essay - Palaver

palaver

/p ‘læv r/

e

e

n.

A talk, a discussion, a dialogue;

(spec. in early use) a conference

between African tribes-people and

traders or travellers.

v.

To praise over-highly, flatter; to cajole.

To persuade (a person) to do something; to talk (a person) out of or

into something; to win (a person)

over with palaver.

To hold a colloquy or conference; to

parley or converse with.

Masthead |

Spring 2015

Founding Editors

Sarah E. Bode

Ashley Elizabeth Hudson

Executive Editor

Patricia Turrisi

Editor-in-Chief

Ashley Elizabeth Hudson

© Palaver. Spring 2015 issue.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, without prior written permission from Palaver. Rights to

individual submissions remain the property of their authors.

Graduate Liberal Studies Program

University of North Carolina Wilmington

105 Bear Hall

Wilmington, NC 28403

www.uncw.edu/gls

Managing Editor

Erin Ball

Layout Editors

Ashley Elizabeth Hudson

Erin Ball

Copy Chiefs

Michael Arkinson

Liz Kachris-Jones

Jenna McCarthy

Kari Myrtle

Amanda Parkstone

Jarrett Piner

Staff

Mia Clifford

Mike Combs

Emily Fulbright

Alicia Jessup

Angela Keith

Eric Miller

Georgia Morgan

Gabe Reich

Layout Assistant

Gabe Reich

Contributing Editors

Dr. Josh Bell

Michelle Bliss

Sarah E. Bode

Dr. Theodore Burgh

Lauren B. Evans

Dr. Carole Fink

Courtney Johnson

Katja Huru

Rebecca Lee

Dr. Marlon Moore

Dr. Diana Pasulka

Dr. Alex Porco

Dr. Michelle Scatton-Tessier

Amy Schlag

Dr. Anthony Snider

Erin Sroka

Dr. Patricia Turrisi

Cover Art: “Recital” by Cade Carlson

Inside Sectional Art: “Home” by Cade Carlson

Thank you to the Graduate Liberal Studies Program at UNCW for letting us call you home, for the

resources and constant trust. Palaver staff, thank you for the many discussions and hours of careful

attention to edits. Palaver could not thrive without your dedication and enthusiasm. Sarah Bode, immense gratitude for your many hours of consulation during our transition. Erin Ball, newly inaugurated Managing Edtior, poet extraordinarre, Palaver thanks you for leaping into the fire and enduring the

job with grace and fervor. Thank you especially to our submitters, contributors, and readers for your

loyalty and for trusting us with your extraordinary work. Without you, we’d be an idea, an abstraction,

a what-if, but because of you we are Palaver.

Note From the Editor |

Ashley Elizabeth Hudson

T

his issue of Palaver marks our two-year anniversary. In childhood development terms,

this milestone would signal the apex of accumulated curiosity: a trial-and-error learning curve, a heightened quality of inquisitiveness and play, a ferocious questioning to

establish a sense of voice that continues to begat an ever-evolving sense of individuality and

place, and, most pointed-out in child-rearing communities, the tantrums that accompany a

growth-spurt in the marriage of mind and being. I’d say this is a pretty accurate way of thinking of Palaver’s push into our second year, and I’m excited to share this anniversary double-issue with our ever-growing loyal readership.

Palaver is a unique beast, publishing both creative and academic works that uphold our

mission of showcasing a consilience of interdisciplinarity, the merging of inspired minds on

fire through a diversity of mediums. Sometimes I can take that mission for granted, Palaver

being housed in the Graduate Liberal Studies program at UNCW, where the climate around

these parts is teeming with the electricity of seemingly-disparate connections, the white-hot

spark cast off from the passion of intellect’s need to tap its tendrils into an array of interests,

founded upon multiple disciplines. This issue of Palaver leapt together to do justice to our mission in ways that have surprised us all on the staff.

There’s this thing that happens sometimes, when submissions come to us, obviously, as

the solitary efforts of talented writers and artists, but, when considered alongside one another,

create a subtle narrative thread that feels down-right serendipitous, merging to create a larger

conversation. The pieces you will find in this issue of Palaver offer a quiet intensity that shines

a light upon personal perception and how that is impacted by familial circumstance, moving

into how the affixation of creativity to our inner narratives impacts our perceptions, and how

that, in turn, might begin to show us the problems and possibilities of creative expression.

We open this issue with Jean Burnet’s lyric essay “In Halves,” which explores the complicated nature of the stories we tell ourselves about our families, ethnicities, and creative

impulses, and the “between world” of identity as it traipses across generations. From there

we are confronted with Klaus Pinter’s art, which seemed to us a visual representation of the

tedium of exposing the self: the body becoming a paper doll, conformity crumpling into juxtaposition with the vulnerabilities of corporal flesh.

How appropriate, then, to transition to Kirby Wright’s poem where we listen in on the

speaker’s subtly startled assessment of the aging body: “I am a wrinkle/ Perched on stone.”

Christine Estima’s “Life Writing as Performance Art” and Becky Jo Gesteland’s “Divorce Education” push this theme into the realm of loves lost and gained, ushering us into a series of

pieces that highlight how poetry can pin down utterances that elevate us from self-and-other

reckoning. Then we’re back full circle to the pain and redemption of family circumstance with

Jonathan Lyons’ “Brothers” and Andrea A. Fitzpatrick’s “Sing Sing Dewys and Survival.”

Our love of interdisciplinarity surges with the pieces “Truth of the Tiger: A Jungian Exploration of Life of Pi,” “Three Doors to Survival: Invitation to a Garden Party,” “Thirteen,”

and “America(n),” where we are asked to confront what it means to be on a quest as a solitary

person, how purposeful interaction yields character, and, yet again, how family, trauma, and

our cultural assumptions shape us. Then, in a delightful synergy of familial and literary influence, we visit Jordan Scoggins’ essay and pictorial tour guide through an ancestral heritage of

the crayon portrait, instilling hope that what is discovered about one’s past might offer great

insight into one’s present.

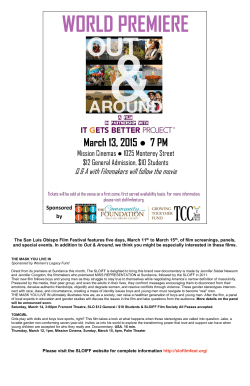

Finally, we end with a look at how the medium of cinema can bring about renewed hope,

beginning with Alison Morrow’s look at Scorsese’s film Hugo, which ushers us into a special section on Cucalorus Film Festival’s 20th anniversary. Palaver solicited writers to attend

the festival in Wilmington, NC, and we are thrilled to showcase their selections in this issue,

which include a profile on Cucalorus’ 2014 resident artists (one of which is Addison Adams,

whose entrancing art is featured throughout this issue), Dance-a-lorus (a film and dance collaboration), several films that explore the pitfalls and potentials of romantic love, and how one

filmmaker manages to keep his music video career from crashing into regretful failure through

a reconnection with his love of the genre.

Dear Reader, all of us here at Palaver thank you for your continued support of our journal

and for sharing with us the pleasure of synaptic discovery. I hope you delight in this very special issue of Palaver.

