Document 17355

Angiotensin-Converting

Peter

G. Pryde,

P.G

Pryde,

Aileen

CE.

B. Sedman,2

Nugent,

M.

Obstetrics/Gynecology,

cal

Center,

A.B.

M.

M.

Soc,

Jr.,

E. Nugent,

Department

of

Michigan

of

Medical

Center,

of

Pathology,

Center.

Nephrol.

of

Jr. , Department

Barr,

Medical

Clark

Medi-

Ml

Jr. , Department

Barr,

(J. Am.

Arbor,

of Michigan

Michigan

Barr,

University

Ann

Sedman,

University

Enzyme

Ann Arbor,

1993;

Pediatrics,

Ann Arbor,

University

Ml

of

Ml

3:1575-1582)

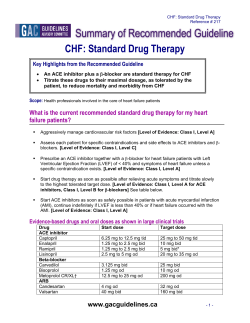

ABSTRACT

Angiotensin-converting

enzyme

(ACE)

inhibitors

are

widely used for controlling

hypertension.

Their use in

women

who are pregnant

is not without

risk to the

fetus. We describe

three infants exposed

in utero to

ACE inhibitors

who had adverse

outcomes.

These

cases, combined

with other reports in the literature,

suggest

strongly

that these drugs are fetotoxic.

ACE

inhibitor

fetopathy

is characterized

by fetal hypotension,

anuria-oligohydramnios,

monary

hypoplasia,

pocalvaria.

Although

fetal effects

has yet

the debilitating

and

age when it occurs,

ACE inhibitors

not be

in the

second

Key Words:

and

Kidney,

oligohydramnios,

growth

restriction,

pul-

renal tubular dysplasia,

and hythe true frequency

of adverse

to be determined,

because

of

lethal nature

of the fetal damit is our recommendation

that

used in pregnancy,

particularly

third

trimesters.

captopril,

teratogen,

enalapril,

lisinopril,

skull, anuria.

fetotoxin

I

n the decade

since

their introduction,

the angiotensin-converting

enzyme

(ACE)

inhibitors

have

gained

widespread

acceptance

in the management

of

hypertension.

Their

success

(even

as monotherapy)

and relative

paucity

of side effects

have

contributed

to this popularity

(1 -3). Further,

the lack of metabolic

changes

(such

as hyperglycemia

or hyperbipidemla).

as well as a possible

ameliorating

effect

on the progression

of diabetic

nephropathy,

has prompted

the

suggestion

that

ACE inhibitors

be considered

first-

‘Received

August

2Correspondence

0297,

University

25, 1992. Accepted

to Dr. A. B. Sedman,

of Michigan

Medical

November

Pediatric

Center.

30. 1992.

Nephrology,

Ann Arbor,

1046-6673/0309-1575$03.00/0

Journal

of the American

society

of Nephrology

Copyright

© 1993 by the American

Society

of Nephrology

Journal

of the

American

Society

of Nephrology

Room

L2602,

MI 48 109-0297.

Box

Inhibitor

and

Mason

Barr,

Fetopathy’

Jr.

line agents

in the management

of hypertensive

diabetics

(1.3.4).

As early

as 1 980,

there

were

worrisome

reports

of

extraordinary

fetal

loss rates

in a variety

of experimental

animals

exposed

to ACE

inhibitors

during

gestation

(5-7).

In 1 98 1 the first

case

of adverse

fetal outcome

in a human

pregnancy

exposed

to captopril

was reported

(8). Soon,

other

cases

appeared

Implicating

both

captopril

and enalaprib

as possible

fetotoxins

(9-12).

The animal

data,

coupled

with

a

growing

list of adverse

human

pregnancy

outcomes,

prompted

warnings

as early

as 1 985 against

the use

of ACE inhibitors

during

human

gestation

( 1 3). However,

in contacts

with

prescribing

physicians,

our

experience

has been

that many

are not aware

of the

potential

danger

to the fetus

from

ACE inhibitor

exposure.

We report

three

cases

from

our institution

of adverse

fetal

outcome

in hypertensive

pregnancies

exposed

to ACE inhibitors,

and we review

previously

reported

cases

(8-12,14-24).

Further,

we propose

that

sufficient

evidence

exists

to implicate

the ACE

inhibitors

as fetotoxins

and suggest

the designation

“ACE inhibitor

fetopathy.”

,

CASE

Patient

REPORTS

I

The mother

was a 26-yr-old.

gravida

2, para 0. with

an 8-yr history

of systemic

bupus erythematosus.

Her

associated

hypertension

was controlled

by a regimen

of prednisone.

