Document 175594

~tl I

)

)

Past and Present Members

Mr EAdcock

Mr N Apsey

MrE Bacon

Mr A J C Badger

Mr R Barnett

Mr W Barnett

Mr DE Bathe

Mr CT Beabey

Miss J Bennett

Mr R D Broad wood

MrE LClarke

Mr L Clayton

MrFW Codd

MrE Cogans

MrG A Cooper

MrW HCooper

Mr H Copestake

Mr H Cridge

Mr W Darbey

Mr C Dashwood

Mrs M Foreman

MrC Galley

MrRWGates

Mr A Giddings

Mr A Goddard

Mr DGould

Mr J Greenaway

MrP J Harper

Dr J C Harrison

Mr D Heasman .

MrDHebbs

MrG Hewitt

MrE Hickson

MtJ Holgate

Mr C Hutchins

Mr J Irvin

MrFJackman

Mr RJesson

Mr RJones

MrD Josey

Mr J Kellet

Mr A Kimber

MrT King

MrS Marks

MrDMartin

MrD Meeks

Mr P Miller

MrDMoon

MrDMorgan

MrS Muir

MrDNewton

MrWNewsom

Mr J Porter

Mr A Ridgway

Mr K Rig lin

Mr L Rowlands

Mr G Scarlett

Mr J Sogings

Mr C Shearing

MrHGSladc

Mr A Smalley

Mr PTyson

MrVWaters

Mr D Wilson

Old British Beers

and

How To Make Them

'

l

Second Edition

Dr John Harrison

and Members of

The Durden Park Beer Circle

GREAT FERMENTATIONS

OF SANTA ROSA

840 Piner Road #14

Santa Rosa, CA 95403

{707) 544-2520

{)

.~~r;

)

~

~

Preface

1

'

This booklet is an expanded edition of our publication entitled

Old British Beers and How to Make Them, published in 1976. It

contains instructions for brewing sixty British Beers ranging

from pre-1400 unhopped ales to early 1900s oatmeal stouts.

It is not intended to be a definitive history of the brewing

industry, brewing materials or brewing practices. These topics

are mentioned only where they have a significant impact on

ale formulations, e.g. the British Patent by D. Wheeler in 1817

for the drum-roasting of black malt and roast barley. This led

within a few years to the wholesale re-formulation of porters

and stouts.

Copyright© 1991, The Durden Park Beer Circle

All rights reserved

Acknowledgements

First published 1976

Revised 1991

The Durden Park Beer Circle would like to thank the Trustees

of the Scottish Brewing Archive for permission to use material

held in the archive at Herriot-Watt University, Edinburgh.

Also gratefully acknowledged is the considerable assistance

given by Archivist, Charles McMaster BA, in extracting useful

information.

The circle would also like to thank Whitbread plc for

information on their Victorian porter, double stout and triple

stout; and Courage plc for permission to publish the recipe for

Simond's 1880 Bitter extracted from their Brewing Archive at

Bristol.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Harrison, John

Old British beers and how to make them.

I. Title

641.23

ISBN

0 9517752 0 0

Typeset at The University of London Computer Centre

4

f

)

Contents

Introduction ................................................................................... vii

Part 1. Historical Notes ................................................................ 1

General ..................................................................................... 1

Nomenclature .......................................................................... 1

Weights and Measures ........................................................... 2

Brewing Methods (Old versus Present-Day) ...................... 4

Brewing Materials ................................................................... 5

Researching Old Beers ......................................................... 10

Oasthou.es in Kent

Part 2. Making Old British Beers ............................................. 15

Brewing methods for formulations in this book .............. 15

Recipes .................................................................................... 19

Medieval Beers ............................................................... 21

Pale Amber and Amber Beers .. .................................... 25

Light Brown, Brown and Dark Brown Beers ............. 31

Stouts and Porters .......................................................... 39

.--------

-~ -:::-....,-~---...__~-

A typical si7Uill English Brewery

-

-

~--

Appendix 1. Home Roasting Pale Malt to Coloured Malts ... 45

Appendix 2. Colour Ratings of Roast Malt and Barley .......... 46

References ..................................................................................... 47

...-... "-.

~

.

~

-

.

..

. -

...

-.. . .

.

-

-

)

)

)

Introduction

Truman's XXK March Keeping Beer (1832)

OG90

A quality st rong pale ale with a fine hop charucter.

3.6 lb Pal' Malt

13! 4 oz Fuggles Hops (boil)

I; 2 oz Coldi11gs Hops (/at,)

1(10 oz. Coldi11gs Hops (dn;J

Method No.2, but acfd the late Geldings hops for the last

10 minutes of the boil, and dry hop with Geldings.

Mature for 8 to 10 months.

The Circle's interest in old beers originated in 1972 when the author

read a book A History of English Ale and Beer by H.A. MonktonO >.

This book not only showed the large part that Porter played in 18th

and 19th century· brewing, but also indicated how other wellknown beers such as India Pale Ale had changed since the early

1800s. An unwritten assumption pervading the book was that those

beers were history and no-one would drink their like again. The

author took this as a challenge, and suggested to the newly formed

Circle that researching, making and evaluating OLD BEERS should

be one of the Circle's core activities.

This proposal was enthusiastically adopted by the Circle. As

ultimately refined, it consisted of an annual programme of OLD

BEERS to be made (decided in January). The evaluation of the beers

was to be made at a Christmas function where the beers would be

accompanied by OLD BRITISH FOOD.

As the only Material Scientist in the Circle, it fell on the author to

carry out most of the research on beer formulations. However, the

production ·and eva luation of the ales and beers has been a

complete Circle effort and the names of all brewers who ha ve

contributed to this booklet are shown on the inside front cover.

As a result of the·Circle's efforts since 1973, we now know that

beers ranging from the merely interesting to the superb can be

obtained by researching and making old formula tions. The

problem, however, is how certain can we be that the product we

have made with modified recipes, modern malts, modern hops,

modern yeasts and possibly untypical water is a fair copy of the

beer as originally made.

The only honest answer is that for the majority of beers described

there is no way we can ever know~ The exceptions are those beers

that remained virtually unchanged up to 1914. In 1973 when we

started the programme, there were about some people aged 79 and

over who were in their 20s in 1914. Such people might remember

drinking pre-1914 beer.

W~ encountered one such person by accident. On Christmas Eve

I left a few pints of draught Whitbread's 1850 porter with a brewing

friend, Don Hebbs. I heard the rest of the story two weeks later. On

vii

)

Ole. __Aish Beers

Christmas morning he asked his daughter's fiance's grandmothera spry old lady of 86- if she would like a glass of Guinness. On

getting her approval, he went and fetched a pint of my Whitbread's

porter. The old lady took a swig and turned a beady eye on Don.

she took another long pull, looked him straight in the eye and said

"That's not Guinness, that's London porter! Where on-earth did you

get that?" Don was totally flabbergasted. He did not know that the

old lady knew what porter was, never mind able to recognise it. It

transpired that she, as many girls did at the time, entered domestic

service when she was 14. As was the custom then, she was given so

many pints of porter as part of her board. When porter disappeared

~he switched to Guinness. It took only a third of a pint of porter to

set those memories flooding back. That incident was the best

unsolicited testimonial we are likely to get.

The next best occasion occurred in 1988 when I took some 1871

Younger's Ale No. 1 back to the Scottish Brewing Archive. An exYounger maltster-cum-brewer aged 78 took it around to the

Younger's home for elderly ex-employees and shared it with a few

friends aged 83 and 85. They were very impressed. They recognised

it as Ale No. 1 and thought it was better than· the earliest samples

they could remember from the early 1920s. The essential difference

between the 1871 and the early 1920 versions was that the OG in

1871 was 102, whereas in 1923-24 it would have been ~5.

Our third example, though less definitive than the first two, is

worth mentioning. There are a number of beers ·available

commercially which bear a close resemblance to our 'Original India

Pale Ale'. I came across one such, an American east coast beer

called Ballentine's India Pale Ale in 1966 before we started our

programme. The carton's description of the beer was: "As made for

the India trade, matured in wood for one year." The OG was

probably nearer 55 than 68-70 but the family resemblance was

good. Another is Young's (London) Strong Export Bitter. One

would expect this to be descended from the IPAs of yore and again.

at an OG of 62, the resemblance is there.

It is too much to hope that we will see many more of such

encouraging confirmations of our work. Many of our beers

vanished long before 1914, and there is but a small, fast-dwindling

population of old drinkers to call upon.

