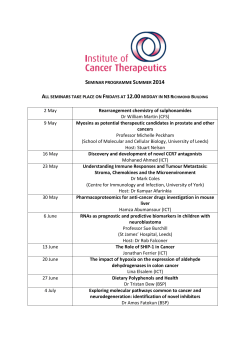

Document 169830