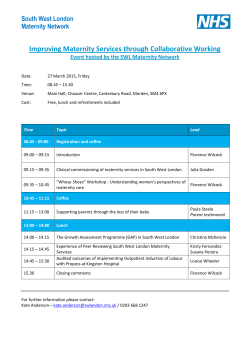

Queer challenges in maternity care - Bora