Part 1

Historical Notes

General

The history of British Ales and Beers can be conveniently

divided into four main periods. The period where the main

beverages were Anglo-Saxon unhopped ales lasted until about

AD 1400. The struggle between unhopped ales and hopped

beers lasted from AD 1400-1700. The full flowering of British

brewing took place between AD 1700-1914. During this period,

virtually every combination of malts, roast malts, other grains

and hops was to be found somewhere, at original gravities

ranging from 40 to 140. The post -1914 period is characterised

by the takeover and closure of many thousands of breweries,

thus drastically reducing the choice available. In addition the

tax system in the UK has been biased against high gravity

beers. This has led to a continuous reduction in the original

gravity of standard beers such as bitter and the elimination of

many high gravity beers by the smaller brewers.

Nomenclature

l

All trades and crafts have their own private vocabulary in

which special meaning is attached to a word that is in general

use. For example, the word 'mash' in brewing does not mean

to crush or to macerate, but it refers to the process of steeping

crushed malt with hot water to convert the starch into

fermentable sugars. It is assumed that anyone wanting to use

this book · will be familiar with present-day brewing terms.

However, when looking back over a period of 700-800 years

one must be aware that words sometimes change . their

1

viii

r.

(

J ritish Beers

)

Hh

meaning with time. The most important of these are as

follows:Ale

Beer

Stale

Stout

Porter

Malt

Brown

Malt

Before about AD 1700 this referred specifically to a

malt beverage made without hops. With the eclipse

of unhopped drinks, the word became to mean a

beer made in the British style, i.e. made using top

fermenting yeast at room temperature; 1:5-21 °C (60700F).

Pre -1700 it meant a hopped malt beverage distinct

·from Ale. With the eclipse of unhopped Ale the

word beer became a general term covering all

hopped malt drinks. Lagers, ales and barley wines

are all types of beer.

Up to the late nineteenth century the word meant

'old and mature', and stale ale or porter cost more

than ordinary ale or porter. Nowadays it means old

to the point of not being drinkable.

The old English meaning of the word meant strong,

tough, hearty. This meaning also applied in

brewing, and up to about 1840-1850 a stout beer

meant a strong beer. It was only after 1850 that the

term came to have its current meaning of a dark

full-flavoured beer made using black malt or roast

barley<2>.

In the nineteenth century, in England and Scotland,

the description porter malt meant brown malt. In

ireland, however, it meant pale amber malt.

This was also known as blown malt due to the

popping of the malt during production.

Weights and Measures

When interpreting old sources of brewing information,

attention has to be paid to changes in weights and measures

that have occurred over the past five centuries.

2

) al Notes

Barley and Malt

These were originally specified in units of volume. A bushel

was the volume of 10 gallons of water, and a quarter was equal

to 8 bushels. The standardisation of the weights of a quarter of

barley and malt at 448 lbs and 336 lbs respectively, does not

upset extracted data as these weights were set at the average

·

weights of the original volume measure.

In Scotland before 1840 a unit normally used for meal was

sometimes used for malt. The boll is 140 lbs and is divided into

4 firlots.

Coloured Malt and Roast Barley

i

!.

In Malting and Brewing Science<3> there occurs the comment:

"Transactions involving coloured malts have in the past been

complicated by the range of units of weight used" . Thus

coloured malts and roast barley were sold by the malt quarter

of 336 lbs, 280 lbs and 252 lbs, with 6 or 8 bushels to the

quarter. The author has only come across one set of ledgers

where malt quarters less than 336 lbs have been specifically

mentioned. In the Reid (London) ledger for 1837, brown malt

and roast barley were bought in at 244 lbs per quarter, and in

1877 at both 228 lbs and 244 lbs per quarter.

The absence of a specific reference to quarter weights less

than 336 lbs does not guarantee that a 336 lbs value was in

use. This sort of familiar information which did not change

was sometimes omitted from ledgers as being unnecessary!

Gravity

Prior to 1760 there was no easy, practical method of

measuring wort and beer gravities. The application of the

hydrometer (saccharometer) to brewing, particularly by

J.Richardson< 25l in 1784 led to the system of recording

gravities as brewers' pounds per barrel which is still in use.

The gravity of a wort or beer in brewers' pounds is defined as

the weight of 36 gallons of the wort minus the weight of 36

gallons of distilled water. Brewers' pounds can be changed

3

Ole.. l tish Beers

into SG by multiplying by 2.77, or by. the use of conversion

tables.

Cask Sizes

The Ale barrel was first standardised at 30 gallons, in 1420

AD, and the Beer barrel at 36 gallons where it has remained

since. With the demise of the unhopped ale around 1700 AD,

the Ale barrel fell into disuse. In old sources of brewing

information one finds .reference to some of the less common

cask sizes and they are as follows: a Pin is 41;2 gallons; a Six is

6 gallons; a Firkin is 9 gallons; a Kilderkin is 18 gallons; a Barrel

is 36 gallons; a Tierce is 42 gallons; a Hogshead is 54 gallons; a

Puncheon is 72 gallons; a Butt is 108 gallons, and a Tun is 216

gallons.

Brewing Methods (Old versus Present-Day)

Grinding and Mashing Malt

Apart from better control of these processes, e.g. the use of

thermometers for accurate temperature control and hydrometers to control specific gravity, there has been no important

changes in these processes

Separating the Wort

The process of sparging, i.e. sprinkling the mashed grain with

hot water at the same time as wort was run off from the

bottom of the mash tun, seems to have originated in Scotland

in the late eighteenth century and was in widespread use in

the UK by the early nineteenth century. Prior to this development; removal of the whole of the fermentable material

from a batch of grain was accomplished by a system of

multiple mashing. After an initial mash of about one hour,

taps were opened and as much wort as would separate freely

was collected. Further hot water was added to the grain and a

second mash performed for 45 minutes or so. The draining

and remashing was repeated up to four times to produce a

4

)

Hi~

) al Notes

series of worts of decreasing gravity. These were usually

boiled separately with hops; the spent hops from the first

mash being re-used as part or whole of the hops for successive

mashes. In this way, one batch of grain yielded ales ranging

from an OG over 100 down to table ale of OG 30-35. Some

brewers blended the four resulting worts to control the OGs of

the hopped worts or to reduce the number of ales. Some

brewers continued double mashing into the late nineteenth

century. Our experiences of making the same ale by simple

mash and sparge and by double mashing suggests that the

differences in the resulting ales are marginal.

Brewing Materials

As with all agricultural crops, brewing materials have been

under continuous change and development during their

recorded history.

Hops

In 1950 the UK hop crop consisted of 20% Goldings and

Golding type, 77.5% Fuggles, and 2.5% others< 3>. In 1850 there

was Golding plus at least eleven other varieties. Some of these

were of local significance only, and many were coarse hops

grown for high yield and resistance to disease rather than any

intrinsic merit. Fuggles, generally availaole from 1875,

eventually superseded them all. In 1750 there were about six

well established varieties: Farnham Pale, Canterbury Brown,

Long White, Oval, Long Square Garlic, and Flemish. Farnham

Pale was regarded as the best quality hop but with the

introduction of Golding in 1795 it became just another hop

that was eventually superseded by Fuggles<4 >.

With the above history there see_med to be little point in

using any hops other than Fuggles or Fuggles plus Geldings

as copper hops, or Goldings alone as aroma hop, in our

programme.

5

J

0" ) itish Beers

)

His'

) 1Notes

~~

~

)S,

~

~

~~

'!

.~

.~

~j

:j

In translating old recipes where the hop variety is not

given, however, it is safer to assume that these were coarse

hops with a l()wer bittering potential than Goldings (5.5%) or

Fuggles (4.5%) and assume a bitter resin content of 4%.

Pale Malt.

Before 1820, improvements in barleys for malting were ·made

on a very local scale and improved strains were usually

named after the districts in which they were grown. The first

nationally grown barley was produced from selections made

in about 1820 by the Rev. J.B. Chevalier, and Chevalier became

the premium malting barley for most of the rest of the

nineteenth century. Since then there have been several waves

of improved malting barleys. Between the two world wars

Spratt-Archer and Plumage Archer were favourites giving

way to Proctor post-1950. Proctor is currently under competition from ne~ varieties such as Zephyr and Maris Badger<3 >.

The salient fact is that we cannot obtain malt made with pre1914 barleys and the crucial question is does it matter. A great

de~l of ·t he effort put into improving barleys has no direct

effect on the flavour of the resulting beer. The farmer needs

high yield, disease resistance and a short stiff straw; the

maltster needs a thin husk, even and ·reliable germination and

even modification; and the brewer wants a high diastaticactivity to cope with un~alted adjuncts such as flaked barley.