5 to 1 0 mg/day,

atenobol,

1 00 mg/day,

furosemide,

20 mg/day,

and captopril,

1 50 mg/day.

Ultrasonographic

evaluation

at 1 9 wk of gestation

revealed

oligohydramnios

but no fetal structural

abnormalities.

Over the next several

weeks,

there

was

persistence

of the oligohydramnios

and evolution

of

mild growth

restriction.

At 33 wk of gestation.

labor

was induced

because

of a worsening

biophysical

profile. A 1 .440-g

female

was delivered

vaginally

from a

breech

presentation.

Apgar

scores

were

1 and 5 at 1

and 5 mm,

respectively.

Despite

maximal

ventilator

support.

the infant

remained

hypoxic

and

became

progressively

acidotic.

Her hypotenslon

was

unresponsive

to volume

and pressor

therapy,

and during

the 14 h before

death,

there

was no urine

output.

At autopsy,

the hand,

foot, and face deformational

features

of the oligohydramnios

sequence

were identified.

The lungs

were

small

with

histologic

features

of pulmonary

hypoplasia.

A calcified

thrombus

in the

subhepatic

vena

cava

extended

into the renal

veins

bilaterally.

Subdiaphragmatic

venous

return

to the

1575

ACE Inhibitor

Fetopathy

heart

was via a well-developed,

thick-walled

azygous

system

to the superior

vena

cava.

The kidneys

were

enlarged

compared

with

gestationab

age-matched

controls

and had histologic

changes

consistent

with

renal

tubular

dysplasia.

The distal

urinary

tract,

although

slender

and empty.

was structurally

normal

and patent.

The brain

and cranial

base were normal.

However,

the calvarial bones, although

normal

in

shape

and

configuration,

were

remarkably

small,

leaving the top third

of the brain

unprotected

by bone

(Figure 1). Microscopically,

these

bones

were

thin

with poor trabeculatlon

and

marrow

development

compared

with

those

of age-matched

controls

(see

reference

38).

Patient

2

The mother

was an 18-yr-old

primigravida

with

renovascular

hypertension

of 10 yr duration.

She had

been managed

on multiagent

therapy with variable

success

until

age 18, at which

time llsinoprib

monotherapy

was initiated

with

the establishment

of excellent

control.

When

she became

pregnant,

lisinopril

was continued.

At 16 wk of gestation,

an ultrasound

examination

revealed

a fetus

of appropriate

size with

a normal

anatomic

survey

and normal

amniotic

fluid

volume.

Subsequently,

there

was

no suspicion

of

problems

until

the onset

of labor

at 32 wk of gestation.

After

a failed

trial of tocolysis,

a 1 .480-g

male

was

delivered

by cesarean

section.

Amniotic

fluid

volume

was not described.

Apgar

scores

were

4 and

7 at 1 and 5 mm,

respectively.

The infant

required

48 h of mechanical

ventilation

for respiratory

distress.

The newborn

period

was complicated

by hypotension and anuria

that

failed

to respond

to fluid chablenge

and

pressor

support.

Ultrasound

evaluation

showed

normal

size and appearance

of the kidneys

and

renal

collecting

system.

Renal

artery

Doppler

studies

demonstrated

bilateral

flow.

At 8 days

of age, the infant

remained

anuric

and

peritoneab dialysis was initiated. By day 12 of life, he

began

to pass

small

amounts

of urine. ACE activity

increased

from a day 12 value

of 7.9 U/mL

(normal,

20 to 50) to 22 U/mL

on day 37. A kidney

biopsy

performed

at 4 wk of age demonstrated

evidence

of

previous

ATN,

patchy

cortical

necrosis,

and lack of

Figure 1. Hypocalvaria

(Patient

1). The skull viewed from above,

with the fibrous tissue of the fontanels

to emphasize

the diminutive

size of the bones. Reprinted

with permission

from Barr and Cohen (38).

1576

Volume

and sutures

3.

Number

removed

9

1993

Pryde

Patient

differentiation

of the proximal

convoluted

tubules

(Figure

2). Although

his urine

volume

increased

modestby over the next

several

weeks,

he remained

dependent

on peritoneal

dialysis

and,

at 22 months

of

age. received

a successful

kidney

transplant.

He mitialby suffered

from intestinal

malabsorption

and Severe

growth

retardation.

After

the transplant.

his

growth

remains

delayed.

but his cognitive

function

is progressing

normally.

At birth,

his fontanels

were

noted

to be barge and

the sutures

excessively

wide.

At 1 month

of age, the

cabvarlal

plates

were

small

but of appropriate

shape

and position.

The width

of the sagittal.

coronal,

and

lambdoidab

sutures

measured

3, 3, and 2 cm, respectively.