Table of Contents |

Spring 2015

In Halves 10

Jean Burnet

Untitled 25

Klaus Pinter

At WindanSea Beach, La Jolla 26

The Wounded Morning 39

Kirby Wright

Life Writing As Perfomance Art:

Narratives of Romance in Spoken

Word 27

Chirstine Estima

Making of My Dreams 33

The Beauty of Indecisions 34

Soul of a Mannequin 140

Dr. Ernest Williamson III

Divorce Education 35

Becky Jo Gesteland

Mary Surratt’s Umbrella 40

Bodily Resurrection 115

William Miller

Anne Carson and the Materiality of

Language 42

W.C. Bamberger

Head 88

Addison Adams

Cucalorus Film Festival 20th

Anniversary Special Section

La Pluralité Des Mondes 53

Kent David Weigle

Three Doors to Survival: Invitation to

a Garden Party 89

Dave Seter

Risky Business: Meet the Resident

Artists of Cucalorus 129

Lauren B. Evans

A Beauty Study 57

Veronica Watts

Thirteen 95

Tom Vollman

Brothers 58

Jonathan Lyons

America(n) 101

Winner of Palaver’s Flash Fiction

Contest

Mark L. Keats

Dance-a-lorus: A Marriage of

Mediums 133

Amanda Parkstone

Connection with a Higher Energy 51

Eclipse 52

Vitalii Panasiuk

Whoops 71

Dice (III) 117

Family Reunion 153

Temperance 159

Cade Carlson

Sing Sing Dewys and Survival 73

Andrea A. Fitzpatrick

A Heaven Full of Animals 79

What Happened to Heaven 80

Colin Dodds

The Truth of the Tiger: A Jungian

Exploration of Life of Pi 81

Ami Cox

Robert Paulson 103

The Unintentional Bullshit of Artistic

Expression: A Reflection on Robert

Paulson 104

Gregory J. Hankinson

Polishing the Gilt Easel: Iconography

of the Crayon Portrait 105

Jordan M. Scoggins

A Third-Told Tale:

What Dreams Are Made Of 118

Alison Morrow

The (Space) Age of Love 141

Sarah E. Bode

Glory Hallelujah 149

Chelsea Rose Rutledge

Someone’s Gotta Watch All These

Damn Music Videos 154

J. Gray

Despite Our Best Efforts 160

Ashley Elizabeth Hudson

In Halves |

Jean Burnet

I

am familiar with stories. My grandmother told the stories of our family. I remember now

only fragments, though they form some kind of puzzle in me. I remember how when she

tells a story it is while sitting at the kitchen table after falling into her seat. She is not a

woman that sits down; she plummets. She hurls, knees barely bending. She allows gravity to

pull at her body, heavy at the hips. My mother says, “Mamá, please. There are people living

on the floor below us.”

My grandmother doesn’t care. She waves her hand dismissively as if to say, don’t tell me

what I know. For many years, how she sits down is a point of contention between them. I

think now about how the way she heaves herself roots her to the ground, starting at her unbent knees and ending at her curled, dark toes. One day while she is sitting like this she says,

“Your hermanito was a good boy.” To her, he is especially good. “But too gentle—so little, and

blind.” An image of my brother as a younger version of himself comes to mind; he is small,

thin-shouldered, and knobby-kneed. Burnt caramel-colored in the sun, and wearing thick,

coke-bottle glasses. She says, “The boys on the street gave him trouble. But I put them in their

place.”

My brother is sitting near us when she tells me this, hunched over a plate of food. His

shoulders are difficult to read, some mixture between embarrassment and affection. He has always been very serious, but he almost smiles when he says, “She ran out of the house screaming once. Everyone saw her. Chased them with a broom. Called her la loca for a while.” I fill in

the rest of the scene: she must have been frying chicken on that day, and her hair was windswept and curly and large as she raced out of the kitchen to protect him. If it weren’t for her

knees, it’s a version of her now I can very easily believe.

She was that kind of woman; one who is not delicate—who does not sit gently, but demands that the world fix itself around her form.

Prod an Ecuadorian and she or he will tell you a story. And so I learned to value what

a story can hold. It was in the kitchen where our family stories were most often shared. My

grandmother frequently barred me from entering the space, afraid that I would get burnt with

hot oil or cut myself on some sharp, stray metal. Instead, I would listen to her sitting on the

border where carpet met linoleum. Stories became then a way of making.

I made up stories. I never spoke them out loud. The first time that I wanted to keep a story

must have been the first time I decided to put stories on paper. It must have been then that

writing became to me a way of holding. It must have been then that it became a way of learning if it is possible that, after everything, I am just some aberration in the pattern of our family,

or if it is possible that a family can evolve into something new.

Burnet | 10

malos sueños and mixed ink

The fact that I

am writing to you

in English

already falsifies what I

wanted to tell you.

My subject:

how to explain to you that I

don’t belong to English

though I belong nowhere else

—Gustavo Perez Firmat, “Bilingual Blues”

***

I am either white or brown. My father is Caucasian—a norteamericano—my mother is Ecuadorian. I can’t be both. I didn’t realize this until I met Alma Morales in the third grade. I remember how Alma taught me my first curse words (puta, mierda) at St. Elizabeth’s, where we

wore crisp but cheaply made uniforms, passing notes between class and before church, even

while being instructed on how to contact God. (“Shut your eyes tight when you pray, darlings,

it’s like picking up a telephone. If you peek, it’s as if you’re hanging up on God. You wouldn’t

want that, would you?”) There, on the blacktop, the student body spoke the language of our

families, our many different Spanishes.

It’s true that Alma Morales taught me all about words. One day she taught me something

new about what words can do when she called me the dirtiest one she knew: “Gringa.” White

girl. I chased after her, holding up the thin middle finger she had taught me how to make, for

some time following those shrill laughs singing gringa, gringa, gringa. Sometimes I think of this

moment in which a word was uttered in my direction that did not feel mine, and what it was

like to feel a lifetime’s worth of hate at her insinuation—that I was one of those white girls

with their ballet lessons, beach vacations, and ever present Daddies.

Rocio G. Davis calls this kind of living a “between-world,”1 an area between two places

and, by extension, two selves. Davis uses this term to refer to the immigrant experience, but

I say a mixed person is often an immigrant to their own people. My background and birthplace are at odds, and I’ve been in an acute position of observation. Both inside and outside this between-world, I

“…but I say a mixed

sometimes think of myself in quadruple: the me of home,

person is often an imwhich does not feel wholly Anglo or Ecuadorian; the me

that belongs to the culture inside of which I grow; the me

migrant to their own

that is informed by the culture that I do not know intipeople.”

mately; and the me that I make myself, that occurs somewhere in-between. This has been a constant struggle for

Davis, Rocio. “Identity in Community in Ethnic Short Story Cycles: Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club, Louise

Erdrich’s Love Medicine, Gloria Naylor’s The Women of Brewster Place.” Ethnicity and the American Short Story. Ed.

Julie Brown. New York: Garland, 1997. 3-24. Print.

1

Burnet | 11

me to articulate not only as an individual, but as a writer who experiences life in a language

that is not the language of my family.

When asked if he was trying to alienate non-Spanish speakers from reading his bilingual

book, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, author Junot Diaz said:

…people have come to me and asked me…are you to lock out your non-Dominican reader,

you know? And I’m like, no? I assume any gaps in a story and words people don’t understand, whether it’s the nerdish stuff, whether it’s the Elvish, whether it’s the character

going on about Dungeons and Dragons, whether it’s the Dominican Spanish, whether

it’s the sort of high level graduate language, I assume if people don’t get it that this is not

an attempt for the writer to be aggressive. This is an attempt for the writer to encourage

the reader to build community, to go out and ask somebody else. For me, words that you

can’t understand in a book aren’t there to torture or remind people that they don’t know.

I always felt they were to remind people that part of the experience of reading has always

been collective. You learn to read with someone else. Yeah you may currently practice it

in a solitary fashion, but reading is a collective enterprise. And what the unintelligible in

a book does is to remind you how our whole lives we’ve always needed someone else to

help us with reading.2

In this way, he offers a solution to a writer who is versed in two languages, but, more often, I

feel as if I am a master of none.

In an interview discussing his bilingual poems, Cuban-American author Gustavo Perez

Firmet puts it another way:

I don’t have one true language. I have a hard time saying “I love you” in Spanish. When I

say te quiero, te amo—it sounds stilted, sounds like the kind of speech you hear in Mexican

soap operas. But for me it’s very natural to say, “I love you” in English. My wife is American; English is a conjugal tongue, it’s a filial tongue. Every time I talk to my son or my

daughter, we end the discussion by saying, “I love you.”3

When I am blocked or in a state of confusion, when I

cannot find the words, these feelings are always part of a

larger creative process embedded in cultural mixing. To

live in a state of cultural ambiguity compels me to write,

but also asks me to call into question my legitimacy as a

voice to the cultures to which I belong.

