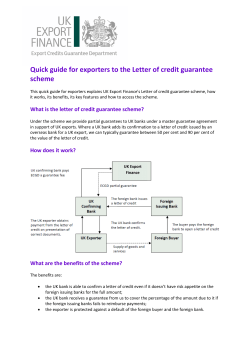

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from... National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Governance, Regulation, and Privatization