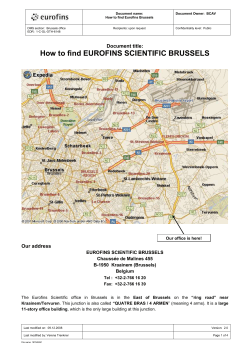

GUÉGUEN L IE AN