On balance, we believe that using malt made from

currently grown barleys instead of the old original varieties,

will have made only marginal changes in flavour and quality

of the beers we have made and enjoyed.

An additional piece of evidence for thinking that differing

barley varieties have only minimal effect on beer flavour is

contained in the ledgers of Younger's Brewery (EdiJ:lburgh)

for the 1870s. These show that in any one year, barleys for

malting or malted barleys, were obtained from Scotland,

England, Ireland, France, the Baltic area, the Black Sea area,

North Africa and occasionally North America. There are no

6

records in the ledgers of complaints about beer variation,

caused by this wide variety of raw material. The ledgers also

suggest that the nineteenth century brewers were a great deal

less hag-ridden about making absolutely identical brews than

the present-day commercial brewers.

Pale malt only became available from about 1680 when

coke began to be freely available for the direct, or preferably,

the indirect curing of malt(2). The lack of control over the

previous methods using fierce hardwood fires, or burning

straw, meant that the outer part of the malt was caramelised.

Ales made with such malt would have been nut-brown in

colour.

With the rise in popularity of India Pale Ales in the early

nineteenth century, a special malt was produced that was

even paler than pale malt. The maximum cure temperature

was 150° F compared with 170 -180°F for pale ale malt<Sl. The

product, known as East India Malt (sometimes white malt),

was probably Closer to present day lager malts than current

pale ale malts. (It is interesting to note that Youngers in 18501870 made their pale and export ales largely with foreign malt

which was probably lager malt style!)

Coloured Malts

While variations in beer produced by using pale malts made

from different stra_ins of barley seem to be minimal, changes in

beers as a result of changes in coloured malts were highly

significant. Up to 1817 the darkest malt available was brown

malt dried over a fierce hardwood fire. Any attempt to take

the malt to a darker colour led to a runaway reaction which

turned the malt into charcoal. In 1817 D.Wheeler invented the

cylindrical drum roaster incorporating water sprays which

could be used to quench the roasting grain instantly< 6>. This

enabled controlled production of roast malts ranging from

amber, brown and chocolate through to black. Similarly raw

barley could be roasted to colour comparable to black malt<2l.

7

Oh.. ) itish Beers

This development w as rapidly exploited by porter brewers

and w ithin five years most London porter had b een reformulated to replace most of the brown malt by pale malt plus a

little black malt.

Another coloured malt favoured in Scotland, and Ireland

(where it was known as porter malt) in the nineteenth century

was pale amber. Its colouring power was about half that of

ordinary amber malt<7>. It was fully diastatic. It is no longer

readily a vailable. Provided allowance is made for its poor

diastatic performance carapils (or caramalt) can be used as a

substitute for pale amber.

A late introduction to the range of coloured products was

Crystal Malt. The freshly m alted barley was heated under

high humidity to mash the starch to fermentable sugars inside

the ba rley grain. Further dry roasting caramelised these

sugars w ith the production, in freshly broken grains, of a dark

brown glass-like appearance. The process for producing

crystal malt seems to have been patented in the 1840-1850

period . Little actual use seems to have been made of crystal

m alt before 1880 however<B>. The middle range of crystal malt

has a colouring power similar to that of brown malt. Whereas

m odern brown malts have no residual diastatic properties and

therefore cann~t be made the major part of a grist, crystal malt

is pre-mashed and does not have that limitation. The flavour

of crystal malt is similar though not identical to that of brown

malt and we have found it useful to replace part of the brown

malt in some old beer grists with crystal malt to enable a

satisfactory extract to be obtained. For example, AD 1800

Dorchester Ale was originally made with two parts amber and

1 part brown malts· (rapidly cured over a hot wood fire). Such

a grist obviously mashed satisfactorily in a way that modern

amber and brown malts do not. The recipe given in this book

is thus one which is designed to make a close approximation

to the original beer w ith materials currently available.

Pale amber, amber and brown malts may not be readily

available to individuals wishing to make some of the recipes

8

)

His•

)al Notes

in this book. It is not difficult, however, to make small

quantities of these sp ecial malts at home, and instructions for

d oing this are given as an appendix.

Yeast

After malt (and its roasted products) and hops, mos t brewers

would agree that the next most important factor determining

beer character is the strain of yeas t. This importance arises in

two ways. The metabolism of the yeast during fermentation

results in a nu mber of products such as diacetyl, aliphatic

alcohols and esters that a re important in beer flavour.

Secondly the alcoholic tolerance of the yeast, and its ability to

ferment the maltotriose component of wort determines the

resid ual specific gravity (and hence residual sweetness and

pala te fullness) of high OG beers. Both of these effects vary

with the strain of yeast.

However the technology of yeast is a comparatively recent

d evelopment. It was only in 1876 that the function of yeast

d uring fermentation was elucidated by Pasteur<9l . With few

exceptions we know nothing about the yeasts used to make

the beers we have stu died. The exceptions are those brewers

that have never replaced the yeast used in the br ewery for

very long periods of time, for example the Guinness Stout

brewery. These examp les are, however, very special cases.

Our approach has been to use the most app'r opriate modern

yeast but look to see whether the final gravity reached is the

best for tha t beer. For example, Dorchester Ale can be

fermented with modern yeast to below an SG of 20. At this SG

the flavour balance is not right and raising the SG to 30

(comparable to mod ern Russian Stout) produces a m arked

improvement in balance. It seems entirely plausible that the

yeasts used in 1800 w ould have left such a gravity na turally in

Dorchester Ale.

Water

The importance of water used to brew beer has been known

for hund reds of years. Burton-on-Trent, with its very hard

9

~-------------------------------------------------------------

L-.h ritish Beers

water has a reputation for producing good ale that goes back

to the eighteenth century. Up to the start of the nineteenth

century brewers could only select the most suitable of the

locally availabl~ sources of water- well, river or stream - and

make the best of it. Even in the late nineteenth century the

only water treatment recommended to brewers was that oversoft waters could be hardened by boiling with gypsum

(calcium sulphate) plus a little table salt<S>.

For making the high gravity, all malt, robust British beers

pescribed in this book only two types of water are needed. For

pale ales, export ales, strong ales and barley wines the water

(A) should have a total salt content of 800-1200 parts per

million (ppm), which should be high in calcium and sulphate,

and contain small amounts of sodium and chloride. For dark

beers such as mild ales, brown ales, stouts and porters the

water (B) should have a salt content of 250-450 ppm and

contain more sodium than calcium and more chloride than

sulphate.

The best approach is to obtain- from your local water

supplier an analysis of the water and use the instructions in

any of the better home-brew booksOO) to adjust the water into

the desired area.

Researching Old Beers

Reliable information on the formulation and processing of an

old beer is essential if that beer (or a close copy) is to be

reproduced. This is so even if it is subsequently decided to use

an alt~rnative item readily available now, for some original

material n~ longer accessible.

There are only two primary sources' of information about

OLD BEERS. If they can be accessed, brewing iedgers compiled

by. a brewery at the time the beer was brewed form the most

reliable sources. Even with these, errors of interpretation can

occur because the ledgers were never intended to be read by

someone with no first hand knowledge of the brewery and its

10

)

h

) ical Notes

method s. Ledgers with pre-printed headings are not common

before 1840. Pre-1840 hand-written ledgers are obviously

more difficult to read and sometimes degenerated into little

more than an aide-memoire for the brewer. T hese often

omitted essential details such as the quantity of beer brewed ,

presumably because only one quantity (the full capacity of the

plant) was ever brewed, so there was no point in mentioning

it. A book is now available containing a comple te list of all

brewing archive data known within the UK0 1>.

The second most useful sources are old books o n brewing.

These are a mixed bag. Some are obviously written first-hand

by experienced brewers, but others are only compilations of

information at second, third or fourth hand.

Other sources include record s and accounts of medieval

Abbeys and large estates owned by the landed gentry. These

were often self-su fficient in home brewed beer.

As with all historical information, the further back in time

one goes the less information is available. There a re a number

of reasons for this. The range of beers made in medieval times

was smaller than that made by a large nineteenth-century

brewery. In the absence of cheap methods of information

recording and storage, e.g. typewriters and printing presses,

only the bare minimum of information was kept. Also, when

brewing was a craft activity controlled by Guilds the dissemination of information outside the Guild was discouraged .

There are quite a few beers that exist only in name and by

reputa.tion; no factual information having survived.

Is it worth making?

