural sources. However, it is possible to overdose on potassium by taking over-the-counter and/or prescription supplements. Older adults are at increased risk of potassium overload as a result of certain medical conditions, for example, diabetes, kidney disease, heart failure, and adrenal insufficiency. In addition, individuals taking medications, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and potassium-sparing diuretics, which can impair potassium excretion, should monitor their potassium consumption particularly from salt substitutes and supplements (28). Mortality File (1988Y2006), a nationally representative sample of 12,267 adults, to study all-cause, cardiovascular, and ischemic heart diseases mortality. The authors used mean sodium intake (mg/day) divided by mean potassium intake (mg/day) and found that a higher sodium-potassium ratio was associated with significantly increased risk of CVD and all-cause mortality. Furthermore, the findings did not differ significantly by sex, race/ ethnicity, body mass index, hypertension status, education levels, or physical activity. The combination of high sodium and low potassium showed a stronger risk for CVD and death than each mineral alone. The AI for sodium is 1,500 mg. The AI for potassium is 4,700 mg. Therefore, the AI sodium/potassium ratio is 1 mg of sodium to 3 mg of potassium (0.32). It seems that the importance of adequate potassium intake and its influence on blood pressure has been underappreciated. Furthermore, the sodiumpotassium ratio seems to hold promise as a valuable reference related to risk of disease. Suggestions for Potassium Increase in the United States It is suggested that Americans adjust their diets to include more natural sources of potassium. Diets with plenty of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy are recommended for heart health. One example is the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet (5). The DASH diet is rich in potassium and other minerals while encouraging people to eat less sodium-laden foods (28,31). It is recommended by the USDA as an eating plan for all Americans. The plan also emphasizes good eating habits, discourages processed foods, and suggests alternatives to Bjunk food.’’ The guide, which is available online (31), provides sample meal plans as well as the nutrition information on popular food items. The IOM Committee on Public Health Priorities to Reduce and Control Hypertension in the U.S. population has suggested Sodium/Potassium Ratio The intake of sodium and potassium and the function of these minerals in the body are related. For example, the sodiumpotassium pumps actively serve to maintain water balance between the intracellular and extracellular fluids. About two thirds of body water is intracellular, and one third is extracellular (e.g., blood plasma and interstitial fluid). Potassium is the main electrolyte in the intracellular fluid, and sodium is the main electrolyte in the extracellular fluid. Both a high sodium intake and a low potassium intake have been linked to HBP. Deductive reasoning supports the hypothesis that the sodium/potassium ratio also is linked to HBP. This theory is supported by a recent study that specifically examined the sodium/potassium ratio (34). This study utilized the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Linked 18 ACSM’s HEALTH & FITNESS JOURNALA | www.acsm-healthfitness.org VOL. 16/ NO. 3 TABLE 4: Potassium Content of Selected Foods per Common Measure Description Common Measure Potassium (mg) 1 cup 1,086 1 potato 1,081 Raisins, seedless Potato, baked, flesh and skin, without salt Soybeans, mature cooked, boiled, without salt Fish, halibut, Atlantic and Pacific, cooked, dry heat 1 cup 886 ½ fillet 840 Spinach, cooked, boiled, drained, without salt 1 cup 839 Beans, kidney, red, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, without salt 1 cup 713 Sweet potato, cooked, baked in skin, without salt 1 potato 694 Fish, salmon, sockeye, cooked, dry heat ½ fillet 632 8-oz container 579 Yogurt, plain, skim milk, 13 g protein per 8 oz Spinach, frozen, chopped or leaf, cooked boiled, drained, without salt 1 cup 574 Orange juice, raw 1 cup 496 Melons, cantaloupe, raw Bananas, raw Turkey, all classes, meat only, cooked, roasted Apricots, dried, sulfured, uncooked 1 cup 427 1 banana 422 1 cup 417 10 halves 407 Grapefruit juice, white, raw 1 cup 400 Peas, edible-podded, boiled, drained, without salt 1 cup 384 Corn, sweet, yellow, frozen, kernels cut off cob, boiled, drained, without salt 1 cup 382 2 slices 368 Milk, low fat, fluid, 1% milk fat, with added vitamin A and vitamin D 1 cup 366 Carrots, raw 1 cup 352 Ham, sliced, extra lean Beef, top sirloin, steak, lean only, trimmed to 1/8’’ fat, all grades, cooked, broiled 3 oz 320 Peppers, sweet, red, raw 1 cup 314 Grapes, red or green, raw Tomatoes, red, ripe, raw, year round average Broccoli, raw 1 cup 306 1 tomato 292 1 cup 278 Dates, Deglet Noor 5 dates 272 Strawberries, raw 1 cup 254 Onions, raw 1 cup 234 Chicken, broilers or fryers, breast, meat only, cooked, roasted ½ breast 220 1 oz (24 nuts) 200 Peanuts, all types, dry-roasted, without salt 1 oz 187 Watermelon, raw 1 cup 170 Wild rice, cooked 1 cup 166 Cucumber, peeled, raw 1 cup 162 