The anterior

fontaneb

was 6 cm long by 4 cm

wide,

and the posterior

fontanel

was 4 cm by 4 cm.

Subsequently,

considerable

growth

of the skull bones

was noted

so that

by 3 months

of age. the sutures

had narrowed

to 0.5 cm in width,

with a corresponding reduction

in size of the fontanebs.

At 22 months

of age, his anterior

fontanel

was still patent,

but the

rest of the skull

examination

was unremarkable.

Figure 2. ACE inhibitor-exposed

kidney (Patient 2) showing

of differentiation

between

proximal

and distal convoluted

original magnification,

x20.

Journal

of the

American

Society

of Nephrology

et al

3

The mother

was a 30-yr-old

primigravida

with a 9yr history

of presumed

essential

hypertension

adequately

controlled

by atenobob

until

several

months

before

conception.

At that

time,

she was

changed

electively

to enalapril,

5 mg/day.

Her blood

pressure

was well controlled

until

20 wk of gestation,

when

the daily dose was increased

to 7.5 mg for an elevated

diastolic

pressure.

At 30 wk. fundal

height

was noted

to be subnormal

and ultrasonography

demonstrated

fetal

growth

restriction

and profound

oligohydramnios.

At 32 wk,

a contraction

stress

test

showed

recurrent

decelerations

and the infant

was delivered

by cesarean

section.

The boy infant weighed

only 980 g although

the

physical examination

was appropriate

for 32 wk of

gestation. Apgar scores were 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 mm,

respectively, but mild grunting

progressed

to frank

respiratory

distress

and

by 2 h of age mechanical

ventilation was required. He was

profoundly

hypotensive

(mean

arterial

pressure

of 16 mm Hg) and

remained

so despite administration

of dopammne,

do-

dilated

tubules,

Bowman’s

spaces and tubules,

and increased

mesenchyme.

old tubular necrosis, lack

Periodic

acid-Schiff

stain;

1577

ACE Inhibitor

Fetopathy

butamine,

and

epmnephrmne

and

aggressive

hydration.

Hypotension

and anuria

persisted

until

initiation,

on day 5 of life, of peritoneal

dialysis.

After

14

h of dialysis.

his blood pressure

rose to 40/ 1 7 mm Hg

and

7 mL of urine

was

obtained.

On day

8, the

dialysate

became

cloudy

and

bowel

obstruction

or

perforation

was suspected.

At laparotomy,

a length

of ischemic

jejunum

was

resected.

Postoperatively,

he remained

hypotensive

despite

massive

pressor

support

and died on day 9.

At autopsy,

he had barge fontanebs

(anterior,

5.0 x

3.5 cm: posterior,

2.0 x 1 .5 cm) and widened

sutures

(sagittal.

1 cm; coronals

and

bambdoidabs,

0.3 cm:

metopic,

0.5 cm). His face was wide with a short

nose

and anteverted

nares.

His arms

(150

mm) and begs

(120 mm) were

short

in relation

to his crown-rump

length

(285 mm).

The kidneys

were

barge (combined

weight.

16.1 g; expected,

9.0 ± 1.6 for body weight).

but no other

gross

abnormalities

of the urinary

tract

or renal

vascular

system

were

found.

Microscopic

examinations

of the kidneys

showed

tubular

dysplasia (Figure

3). The lungs,

particularly

the left one,

were small

(right,

13.7 g; left, 6.9 g; combined

weight,

20.6 g; expected,

scopicab

features

25.4 ± 5.2)

of hypoplasia.

and

showed

the

micro-

DISCUSSION

The ACE inhibitors

are competitive

inhibitors

of

kininase

II. Their

complex

pharmacology

has been

reviewed

in detail

by others

( 1 -3). Most importantly.

they

affect

both

the renin-angiotensin-abdosterone

and

the

bradykinin-prostaglandin

systems.

Many

other

antlhypertensive

agents

tend

to increase

peripherab

resistance

and affect

the metabolism

of glucose, lipids,

and electrolytes.

In contrast,

ACE inhibitors

decrease

vascular

resistance

and

have

no

known

adverse

metabolic

consequences

( 1 ,3). In the

absence

of heart

failure,

they

produce

little

change

in heart

rate,

cardiac

output,

or pulmonary

wedge

pressure

(25-27).

An important

effect

of ACE inhibitors

is on the renal

microvasculature,

resulting

in

dilatation

of the gbomerular

efferent

arterioles

and a

decrease

in filtration

pressure.

Excretion

of the ACE inhibitors

is principally

by

the kidney. They are also known

to cross the human

(

,

‘:N.l

..

a

?

-,

,4

_J

a

.

