in time for the 2015 Pan / Parapan american Games this

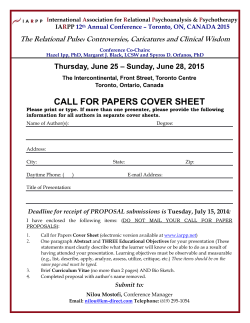

instant city In time for the 2015 Pan / Parapan American Games this summer, Toronto’s waterfront is ready for its biggest reveal yet: a whole new neighbourhood in the east end, and a slew of other major projects happening along the shore By Elizabeth Pagliacolo Clear Spirit Condominium, Distillery District Canary District Condos, by KPMB Victory Soya Mills Silos, heritage buildings Lake Ontario Future site of Canary District Condos, by KPMB Architects When the games begin in July, athletes from 41 countries will sleep on bunk beds set up in the brand new condos, college dorms and townhouses that make up the Canary District. The neighbourhood is built on reclaimed industrial land, just a 15‑minute streetcar ride from downtown. 84 may 2015 P84-92_PanAm_MAY15_F.indd 84 2015-03-06 3:15 PM Fred Victor affordable housing, by Daoust Lestage George Brown College residence, by architectsAlliance Canary heritage building YMCA community centre, by MacLennan Jaunkalns Miller Architects Wigwamen affordable housing, by Daoust Lestage PHOTO BY tom arban Front Street Promenade may 2015 85 P84-92_PanAm_MAY15_F.indd 85 2015-03-09 12:57 PM of Toronto’s KPMB Architects is addressing a roomful of developers, planners and journalists who have made the trek to the Rotman School of Management on a cold night in January to find out how the city’s site for the pending Pan/Parapan American Games is shaping up. “You have to believe in the people on your team,” he says. “You get to the game, and you bring everything you’ve got.” If any project merits the sports metaphors, it’s the Athletes’ Village, built on the east side of the city’s downtown core by Dundee Kilmer Developments in just 36 months – overnight in urban planning terms. The district at this time of year is still shrouded in snow, its glass buildings resembling architectural icebergs. A few days after the presentation, journalists were invited to crunch through the snow, and to engage in a dead-ofwinter version of the question that has preoccupied the site’s planners for three years: what will this place be like when it’s full of people? While sports fans will be focused on the games, 10,000 athletes and team officials from 41 countries will have the run of this built-from-scratch neighbourhood. The athletes will claim their bunk beds in otherwise empty 86 may 2015 P84-92_PanAm_MAY15_F.indd 86 condos; they’ll share meals in a makeshift dining tent; and they will be bused out to the official sports facilities spread across the Greater Toronto Area and beyond. But to see how the village truly performs, we will have to keep watching long after the games end. In early 2016, the cluster of condos will be rebranded as the Canary District, and construction crews will step in to apply the final finishes (including installing the kitchens) before residents move in. Essentially, some 1,563 people will settle into this instant city, the first wave of many neighbourhoods to come. “Cohesive diversity” is the buzz phrase architects and developers have been lobbing about to describe the project. By having the buildings designed by multiple firms – KPMB, architectsAlliance, Daoust Lestage and MacLennan Jaunkalns Miller – the aim is to achieve an assortment of structures. Ironically, this modern LEED Gold community begins with a gateway formed by two historic landmarks: the 1858 red-brick Canary restaurant and an old railway building across the street. Front Street has been extended to form a wide promenade separating two rows of discrete blocks. Toronto firm architectsAlliance designed the most outwardly exuberant building, the George Brown College residence. With an entrance propped photo by Tom Arban “It’s high-speed urbanism and design,” says Bruce Kuwabara. The principal azuremagazine.com 2015-03-06 3:16 PM Top photo by Zero Fractal Studio, bottom photos by Tom Arban ← The George Brown College residence, by architects Alliance, will house 500 students after the games. → One of the River City condominiums, by Saucier + Perrotte. Developed by Urban Capital, the black-clad midrises were the first to stake a claim in the east end. Phase three will soon break ground with another dramatic S+P building, called RC3. ↓ A view of Lake Ontario from the rooftop of the George Brown College Water front Campus. The school is about a 20-minute walk from the new residence. ↘↘ The city hopes to attract tenants from the high-tech