Apples, raw, with skin 1 apple 148 1 cup 138 Nuts, almonds Lettuce, cos or romaine, raw USDA National Nutrient Database, Nutrient Lists, Potassium; www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search. a strategy of using Bmodified salt’’ in food preparation, in which part of the sodium chloride is replaced by potassium chloride. This would both increase potassium consumption and decrease sodium consumption. Those individuals for whom additional potassium is not advisable would be informed of the potassium content by appropriate labeling of products (14). VOL. 16/ NO. 3 The FDA requires that vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, and iron percent daily values (%DV) appear on the Nutrition Facts panel of labeled foods. This requirement is based on data that indicate that the average American diet is deficient in these micronutrients and that increased consumption could reduce the risk of related diseases. The American diet also is deficient in ACSM’s HEALTH & FITNESS JOURNALA 19 Sodium, Potassium, and High Blood Pressure potassium (25). There are at least three reasons why the FDA should require that a listing of potassium content in milligrams and %DV appear on the Nutrition Facts panel: it would alert consumers to the importance of potassium in a healthful diet; it would permit an easy comparison between sodium and potassium content; and increased potassium intake, along with decreased sodium intake, could result in a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease. As with sodium, efforts to achieve the AI for potassium across the U.S. population will require nutritional education, individual commitment, government support, and the cooperation of the food industry. We are just beginning to learn and understand the influence and interaction of single nutrients on each other and on body function. For example, vitamin D is important for the absorption of calcium, and vitamin C assists in the absorption of iron. Evidence suggests that sodium and potassium work together for water balance and, together, affect blood pressure as well as risk of disease. SUMMARY Dietary consumption of sodium and potassium has been implicated in control of blood pressure. Reducing the amount of processed and prepared foods in the diet will address excess sodium consumption, whereas increasing the consumption of foods high in potassium may help temper sodium excess and promote normotension. Evidence suggests that these changes would lower the prevalence of hypertension and the risk of cardiovascular and other comorbid diseases and result in reduced health care costs. References 1. American Heart Association Web site [Internet]. Understanding blood pressure readings. [cited 2011 November 20]. Available from: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HighBloodPressure/ AboutHighBloodPressure/Understanding-Blood-Pressure-Readings_ UCM_301764_Article.jsp. 2. American Heart Association Web site [Internet]. Why blood pressure matters. [cited 2011 November 20]. Available from: http://www.heart.org/ HEARTORG/Conditions/HighBloodPressure/WhyBloodPressureMatters/ Why-Blood-Pressure-Matters_UCM_002051_Article.jsp. 3. American Heart Association Web site [Internet]. Potassium and high blood pressure. [cited 2011 November 20]. Available from: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HighBloodPressure/ PreventionTreatmentofHighBloodPressure/Potassium-and-High-BloodPressure_UCM_303243_Article.jsp. 4. Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG, et al. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:590Y9. 5. Bray GA, Vollmer WM, Sacks FM, et al. DASH Collaborative Research Group. A further subgroup analysis of the effects of DASH diet and three dietary sodium levels on blood pressure: results of the DASH-Sodium Trial. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(2):222Y7. 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Usual sodium intakes 20 ACSM’s HEALTH & FITNESS JOURNALA | www.acsm-healthfitness.org compared with current dietary guidelines V United States, 2005Y2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(41):1413Y7. 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site [Internet]. Most Americans should consume less sodium. [cited 2011 November 20]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/salt/. 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site [Internet]. Sodium: the facts. [cited 2011 November 20]. Available from: http://www.cdc. gov/salt/pdfs/Sodium_Fact_Sheet.pdf. 9. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003; 289(19):2560Y72. 10. Chobanian AV. The hypertension paradox V more uncontrolled disease despite improved therapy. N Eng J Med. 2009;361:878Y87. 11. Dickinson KM, Keogh JB, Clifton PM. Effects of a low-salt diet on flow-mediated dilatation in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89: 485Y90. 12. He FJ, Marciniak M, Visagie E, et al. Effect of modest salt reduction on blood pressure, urinary albumin, and pulse wave velocity in White, Black, and Asian mild hypertensives. Hypertension. 2009; 54(3):482Y8. 13. He FJ, MacGregor GA. Salt reduction lowers cardiovascular risk: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9789):380Y2. 