-

-

4

:“

Figure 3. ACE Inhibitor-exposed

kidney

tubules, dilated

tubules, and increased

1578

4

(Patient 3) showing tubular dysplasia:

minimal differentiation

of proximal

mesenchyme.

Periodic acid-Schiff

stain; original magnification,

x20.

Volume

3’

Number

convoluted

9’

1993

Pryde

TABLE

1. Cases

of pregnancy

outcome

Author,

(Ref. No.),

Year

Guignard

1981

Dummy

(9),

Boutroy

Burger

Renovascular

pertension

(10),

1984

Caraman

eta!. (11).

1984

Caraman

eta!.

(11).

1984

Rothberg

and Iorenz

(12), 1984

Fiocchi eta!. (14),

1984

eta!.

(15),

1985

Schubiger

29 wk; cesarean

I 0%

2nd trimester

hy-

eta!.

(16)

Broughton-Pipkmn

a!. (17), 1989

et

Mehta

3-10%

34 wk; cesarean

10-50%

28 wk; cesarean

etiology

section;

No

No

RDS, PDA, survived

section;

No

No

RDS, PDA, survived

section;

Yes

Yes

section

Yes

Yes

Hypocalvaria,

dialysis,

death day 30

Survived

section;

No

No

IUGR, survived

section;

Yes

Yes

section;

Yes

Yes

Decreased

ACE activity, dialysis, survived

Placental

abruption,

severe RDS, death

day 6

IUFD, suspected

renal

tubular dysgenesis

Hypoplastic

lungs, hypocalvaria,

death

day 10

RDS, death day 7

N/A

Yes

Yes

Implied

Yes

Yes

Yes

Systemic

lupus

thematosus

Systemic lupus

thematosus

transplant

(21),

IUFD, intrauterine

patent

ductus

fetal

eryery-

death:

arteriosus;

26 wk; cesarean

section;

3%

34 wk; cesarean

section;

weight not recorded

lUG?, intrauterine

N/A,

not

growth

of the American

Society

of Nephrology

restriction;

RDS. respiratory

Hypoplastic

lungs,

renal tubular dysgenesis

distress syndrome;

PIH, pregnancy-induced

applicable.

placenta.

In the

fetus,

it Is presumed

that

these

agents

are, at beast in part,

also renally

excreted

into

the amniotic

fluid and recycled

by fetal swallowing.

In animal

studies,

the administration

of captopril

in doses

comparable

to those

used In human

therapy

has

been

associated

with

significant

rates

of fetal

loss.

Chronically

cannulated

pregnant

ewes

given

3

mg/kg

of captopril

demonstrated

fetal

loss rates

in

excess

of 80% (7). The administration

of 2.5 to 5.0

mg/kg

of captopril

per day to pregnant

rabbits

yielded

pregnancy

loss rates

ranging

from

37 to 92% (5-7).

Severe

and

prolonged

fetal

hypotension

has

been

demonstrated

in the sheep

model

(7) and

has been

implicated

in the high rate of fetal wastage.

Possible

impairment

of uteroplacental

perfusion

by ACE inhibitors

has also been

suggested

(6,7).

Journal

Yes

Yes

(20),

1989

PDA.

Yes

section:

vaginal

delivery

32 wk; cesarean

section;

3-10%

Scott and Purohit

Abbreviations:

N/A

29 wk IUFD, spontaneous

Renal

hypertension;

N/A

Pulmonary

hypoplasia,

decreased

ACE activity, death day 8

Elective abortion,

hypocalvaria,

transverse limb defect

PDA-surgical

repair,

Renal transplant

(19),

Other

and Anuria

survived

34 wk; cesarean

1989

0

Neonatal

Hypotension

3-10%

PIH

and Modi

or in pairs’

Yes

termination

34 wk; cesarean

310%

34 wk; cesarean

<3%

35 wk; cesarean

10-50%

36 wk; cesarean

1989

Cunniff eta!.

1990

Oligohydramnios

individually

<3%

eta!.

(18),

reported

Yes

<3%

Renovascular

hypertension

Essential hypertension

Essential hypertension

Unclear

section;

34 wk; cesarean

Nephrotic

Syndrome

Renovascular

hypertension

Glomerulonephritis,

1988

Knott

exposure

Birth Weight

hypertension

Ducret

inhibitor

(Percentile)

Preeclampsia

eta!.

ACE

Gestation;

Mode of Delivery;

Maternal

Disease

eta!. (8),

and

1981

after

et al

The true

rates

of adverse

fetal

effects

from

ACE

inhibitor

use in human

pregnancy

cannot

be determined

from available

information.

Certainly,

a number of exposed

pregnancies

have

resulted

in no discernible

adverse

effect.