There is nothing more annoying .than spending a lot of time

extracting· information abou t an OLD BEER, breaking the

formulation down to home brew proportions, making it and

evaluating it; only to find that one could have bou ght a similar

beer in a local off-licence. What is needed is a simple method

of classifying beers so that one can see if an OLD BEER has no

11

Old ,

)

J sh Beers

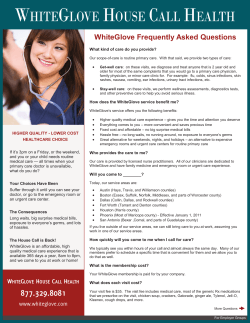

Figure 1. Original Gravity vs. Colour

lW~

25

48

130

120

~

.23

22

110~

,e. 100

35 36

24

•

21

t

20

>

c<S

90

59

58

19 . .

<a

·~

60

~~n

l?

· ~::

47

46

.....

...

•

34

37

40

80

0

2

32 28

4l;

44

70 -13T 6

••

•

•

., .•

')"')1

•

27

•

60 . . .10

30

26

50

~

~ .

J

•• ;

57

56

sse

54

53

•

29

51 52

30

12

Amber

Light

Brown

Brown

Dark

Brown

) 1Notes

existing equivalent. The me thod used by Durden Park is a

simple two-d imensional plot of original gravity versus colour

(Fig 1). The ori ginal gravity controls alcoholic strength,

maltiness and residual sweetness. The colour retlects the type

and amount of roast grain in the grist, a nd is a measure of

roast grain flavour in the beer. The other two factors w ith a

significant effect on beer character a re the hop rate and

sweetness (where this is greater than that left in a fully

fermented beer).

Sweetness above that of a fully fermented beer is fo u nd

only in some brow n ales and stouts and is relatively rare in

old beers. Differing hop ra tes are more of a problem. H op

rates expressed as lbs Hops per Quarter of Malt range from

zero for unhopped ale to 23 for some India Pale, and Export

Pale Ales. While there are fancy methods for red uci.n g 3 or 4

variables to a 2-dimensional graph, the interpretation of such

graphs is less im mediately obvious to the average ho me

brewer. It is better to keep the OG/Colour p lot and simply

rem ember that any one spot on the graph covers a range of

hop rates. Further comparison of these rates w ill enable one to

decide w hether an OLD BEER is too similar to an existing

commercial beer to be worth making. A bar chart of hop rates

found in old beers is shown in Figure 2.

Looking a t figure 1 in detail, the shaded L-shaped area

represents the regions well covered by present-day commercial brewing. Only oddball b eers in this area are worth

50

40

Pale

Am.ber

Hisl

Black

Key to figure 1

Historic beers have been plotted with the same numbers given in the

section on beer formulations. Contemporary beers are plotted with

the numbers given below.

101 Gale's Prize Old Ale

106 Marston'sOwd Roger

107 Young's Old Nick Barley Wine

102 Eldridge Pope'sHardy Ale

103 Young's Winter Warmer

108 GuinnessStrong Export

104 Theakston's01d Peculiar

109 Courage's Russian Stout

105 Greene King' s Suffolk Ale

13

'f

J

1

")l

~

il

i,

<'

~!

"~

)

Old u, dish Beers

considering, e.g. very high or very low hop rates. Outside the

shaded area commercial coverage is thin or in some places,

non-existent. It is a worthwhile exercise to plot existing

commercial beers falling outside this areas so that these slots

can be avoided.

,,

if

J

i'.t

20

The old recipes in this book were all made with malted barley,

some 7- 8 grades of roasted and caramelised malt and barley,

and leaf hops. We do not think it is practical to try and

duplicate this wide range of beers using the limited types of

malt extract available.

However, for those beers made only from pale malt and

hops a reasonable copy can be made using the palest available

liquid or powder malt extracts and fresh hops. Such beers are

unlikely to have the body and palate fullness of the same item

produced directly from malted barley.

·r-;

~

15

·'

l

I

l

I

j;

f!

Part 2 Making Old British Beers

Brewing methods for formulations in this book

.,'

,,

)

10

I

India Pale Ales

5

&

Export Pale Ales

1. Suitable for OGs up to 80

0

0

2

Figure 2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Hop Rate (lbs per barrel)

16

18

20

Add hot water to the ground grain to produce a stiff mash a t

66°C (150°F). Maintain 66±1° C (150±2° F) for three hours

then raise the temperature to 77° C (170°F) for 30 minutes.

Sparge slowly with water at 82-85° C (180 -185° F) to obtain

the required volume. Boil with hops for 11h hours. Cool.

Strain and rinse the hops. Adjust to the required OG by the

addition of cold boiled water or dried pale malt extract as

needed. Ferment with good quality ale yeast. Dry hop with

11to oz Geldings.

2.

Suitable for OGs over 80

a) Traditionally these were made by · using the first wort

drained from a large batch of malt, the rest of which went

into lower gravity beers. It is possible to duplicate this

procedure on the small scale by:

i) using a very stiff mash

ii) sparging very slowly

14

15

~

,e

II'

6.~. dritish Beers

)

Brew

)Methods

I#

~~

ti.

~~

iii) cease collecting wort when the gravity has dropped to

a critical value- about 15 below the beer QG.

Subsequent boiling with the hops for 11I 2 hours raises the

gravity to that specified.

The wort remaining in the grain can be sparged out to

make a second beer with an OG in the range 40-60.

However, the making of a second beer can be avoided, if

only the main beer is wanted, by using method 2 b.

•1

b) Proceed as in method 2 a) until the wort collected has

fallen in SG to 15 below the beer OG. Change the vessel

receiving the wort and continue sparging slowly until the

SG of the second wort drops to 50 below the beer OG.

Boil the second, weaker wort until the SG (adjusted to

room temperature) has risen to 15 below the beer OG.

Add the first wort and raise to the boil. Add the hops and

.boil for 11/z hours.

Continue and complete the fermentation as in method 1.

Maturing

The great majority of beers in this book would have been

matured in wooden barrels for serving draught, or bottled in

corked bottles for 'home sales' or export. Neither method is

particularly convenient for home brewers.

PVC Adhesive Tape to

Secure Boat to Carboy

Heavy

Polyethylene Film

/

The following method has been found suitable for maturing, for up to a year, beers intended for serving draught.

When the initial fermentation is complete (say 3 weeks) the

beer is siphoned into a suitably sized glass container with a

narrow neck. The beer should overlap the base of the neck. A

loose-fitting glass or plastic tube, closed at the lower end, is

inserted into the neck and prevented from slipping too far into

the beer by PVC adhesive tape - see diagram. The size of the

plastic boat should be as large as is practicable to minimise the

exposed beer surface.

About ·half a teaspoon of sodium metabisulphite crystals

plus a few crystals of citric acid are placed in the boat. The

carboy or demijohn neck is then covered by several layers of

polyethylene film held in place by a heavy elastic band.

This seal allows carbon dioxide from any secondary

fermentation of residual wort carbohydrates to escape; limits

contact with the air; and provides enough sulphur dioxide in

the airspace to inhibit ye~st or bacterial growth on the small

exposed beer surface. When needed the beer may b e siphoned

into a fresh container, fined if necessary, and then conditioned

in a plastic pressure barrel for draught dispense.

Bottling high gravity old ales has to be done with care. The

safest type of bottles to use are those which can be checked for

development of excessive pressure by rapidly opening and

resealing. The old-fashioned internal screw-stopper bottles are

ideal but virtually unobtainable. The next best are the swingtop bottles similar to those used for some continental lagers.

Because some secondary fermentation will usually take place

in bottle, the priming sugar should be restricted to a quarter or

a third of normal, i.e. about 1/ 4 oz per gallon.

Strong Elastic Bands

~

Cut-off Plastic Bottle or

Sealed Plastic Tube

16

Bisulphite and

Acid Crystals

/

./'

17

)

)

)

Recipes

Medieval Beers

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Gruit Ale (unhopped, ca. 1300)

Gruit Ale (unhopped, ca. 1300)

Medieval Household Beer (1512)

Medieval Household Beer (1577)

Medieval Household Beer (1587)

Welsh Ale (unhopped, ca. 1400)

MUM (unhopped, Late 17th Century)

Ebulum (Unhopped Elderberry Ale, 1744)

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

Pale Amber and Amber Beers

9

10

11

'•

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Younger's Export Ale (1848)

Usher's India Pale Ale (1885)

Usher's 60/- Pale Ale (1885)

Simond's (Reading) Bitter (1880)

Original India Pale Ale (1837)

William Black's X Ale (1849)

Younger's Ale No.3 (Pale, 1896)

Younger's Imperial Ale (1835)

London Ale (1820)

William Black's XXX Ale (1849)

Alexander Berwick's Imperial Ale (1849)

Litchfield October Beer (1744)

William Black's Best Ale (1849)

Keeping Beer (1824)

Younger's XXXS Ale (1872)

Wicklow Ale (Ireland, 1805)

Burton Ale (1824)

25

25

25

26

26

26

27

27

27

28

28

28

29

29

29

30

30

Light Brown, Brown and Dark Brown Beers

26

27

28

Maclay's 56/ - Mild Ale (1909)

Mild Ale (London, 1824)

Ushe r's 68/ - Mild Ale (1885)

31

31

31

19

~I

~

'

.