14. Institute of Medicine. A Population-Based Policy and Systems Change Approach to Prevent and Control Hypertension. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2010. 236 p. 15. Institute of Medicine. Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2010. 506 p. 16. Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2005. 640 p. 17. Liebson PR, Grandits G, Prineas R, et al. Echocardiographic correlates of left ventricular structure among 844 mildly hypertensive men and women in the Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study (TOMHS). Circulation. 1993;87:476Y86. 18. Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics V 2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):480Y6. 19. Mattes RD, Donnelly D. Relative contributions of dietary sodium sources. J Am Coll Nutr. 1991;10(4):383Y93. 20. Moyer MW. It’s time to end the war on salt. Scientific American, July 8, 2011 [cited 2011 November 20]. Available from: http://www. scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=its-time-to-end-the-war-on-salt. 21. National Restaurant Association Web site [Internet]. Facts at a glance: 2011 restaurant industry overview. [cited 2011 November 20]. Available from: http://www.restaurant.org/research/facts. 22. Otten JJ, Hellwig JP, Meyers LD, editors. Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2006. 560 p. 23. Palar K, Sturm R. Potential societal savings from reduced sodium consumption in the U.S. adult population. Am J Health Prom. 2009;24(1):49Y57. 24. Reilly CM, Frediani J, Clark P, et al. Heart failure patients may have trouble following low-sodium diets, paper presented at the American Heart Association’s 10th Scientific Forum on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research in Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke. Washington DC, April 25, 2009, abstract 235. 25. Sondik EJ. Focus area 19: nutrition and overweight progress review. National Center for Health Statistics, April 3, 2008. [cited 2011 VOL. 16/ NO. 3 November 20]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/healthy_ people/hp2010/focus_areas/fa19_nutrition2.htm. 26. Taylor RS, Ashton KE, Moxham T, Hooper L, Ebrahim S. Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (Cochrane Review). Am J Hypertens. 2011;24:843Y53. 27. Teucher B, Dainty JR, Spinks CA, et al. Sodium and bone health: impact of moderately high and low salt intakes on calcium metabolism in postmenopausal women. J Bone and Miner Res. 2008;23(9): 1477Y85. 28. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. Beltsville, MD: USDA; May 2010, p. 445. Available from: http://www. cnpp.usda.gov/DGAs2010-DGACReport.htm. 29. U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA unveils critical upgrades to nutritional standards for school meals. News Release No. 0010.11, January 13, 2010. Available from: http://www.usda.gov. 30. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Nutrition and Weight Status, NWS-19. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov. 31. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. DASH eating plan: Lower your blood pressure. NIH publication No. 06-4082; 1998, revised April 2006, p. 56. Available from: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/ public/heart/hbp/dash/new_dash.pdf. 32. Vasan RS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, et al. Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 2002;287(8):1003Y10. 33. Verhave JC, Hillege HL, Burgerhof JGM, et al. Sodium intake affects urinary albumin excretion especially in overweight subjects. J Intern Med. 2004;256:324Y30. 34. Yang Q, Liu T, Kuklina EV, et al. Sodium and potassium intake and mortality among US adults: prospective data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1183Y91. Thomas P. Martin, Ph.D., FACSM, RCEP, is a professor in the Health, Fitness, and Sport Department, Wittenberg University, Springfield, OH. He serves as an expert in the areas of energy metabolism/nutrition, body composition, and weight management in ACSM’s media referral program. Dr. Martin is ACSM Exercise Test TechnologistÒ certified and ACSM Registered Clinical Exercise PhysiologistÒ certified. His Web site is www.wittenberg.edu/~tmartin. Anastasia N. Fischer, M.D., is an assistant clinical professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Sports Medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine and Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, OH. She is a certified family practitioner and active member of the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Medical Society of Sports Medicine, and ACSM, where she is on the Board of Directors of the Midwest Regional Chapter. CONDENSED VERSION AND BOTTOM LINE High sodium and low potassium intakes are related to HBP and cardiovascular disease. Most Americans are overconsuming sodium and underconsuming potassium. Recommendations/ strategies are presented for the reduction of sodium consumption. It is suggested that increased potassium intake be encouraged along with sodium reduction to address the imbalance of these minerals in the typical American diet. Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest and do not have any financial disclosures. VOL. 16/ NO. 3 ACSM’s HEALTH & FITNESS JOURNALA 21

© Copyright 2026