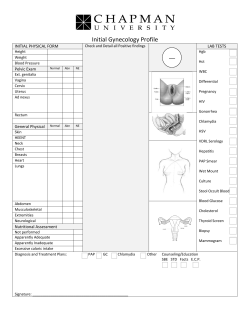

Sexually Transmitted Infections in Primary Care