“[Diaz] offers a solution

to a writer who is versed

in two languages, but,

more often, I feel as if I

am a master of none.”

Writing produces a kind of anxiety in me. To be a

writer is a lot like being a mixed person born to an immigrant family: nothing defined, everything loose and

boundless, sitting around waiting for something important to happen. Living in that state of

psychic unrest, to be in a state of in-between, is what produces art in any writer, mixed or not.

Diaz, Junot. Junot Diaz in conversation at the Sydney Writers’ Festival. The Book Show. Australian Broadcasting, 27

May 2008. Web. 15 January 2010.

3

“For A Bilingual Writer, ‘No One True Language.’”2 Languages, Many Voices: Latinos in the U.S. Natl. Public

Radio, 17 Oct. 2011. Radio.

2

Burnet | 12

Cultural ambiguity propels me to write. To live inside of oppositions creates some kind of

productive tension in me.

The longer the night lasts, the more our dreams will be.

el camino of the woman

—Chinese Proverb

La mujer del desierto, como el viento

sopla, hace dunas, lomas.

My family has an old tradition. I don’t know if they created it or if it comes out of our culture—often, I can’t tell the two apart. They say that to speak your bad dreams aloud to someone else is to ensure that they don’t come true. I sometimes feel as if writing is a way of speaking aloud the worst things and making them better. Or, sometimes, that it is its inverse—that

in speaking aloud a good thing, it will concretize its truth. And so I write.

When I write I feel as if I am recounting a dream to my mother, words that are shared in

the morning after or at night before I lie down for the next one. It is shared in a kind of intimacy that cannot be replicated by any other of our interactions. To share a dream is to make a

kind of confession. It is to share a truth about yourself that you have no control over. To share

a dream is to be cut open on the surgeon’s table, to let your insides spill from the metal surface

to the floor. It is an act of faith.

***

I’ve been reading about the Yoruba people, a West African group that believes that a name

will define one’s destiny. For families that have suffered the loss of many children, they often

use names that will ward death away, like Kokumo, this one will not die. I sometimes think

about whether the destiny my name’s given me is even mine.

My name is Jean Michelle Burnet, which doesn’t at all accurately indicate that my mother’s

name is Luz Pilar or that my grandmother’s is Blanca Alfonsina or that my brother’s name is

Ivan Cristobal. Jean is my father’s mother’s name, Michelle is the name my mother gave me

because it “sounded good with Jean,” and Burnet is my father’s name, but also the most convenient one to have to minimize discrimination (at least this is my mother’s explanation for

keeping his name—she is political in the most basic way).

I know very little about my grandmother Jean. My father sent me an old home video of

her once and I do recognize my hair in hers, frizzy and curly and big. I try very hard to form

some kind of connection with the woman that shares my name; because to share in a genetic

code makes the urge to link up primal, irrational. But when I think of “Jean” I think of knitting

scarves and grandchildren, which are two things I’m not good at making.

Still, having never met her or anyone else who knew her I’m left with a name that isn’t

particularly mine, that reminds me of its mis-possession all the time, like when my family

can’t—and how they could never really—pronounce it, our home often littered with: Meechtell. Yeanie Meechtell.

A secret: Burnet is pronounce burn it, but I’ve always told people it’s burn-eht, which is

Burnet | 13

in many ways in keeping with our family philosophy: put emphasis on the right parts, try to

make it sound just a little bit better.

—Gloria Anzaldua, “Mujer Cacto”

***

My brother and I are sixteen years apart. He is my half-brother, which adds to my life

another half of something I have to work to understand. In him, I see many of the things our

culture exults in men: aggression, force, authority. He reacts first and thinks later. There is a

kind of privilege in being a man, even in our family. Growing up, I see it only as natural that

he gets fed first and I second, that there is always the most rice on his plate. But in him I also

see many of the things our culture refuses to address: to be left behind, to be shoved off by

a man into the hands of a woman. Though we are sixteen years apart, we endure the same

loss—we endure the absence of a father. It bridges some of our halves. But his shame haunts

him—un espiritu de pena. Shame is like a poison, and to be shamed by a man, most especially

if you are a man, is the worst kind.

Men create the rules of our culture, women transmit them. As a

girl, my mother’s chief rule for me is

simple: don’t be a cajellera (a gossip,

a girl who is out too much). That she

invokes the rules that were once used

against her has always perplexed

me. In Ecuador she was a divorcee,

a characteristic that to her neighborhood might as well have put her on

par with prostitutes. In our culture,

women have three options: become a

nun, become a prostitute, or become

a mother. Though more progressive

venues of thoughts have shifted our

trajectory in millimeters—a woman

can be both educated and a mother,

for instance—these notions persist. It

invokes in women a kind of powerlessness.

I’m in my mother’s cousin’s home

in La Pradera, the old neighborhood

“Oblangle Fizz” by Addison Adams

Burnet | 14

in Ecuador, with the rest of the women from the street when they start to talk about their husbands. Her cousin says, “Si, he’s gone behind my back.” In our culture, a man that sleeps with

a woman other than his wife is to be expected. When her son walks into the room, she takes

him into her arms and says, “You would never hurt me like that, would you mijo?” He says,

“No, mami,” promising something he doesn’t even understand yet and I think, how do they

endure like this?

As a male Dominican author, Junot Diaz chiefly writes about the concerns of the young,

male Dominican. Though what it means to be a man, or what form authority can take, is prominent in his work, his depictions of women reveal almost as much about masculinity as his

depictions of men. When I read his work I sometimes feel as if I’m peeking behind the curtain,

into that place that women are barred from, the world of men.

In his story “Fiesta, 1980,” Diaz chronicles his protagonist Yunior’s inability to travel in

a vehicle for an extended period of time without vomiting, an act which ultimately appears

to be linked with his father’s affair with a Puerto Rican woman. But when Yunior’s attention

turns to his mother, there is a brief moment of revelation:

The only photograph our family had of Mami as a young woman, before she married Papi,

was the one that somebody took of her at an election party that I found one day while rummaging for money to go to the arcade. Mami had it tucked into her immigration papers. In

the photo, she’s surrounded by laughing cousins I will never meet, who are all shiny from

dancing, whose clothes are rumpled and loose. You can tell it’s night and hot and that the

mosquitos have been biting. She sits straight and even in a crowd she stands out, smiling

quietly like maybe she’s the one everybody’s celebrating. You can’t see her hands but I

imagined they’re knotting a straw or a bit of thread. This was the woman my father met a

year later on the Malecon, the woman Mami thought she’d always be. 4

To be a woman in our culture is to be in this state of before-and-after—that’s the problem.

For us there is only before becoming a mother, and then there is everything after. There is

this photo of my own mother standing in El Panecillo in Quito. She is wearing her hair long

around her shoulders, pants flared. She might be eighteen here, before my brother and I were

even a thought inside someone’s head. Here I see a culture’s mixed messages. Our mothers

teach us, don’t let any desgraciado treat you badly—and in the next breath they say, a good wife

needs to listen to what her husband tells her. These lessons emerge from the belief that the

individual is not as important as their role in the community—not more important than the

role they play for la familia. Selfishness is condemned, especially in women. And nobody ever

leaves, nobody ever moves out. Wives bring their husbands home, or husbands bring their

wives. Children get born and grandmothers become nannies. La familia is till death do us part.

For things to have value in man’s world, they are given the role of commodities.

Among man’s oldest and most constant commodity is woman.

—Ana Castillo, Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma

4

To be a part of two cultures gives me distance; it reveals to me contradictions, and puts

me immediately at odds. In letting me name them, being a writer often opposes what composes half my world. It gives a feminine voice to an act that is characteristically masculine—to

choose words, to create an individual truth, to have some autonomy. Even as I write this, I feel

some guilt for revealing myself.

My grandmother once told me the story of her first child. She was sixteen when she was

raped—though she would never use that word—by an older man, a family friend. She tells

me this one day sitting on her bed while a Catholic mass broadcasts at low volume in the

background. She does not tell me with embarrassment or shame, she tells in the way of fact.

