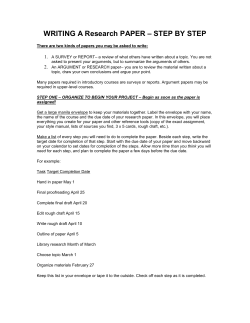

Open UP Study Skills How to Research