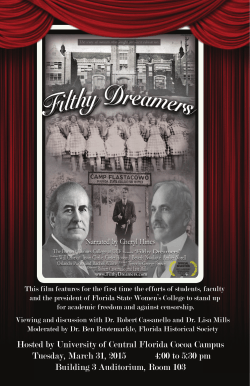

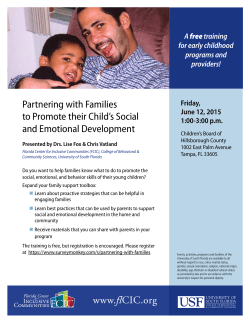

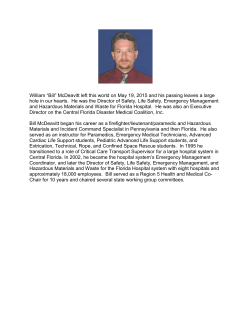

final order