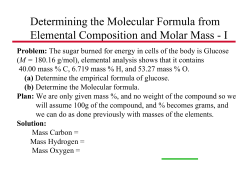

Calculations In Chemistry Modules 8 to 10