sector with ultra-high-speed bandwidth capabilities at the Waterfront Innovation Centre, one of the more eye-catching office complex proposals, designed by Sweeny &Co of Toronto. on a cross-hatch of concrete pillars, the L-shaped seven-storey complex is set on top of a YMCA community centre designed by MacLennan Jaunkalns Miller, also of Toronto. KPMB designed two condominium developments, one featuring a pair of mid-rise buildings made up of Jenga-like stacks; and two affordable rental properties, designed by Montreal’s Daoust Lestage, feature super-sized floor numbers cascading down their facades, and colourful archways that allow people to walk through one building to the other. Moving residents through, over and under buildings, and into shared green space, is the master plan’s stroke of genius. The neighbourhood is capped by a public park, Corktown Common, and it will be served by a new streetcar loop. It will also be wired to the hilt, with a broadband network and one of the fastest internet speeds in North America. Zoom out from the marketing hype, and Athletes’ Village/Canary District is Waterfront Toronto’s most prominent development and the face of the city’s eastward expansion. Nearby, River City, 1,100 units designed by Saucier + Perrotte of Montreal, continues to take shape. Launched by developer Urban Capital before Toronto won the Pan Am bid in 2009, the private project was a first foray into this no man’s land. “There was absolutely nothing, except pink pipes coming out of the ground,” recalls principal Gilles Saucier. From the shard-like black mass of the first buildings to the drawer-like units and balconies that define the latest tower, RC3, these are radical and visionary for a city with far too many predictable towers. River City’s best idea – to place social and playground amenities (including basketball hoops and skateboard ramps) underneath the Gardiner Expressway – was so ingenious the city ran with it, and turned it into Underpass Park. The dynamic programming that now defines the east end is the result of long-vision planning and commitment in the face of controversy. Since it was formed in 2001, Waterfront Toronto has opened up the city and re-naturalized former industrial dead zones. The completion of Athletes’ Village, on budget ($709 million) and on schedule, is more than just a milestone; it’s a vindication for an organization that has come under fire from gravy train–obsessed politicians who point out overspending with not enough signs of progress. To Torontonians, the construction seems endless, until you consider that the 800‑hectare site is the largest continuous project (continued on page 90) may 2015 87 P84-92_PanAm_MAY15_F.indd 87 2015-03-06 3:16 PM Aven ue Spad ina Toronto’s 800-hectare lakeshore development is the largest in the world. These major projects are redefining the new blue edge. Bat hur st S tree t At the Water's Edge Rogers Centre CN Tower L Tower This 58-storey blue laminated glass tower by Daniel Libeskind was recently topped off, and residents will begin moving in this summer. Billy Bishop Pedestrian Tunnel Designed by Patkau Architects of Vancouver and Kearns Mancini of Toronto, the new entrance to the 222-year-old historic site is located at the city’s former shoreline. Queens Quay West Where airline passengers used to take a short ferry ride to reach the island airport, they can now glide between terminal and shore on four underground moving sidewalks. The new tunnel, 30.5 metres beneath the harbour, makes for a six-minute journey from end to end. P84-92_PanAm_MAY15_F.indd 88 Plans are afoot to turn the Toronto Island ferry dock into an architectural showstopper. Five dream teams have been shortlisted: • Clement Blanchet (Paris), Batlle i Roig (Barcelona), RVTR (Toronto) • Diller Scofidio + Renfro (New York), architectsAlliance (Toronto) • West 8 (Rotterdam); KPMB and Greenberg Consultants (Toronto) • aLLDesign (London); Quadrangle and Janet Rosenberg & Studio (Toronto) • Stoss Landscape Urbanism (Boston), nArchitects (New York), ZAS Architects (Toronto) One Yonge For almost three years, this touristic boulevard has been marred by construction. By the time the Pan Am Games arrive, the 1.7‑kilometre road will integrate various forms of travel, including a dedicated bike path along a tree-lined promenade with sidewalks paved in granite. Still to come: five footbridges, designed by West 8 of the Netherlands and local firm DTAH, linking the inner harbour’s slip basins and inlets into one continuous pedestrian route. 