In the largest

published

series,

there

were

3 1 pregnancies

exposed

either

to

captoprib

(N = 22) or enabapril

(N = 9) (23).

The

reported

adverse

fetal

outcomes

included

nine

cases

of intrauterine

growth

restriction,

three

intrauterine

deaths,

and two infants

with

patent

ductus

arteriosus. The other

cases

in this report

were

presumably

unaffected.

However,

the list of case reports

suggesting adverse

ACE

inhibitor-related

fetal

outcome

continues

to grow

and a consistent

pattern

of manifestations

has

emerged.

We have

compiled

the reported

cases

of ACE inhibitor

use in pregnancy:

Table

1579

ACE Inhibitor

Fetopathy

TABLE 2. Case

series

.-o;-’-.-

,.....

reporting

Author

(Ref. No.),

Year

pregnancy

No. of

Cases

in Series

Plouin and Tchobroutsky (22), 1985

7 cases

not report-

..‘.

outcomes

IUGR

2/7 <3%

after

ACE inhibitor

exposurea

Oh

h

dramnios

Neonatal

Hypotension

and Anuria

-

2/7 Yes

None

noted

ed elsewhere

Other

2/7 Spontaneous

abortion

1/7 IUFD

4/7 survived

2/7 PDA

Kreft-Jais

1988

et a!. (23),

31 cases not

reported

9/31 <3%

Not recorded

Not recorded

elsewhere

Rose et a!. (24),

4 cases not reported elsewhere

1989

#{176}Abbrevlatlons as

in

footnote

I PDA surgery

Weights not 2/4 Yes

recorded

2/4 not recorded

1580

4/4 Yes

2 Full recovery

2 renal insufficiency

4 survivors

to Table 1.

1 summarizes

single

case reports

(8- 1 2. 1 4-2 1 ). and

Table

2 summarizes

case series

(22-24).

Cases

that

were

reported

alone

(in Table

1 ). but that

were

also

included

in a case series,

were

excluded

from

Table

2.

The

most

commonly

reported

adverse

effects

in

ACE

inhibitor-exposed

pregnancies

are middleto

late-trimester

onset

of oligohydramnios

and

intrauterine

growth

restriction,

followed

by delivery

of an

infant

whose

course

is complicated

by prolonged

and

often

severe

hypotenslon

and anuria.

This sequence

was observed

in our 3 cases

as well as in 1 3 prevlously

reported

cases

(Tables

1 and 2). Our first case

and three

previously

reported

cases

(8, 1 9,2 1 ) had the

morphologic

findings

of the oligohydramnios

deformation

sequence,

including

the

neonatally

lethal

component,

pulmonary

hypoplasia.

In each

of our cases,

the immediate

postpartum

period

was complicated

by profound

hypotenslon

and

anuria.

As observed

in 1 3 previous

cases

manifesting

this complication,

the hypotension

was recalcitrant

to both

volume

and pressor

support

therapy.

In Patient

1 death

of the neonate

occurred

before

normotension

could

be established.

In Patients

2 and 3, the

infants

remained

profoundly

hypotensive

and anuric

until

dialysis

was initiated

several

days

after

birth.

However,

the combination

of severe

hypotension

and

anuria

in a premature

and/or

growth-retarded

infant

makes

both peritoneal

dialysis

and hemodialysis

extremeby

difficult,

and the mortality

rate is exceptionally high.

Each

of our patients

had renal

tubular

dysplasia.

Identical

kidney

lesions

have

been

reported

in one

other

case

of neonatal

renal

failure

(2 1 ) and

suspected

in another

(1 8) in which

transplacental

ACE

inhibitors

were

implicated.

Renal

tubular

dysplasia

is characterized

by dilation

of Bowman’s

spaces

and

tubules,

diminished

to absent

differentiation

of prox,

1/7 PDA/surgery

3 Stillborn

2 PDA

imal convoluted

tubules

and

increased

cortical

and

medublary

mesenchyme

(and later fibrosis).

The histologic

changes

in the kidney

are compatible

with

ischemic

injury,

having

the added

component

of deficient

tubular

differentiation.

Renal

tubular

dysplasia is also found

in fetuses

unexposed

to ACE inhibitors but who have

presumably

been

hypotensive

tn

utero

(e.g. . the donor

twin

in the twin-twin

transfusion syndrome)

(28). Although

a histologically

similar

renal

lesion

has been

described

in a rare autosomab

recessive

disorder

(29,30),

the clinical

course

and

histories

of our cases

and those

previously

described

suggest

a related

but etiobogically

distinct

lesion.

The

kidneys

in two of our patients

were

large.

a finding

first noted

by Cunniff

et at. (2 1 ). Nephromegaly

has

also been

noted

as one of the features

of the hereditary form of renal

tubular

dysplasia

(29,30).