'

I~

J

L-.r-.t~ritish Beers

...~

11:

l~

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

~;

~~

~~

!l :'

~-

ii:

li·

!i.l

i [~j

l.!i·

r

ij',.

l

']!

~

.~

~.:

il

.U

Kingston Amber Ale (ca. 1830)

Younger's 60/- Ale (1871)

Younger's 80/- Ale (1872)

Younger's 100/- Ale (1872)

Younger's 120/- Ale (1872)

Younger's 140/- Ale (1872)

Younger's 160/- Ale (1872)

Younger's 200/- Ale (1910)

Younger's Ale No.1 (1872)

Younger's Ale No.2 (1872)

Younger's Ale No.2 (London, 1872)

Younger's Ale No.3 (1872)

Younger's Ale No.3 (London, 1872)

Younger's Ale No.4 (1866)

Belhaven Ale No.4 (1871)

Belhaven XXX (1871)

Younger's XXXX Ale (1896)

Younger's XXXX Stock Ale (1896)

Dorchester Ale (ca. 1800)

Younger's Majority Ale (1937)

Medieval Beers

32

32

32

33

33

33'

34

34

34

35

35

35

36

36

36

37

37

37

38

38

Recipes per 1 gallon

1

Gruit Ale (unhopped, ca. 1300)

Ref (15)

OG80

Plain ales ·from fermented barley wort were undoubtedly

made in the pre-hop era. However, where possible herb

flavou rings would have been added to offset the bland

flavour of plain ale.

1% lb Pale Malt

1112 lb Carapils

1112 gram each of Myrica Gale (Sweet Gale),

Ledum Palustre (Marsh Rosemary) and

Achillea Millefolium (Mil/foil or Yarrow)

Method No.1, but in place of hops, boil the herb m ixture with

the wort for 20 minutes.

Mature for 4 months.

Stouts and Porters

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

'[

It

I .

~~

20

Maclay's 63/- Oatmeal Stout (1909)

Usher's Stout (1885)

London Porter (ca.1800)

Whitbread's London Porter (1850)

Younger's Export Stout (1897)

Younger's Double Brown Stout (1872)

Younger's Porter (1848)

William Black's Brown Stout (1849)

Whitbread's Double Stout (1880)

Original Porter (1750)

Whitbread's Triple Stout (1880)

Younger's XXXP Export Porter (1841)

39

39

40

40

40

41

41

41

42

42

43

43

2

Gruit Ale (unhopped, ca. 1300)

Ref (15)

OG 50

Repeat the procedure for the OG 80 Gruit Ale but use 11; 4 lbs

pale malt, % lb carapils and only 1 gram each of the herbs.

Mature for 3 months.

u

21

)

Beers

3 Medieval Household Beer (1512)

Ref (2)

) ieval Beers·

5 Medieval Household Beer (1587)

Ref (14)

OG65

OG70

The hop rate is beginning to approach modern p ractice. The

amber malt is needed to reproduce the nut-brown character of

medieval .beer. The beer character is similar to modern high

gravity light mild ale.

All malt in 1512 would have been at least pale amber in

colour, producing a pale brown beer. The malt mixture given

above should be a reasonable substitute. When first grown in

the UK, hops were an expensive commodity. In addition, the

anti-hop lobby blamed hops for all manner of human

problems from gout to flatulence. Medieval beers were thus

made with (by current standards) tiny amounts of hops. This

is a pleasant malty beer superior to American malt liquors.

1% lb Pale Malt

12 oz Amber Malt

2112 oz Wheatmeal

2112 oz Oatmeal

112 oz Fuggles or Go/dings Hops

21!4 lb Pale Malt

11!4 /b Amber Malt

1/s oz Hops

Method No.1, but simmer the wheatmeal and oatmeal in

boiling water for 10 minutes before adding to the malt mash.

Mature for 3-4 months.

Method No.1, but boil hops for 2 hours.

Mature for 4 months.

~ I

(

6

4

Medieval Household Beer (1577)

Ref (13). ·

Ref(l)

OG70

An appealing spiced Ale for drinking on a cold night.

OG55

A malty beer superior to American malt liquors.

1112 lb Pale Malt

12 oz Amber Malt

2112 oz Wheatmeal

2112 oz Oatmeal

114 oz Hops

Welsh Ale (unhopped , ca. 1400)

'··

3 lb Pale Malt

5 oz Light Malt Extract Powder

.

12 g cinnamon, 6 g Ginger, 3 g Cloves, 12 g White pepper

1!2 pint Honey

Method No.1, but mix the wheat and oats with boiling water

and simmer for 10 minutes before adding to the malt mash.

Process the pale malt to produce 1 gallon of wort u sing

method 1. Ferment with ale yeast. When nearly finished, add

the malt extract powder dissolved in a pint of water, plus the

other ingredients. Referment, adding sugar if necessary to

produce a final gravity of 15-20. Strain, Settle and bottle.

Mature for 3-4 months.

Mature for 6 months.

23

22

........aa............~s.....~aB. .oaB~

ij

Hlr

Ok

)

\

J tish Beers

ru.

ift.!

l

.,~ I

7 MUM (unhopped, Late 17th Century)

Ref (1)

