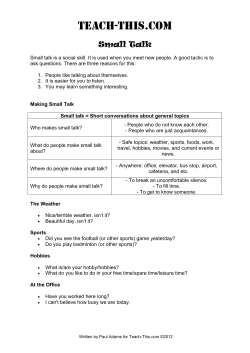

Document 185136