88 may 2015 Jack Layton Ferry Terminal Developer Pinnacle International plans to build Canada’s largest luxury residential complex at the foot of Yonge Street. The design by local firm Hariri Pontarini squeezes six towers, between 40 and 88 storeys, into one block. Now under review by the city, the project must overcome a few more obstacles before it gets the green light, including rerouting a freeway ramp to make way for an expanded promenade. map courtesy of waterfront Toronto / edited by taylor kristan Fort York Visitor Centre azuremagazine.com 2015-03-09 12:58 PM eet ent Str Parliam ne Street Sherbour Yonge Street 1 2 3 6 4 5 5 East Bayfront Developments Pier 27 One of the more playful condo developments is designed by architects Alliance. More than 300 units fill two sets of glass slab volumes; each pair of 11-storey buildings is joined by a three-storey-high skybridge, where the penthouse units will reside. The $55-million complex, which primarily contains single and one-bedroom units, is by Cityzen Development Group and Fernbrook Homes. Waterfront Innovation Centre As part of a master plan by inter national architects Hines and Pelli Clarke Pelli, some 1,800 occupants will call Bayside home in the next decade. The first building of six residential and two office mid-rises is Aqualina, a 13-storey condo designed by global firm Arquitectonica, expected to be finished by 2016. River City Canary District / Athletes’ Village Toronto fast-tracked this major east side development and the neighbouring areas to finish in time for the Pan Am Games, where the buildings will host athletes from 41 countries before residents, owners, tenants and students move in next year. 1 YMCA community centre 2 George Brown College residence 3 Affordable housing 4Condominiums 5 Future condominiums 6 Corktown Common Park Keating Channel The city hopes to lure such tech brands as Google and Ubisoft to this jewel-like complex, which offers a sleek environment for up to 2,000 employees. Construction of the centre, designed by Sweeny &Co, remains on hold until at least half of the space is leased. Meanwhile, groundbreaking is planned for 2016. If all goes according to plan and downtown Toronto keeps growing eastward, this will be the next big neighbourhood to emerge, transforming 125 hectares of industrial wasteland into a mixeduse district with 4,700 residential units. This $383-million development by Urban Capital is creating 1,100 loft-style condos and townhomes in a cluster of buildings by Saucier + Perrotte of Montreal. Phase three, now underway, is a 29-storey structure called RC3, shaped like a boot with jutting balconies that resemble stacked USB keys. may 2015 89 P84-92_PanAm_MAY15_F.indd 89 2015-03-09 12:58 PM George Brown College’s school of health sciences, completed in 2013. The highly transparent building, designed by KPMB, is now used by 3,500 students. It was among the first non-residential projects completed along the lakeshore. in the world. As each of its more photogenic components is unveiled – the WaveDecks, Sugar Beach, Corktown Common – the bigger picture of laying groundwork to connect the three major precincts of Central Waterfront, East Bayfront and West Don Lands has continued more quietly. For 15 years, industrial zones have been remediated, streets repaved, sewer systems installed and trees planted to create one cohesive fabric. Most important, the vibrant parks and public spaces were carved out first, before private developers could come rushing in – and, thanks to the established infrastructure, they have. When all is said and done, the waterfront will be home to 40,000 residential units and one million square metres of commercial space, and it has already attracted $2.6 billion in private investment, twice the initial amount of public financing. The recently announced Waterfront Innovation Centre, designed by Sweeny &Co of Toronto and funded by Menkes Developments, is expected to attract more jobs and tenants in the creative and tech sectors. As of yet, there are no swooping Zaha Hadid buildings or shiny Anish Kapoor beans. For all its Jacobsian “eyes on the street” urban planning, the Athletes’ Village exudes typical Toronto modernism, a multiplication of glass boxes with nary a curve or odd detail. “We knew if we could 90 may 2015 P84-92_PanAm_MAY15_F.indd 90 deliver this project for the lowest amount in terms of public expenditure, that would be a compelling proposition,” says Peter