Oligohydramnios,

intrauterine

growth

restriction,

and fetal

distress

are not uncommon

complications

of hypertensive

pregnancies.

However,

the finding

of

evolving

oligohydramnios

followed

by the delivery

of

a neonate

with

prolonged

hypotension

and

anuria

has not been

included

in the well-described

list of

complications

of maternal

hypertension

and its tradltional

therapy.

In this setting.

the probability

that

the observed

oligohydramnios

was

in fact

due

to

drug-related

fetal hypotension

and renal

failure

that

persisted

into the neonatal

period

needs

to be serlously considered.

Evidence

in support

of this hypothesis is the reported

occurrence

of profound

hypotension, anuria,

and low ACE activity

in neonates

given

low doses

of ACE

inhibitors

for the treatment

of

hypertension

(3 1 -33).

Similarly

blunted

ACE activity

was observed

in our second

patient.

Additional

evidence

Includes

reported

observations

that

the onset

of oligohydramnios

is temporally

related

to the initiation

of ACE inhibitor

therapy

(8. 1 6). In one case,

the amniotic

fluid

volume

was

observed

to return

Volume

3

‘

Number

9

‘

1993

Pryde

toward

normal

after

the drug was discontinued;

however, that

infant

died of respiratory

insufficiency

on

day 6 of life (17).

It has been emphasized

that the renin-angiotensin

system

becomes

crucially

Important

under

conditions

of low renal

perfusion

pressure

(34,35).

In this

setting,

angiotensin

Il-mediated

efferent

arteriolar

resistance

becomes

essential

to the maintenance

of

gbomerular

filtration

and

the production

of urine.

Under

normal

circumstances,

the fetus

and

early

neonate

have a low renal

perfusion

pressure

(36,37).

Therefore,

it makes

good biologic

sense

to postulate

that transplacental

administration

of ACE inhibitors

would

cause

decreased

angiotension

II levels

in the

fetus,

which

would

have the dual effect

of a further

decrement

in systemic

blood

pressure

as well as the

loss

of compensatory

efferent

arteriolar

tone.

The

result

would

be a marked

decrease

in gbomerular

filtration

pressure

with

the attendant

loss of urine

production,

manifest

as oligohydramnios.

Apart

from the renal

failure

and related

abnormalities

discussed

above,

our patients

and three

previously

reported

patients

(1 2, 1 9) had hypoplasia

of the

membranous

bones

of the

skull,

or hypocalvaria.

This created

symmetrically

enlarged

sutures

and fontanels

and, in severe

cases,

left the brain

essentially

unprotected

by skull

and potentially

liable

to trauma

during

labor

and delivery.

Although

there

are now

only a total

of six cases

In which

this skull

lesion

is

described,

we believe

it may

be more

common

but

unrecognized

by physicians

not alerted

to the phenomenon

and therefore

not looking

for it. The possible pathogenesis

of hypocalvaria

is considered

in

more

detail

by Barr and Cohen

(38).

Occasionally,

there

is a drug whose

record

in pregnancy

is so frequently

associated

with

adverse

outcome

of so specific

a pattern

that

it becomes

clear

that

its use must

be restricted

before

proof

of harm

can be obtained

by epidemiologic

studies.

We believe

this to be the case with the drug class

of ACE inhibitors.

There

are two mammalian

models

suggesting

substantial

fetotoxicity

in a dose-related

fashion.

There

Is a strong

and consistent

pattern

to the reported

human

cases

of ACE Inhibitor-related

adverse

outcomes:

the syndrome

of oligohydramnios-anuria.

neonatal

hypotension,

renal

tubular

dysplasia,

and

hypocalvarla

is too specific

In association

with

the

use of these

drugs

to be ignored.

There

is a plausible

biologic

mechanism

to explain

the relationship:

the

features

of ACE Inhibitor

fetopathy

suggest

that

the

underlying

pathogenetic

mechanism

Is fetal hypotension,

but clearly

more

research

in animal

models

is

warranted

to clarify

the pathophysiology

of the toxic

effect.

Although

all of the features

of the fetopathy

may

not be specific

to ACE inhibitors,

we suggest

that ACE Inhibitors

are particularly

liable

to produce

these

fetal

renal

effects

(with

their

sequels

anuria-

Journal

of the

American

Society

of Nephrology

et al

oligohydramnios.

pulmonary

hypoplasia,

growth

restriction)

and hypocalvaria.

We suggest

that this syndrome

be labeled

“ACE inhibitor

fetopathy”

and recommend

restrictions

on the use of these

drugs

in

pregnancy.