. I

ll,j

One of the best unhopped ales.

~~~I

Recipes per 1 gallon

3 lb Wheat malt

1 lb Pale Malt

112 lb rolled Oats

112 lb ground beans.

1 gram each of Cardus Benedictus, Marjoram, Betony, Burnet,

Dried Elderflower, Thyme, Pennyroyal

1112 gram Crushed Cardamom seeds

112 gram Bruised Bayberries

~I

ll

Il.

!

Method No. 1, but simmer oats and beans for 20 minutes

before adding to malt mash. Ferment with ale yeast. After 3-4

d ays rack from the yeast deposit and add the other

ingredients. Infuse for 10 days. Strain and allow to clear, then

bottle.

1

Mature for 8 months.

I

I

r

l

l

Pale Amber and Amber Beers

OG80

8

Ebulum (Unhopped Elderberry Ale, 1744)

Ref (16)

OG60

A medium gravity India type pale ale.

2112 lb Pale Malt

2113 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No. 1

Mature for at least 8 months.

10 Usher's India Pale Ale (1885)

Ref (16)

OG60

A clean, bitter, refreshing p ale ale.

Ref (12)

OG85

Attractive in its own way. Resembles some Belgian Fruit

Beers.

4 lb Pale Malt

1112 lb Ripe Fresh Elderberries

Use method 2(b) to produce one gallon of wort at OG 100 (or

dissolve light :r:nalt powder in water to give the same). Add

the elderberries. Boil for 20 minutes; cool and strain. Ferment

with ale yeast.

Mature for at least 6 months.

9 Younger's Export Ale (1848)

2.6 lb Lager Malt

1112 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No.1

Mature for 8 - 9 months.

11 Usher's 60/- Pale Ale (1885)

Ref (16)

OG60

A typical pale ale of the period.

2112 fb Pale Malt

%ozHops

Method No.1

Mature for at least 3 months.

i

I'

I

I

I.

I

24

25

'I

I

I

i

~I

01~

)

J tish Beers

Pale and /

) er Beers

11

I

I .

!

12 Simond's (Reading) Bitter (1880)

Ref (24)

OG76

A robust, slightly sweet bitter with real character.

The strongest of Younger's Export Pale Ales.

2112 lb Pale Malt

I

:,

Ref (16)

1/b Pale Malt

2 lb Lager Malt

1112 oz Go/dings Hops

· 7 oz Carapils or 3 oz Carapils + 2 oz Amber Malt

1 oz Fuggles or Go/dings Hops

0.15 oz Goldings Hops 'late'

,,il

j

-!

15 Younger's Ale No.3 (Pale, 1896)

OG62

Method No.1

Method No.1, but add the 0.15 oz Geldings hops for the last 5

minutes of the boil.

Mature for at least 8 months.

Mature for at l~ast 3 months.

16 Younger's Imperial Ale (1835)

Ref (16)

OG80

13 Original India Pale Ale (1837)

Ref (21)

OG70

The recipe corresponds to the heaviest I.P.A shipped from

Burton in the 1830's according to the reference. Simonds of

Reading were shipping an almost identical formulation (2.9 lb

pale malt plus 21/ 4 oz hops) in 1880.

3 lb Pale Malt

2112 oz Go/dings Hops

Excellent Strong Ale.

Method No.1

Mature for at least 6 months.

Ref (20)

OG85

Mature for at least 8 months.

OG75

3 lb Pale Malt

1213 oz Go/dings Hops

17 London Ale (1820)

Method No.1

14 William Black's X Ale (1849)

A high quality strong pale ale.

A stron~ ale heavily hopped.

Ref (18)

3112 lb Pale Malt

3 oz Goldings Hops

Method No. 2(a) or 2 (b).

Mature for at least 1 year.

31!4 /b

Pale Malt

1.1 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No.1

Mature for at least 8 months.

26

.,

27

)-

"\

01u.

l ritish Beers

18 William Black's XXX Ale (1849)

l

l

/

Ref (18)

,,~:

21 William Black's Best Ale (1849)

OG90

OG 110

An excellent strong ale/barley wine

33{4 lb Pale Malt

1.7 oz Go/dings Hops

A superb barley wine.

Ref (18)

41/z lb Pale Malt

1.9 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No.1 or No 2.

Mature for at least 10 months.

Method No.2

Mature for at least 10 months.

t',,

I

Pale and Aufber Beers

19 Alexander Berwick's Imperial Ale (1849)

Ref (1 6)

OG 90-92

22 Keeping Beer (1824)

A high quality strong pale ale.

3% lb Pale Malt

1.1 oz Go/dings Hops

Very good Barley Wine

6 lb Pale Malt

13/4 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No.2

Mature for 1 year.

20 Litchfield October Beer (1744)

Ref (19)

OG 116

Method No.2 (a) The second beer makes a good bitter.

Ref (12)

Mature for at least 1 year.

OG 110

:l

Before temperature control became common after 1820, ale

brewers stopped brewing during the summer months. Strong

beers, made in October with fresh malt and hops and matured

over winter, provided stable beers for use the following

summer. They could be used as made, or watered down to

lighter beers. A very good Barley Wine with an individual

flavour.

4/b Pale Malt

1% oz Go/dings Hops

4 oz each of Oatmeal, Ground Peas, Ground Beans and

Ground Wheat

23 Younger's XXXS Ale (1872)

Ref (1 6)

OG 120

A very strong pale ale possibly exported to Russia.

6 lb Pale Malt

21!4 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No.1

Mature for at least a year.

Method No. 2(b) but first cook the adjuncts at the boil for 10

minutes before adding to the stiff mash made with the pale

malt.

Mature for at least a year.

28

29

")

01. J itish Beers

)

~

i

24 Wicklow Ale (Ireland, 1805)

Light Brown, Brown and Dark Brown Beers

Ref (17)

OG 125

r

Recipes per 1 gallon

A very strong, malty ale.

7 lb or 5112 lb Pale Malt (see method)

0.9 oz Go/dings Hops

26 Maclay's 56/- Mild Ale (1909)

Method No. 2(a) use 7lb Pale malt, 2(b) use 51h lb Pale malt.

An excellent middle gravity mild ale.

Mature for at least 1 year.

j

25 Burton Ale (1824)

Ref (19)

OG 140

]3/4 /b Pale Malt

314 oz Black Malt

3 oz Amber Malt,

10 oz Wheat Malt or 6 oz Wholewheat flour

\0.. 8 oz Go/dings Hops

----~

Method No. l.

A very strong, heavy, sweet ale for which Burton-on-Trent

was noted before it concentrated on Pale Ales, India Pale Ales

and Bitters.

10 lb or 6 lb Pale Malt

2 oz Hops + extra for the 2nd beer

Method No. 2(a) with 10 lb malt, also makes 11/2- 2 gallons of

lighter beer, or 2 (b) using 6lb.

Mature for at least

Ref (16)

OG60

11/z years.

Mature for 3 months.

27 Mild Ale (London, 1824)

Ref (19)

OG66

Very good full flavoured strong mild ale.

J 1j 4 lb Pale Malt

lib Carapils

1

4 oz Amber Malt

2;3 oz Go/dings Hops

-----

Method No.1

Mature for 3 months.

28 Usher's 68/- Mild Ale

Ref (16)

(1885)

OG80

i::

A high gravity mild ale virtually unique to Scotland.

2 lb Pale Malt,

0.9 oz Go/dings Hops

i

1113 lb Carapils

Method No. 1 or No.2

i:n

il

Mature for 4 months .

.

30

'--

.-,~ · .

31

I

f

01{

)

) tish Beers

Light Brown, Brown and Dark Brown Beers

29 Kingston Amber Ale (ca. 1830)

Ref (17)

OG60

32 Younger's 100/- Ale (1872)

OG80

Amber ales were popular in London. Ratios of amber malt to

pale malt varied from 3:1 to 1:1; OGs from 50 to 70, and hop

rates from 3; s to 3; 4 oz per gallon. Amber Ales are similar in

style to Theakston's Old Peculiar.

11/4 lb Pale Malt

11/4 lb Amber Malt

Ref (16)

Strong nut-brown ale. Less hopped than the Scotch Ale range.

2 lb Pale Malt,

13/4 lb Carapils

1 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No. 1 or No. 2

2 oz Chocolate Malt

314 oz Fuggles or Goldings Hops

Mature for 6 months.

Method No.1

33 Younger's 120/- Ale 0872)

Mature for 3-4 months.

OG 92-94

Ref (16)

Strong nut-brown ale.

30 Younger's 60/- Ale (1871)

Ref (16)

OG 60-62

The weakest of the Younger's Shillings Ale range. Almost in

the strong ale category by current standards.

11/2 lb Pale Malt

314

1 lb Carapils

2314 lb Pale Malt

2114 lb Carapils

1112 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No.2

Mature for 1 year.

oz Goldings Hops

Method No. 1

34 Younger's 140/- Ale (1872)

Mature for 3-4 months.

OG 104

Ref (16)

Barley wine strength nut-brown ale.

31 Younger's 80/- Ale (1872)

Ref (16)

OG70

See 100/- ale.

1213 lb Pale Malt,

0.9 oz Go/dings Hops

1113 lb Carapils

3 lb Pale Malt,

21f2[b Carapils

1.6 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No. 2(a)

Mature for at least a year.

Method No.1

Mature for 6 months.

32

33

<...

)

J ritish Beers

35 Younger's 160/- Ale (1872)

Ref (16)

Light Brown, Brown and Dar·

) wn· Beers

38 Younger's Ale No.2 (1872)

OG 126

OG94

A very strong nut-brown ale. The strongest in the Shillings Ale

range.

43/4/b Pale Malt

4 lb .Carapils

2.5 oz Go/dings Hops

A Scotch Ale with a slightly lower gravity than No. 1.

2112 lb Pale Malt

2 lb Carapils

1.7 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No.2