Clewes, principal at architectsAlliance, whose pragmatic viewpoint is widely held by local developers and architects. To reduce time and labour costs, the buildings employ standardized components and off-the-shelf exterior wall systems. And they have been selling before the games, to avoid the stagnant fate of Vancouver’s village after the Winter Olympics. Rather than statement buildings, the vision is to build a tapestry of small but impactful moments. Finally slated for completion in June, the revamped Queens Quay, southwest of the downtown core, will unite streetcar tracks with a lakeside bike path and sidewalks paved in a granite pattern of giant maple leaves. The entire 1.7‑kilometre stretch will be lined by a double allée of trees, fed by an underground irrigation system. This green-canopied spine, part of a master plan by Dutch firm West 8, will transform the central waterfront, right down to the details. “Before we started, the street furniture was ridiculous,” says Samantha Gileno, former communications manager for Waterfront Toronto. “We counted something like 60 different garbage cans, light poles, benches, public-private furniture – no consistency whatsoever. So one of the big moves (and it’s nothing azuremagazine.com 2015-03-06 3:16 PM outrageous) is about creating consistency along the way so people know this is public space.” It’s also about building a future city that is walkable, high tech and affordable. In this respect, the waterfront development is ahead of its time, and then some. “This city is growing south and east,” Kuwabara explained to that packed room in January. “For the past 20 years, we grew west; Frank Lloyd Wright said all cities grow west, except L.A. But the mouth of the Don River is the future of the city. We’re reinventing the city.” He’s not exaggerating. Waterfront Toronto’s next significant project is to re-naturalize the mouth of the Don and flood-proof the surrounding industrial lands and adjacent neighbourhoods. Within a decade, we will see this bizarre landscape of massive silos, beaches, parks and sailing clubs scattered across 125 hectares of depressing concrete morph into mixed-use communities with lush parkland, all connected to the rest of the city by public transit. The initial master plan was approved in 2010, after New York landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh and urban designer Ken Greenberg 92 may 2015 P84-92_PanAm_MAY15_F.indd 92 won the international competition. Waterfront Toronto wasn’t moving fast enough for former mayor Rob Ford and his brother, Doug, who stepped in with dreams of their own, starring a Ferris wheel, and a monorail straight out of an episode of The Simpsons. Their showboating forced Waterfront Toronto to renegotiate its meticulously planned, environmentally sound vision. “They insisted on a value-engineered plan, which shrank the landscape a little, taking out the river’s curvilinear nature and containing the landscape in more of a box,” explains Greenberg. “Parts of the changes addressed technical issues, and parts were just in aid of political face saving.” But he is happy that the essence of the plan has survived. For Greenberg, the assertions from politicians that nothing is happening on the waterfront are laughable. “It couldn’t be further from the truth. Transformation takes decades,” he says. “Waterfronts all across North America are being reinvented.” As for Michael Van Valkenburgh, news that the environmental assessment to naturalize the Don is now approved has him excited: “We’re chomping at the bit to get started. Toronto has a passionate public, and it’s time to give them back something good.” Bottom left photo by Guillaume Paradis, Bottom right photo by Tom Arban ← In place for a few years now, West 8’s WaveDecks are located along Queens Quay, one of the most tourist-friendly strips on the waterfront. The high-traffic promenade will be completed this June, with a 1.7-kilometre allée, fed by an underground system of Silva Cells to ensure that the trees mature and thrive. ↙ Sugar Beach, a triangular park filled with pink umbrellas and white sand, has won numerous awards since it opened. The park was designed by Claude Cormier + Associés of Montreal. ↓ Pier 27, two sets of buildings, each topped with a three-storey horizontal tower. The design by architects Alliance maximizes views of the lake with surrounding parkland that invites passersby to wander down to the water’s edge. azuremagazine.com 2015-03-06 3:16 PM

© Copyright 2026