She says, “I remember that it hurt very much.” My mother is nowhere near us, but I think now

that maybe this is not a story that she wants me to hear. “You must love a man very much to

let him touch you,” she continues. “You must want to be touched.”

She named the child Benigno, which means kind, or well-born. The one and only time I

meet him is on American soil, and he is as kind and generous as she depicts him in her stories. Some months later, when she’s weeping over his passing—a sudden, unexpected heart

attack—I still don’t know his story, but I feel the pain of his loss. It’s only many years later

that she tells me of his origin, one story she means to serve as a warning to be careful, that as a

woman I should not give myself too freely. I think now that she named him Benigno to erase

the shame of the act that had made him. She knew how to use words, too.

The shame that women endure is not a Latin-exclusive experience, but to talk about it out

loud is an Anglo one. The stories that were given to me were given to me by women exclusively, and so I have learned the rules that formed their experience through them alone. In telling

a story you can maintain a sense of personal history, but in writing it down, you give it shape.

To write it is to make it a kind of truth.

to heal, to be healed

The word

was born in blood,

grew in the dark body, beating,

and flew through the lips and the mouth.

—Pablo Neruda, “The Word”

***

I’m with my family at the Otavalo market outside of Quito, Ecuador, when a young woman dressed in traditional Andean clothing approaches me with both hands draped in strings of

red coral necklaces. Around us the market unwinds mazelike, colorful tapestries hung up on

stands, glazed ceramics getting hot in the sun. With her best salesman smile she presents her

hand to me, saying, “Buena suerte?” For good luck?

Diaz, Junot. Drown. New York: Riverhead, 1996. Print.

Burnet | 15

Burnet | 16

My mother starts rifling through the necklaces. Nodding every so often, she turns to me

and says, “You see? For good luck. Against curses.” I repeat to myself: my family isn’t crazy.

It’s in some ways unexpected that this strange string of events I’ve come to associate with

home has followed me thousands of miles away from there and into the Andes. But in other

ways it feels normal, like in the way I see my mother interact with the girl, easily, with some

familiarity, as if the exchange is happening in their living room. My mother convinces me to

buy one, which she clasps around my neck as if the gesture alone has permanently protected

me from harm.

Superstition has been perhaps my family’s greatest ongoing story, told and retold. My

grandmother taught me everything I know about superstition, and by extension, how to battle

every evil. When I was sick or moody, she never thought I was sick—she thought I was asustada. I’ve been scared, likely by something evil. She believed that I could be affected by evil

spirits from people, mostly strangers, unintentionally passing on jealous thoughts through a

striking glance. It was her reason why I wasn’t hungry or my nose was runny, or why I’d hole

up in my room. (If I leave rice on my plate, it’s a sign. If I’m uncommunicative, it’s a sign. If I

blink too often, or not enough, it’s a sign.) Adolescence is never as difficult as is it in a superstitious household. You never throw fits, you never get sick—instead, you’re always asustada.

On the days she feels I’m not myself, she waits until I’m not looking, tricking me into going

through a doorway first so that my back is vulnerable to her. She throws a glass of water at me,

exclaiming victory. Now, all bad intentions have been startled out of me. In her mind, I’ll get

better. I always think it’s simpler than that: I have a cold or I’m grumpy or maybe all I needed

was a nap, and now, my clothes are wet too.

I sometimes have trouble reconciling these two spiritualties, the Catholic and the pagan.

In Latin America, they are intertwined. Religion, shamanism, and home remedies are important resources in our culture. In Ecuador, both traditional and alternative medicines were

recognized in the constitutional reform of 1988, and Amazonian Quicha shamans and coastal

Tscháchila healers are still considered to be the most powerful healers and ministers by those

who come from many classes and backgrounds from the Sierra and the Coast.

The good stories are what no one wants to talk about.

So you make up a story because no one is going to tell you the truth.

—Sandra Cisneros

The first time I read Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street was the first time I read

about healing in the way my family had taught me. Esperanza, the young girl who acts as the

novel’s voice, occupies a between-world, too. Ethnically, she is a Mexican; culturally, a Mexican American. The street on which she lives depicts the experience of a diverse community

that is mainly, although not exclusively, Hispanic. Her observations are strung together, more

impressions than fully realized stories.

they are powerless. But besides the victimized, the other important female figures spotlighted

are the curanderas, or witch-women.

In my experience, curanderas feel like a link, a kind of pillar on which belief, on which

faith, can be sometimes balanced. Even when my family’s faith gets worn out, they still trust

in the power of a curandera. It is difficult to explain what it’s like to be embraced in the hands

of a curandera, but there is something powerful in having someone tangible, fleshy and real,

spiritualize your angers and hurts and shames. It evokes a feeling so particular that it almost

can’t be named.

In Chicano and Latino literature the curandera is a traditional figure that’s emerged as a

powerful female symbol. Myrna-Yamil González has this to say about the curandera:

The curandera has two attributes: a positive one as a healer and a negative one as a bruja

or witch/seer. The curandera possesses intuitive and cognitive skills; her connection to

and interrelation with the natural world is part of her ancient knowledge….[Her role] as a

powerful figure in the writing of both women and men demonstrates not only her enduring representational qualities as myth and symbol but also the close identification of the

culture with her mystic and spiritual qualities.5

Curanderismo’s practices are steeped in holiness and sacred prayer, in hands-on healing touch,

and platicas, talking as a spiritual companion. The history of curanderismo derives from ancient

methods descending from Native American, European, Eastern, and Middle Eastern philosophies and knowledge.

In Mango Street, Esperanza encounters three

curandera sisters in the short, “The Three Sisters,”

“…the symptoms of these

describing them as a group that had “power and

illnesses can be perceived

could sense what was what.”6 As they look into

her hands they identify Esperanza as having speboth as physical as well as

cial talent: “she’ll go very far.” After they ask her

psychological in nature, that

to make a wish, the sister with the marble hands

adds: “When you leave you must remember to the cause may be a tangible

come back for the others. A circle, understand?

one, or that it may well be

You will always be Esperanza. You will always be

magical.”

Mango Street. You can’t erase what you know. You

can’t forget who you are.” The curandera provides

Esperanza the impetus to begin to assume both her identities as a Mexican-American woman.

They appear to leave Esperanza with the promise of the self-knowledge she desires, and, in

this way, begin to heal her suffering. Like the curandera figures of our culture, the three sisters

tie the individual to the community. While they acknowledge Esperanza’s special talents they

remind her of how to use them for the communal good. In many ways, they are a symbol that

helps to join her personal identity with that of her community.

González, Myrna-Yamil. “Female Voices in Sandra Cisneros’ The House on Mango Street.” U.S. Latino Literature:

A Critical Guide for Students and Teachers. Ed. Harold Augenbraum and Margarite Fernández Olmos. Westport,

CT: Greenwood, 2000. 101-12. Print.

6

Cisneros, Sandra. The House on Mango Street. New York: Random House, 1989. Print.

5

Esperanza understands herself through her relation to the women who appear in her stories—it is, as it often is in our culture, a story of women teaching women. In many depictions,

Burnet | 17

Burnet | 18

Many of these things you must experience, before you understand them.

—Un curandero, Curanderismo: Mexican Folk Healing

Even without being a healer yourself, in our culture there is still the widespread acknowledgement of certain ailments and the practices to cure them. The knowledge of healing is collective and accumulated, encouraged by exchange. Susto (literally, “fright”) is among the most

common afflictions. Among others are mal de ojo (“evil eye”), or bilis (“excess of bile”). There

are common prescriptions to cure these ailments. As granddaughter to a woman who practiced the cures of healers—for example, raw, shelled eggs run down your body to rub out the

evil eye; glasses of water thrown at your back

to eliminate susto—I am familiar with how the

symptoms of these illnesses can be perceived

“There is an Anglo name for

both as physical as well as psychological in nathis, we call it sadness. But

ture, that the cause may be a tangible one, or

that it may well be magical.

this kind of sadness is

different, it is the sadness of

When I use the word “magical,” I mean to

say that those who believe in the practices of

mixed halves.”

curanderismo believe in “magic” of the kind

that is directly tied to the realm of the supernatural. For curanderas, the supernatural is a reality based on the natural forces of the universe.7 Curanderas believe that we are all born with souls and that our corporeal beings are

transient—this is not unlike Catholicism. Yet although many curanderas claim to be Catholic,

they also believe that we can solicit the aid of spirits who are no longer in their corporeal

bodies—very different than Catholicism’s view of death as final in the face of Judgment Day.

