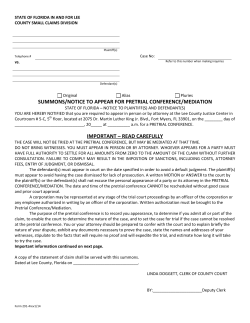

This panel will focus on the timing elements for successful... mediation, when and how to prepare for the mediation, when... DISCUSSION OUTLINE FOR