RECOMMENDATIONS

We have

deliberately

used

the word

“fetopathy”

rather

than

“teratogenlcity”

In this discussion

of ACE

Inhibitor-rebated

adverse

outcomes.

To date,

there

is

no convincing

evidence

of a true teratogenic

or firsttrimester

effect

of ACE

inhibitors

on the

human

embryo.

and exposure

during

this

time

is not construed

as an indication

for abortion.

In contrast,

secondand third-trimester

exposure

seems

to carry

an Important.

but as yet unquantified.

risk of fetotoxicity,

resulting

in major

morbidity

and mortality.

Emphasis

on this distinction

is important

because

of

the indisputable

therapeutic

usefulness

of the drugs

of this

class

and

the potentiality

that

women

will

conceive

while

taking

one of them.

Hanssens

et at.

(39) suggest

that

enalapril

may be the more

toxic

of

the clinically

available

ACE inhibitors.

Be that

as it

may,

fetotoxiclty

has been

observed

In association

with captopril

and lisinopril,

as well as enalapril.

and

there

is no reason

to assume

that any ACE Inhibitor

will be really

safe for the fetus.

Women

of reproductive

age who can clearly

benefit

from these

drugs

should

be advised

of the hazards

to

the fetus,

educated

about

the Importance

of periconceptionab

antihypertenslon

regimen

change.

and

counseled

about

the use of safe and reliable

contraception.

With

other

safer

antihypertensive

agents

available,

we feel there

is no justification

for ACE

inhibitor

use once pregnancy

has been documented.

REFERENCES

1 . Williams

GH: Converting

enzyme

inhibitors

in

the treatment

of hypertension.

N Engb J Med

1988:319:1517-1524.

2. Rotmensch

ff1, Viasses

PH, Ferguson

RK: Angiotensin-converting

enzyme

inhibitors.

Med

Clin North

Am 1988:72:399-425.

3. Gavras

H: The place

of angiotensmn

converting

enzyme

inhibitors

In the treatment

of cardlovascular

diseases.

N Engl

J Med

1988:3

19:

1 54 1 -1543.

4. Taguma

Y, Kitamoto

Y, Futaki

G, et at.: Effect

of captopril

on heavy

protelnuria

In azotemic

diabetics. N Engl J Med 1985;313:1617-1620.

5. Broughton-Pipkin

F, Turner

SR. Symonds

EM:

Possible

risk

with

captoprib

during

pregnancy.

Some

animal

data.

Lancet

1 980:2:

[256.

6. Ferris

TF, Weir

EK: Effect

of captoprib

on uterme blood flow and prostaglandmn

E synthesis

in

the

pregnant

rabbit.

J Clin

Invest

1982:71:

809-815.

7. Broughton-Pipkin

F, Symonds

EM, Turner

SR:

The effect

of captopril

(SQ 14,225)

upon

mother

1581

ACE Inhibitor

8.

9.

1 0.

1 1.

1 2.

1 3.

1 4.

1 5.

1 6.

1 7.

1 8.

1 9.

20.

21.

22.

23.

1582

Fetopathy

and fetus

in the chronically

cannubated

ewe and

in the

pregnant

rabbit.

J Physiol

1982:323:

415-422.

Guignard

JP, Burgener

F, Calaine

A: Persistent

anuria

in a neonate:

a side effect

of captopril?

Int J Pediatr

Nephrol

1981:2:133.

Dummy

PC, Burger

P du T: Fetal

abnormality

associated

with the use of captoprib

during

pregnancy. S Afr Med J 1981:60:805.

Boutroy

MJ, Vent

P. Hunault

de Ligny

B, Milton

A: Captopril

administration

in pregnancy

impairs

fetal angiotensmn

converting

enzyme

activity

and neonatal

adaptation.

Lancet

1984:2:

935-936.

Caraman

PL, Milton

A, Hunault

de Ligny

B, et

at. : Grossesses

sous

captopril.

Therapie

1984:

39:59-62.

Rothberg

AD. Lorenz

R: Can

captopril

cause

fetal

and neonatal

renal

failure?

Pediatr

Pharmacol 1 984;4: 189-192.

Lindheimer

MD, Katz

A!: Hypertension

in pre

nancy

(current

concepts).

N Engb J Med

1 98

313:675-680.

Fiocchi

R, Ligney

P. Fagard

R, Staessen

J.

Amery

A: Captopril

during

pregnancy.

Lancet

1984:2:1153.

Ducret

F, Pointet

PH, Laurengeon

B, Jacoulet

C, Gagnaire

J: Grossesse

sous inhibiteur

de l’enzyme de conversion.

Presse

Med 1 985; 14:897.