Author Ana Castillo puts it this way:

If in fact, we release our passive faith from Christian doctrine and make use of recent discoveries we have acquired through modern physics, we cease to view life as linear, hierarchical, jutting up to heaven and making divinity in our lives increasingly remote. In its

place, we instate a perception of life as being physically connected from atom to atom, no

single part being more essential nor grander than the rest and that we are all vital to each

other.7

Community understood in this way can be productive. This is what curanderismo teaches.

This is the kind of doctrine which I choose to follow, which has been my whole life. To be connected, atom to atom. It is in many ways what drives my need for words, to write down stories,

to create characters that are not only at odds with themselves, but that grasp at the mysteries of

the world in which they are formed. Yet I have been constantly at odds with what words have

the capability to express. Words have been stretched to fit what it has meant throughout my

life to both disinherit and covet the kinds of healing that curanderismo offers to me.

But there is something so artful and unexpected about curanderas that inspires in me a

belief in the power of words to express the most abstract of emotions, that truly there is some

way to articulate what is intangible in us. Castillo has this to say: “Today we are all convinced

7

Castillo, Ana. Massacre of the Dreamers: Essays on Xicanisma. 2nd ed. New York: Plume, 1995. Print.

Burnet | 19

that we are helpless in the face of the unexplainable. Yet, on the contrary, there are no mysteries experienced in life that we cannot unlock from within our own imaginations.”7

Like faith, there is no tangible way to prove that these kinds of healing practices work.

What I know is that I look in the mirror one day and see darkness. I see three days of weeping

with no origin and no end point. I see the absence of words. I don’t know where this feeling

originates; I only know of its arrival, as if it has always been with me, consuming my ability to

produce any kind of language.

If words cannot heal me then what can? This kind of darkness feels indigenous; it feels

ancient, as if I’ve been carrying it since the first shrine for Virachocha was erected. There is

something magnificent here, but it does not feel mine. It possesses me. There is an Anglo name

for this, we call it sadness. But this kind of sadness is in a different language, is it the sadness

of mixed halves.

My mother arranges a cleansing for me—una limpieza—with a curandera. The room is small,

discreetly located in the back of a spice shop. I hold a saint’s candle, I can’t remember which,

and the aroma of some kind of incense is wafting around us. The room, windowless, becomes

smoky. My head is heavy. The curandera touches my forehead with her thumb, making crosses. Her hands are browned with sun spots, a little cold, but soft, like a mother’s. She holds

my head in her hands. I let her. She smoothes branches of ruda down my arms and legs. She

whispers prayers under her breath, in a language that sometimes sounds as if it is in tongues.

It is a language that can at best be described as magical—not so much spell, but sacrament.

To believe in the act of writing stories as a way of unlocking some word that we cannot

name is to operate on a kind of faith. What I know is that when I enter the room of the curandera I feel consumed, and that when I leave it I feel as if there is some wholeness again.

***

When my grandmother passes away I find myself desperate for her stories. I feel as if I’ll

always be thirsty for those words. In the middle of one morning, with me alone in the house,

I forget that her room is empty. I get the impulse to tell her something, though I can’t remember what now, maybe to ask what she’s watching on television or whether the temperature is

okay, because it is so much like before, the house quiet and the hum of the television low in

my ear; how it is in these exact conditions that she would be napping or lying in bed as any

other day I’ve known her. I make it so far as to the hallway before I remember that she’s not

there, and I don’t know if I can explain this kind of sorrow, the desire to hear her tell me again,

“I have something to show you, just through that doorway.”

the taxonomy of home

If you didn’t grow up like I did then you don’t know,

and if you don’t know it’s probably better you don’t judge.

—Junot Díaz, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

Burnet | 20

***

When we first land in Ecuador, the scene outside of the airport in Guayaquil is big and

messy. I don’t feel at home at all, at least not how I think I should. It struck me on the plane

ride over that it had been silly to have called this country mine for sixteen years. In my first

steps onto real Ecuadorian soil, I smell gasoline and car fumes, thick and oppressive. The city

stinks of it. When we step off the plane in the Galápagos, everything inverts in its own way too. The

airport is flanked by expanses of bright, red soil. The panorama is cinematic, and color bursts

around us. The passengers load onto a boat that takes us to the main island, and when the cool

ocean spray traces my skin, it’s the first time I breathe a sigh of relief in weeks, momentarily

free from the expectation to fit, to automatically love, to know something better than I really

do. Even as we’re crossing the water, I think this must be a direct effect of the islands.

Only one English word adequately describes his transformation

of the islands from worthless to priceless: magical.

—Kurt Vonnegut, Galápagos

At the Charles Darwin Research Station, my mother and I take a walking tour through

the maze of wood pathways that loop through informative displays of the island’s flora and

fauna. Here, we observe the tame finches that led Charles Darwin to his theory of evolution.

I share his original sentiment of them when I say that they looked fairly unremarkable at the

time. It wasn’t until Darwin was back in London, puzzling over the birds, that he realized

they were all different but closely related species of finch, ultimately leading him towards

formulating the principle of natural selection. In his memoir, The Voyage of the Beagle, Darwin

noted, almost as if in awe: “One might really fancy that, from an original paucity of birds in

this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.”8

Modification. The making of a limited change in something; a change in an organism

caused by environmental factors. To speak about modification is to speak about order. Even

Ecuadorians think in terms of taxonomy, too. The citizens take great pride in being Ecuadorian and refer to themselves as ecuatorianos(-as) and gente (“people”). Despite continuing

discrimination, indigenous and black citizens identify themselves as Ecuadorians as well as

native people or black people.

The elites and those in the upper–middle classes are oriented toward education, personal

achievement, and the modern consumerism of Euro–North America. People in these classes

regard themselves as muy culto (“very cultured”), and while they may learn English, or even

French as part of their formal education, most disavow knowledge of any indigenous language. People in the upper and upper–middle classes generally identify by skin color as blanco

(“white”), to distinguish themselves from those whom they regard as below them. The prevalent concept of mestizaje is an elitist ideology of racial miscegenation, implying “whitening.”

8

Darwin, Charles. The Voyage of the Beagle. New York: Harper, 1959. Print.

Burnet | 21

Those who self–identify as white may use the term “mestizo” for themselves, as in blanco–mestizo, to show how much lighter they are than other “mestizos.”

Black people, represented by their leaders as Afro-Ecuadorians (afroecuatorianos), speak

Spanish and range through the middle to lower classes. They are concentrated in the northwest coastal province of Esmeraldas, the Chota–Mira River Valley of the northern Andes, and

the city of Guayaquil. A sizable black population lives in sectors of the Quito metropolitan

area, and there is a concentration in the Amazonian region.

As a light-skinned half-Caucasian North American (norteamericana), with a light-skinned

mother and a dark-skinned grandmother from Guayaquil, I have no idea where this puts me.

I have no idea what kind of Ecuatoriana I am, but I am at least half of one.

As I’m taking pictures next to the wooden welcome sign at the entrance of the station with

my mother, I think about how much I have her mouth, her chin, and how my family back on

the mainland has taken this as a point of reference, some sign that I belong. Even those who

aren’t related to me at all see something in me that I don’t. I’m still getting used to the idea

when I meet my mother’s first love outside of the clinic he works in as a doctor in Guayaquil.

He looks at me for a long time. He looks at me like I make him sad, and for many weeks later

it’s a look that makes me sad, too. I’m about as old as she was the last time he saw her, and as

he’s holding onto my mother’s hand I hear him telling her something that sounds like, “It’s

like seeing you again.”

