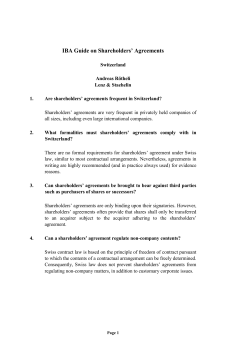

How to Kill the Scapegoat: Addressing View to Switzerland