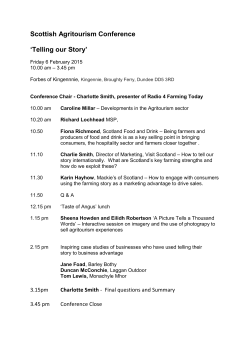

SCOTLAND: Myths Realities Radical Future