I want to say, I have no idea what my face means.

One morning we hike to see the Galápagos’ famous giant tortoises. Our guide is familiar with the

“His enthusiasm is infecranch owner, who graciously leads us through his

tious. We, not naturalists,

acres. I don’t know the name of many of the plants

or trees or birds we see along the way, but up in

just tourists in our own

the highlands the moist conditions keep the epiphyte-laden environment as green as I’ve ever seen country, become naturalists

in one place. It’s not a half hour before we spot the

then too.”

first tortoise, and then the next, and then the next

after that. This is tortoise country. The ranch owner

is encouraging, smiling broadly, pointing out his finds as if it wasn’t his hundredth time. His

enthusiasm is infectious. We, not naturalists, just tourists in our own country, become naturalists then too.

We reach a shallow part where the land sags into a large pond. The terrain opens up again

for the first time in what seems like hours, and long-limbed birds flutter in groups around

the surface of the water. It’s here that we notice it near the edge of the pond, a spot where the

waist-high grasses are flattened out around a growth in the earth. The closer we walk towards

it the bigger it becomes, and the ranch owner grows excited, saying, “Look, look there, one of

the biggest!”

Burnet | 22

In the middle of the bent grasses is a huge tortoise weighing hundreds of pounds, the

topmost curve of his shell to my thigh. Everyone in the group begins to take pictures, but I’m

not sure they’re going to catch the right angle. Look at this thing, I want to say. A champion

of evolution. There are many things that I don’t remember of this moment. I don’t remember,

for instance, the time of day. I don’t remember the temperature. I don’t remember the location

of the tortoise well enough to point it out on a map. I don’t remember if anyone had anything

important to say. I don’t remember how long we stayed in place, watching how a thing does

not move.

What I remember is this: a smooth, grooved

“I don’t remember how long we

shell. I think the hexagonal patterns that make

stayed in one place,

up its life-hood are a better map than any of us

have. We sit with it for a while, lightly grazing watching how a thing does not

its back with our fingertips. It’s still inexplicable, that feeling, that putting a hand on it felt move. What I remember is this:

like putting a finger to the very center of the

a smooth, grooved shell.”

world.

When we finish our hike, we climb to the top of the hill where the owner operates a restaurant on a large patio covered by tin rooftops. Along the veranda the view is spectacular, and I

think this must be the stuff of movies, not real stuff, and the rain is going in and out with the

sun, occasionally littering the patio with the sounds of raindrops hitting the metal roof. It’s as

if the islands can’t sit still, continuing to evolve even from their fixed spot on the earth. When

our guide joins us and the owner again on the patio, they point out an enormous tortoise shell,

a skeleton, sitting in the middle of the room.

“The tourists love it,” the owner says, encouraging us to crawl inside of it for a photo-op.

It’s almost, but not quite, as big as the shell of the tortoise we’ve just seen. Observing the

smooth yellow-brown skin of the dead shell, I’m struck with the sudden feeling of disaster. I

wait for tornadoes to touch down, or volcanoes to explode, but nothing ever comes. It’s just a

dead thing that was alive once, no champion.

Vonnegut writes about this perfect futility in his novel Galàpagos, describing:

As she had often told her students, sailing ships bound across the Pacific used to stop off

in the Galàpagos Islands to capture defenseless tortoises, who could live on their backs

without food or water for months. They were so slow and tame and huge and plentiful.

The sailors would capsize them without fear of being bitten or clawed. Then they would

drag them down to waiting longboats on the shore, using the animals’ own useless suits of

armor for sleds. They would store them on their backs in the dark paying no further attention to them until it was time for them to be eaten. The beauty of the tortoises to the sailors

was that they were fresh meat which did not have to be refrigerated or eaten right away.9

My brother, enthusiastic, climbs into the shell while my mother holds a camera, snapping

pictures of him trying to lift it on all fours. They take pictures while I lean against the veran9

da. It’s the guide who notices me standing away from them while they take their pictures,

saying something with a flash of a smile like, “No picture? You’ll like it.”

“No, no picture.” I shrug, saying this like I say everything to adults, awkwardly and hoping I don’t have to repeat myself. From my distance, I catch only a few words of the conversation behind me, the smallest sigh from the owner and how “the dogs eat their eggs sometimes

you know.”

I’m not sure that we can resist how we are versions of the same thing, modified to fit the

best we can; I’m not sure if, despite this, we are still forced into some kind of order.

I’ve written this story more than once. Each time, I find something new in how things happened. The things I remember most strongly now are different from before, and sometimes it

feels as if I’m collecting an immeasurable amount of small moments so that I’ll have enough to

last me until the next time I can go back—so I can conjure up this feeling of belonging at will.

It’s very likely that I might never see this country again. Since that time, many of the people in

the stories I knew have passed on, moved, or vanished. In this world that’s always spinning,

it’s inevitable, this projectile motion away from the things that were once held close. I feel now

the need to preserve, to keep, to covet.

In Mango Street, Esperanza discovers herself through writing. On her death bed, her Aunt

reminds her: “You just remember to keep writing, Esperanza. You must keep writing. It will

keep you free, and I said yes, but at the time I didn’t know what she meant.” Writing would

lead to her liberation, a gesture which proves to be true by the close of the text. It’s through

writing that Esperanza discovers who she is and affirms her identity—it is how she finds her

home. Esperanza inhabits the house of storytelling: “I like to tell stories. I tell them inside my

head…I make a story for my life, for each step my brown shoes take…I am going to tell you

a story about a girl who didn’t want to belong.” Through her chronicles of Mango Street, she

illustrates the realization of her identity through writing. In this way, Esperanza solves the

problem of the “between-world” by discovering that her homeland is mythical and spiritual,

not tied to a locality or physical space.

I don’t know if it is all that easy. I come back to a recent conversation I share with my

mother where she says, “Mija, you are so americana. And I am so hispana.” She says this as if

my whiteness in some way makes her more Hispanic. She says this in a sad way, as if white

culture has eliminated everything that I was taught. She says, “It’s not your fault. You grew

up away from your mother.”

Perhaps a mixed person is doomed to always be unsatisfactorily whole for either half. I

don’t know. I don’t have any answers. I only know that I must continue to write, perhaps in

the hope of some kind of reconciliation. My grandmother used to say, que sea lo que dios quiera, (“let it be in God’s hands”). I don’t know these hands particularly, where or how or what

shape they take; what I know is that these stories—her stories—have been for me a kind of

knowing. I would say, let it be in what the story remembers, in what it makes real again.

Vonnegut, Kurt. Galápagos: A Novel. New York: Delacorte P, 1985. Print.

Burnet | 23

Back to Table of Contents

Burnet | 24

At WindanSea Beach, La Jolla |

Kirby Wright

I drape my towel

Over a boulder

Above the strand.

I have exiled myself

From the ocean,

Where surfers

Dodge exposed reef.

The scent

Of coconut lotion

Mixes with the stink

Of rotting kelp.

My dyed hair

Glints purple.

Varicose veins swell.

I am invisible

To bikinis catwalking

The hourglass shore.

They know everything

And nothing.

I have forgotten

The little I know.

I do remember

Hips bucking

After the prom.

Years drown

In the emerald sea.

I am a wrinkle

Perched on stone

Soon requiring

A firm hand

To scatter, to fill

Raging surf with ashes.

The tide retreats—

Bikinis vanish

Behind a ledge.

Garlands of kelp

Wave from the shallows.

Pinter | 25

Back to Table of Contents

Wright | 26

Life Writing as Performance Art: Narratives of

Romance in Spoken Word | Christine Estima

L

ayne Coleman, former Artistic Director of Theatre Passe Muraille in Toronto, Canada,

once said to me, “We used to throw rocks at our lovers’ window. Now, we text message.”

Indeed, that sentiment can be applied to many forms of communication and forms of

life writing that have fallen into decline with the rise, permeation, and ease of use that is modern technology. It is with that in mind that I approach the current state of life writing and life

writing theory. An avid diarist and proponent of letters, I too have been asked why I bother to

record with the pen, rather than with the digital camera. Why the postcard and not the email?

