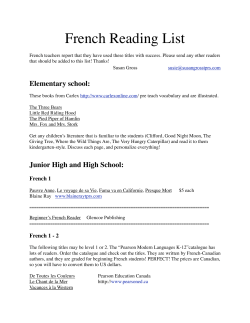

1 Premises