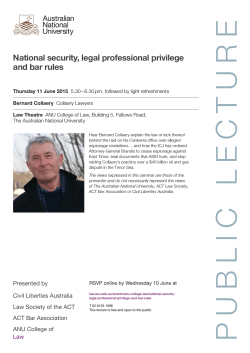

Essays, opinions and ideas on public policy