Why the typewriter and not the laptop?

In the October 26, 2013 edition of The Times of London, columnist Libby Purves postulated,

“Emails, and beyond them text messages, are eroding an art refined since Pliny and Petrarch.

Would a modern Lord Chesterfield take such elegant trouble if he was sending emails to his

wayward son? Would the passion of Napoleon still reach across the centuries to move us, if he

had tapped it out on a keyboard?” (12).

Adding to this sentiment, Simon Garfield

of the University of Sussex writes in his book

“Among the tables of antique

To the Letter: A Journey Through a Vanishing

vases, rusted tea tins, and

World:

second-hand oak furniture,

What have we lost, psychologically, by no

longer owning our mail in physical form?

I was forfortuitous

Is a hand-held ink-written letter more valuenough to find, on two

able to our sense of self and worth on the

planet than something sent to a fortress of separate occasions, a series of

cables in the Midwest that likes to call itself

handwritten love letters.”

“a cloud?”…There is an intrinsic integrity

about letters…the application of hand to

paper, or the rolling of the paper through the typewriter, the perceptive gathering of purpose (19, 21-22).

In September 2013 whilst I was temporarily living in Brussels, I discovered the Jeu de Balle,

a flea market that occurs every single day in a quarter near the Bruxelles-Midi train station.

Amongst the tables of antique vases, rusted tea tins, and second-hand oak furniture, I was fortuitous enough to find, on two separate occasions, a series of handwritten love letters. The first

set was between a man named Kenneth and a woman named Nathalie, and date from 1978 up

to 1997. The second was written by an unnamed man to an unnamed woman on August 20,

1945. I translated them from their original French and found that they were letters of adoration, letters of parting and goodbyes, letters of lust and desire, and letters of longing. It struck

me that these are precious and highly unusual finds, and that in my own personal possession

Estima | 27

are possibly only two or three handwritten letters addressed to me that could be compared or

even at best keep company with such epic letters of admiration and love. I realized that such

practices are lost on my generation. The rise in technology and ease of email has removed the

need for letters, and has increased the disposable nature of conversation, communication and

correspondence.

But surely the need to still express

these deep-seated emotions and relations

to our loved ones—a guttural instinct that

exists within all of humanity—still exists

amongst my generation: the last generation to use vinyl records and cassette

tapes, the last generation to learn how to

type on a typewriter, the last generation to

own a radio before a television. Surely my

generation, adapting with the times, has

morphed the culture of letters into a more

twenty-first century version.

“Has the current zeitgeist

morphed the need for the

recording of personal affairs from

a private practice to a public one?

From a written

experience to a verbal one?”

One of the underground but increasingly popular events to come out of my generation is

the storytelling performance art phenomenon. Over the past four decades, spoken word has

developed into an increasingly popular and complex art form. In theoretical and critical dis

course, theorists like Dr. Cornelia Gräbner argue that it is an independent performance genre;

others like Dr. Gaston Franssen treat it as a contemporary manifestation of poetic declamation

or recitation. The most notorious spoken word event occurs in New York City and is called

The Moth. Its rules are simple: adhering to a new theme each week, members of the public are

invited to tell true stories from their lives in front of an audience, and the resulting collection

of narratives are recorded for a podcast which is added to the internet later as a free download.

The Moth often sees storytellers recount tales of love: love triumphant, love strained, love lost,

love remembered. Around the world, similar storytelling spoken word events have popped

up, such as Spark London in the United Kingdom, and Raconteurs in Toronto, Canada.

Has the current zeitgeist morphed the need for the recording of personal affairs from a

private practice to a public one? From a written experience to a verbal one? In The Good Psychologist, Noam Shpancer writes, “Memory is not a storage place but a story we tell ourselves

in retrospect. As such, it is made of storytelling materials: embroidery and forgery, perplexity

and urgency, revelation and darkness” (38).

The objective of life writing is to emphasize the representation of one’s own romantic

past within a medium that complements the climate in which it emerges, and that climate has

metamorphosed from traditional life writing methods to performative methods. The craft of

letter writing has undergone a remarkable mutation from the pen to the microphone, from the

page to the stage: still true life, still framed within memory and bias, and potent enough to

echo through the ages. What once was private is now public. What once was written is now

verbal. To put a fine point on it: spoken word is the new love letter.

Estima | 28

In the August 14, 2009 online edition of The New York Times, columnist Alex Williams

quotes Anthony King, the Artistic Director of the Upright Citizens Brigade Theater, on the

topic of The Moth: “Storytelling in this manner has apparently become so relevant to the moment that it can no longer be confined to a few sporadic events populated by a small group of

would-be memoirists. After all, it’s basically just confession.”

In the June 14, 2012 edition of The New Yorker columnist Nathan Englander says of The

Moth, “…what they are doing is tapping into something fundamentally human and fundamentally social. It is the urge to both share and receive word of our common experience.” He

goes on to say:

…in most cases, there is a special kind of intimacy to that one-on-one, piped-directly-toyour-brain feeling….Each time I listen to a story told aloud, and feel that direct connection

with the teller, I am reminded of what a story, well told, can do….It’s not the same as holding court over dinner, or sharing something funny at a bar….And, as with any other craft,

it only works if that sense of self, that idea of performance, falls away.

One of the many examples of true storytelling pieces being used in the place of love letters

comes from Adam Gopnik, who performed the piece “Rare Romance, Well-Done Marriage”

at The Moth in New York in 2011, which is one of the better examples of a performer using live

storytelling to “write” a love letter. Gopnik, who is a columnist for The New Yorker, talks about

his need to have his steaks prepared rare, whilst he finds his wife Martha’s desire to have all

her steaks prepared well-done the kind of preference reserved for blue-collar, tasteless plebes.

Of course, this is all tongue-in-cheek, steeped in metaphor, and fashioned as a love letter to

his long-suffering wife. He equates what she finds tasteful to her senses as morally distasteful

to his senses. “I say this with shame,” he orates, “she likes everything well-done. She would

say ‘well-done’ when we would go out to a restaurant in Montreal, and they’d bring it to her

well-done, and I’d smile and think ‘we’ll get past this.” He notes that within the realm of young

love and passion, everything that you share and exchange with your partner is “rare” anyway,

to use the technical culinary term. He qualifies her morally-inferior choice for well-done meat

by admitting that “we got married anyway.”

After preparing a tuna au poivre meal for his wife and two children one night, where the

tuna was pink in the middle, and the entire family recoiled at the under-cooked nature of the

fish, Gopnik says the symbolism and allusion found within the pink meat is obvious: when

you offer someone something pink, you are offering them your sexuality, and when they reject it, they are rejecting you. The hilarity ensues when he gets up and storms off, but his wife

corners him into finishing the fish, and he begrudgingly puts his apron back on and cooks the

tuna until it is indistinguishable from canned tuna:

But that moment was a hinge moment, a pivot moment. If you’re married, you know those

moments. Where you both say, “We can’t go there. If we go any farther in that direction,

we’ll end up apart.” But I noticed after that moment, that when we’d go out to restaurants,

Martha would use an extraordinary word that she had never used before that’s essential

to the continuity of a marriage, and that word is “medium.”

Estima | 29

As Gopnik looked lovingly in his wife’s eyes, he decided to stop sautéing, and began to

braise everything, saying, “Because that’s what every marriage seeks to be. We start off in the

wonderful, blazing, raw intensity of sautéing, and work our way to the beautiful tenderness

of the braise and the stew. In those juices, we renew our vows.”