Method No. 2(a)

Mature for at least 10 months.

Mature for at least a year.

36 Younger's 200/- Ale (1910)

Ref (1 6)

OG 126

This seems to have been a Coronation Ale made to celebrate

the coronations of both King George V, in 1911, and King

George VI, in 1937.

41 !2 lb Pale Malt

3 1!2 oz Goldings Hops

Ref (16)

3 1/2 lb Carapils

Method 2(a). Extract 11/ 4 gallons of wort at the highest

possible SG. If below 100, pre-boil to this value (measured

cold) before adding hops and boiling for 21; 2 hours.

39 Younger's Ale No. 2 (London, 1872)

Ref (16)

OG 82

Scotch Ales for London sale were made slightly lower in OG

and somewhat higher in hop than those for sale in Scotland.

21/4 lb Pale Malt

l3/4lb Carapils

1.9 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No.2

Mature for at least 10 months.

Mature for at least 2 years.

40 Younger's Ale No.3 (1872)

Ref (16)

OG80

37 Younger's Ale No. 1 (1872)

Ref (1 6)

OG 102

The strongest of the Scotch Ales. A nut-brown dark barley

wine.

23!4/b Pale Malt

2 oz Goldings Hops

21t4 lb Carapils

Pale nut-brown ale similar to a strong mild ale. The most

widely drunk of Younger's Scotch Ales.

2 lb Pale Malt,

11h lb Carapils

1114 az Goldings Hops

Method No. 1 or No.2

Method No.2

Mature for at least a year.

34

Mature for at least 8 months.

35

)

Olu 2 itish Beers

41 Younger's Ale No.3 (London, 1872)

Ref (16)

Light Brown, Brown and Dark . ),n

44 Belhaven XXX (1871)

B~ers

Ref (16)

OG76

OG70

See Ale No.2 (London).

A nut-brown ale with a hop rate between that of the same OG

Shillings Ale and Scotch Ale.

1213 /b Pale Malt

1113 lb Carapils

1314 oz Go/dings Hops

12/3 /b Pale Malt

l 1!3lb Carapils

1114 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No.1

Method No.1

Mature for at least 8 months.

42 Younger's Ale No.4 (1866)

Mature for 6 months.

Ref (16)

45 Younger's XXXX Ale (1896)

OG74

This beer was only made for a limited period. It does not fit

neatly into the Scotch Ale series and looks like an export

version (higher hop rate) of Ale No. 3 (London).

13/4 /b Pale Malt

J1 tz lb Carapils

2 oz Go/dings Hops

Ref (16)

OG 75-76

Excellent strong mild ale.

]3/4 lb Pale Malt

11!4/b Carapils

1.6 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No.1

Method No. 1

Mature for at least 6 months.

Mature for 6 months.

46 Younger's XXXX Stock Ale (1896)

43 Belhaven Ale No.4 (1871)

OG68

Light nut-brown ale.

12 ;3 lb Pale Malt

1113 lb Carapils

1.4 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No. 1

Mature for 6 months.

36

Ref (16)

Ref (16)

OG98

A 'stock' version of an ale was of higher gravity and hop rate

than the ordinary version. w hen needed it could be diluted

down to strength with light beer or water.

2114 lb Pale Malt,

J3/4 lb Carapils

2 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No. 2(b)

Mature for at least 10 months.

37

01L

47 Dorchester Ale (ca. 1800)

)

)

J itish Beers

Stouts and Porters

Ref (17)

OG 100

The original recipe used only amber and brown malts; such

would not mash satisfactorily today. The grist has been

chosen to reproduce the character required in a form that is

easier to process. This is a dark brown barley wine.

1 lb Pale Malt

49 Maclay's 63/- Oatmeal Stout (1909)

Ref (16)

OG46

A chewy, satisfying stout.

2 lb Cn;stal Malt

1 lb Brown Malt

· 8 oz Diastatic Malt Syrup

11;4 oz Fuggles or Go/dings Hops

Method No. 2(b), but add the malt syrup to the wort before

boiling with the hops to break up any residual starch.

1114 lb Pale Malt

2 oz Amber Malt

4 oz Black Malt

3!4 lb Breakfast Oats

1 oz Go/dings Hops

Method No. 1, but mix the oats with 2 pints boiling water and

stand for 10 minutes before mixing with the malts. Mash at

155°F for 3 hours then 170°F for 1 hour.

Mature for at least 10 months.

48 Younger's Majority Ale (1937)

Recipes per 1 gallon

Ref (16)

Mature for 3 months.

OG 136

A blockbuster of an ale made at the birth of an heir to the

family for drinking at the 21st birthday party! The second

wort makes an excellent old-ale with OG 50-SS. The 1949 ale

was similar but had a hop rate of 11I 2 oz hops.

7/b Pale Malt,

5 lb Carapils

2 oz Go/dings H_ops

Method No. 2(a). Extract 1114 gallons of the strongest wort

possible. If the SG is below 120, pre-boil the wort up to this

value (measured cold) before adding hops and boiling for a

further 11/ 2 hours:

50 Usher's Sto:ut (1885)

Ref (16)

OG56

A typical full-bodied Victorian stout.

18 oz Pale Malt,

4 oz Black Malt

2 oz Crystal Malt

2 oz Brown sugar

1.3 oz Fuggles Hops

61!2 oz Carapils

2 oz Amber Malt,

2 oz Brown Malt

Method No. 1.

Mature for 4 months.

Mature for at least 2 years.

i

I.

t;

,,}

39

38

)

)

Olu 2 itish Beers

Ref (19)

51 London Porter (ca.1800)

'

'

Stoms and Porters

54 Younger's Double Brown Stout (1872)

OG60

Ref (16)

OG68

Porter recipes vary quite widely between different regions

and breweries. This formulation has the merit that it can be

made unchanged with modem brewing materials.

1114 lb Pale Malt

%lb Brown Malt

112

Double stout and d ouble brown stout were late nineteenth

ce!,"ltury labels for strong porter. Full-bodied and luscious.

1% lb Pale Malt,

31/2 oz Black Malt

1112 oz Go/dings Hops

lb Amber Malt

1.1 oz Fuggles or Go/dings Hops

1% lb Amber Malt

Method No. 1.

Method No. 1.

Mature for at least 6 months.

Mature for at least 6 months.

55 Younger's Porter (1848)

52 Whitbread's London Porter (1850)

Ref (22)

OG60

One of the circle's favourite old beers. Smooth, good balance

of roast grain and hop flavours.

21!4

/b Pale Malt,

Ref (16)

OG72

A full-bodied porter with an attractive soft roast grain

background.

1112 lb Pale Malt

7 oz Brown Malt

1112 lb Brown Malt,

1112 oz Black Malt

1112 oz Go/dings Hops

2112 oz Black Malt

1 oz Fuggles or Go/dings Hops

Method No. 1.

Method·No. 1.

Mature for at least 6 months.

Mature for at least 4 months.

56 William Black's Brown Stout (1849)

53 Younger's Export Stout (1897)

Ref (16)

Ref (18)

OG 76-78

OG 66-68

A mouth-filling strong Scottish porter, with a soft roast grain

flavour.

A full-bodied succulent stout.

1.1lb Pale Malt,

1.1/b Amber Malt

1.1 oz Brown Malt

] 1/4 oz Black Malt

1.8 oz Fuggles or Go/dings Hops

J1h lb Pale Malt,

1 lb Carapils

1

'2 12 oz Crystal Malt

2 oz Black Malt

1113 oz Fuggles or Go/dings Hops

Method No.1.

Method No.1.

Mature for at least 6 months.

Mature for 6 months.

40

41

~

)

(;. _ ) ritish Beers

57 Whitbread's Double Stout (1880)

Ref (22)

Stou

59 Whitbread's Triple Stout (1880)

)

Por ters

Ref (22)

OG80

OG95

Double stouts were strong porters. A heavy satisfying drink

f6racold evening.

The strongest of the London stouts. Similar to Russian Stout

but with a lower hop rate.

2% lb Pale Malt

3 lb Pale Malt,

14 oz Brown Malt,

3 oz Black Malt

1.2 oz Fuggles or Go/dings Hops

3 oz Black Malt

1113 oz Fuggles or Go/dings Hops

1 lb Brown Malt,

Method No.1.

Method No. 2(b)

Mature for 6 months.

Mature for at least 8 months.

58 Original Porter (1750)

Ref (22)

60 Younger's XXXP Export Porter (1841)

Ref (16)

OG90

OG 100

1750 porters would have contained mostly brown malt. These

cannot be made satisfactorily from present-day brown malts.

The above recipe is constructed to meet the contemporary

descriptions of 1750 porter, i.e. black, strong, bitter and

nutritious. It is one of the circle's favourite old beers. It might

not be authentic, but it is good! The Dorchester ale recipe is

probably as close to 1750 porter as can be made at present.

A full-bodied porter similar to Russian Stout. A softer and

quicker maturing version of this beer, that proved popular

with the Circle, can be made by using Carapils in place of the

Brown Malt.

31/2 lb Pale Malt

8 oz Brown Malt

8 oz Crystal Malt,

4 oz Black Malt

11/z oz Fuggles or Go/dings Hops

3 lb Pale Malt

J3/4 lb Brown Malt,

23;4 oz Black Malt or 31/z oz Roast Barley

3 oz Fuggles or Go/dings Hops

Method No. 2(b), but boil hops for 3 hours.

Mature for 1 year.

Method No. 2(b).

Mature for at least 10 months.

42

43

)

}

)

Appendix 1.

Home Roasting Pale Malt to Pale

Amber, Amber and Brown Malt

Some ingredients needed to make OLD BEERS might not be

