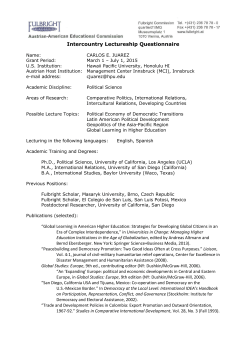

THE CAPITALIST SYSTEM AND REPRESENTATIVE