Schubiger

G, Flury

G, Nussberger

J: Enalapril

for

pregnancy-induced

hypertension

:

Acute

renal

failure

in the neonate.

Ann

Intern

Med

1988:108:215-216.

Broughton-Pipkin

F, Baker

PN, Symonds

EM:

Angiotensmn

converting

enzyme

inhibitors

in

pregnancy.

Lancet

1989:2:96-97.

Knott

PD, Thorpe

SS, Lamont

CAR: Congenital

renal

dysgenesis

possibly

due to captoprib.

Lancet 1989:1:451.

Mehta

N, Modi N: ACE inhibitors

in pregnancy.

Lancet

1989:2:96.

Scott

AA, Purohit

DM: Neonatal

renal

failure:

A

complication

of maternal

antihypertensive

therapy.

Am

J Obstet

Gynecol

1989:160:

12231224.

Cunniff

C, Jones

KL, Phillipson

K, Short

S.

Wujek

J: Oligohydramnios

and renal tubular

malformation

associated

with maternal

enalapril

use.

Am

J Obstet

Gynecol

1990:162:

187-189.

Plouin

PF, Tchobroutsky

C: Inhibition

de b’enzyme

de conversion

de 1 angiotensine

au cours

de la grossesse

humaine.

Qumnze cas. Presse

Med

1985:14:2175-2178.

Kreft-Jais

C, Plouin

C, Tchobroutsky

C, Boutroy MJ: Angiotensmn-converting

enzyme

inhib-

-

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

3 1.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

itors during

pregnancy:

A survey

of 22 patients

given

captopril

and

nine

given

enabaprib.

Br J

Obstet

Gynaecol

1988:95:420-422.

Rosa

FW, Bosco

LA, Fossum-Graham

C, Mustien

JB, Dreis

M, Creamer

J: Neonatal

anuria

with

maternal

angiotensin-converting

enzyme

inhibition.

Obstet

Gynecob

1989:74:371-374.

Vidt DG, Bravo

EL, Fouad

FM: Captopril.

N Engb

J Med 1982:306:214-2

19.

Todd

PA, Heel

RC: Enalapril:

A review

of its

pharmacodynamic

properties.

and

therapeutic

use in hypertension

and congestive

heart

failure.

Drugs l986;3l:198-248.

Gomez

HJ, Cirillo

VJ, Moncloa

F: The clinical

pharmacology

of bisinoprib.

J Cardiovasc

Pharmacol

1987:9(Suppb

3):S27-S34.

Martin

PA, Jones

KL, Mendoza

A, Barr

M, Benirschke

K: The effect

of ACE inhibition

on the

fetal

kidney:

Decreased

renal

blood

flow.

Teratology 1993:46:317-321.

Ailanson

JE, Pantzar

JT, MacLeod

PM: Possible new autosomab

recessive

syndrome

with unusual

renal

histopathobogicab

changes.

Am J Med

Genet

1 983; 16:57-60.

Bernstein

J: Renal

tubular

dysgenesis.

Pediatr

Pathol

1988:8:453-456.

Tack

ED, Perlman

JM:

Renal

failure

in sick

hypertensive

premature

infants

receiving

captopril

therapy.

J Pediatr

1988:1

12:805-8

10.

Penman

JM,

Volpe

JJ:

Neurobogic

complications

of captoprib

treatment

of neonatal

hypertension.

Pediatrics

1989:83:47-52.

Wells

TG, Bunclunan

TE, Kearns

GL: Treatment

of neonatal

hypertension

with enabapril.

J

Pediatr

1990:117:664-667.

Hall JE, Guyton

AC, Jackson

TE, Coleman

TG,

Lohmeier

TE, Tnppodo

NC: Control

of gbomerular filtration

rate by renmn-angiotensin

system.

Am J Physiol 1977;233:F366-372.

Blythe

WB: Captoprib

and renal

autoregubation.

N Enl

J Med 1983:308:390-391.

Rudolph

AM, Heyman

MA, Teramo

KAW,

Barrett CT, Raffia

NCR: Study

on the circulation

of

the previable

human

fetus.

Pediatr

Res 1971:5:

452-465.

Guignard

JP:

Renal

function

in the newborn

infant.

Pediatr

Clin

North

Am

1982:9:

777-790.

Barr M, Cohen

MM: ACE inhibitor

fetopathy

and

hypocalvaria:

The kidney-skull

connection.

Teratology 1991:44:485-495.

Hanssens

M, Keurse

MJNC,

Vankelecom

F, Van

Assch

FA: Fetal

and neonatal

effects of treatment

with

angiotensin-converting

enzyme

inhibitors

in pregnancy.

Obstet

Gynecol

1991:78:

128-135.

Volume

3’

Number

9

1993

© Copyright 2026