readily available, in particular pale amber, amber and brown

malts. All three can be produced by roasting pale malt in an

ordinary domestic oven as described below. Carapils with a

colour number of about 25 can be used in place of pale amber up

to 45% of the pale malt in any grist. Even carapils, however,

might only b~ available by bulk purchase direct from maltsters.

Roasting Method

J 'Q't) de ,(eQ..$ .fc~ 1~ .... " ;

'3 oo cl ~~'R S'

3oo J

J

.\'-'(

4;! ~'"

.~ qs,...

~~\J d ~J~ OS J. 0 W\ ; r-

po.\('

0. <

~ ~

o. ~~'t.V"' """It

...

p~vi

r...A)~

Line a large baking tin with aluminium foil, and pour in pale

malt to a depth of 12 mm (1; 2 inch). Place in the oven (preferably

fan-stirred) at 100°C (230°F) for _!!5 minutes to dry out the malt,

then raise the tem~ralure to''fsooc (300°F). After a further 20

minutes remove 6 or 7 corns from the tray, slice across the centre

with a sharp knife and compare the colour of the starchy centre

with that of a few pale malt corns. The pale malt is almost pure

white; for pale amber the colour should be the palest buff, just

noticeably different from the pale malt. Continue heating until

this colour is obtained, usually about 30 minutes.

For amber malt, continue heating until the cut section is

distinctly light buff, usually 45 to 50 minutes. If brown malt is

needed, raise the temperature at this point to 175°C (350°F) and

wait until the cut cross-section is a full buff, i.e. about the colour

of the paler types of brown wrapping paper. When the correct

colour has been reached, remove the tray from the oven, allow to

cool and store the roast grain in an air-tight screw-top jar (large

kilner jars are ideal). If used soon after production, the flavour

imparted by home-roasted grain is superior to bought grain.

The roasting times given above are intended only as a guide

to producing the wanted roast grain Practical tests on the oven

available will enable home-brewers to adjus t the time and

temperature to produce the colour needed.

Crystal malt, which is usually available, has about the same

colour potential as brown malt but a more caramel-like flavour.

45

.

-~

)

}

)

Appendix 2.

References

Colour Ratings of Roast Malts and Barley

1

EBC t

Colour

Range

Type

Lager

3

1:1 mix with Pale Malt can

substitute for East India Malt

2.5-3

East India

Malt

4

Obsolete.

Pale

5

Standard Pale Ale Malt.

Mild Ale

6-7

Munich

16- 18

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Used for mild ales and dark

bitters.

used at double quantities can

replace Pale Amber Malt.

25-40

Carapils

2

Comments

Most

Used

· Colour

11

A pale crystal malt that can be

used to replace Pale Amber Malt.

12

13

14

15

Pale Amber

(Scotch Malt)

30-40 t

Amber

50-100

70

Brown

100-200

150

The main flavouring ingredient

in English and Scottish Porters.

Crystal

50-300

150

Being partly mashed inside the

grains it can be used to replace

Brown Malt in difficult recipes.

18

19

20

21

Obsolete - obtainable by special

order only.

Chocolate

900-1100

1000

Used in Stouts and Dark Brown

Ales.

Black

1200-1500

1350

Gives a sweet, acrid flavour to

Stouts and Porters.

Roast Barley

1000-1500

1200

Gives a drier, sharper flavour

than Black Malt.

----

t

:f:

European Brewing Co~wention colour numbers

Estimated from contemporary descriptions

I

16

17

22

23

24

25

Monkton. H.A. A History of English Ale and Beer. Bodley

Head, London 1966.

Corran. H.S. A History of Bmllittg. David and Charles,

London, 1975.

Briggs, D.E. et al.. Malting and Brewing Science. Chap. & Hall.

Vol1. Malt and Sweet Wort. 1981.

Vol 2. Hopped Wort and Beer. 1982.

Parker. H. H. The Hop IndustnJ. P.S. King and Son Ltd.,

London, 1934.

'Brewing' EncyClopaedia Britannica. Ninth Edition, 1876.

Wheeler. D. British Patent 4112 1817.

Tizzard. W.L. Theory and Practise of Brewing. London, 1857.

Stapes. H. Malt and Malting. 1885.

Pasteur. L. Etudes sur Ia Biere. Paris, 1876.

Line. D. The Big Book of Brewing. The Amateur Winemaker,

Andover, UK, 1974.

Richmond. L. and Turton. A. The Brewing Industry (A Guide to

Historical Records). Manchester University Press, 1990.

Anon. Town and Country Brewer. 1770.

Harrison. W. Description of England. 1577.

Bickerdyke. J. Curiosities of Ale and Beer. 1886.

Patton. J. Additives in Beer. Patton Publications, Swimbridge,

Barnstaple, UK, 1989.

Brewing Ledgers held at the Scottish Brewing Archive, HeriotWatt University, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Nithsdale. W.H. and Martin. A.T. Practical Brewing. First

Edition, 1913.

Black. William A Practical Treatise on Brewing. Forth Edition,

Longman, London, 1849.

Anon. The Young Brewers Monitor. London, 1824.

Accum. F. Treatise on The Art of Brewing. London, 1820.

Roberts. W.H. The Scottish Ale Brewer. Edinburgh and

London, 1837.

Whitbread's Brewery Records.

Mathias. P. The Brewing Industry in England 1700-1830.

Cambridge, UK, 1959.

Courage's Brewing Archive ..

Richardson. J. Statistical Estimates. 1784.

47

46

j

·1

Old British Beers and How to Make Them-Preamble

Most of these recipes are from the 18th century although there are a few gruit and

unhopped ale recipes that date back to the middle ages as well as a few 20th century

recipes. I have used these recipes and made some very nice ales. I would like to

mention that all recipes are given per 1 gallon of-finished product so you will need to

do some basic math to determine amounts needed for your batch size.

Hop AAs were about 4 to 5o/o in the days these beers were made, so ifyou are going

to use modem varieties with more AAs adjust accordingly. Many have noted that

the Fuggles and Goldings used almost exclusively in these beers provide a more

earthy/woody taste profile than other varieties. I'm just saying, if you want to get a

real idea of what these been were like, I would go with the specified hops.

All recipes call for a 3 hour mash. This was probably necessary with the malts

available in the 18tb century. Using modern (better-modified) malts, you can

probably get by with less than a 1 hour mash for OGs under 1.050 and up to a 2

hour mash for the very high-gravity recipes. Iodine test is the easiest way to verify

aU starches have been ~onverted. Some brewers have found that low-gravity beers

are fully saccharified in a 30 minute mash. However, most of these recipes are for

high-gravity beers so you may want to use up to a 2 hour mash. You can mow the

lawn and take out the trash while the mash is working.

I've included a hop-utilization table. You will notice that hop utilization is greatly

affected by wort gravity. These brews were made mostly with a 2 hour (or more)

boil. One reason was to get maximum hop utilization, the other was to reduce

volume in order to increase gravity. You may note that for all gravities, hop

utilization increases only about 10% between the first and second hour of the boil.

But you may also note that the hop utilization for a 1.040 brew is about double that

of a 1.120 brew.

There is a section on home-toasting malts in the oven. I have used this process and it

makes some unique flavors.

Make sure you use a yeast that is NOT overly-attenuative. These ales used a

relatively low-attenuating yeast strain that left a good amount of body and

sweetness. You will also note that a lot of these high-gravity brews were aged 8

months or more. Bow many of you can wait that long?

I

I

Table 7- Utilization as a function of Boil Gravity and Time

Iv~~a~~ , 1.030 , l.040 ,1.050 ,1.060 , 1 .070 , 1.080 , 1.090 , 1.100 , 1.110 , 1.120

I

I

I

I

I

I

0

1o.ooo 1o.ooo 1o.ooo 1o .ooo 1o.ooo 1~.ooo 1o.ooo 1o.ooo 1o.ooo 1o.ooo

5

1 o.o55

1o.o5o 1o .o46 1o.o42 1o .o38 1 o.o35 1o.o32 1o.o29 1o.o27 1 o.o25

10

1o.1oo 1o.o91 o.o84 1o.o76 1 o.o7o 1 o.o64 1o.o58 1o.o53 1 o.o49 1o.o45

15

1o.137 1o.125 o.114 l o.1o5 l o.o96 1o.o87 o.o8o o.o73 o.o67 o.o61

20

1o .167 1o.153 o.14o 1o .1 28_ 1o.117 1o.1o7 1o.o98 1o.o89 1o .o81 0.074

25

1o.192 1o.175 o.16o 1o.147 1o.134 10 .122 10.112 1o .1o2 l o .o94 0.085

30

10 .212 ! o.194 o .177 1o.162 ! o.148 1o.135 1o.124.1o.113 1o.1o3 0 .094

35

1o.229 o.2o9 o.191 1o.175 1o.16o 1o.146 1o.133 1o.122 0.111 0.102