Joyce Maynard, an author from New York City, performed the piece “Love is the Best Art

of All” at The Moth in 2005. She crafts it as a love letter to her children, as she describes how

she, like her parents before her, protected her children from all kinds of pain, to the point of

perhaps obsession or over-compensation. As someone who feels her children’s pain on her

own nerve endings, she describes the lengths she went to, before the advent of the internet, to

procure rare and obscure toys for her children on birthdays and Christmases, which included

driving across the country and back again in one day just to purchase a toy. The epiphany of

her narrative occurs when she takes her children to London and encourages them to purchase

one item to commemorate their time abroad. Her son chooses brightly coloured leather juggling balls:

We went down into the London tube and

he began to juggle with the juggling balls,

“‘And as I was climbing out

and I knew so well the kinds of things that

of the pit, with my daughter

could happen, and how I would feel if they

did, that I screamed out to him, “No Charstanding on the edge

lie, don’t!” but it was too late. One of the

beautiful leather juggling balls fell into the

screaming at me, I knew I had

pit of the London tube. And I jumped in

become an insane mother.’”

after it. And as I was climbing out the pit,

with my daughter standing on the edge

screaming at me, I knew I had become an

insane mother.

Maynard only admits her limits as a mother when she has to tell her children that she is

divorcing their father:

That’s when I knew the utter foolishness of ever supposing that I could protect my children from the real pain, and the folly of having tried so long…But here’s the thing that

has occurred to me, and it’s a wonderful discovery and revelation and has brought some

peace. Although I did a lousy job of protecting them, I am in fact related by blood to three

surprising happy, healthy individuals. It occurred to me as I looked out to them as adults

that the very things I tried to protect them from, sorrow and disappointment that every

one of us goes through, are also the things that made me who I am. So if I could do it again,

my goal would no longer be to save them from loss and pain, but to raise them to survive

it.

Brian Finkelstein, in 2004, performed “How I Earned My Bitter Badge” at The Moth in New

York City. It is fashioned as a love letter to Samina, a woman he was in a “four year platonic

relationship” with, and then was forced to travel to India to watch her get married to someone else. He lovingly describes her: “I saw Samina. The very first time I saw her, it’s hard to

describe why you love people, but she was beautiful. She smiled at me; I was completely par-

Estima | 30

alyzed; I was frozen, and I’d never felt that, and I’ve still never felt that. And I’m never gonna

feel it. But I felt it. And if anyone wants to try, I’m available.”

We must pause here to ponder if Finkelstein, like Gopnik and Maynard before him, chose

his words with the understanding that his object of affection would hear his words. With that

in mind, we can fully understand the choice of language and the ardent passion employed

here, as he clearly seems to want Samina to know, albeit indirectly, that she was perfection to

him. After being told that she was Muslim, was arranged to be married to someone else, and

that they would have to remain just friends, Finkelstein replied, “Cool.” They embarked on

this friendship:

It was beautiful. We spent all our time together. She was everything that I wasn’t. She was

90210 on Wednesday and Gap and George Michael, and I was like Bukowski and dirty. I

quit smoking and I quit drinking and we saw movies and we talked on the phone, and it

was beautiful. It was the best relationship. There was no physical contact, but that was ok

because I’d had enough vampire girls in San Diego.

He travels to India over the Christmas holiday to meet her family and attend her wedding,

which takes place over three days. In a quiet revelation, he talks about discovering Samina’s

betrayal: she had slept with another man and was worried she might be pregnant. This unknown man was also told that they would have to remain friends because she was betrothed,

but he ignored it. Her fiancé feels betrayed; Finkelstein feels betrayed and talks about his

heartbreak:

She’s telling me this and I realize I’m not in a love-triangle like I thought, I’m in a lovesquare. Only my corner is the one without any sex, apparently. And I realized that I’m

living a lie. I light a cigarette, grab my backpack, and I head into the streets of India. I go to

the airport, I buy a ticket and visa to Nepal. I go to Kathmandu and go up the mountains in

the Himalayas. I get up there, and I’m on top of the world, literally. And I start thinking,

“What am I doing here?” And I start to cry. And I start to laugh. And then I throw up.

Novelist Meg Wolitzer told her story “First Love, Long Island, 1975” at The Moth in 2005.

She speaks this love letter to a boy she met at sleep-away camp in the Catskills named David, who became her first boyfriend and who she describes

as very sweet and kind. Back then boys and girls who dated

had “bases.” That old baseball metaphor applied to dating as

“Back then boys and

“things that were happening to you.” They kissed you: first

base. They touched your boobs: second base, and they put

girls who dated had

their hands in you like a sock puppet: third base. “It was all

‘bases.’”

things that were happening to you; you were this passive person,” she describes.

When David became obsessed with the bases idea and “going to third” with her, she decided that doing it might be a “feminist statement,” as she puts it, and so she agreed that one

day, she and her first love would do the holiest of holies. Wolitzer’s framing and retelling of

this story is styled as a nostalgia-ultra-acolyte, that this was a time when love was young and

innocent and untainted by adult demands. So while she really did love her young boyfriend

Estima | 31

David, she performs this piece as if to remind us that this kind of love still exists within all of

us. She recounts:

Maybe I was going along with it. Maybe it wasn’t a feminist thought. I felt like I was lying

there, on this little bed, like a passive girl. And all of our adorable puppy-love passion was

being taken over by this horrible thing that we decided to do in this freakish negotiated

way. I thought, no, this isn’t what I want to do. So before I left, I said, “I don’t think you

know how to treat women.”

She summarizes, as an adult, how this kind of dating ritual doesn’t exist in adulthood,

“There are no bases anymore. That’s the sad thing about adulthood. There’s nothing to aspire

to in that way. It’s all a big open field, there are no bases, the bases have been removed.”

These performances from The Moth are meaning-potent, fire-infused, and steeped in the

manner of language and ardent love previously employed solely in love letters. Who among

us can say we have sent text messages approaching this kind of fervent passion? As a final example, I submit to you a spoken word piece of my own making. I performed the piece “Space

Invaders” at the Spark London live storytelling event in 2013, and it details the creation and the

dissolution of one of the greatest love affairs of my life. It was indeed fashioned as a love letter

to my former flame, albeit a goodbye-love-letter. My performance was uploaded to YouTube,

but I have no idea if he has seen it. I don’t need to know. I didn’t perform the piece with the

intention of him finding it one day. These are all the things I never could write privately. The

only kind of catharsis I could afford was to publicly and verbally express all the emotions that

lacked on the page.

Englander, Nathan. “Stories that will Plain Curl your Eyelashes: A Love Letter to The Moth.” New Yorker. 14

June 2012. Web. 1 Oct. 2013.

Finkelstein, Brian. How I Earned My Bitter Badge. themoth.org. Moth, 18 Feb. 2004. Web.1 Oct. 2013.

Franssen, Gaston. “The Performance of Poeticity: Stage Fright and Text Anxiety in Dutch Performance Poetry

since the 1960s.” Authorship 1.2 (2012): n. pag. Web. 1 Oct. 2013.

Garfield, Simon. To the Letter: A Journey Through a Vanishing World. London: Canongate, 2013. Print.

Gopnik, Adam. Rare Romance, Well-Done Marriage. themoth.org. Moth, 13 Sept. 2011. Web. 1 Oct. 2013.

Gräbner, Cornelia. “Public poetry performances of the 1970s and 1980s: reconsiderations of poetic licence.”

Lírica i deslírica: Anàlisis i propostes de la poesia d’experimentacio. Ed. Margalida Pons. Palma de Mallorca: U of the

Balearic Islands P, 2012. Lancaster U. Web. 1 Oct. 2013.

Maynard, Joyce. Love is the Best Art of All. themoth.org. Moth, 13 Dec. 2005. Web. 1 Oct. 2013.

Purves, Libby. “Signed, sealed, delivered.” Times of London. 26 Oct. 2013: 12. Print.

Shpancer, Noam. The Good Psychologist. New York: Henry Holt, 2010. Print.

Williams, Alex. “Going Solo Gets Crowded: Storytellers Finding Success on Stages Big and Small.” New York

Times. New York Times, 14 Aug. 2009: ST1. Web. 1 Oct. 2013.

Wolitzer, Meg. First Love, Long Island, 1975. themoth.org. Moth, 18 Jan. 2005. Web. 1 Oct. 2013.

Back to Table of Contents

Estima | 32