Boyer & Cookston, 2015.pptx - San Francisco State University

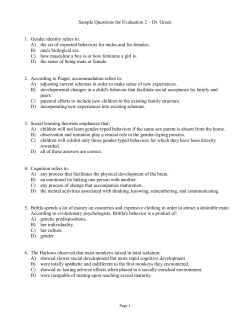

Change Over Time in Parent-‐Adolescent Conflict: Psychological Aggression as an Emerging Conflict Tac;c Chase J. Boyer San Francisco State University Abstract Research Question and hypotheses Does the trajectory of parent-child conflict across adolescence differ based on family structure, gender of child, and/or ethnicity? • H1: Conflict will increase more over time among stepfamilies than intact families. • H2: Adolescents will report more conflict over time with mothers than with fathers. Participants & Procedure • Participants were 392 adolescents and their parents who were in intact or stepfather families of Mexican-American (N = 193) and European-American (N = 199) ancestry drawn from the Parents and Youth Study (http://pays.sfsu.edu/). • Using a cohort sequential design, data were collected in four cohorts across three time points. Data were collected when adolescents were in 7th grade, 8th or 9th grade, and 10th grade. • During Time 1 and Time 3, data were collected using an in-person interview, however, a phone interview was employed at Time 2. Measures Intact-‐Families European-‐American Males 5.000 Intact-‐Families European-‐American Females 4.800 4.600 Es;mated Marginal Means Introduction • Parent-adolescent conflict rises in early adolescence, peaks in middle adolescence, and begins to decrease in late adolescence (Laursen, Coy, & Collins, 1998). However, it is unclear whether this pattern is shared by all adolescents. • Despite implications for adolescent maladjustment, psychological aggression (i.e., shouting, name calling) is a common conflict tactic employed by parents in the United States (Strauss, 2003). In a nationally representative sample of families, 88.6% reported using psychological aggression to resolve a parentchild conflict; shouting, yelling, or screaming emerged as the most common conflict tactic. • Conflict between adolescents and their mothers tends to higher in families with a stepfather present compared to families with co-resident biological parents (Schlomer, Ellis, & Garber, 2010). • Family conflict can occur across all family types and ethnicities, however, the meaning and form of conflict may depend on culturally-grounded family socialization practices (Yasui & Dishion, 2007). One study found that MexicanAmerican parents employed more harsh parental control but this behavior appeared to serve as a protective factor against acculturative stress. Figures Intact-‐Families Mexican-‐American Males 4.400 4.200 Intact-‐Families Mexican-‐American Females 4.000 3.800 3.600 Step-‐Families European-‐American Males 3.400 3.200 Step-‐Families European-‐American Females 3.000 2.800 Step-‐Families Mexican-‐American Males 2.600 2.400 2.200 2.000 1 2 3 Step-‐Families Mexican-‐American Females Wave Figure 1a. Adolescent’s reports of shouting, yelling, screaming, swearing, or cursing from their mother over time. Highlighted lines indicate a significant 4-way interaction for frequency of shouting by mothers F (2, 600) = 8.042, p = .016, ηp2 = .014. 3.200 3.000 Es;mated Marginal Means In the current study, we examined change over time in parent-adolescent conflict and explored differences by gender, family structure, and ethnicity. The 293 adolescents in the study reported the frequency of psychological aggressive conflict tactics from mothers and fathers/stepfathers across 3 waves from 7th-10th grade. Average adolescent conflict with mothers started higher and ended higher than conflict with fathers/stepfathers, but conflict with adolescents increased over time for both parents. Mexican-American females from stepfamilies reported the most increase over time in conflict with their mothers across both mother behaviors. While these descriptive results do not explain the processes driving destructive parent-adolescent conflict among families, family processes among racially/ethnically diverse stepfamilies merit further investigated. Jeffrey T. Cookston San Francisco State University 2.800 2.600 2.400 2.200 2.000 1.800 1.600 1.400 1 2 3 Intact-‐Families European-‐American Males Intact-‐Families European-‐American Females Intact-‐Families Mexican-‐American Males Intact-‐Families Mexican-‐American Females Step-‐Families European-‐American Males Step-‐Families European-‐American Females Step-‐Families Mexican-‐American Males Step-‐Families Mexican-‐American Females Wave Figure 1b.Adolescent’s reports of name-calling and threats their mothers across time. Highlighted lines indicate a significant 4-way interaction for frequency of shouting by mothers F (1.98, 593.87) = 7.440, p = .009, ηp2 = .016. Parent-Adolescent Conflict. Two items from the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale (CTSPC; Strauss et al., 1998) were used to assess the frequency of adolescent-reported psychological aggression employed by parents during conflicts with adolescents. Specifically, we measured two types of psychological aggression, shouting at the child or calling the child names. Items were, “In the past year, how often did shout at, yell at, scream at, swear at, or curse at your child?” and “In the past year, how often did you call (child) dumb or lazy or some other name like that, or say you would send him/her away or kick him/her out of the house?”. Both items were ranked on a scale of 1 (never in the past year) to 7 (more than 20 times in the past year). Measured as an effects model, the two items were intended to stand alone to indicate a frequency of behavior. The two items were constructed by collapsing the five items from the Psychological Aggression subscale of the CTSPC. Results & Discussion • Using repeated measures model ANOVAs, we measured each parentadolescent psychological aggression item individually across all 3 waves as the within-subject factor. We also measured family structure (i.e., step or intact), child gender, and ethnicity (i.e., European- or Mexican-American) as between-subject factors in each model. • Adolescent reports demonstrated a significant main effect for time on the frequency of shouting, yelling, screaming, swearing, or cursing directed at them by fathers/stepfathers F (2, 576) = 14.557, p < .001, ηp2 = .048, and mothers F (2, 600) = 29.103, p < .001, ηp2 = .088 such that this behavior increased linearly for mothers and fathers/stepfathers. Similarly, adolescents reported a main effect or time on the frequency of parentadolescent name-calling and threats both from mothers, F (1.98, 593.87) = 20.462, p < .001, ηp2 = .064, and fathers/stepfathers, F (2, 576) = 22.275, p < .001, ηp2 = .072. • Mexican-American females from stepfamilies emerged as experiencing the greatest increase in mother-adolescent conflict over time, whereas Mexican-American females from intact families experienced the least amount of change over time in mother-adolescent conflict (See Figures 1A and 1B). • Although our results do not explain the family processes that contribute to different levels of parent-adolescent conflict among stepfamilies and Mexican-American families, these results do suggest psychological aggression is a conflict tactic frequently used by European- and MexicanAmerican parents from both step- and intact families. • Future investigations would benefit from measuring changes in adolescent adjustment over time concurrently with changes in parentadolescent conflict. Acknowledgement We are grateful to the families who participated in these projects and also to the many members of the Parents and Youth Study for the data collection and entry of these data which made this work possible. To learn more about our lab visit http://bss.sfsu.edu/devpsych/fair/.

© Copyright 2026