Expert Review The Digital Rectal Examination

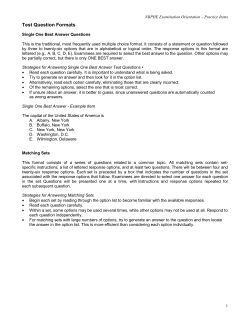

Expert Review The Digital Rectal Examination Anna Shirley* and Simon Brewster# …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. The Journal of Clinical Examination 2011 (11): 1-12 Abstract Digital rectal examination is an important skill for medical students and doctors. This article presents a comprehensive, concise and evidence-based approach to examination of the rectum which is consistent with The Principles of Clinical Examination [1]. We describe the signs of common and important diseases of the rectum and, based on a review of the literature, the precision and accuracy of these signs is discussed. Word Count: 2893 Key Words: digital rectal examination, rectum, anus Address for Correspondence: [email protected] Author affiliations: *Foundation Year 1 Doctor, Charring Cross Hospital, London. #Clinical Director of Urology, Oxford Radcliffe Hospitals NHS Trust. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Introduction The importance of performing a digital rectal examination (DRE) in the appropriate setting is captured by the phrase, “If you don’t put your finger in it, you put your foot in it.” – H. Bailey 1973 [2]. Anorectal or urogenital symptoms account for 510% of all general practice consultations [3] and the DRE is part of the assessment of these. In addition, statistics from 2008 show that colorectal and prostate cancer were the third and forth most commonly diagnosed cancers in the UK respectively (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer), [4] and 22% of colorectal cancers occur in the rectum [5]. DRE is an essential component of a complete abdominal examination (See The JCE Expert Review: Examination of the Gastrointestinal System [6]), a urological, and sometimes a gynaecological examination. The DRE is frequently cited by medical students as a way of completing the abdominal examination but it is often not performed in practice. However, it is essential that this skill is learned, as it is an important part of clinical examination for Foundation Doctors and beyond. A study of final year medical students at one UK medical school revealed that 42% had performed fewer than five DREs before qualifying, and lack of confidence in the skill was commonly reported [7]. The same study recorded that junior doctors perform DREs regularly, and this highlights the need for proficiency in this physical examination early in a medical career. The value of learning how to perform the DRE is increasingly being recognised across UK medical schools, and rectal examination mannequins are now used in student training and beyond. They may also be used to assess the skill in Objective Structured Clinical Examinations. The Context of the DRE There are many circumstances in which a DRE is considered to be appropriate. It has even been suggested that a DRE should be considered in all patients aged over 40 years who are admitted to hospital, unless there is a specific contraindication [8]. The most common presentations in which a DRE may be appropriate as part of their assessment are listed in Table 1. Anatomy of the Rectum and Anus Interpretation of findings on DRE requires knowledge of the anatomy of the rectum and anus, and of the surrounding structures. The rectum is approximately 12 cm long. It begins at the termination of the sigmoid colon and is continuous with the anal canal distally [5]. Anteriorly, the upper two-thirds of the rectum are covered with peritoneum. The anal canal is approximately 3-4cm long [9], and its skin merges with the perianal skin at the anal verge. There are two muscular anal sphincters: the internal anal sphincter, which is involuntary; and the external anal sphincter, which 1 is under voluntary control. The function of the rectum is to permit voluntary defaecation [5]. It is important to consider the anatomy of the rectum in relation to surrounding structures, which can be assessed when performing a DRE. In a male, the base of the bladder, prostate and urethra are situated anteriorly to the rectum, and in the female the cervix and vagina lie anteriorly. System Gastrointestinal Urological Other Symptoms/presentation Acute abdomen Change in bowel habit, faecal incontinence Rectal symptoms: bleeding, tenesmus Unexplained iron deficiency anaemia Unexplained weight loss Lower urinary tract symptoms Unexplained bone pain in males Gynaecological symptoms Trauma: secondary survey Neurological: suspected spinal cord pathology Table 1 Clinical presentations for which digital rectal examination should be considered. A clock face is traditionally used to describe the location of any lesions found during the DRE, as viewed in the lithotomy position (see Figure 1). 12 o’ clock is considered to be anterior, 3 o’ clock on the patient’s left, 6 o’ clock posteriorly and 9 o’ clock on the patient’s right. The distance of the lesion from the anus is also reported. The anal canal is lined with highly vascular anal cushions, which help with the maintenance of continence. Their arterial supply is from the rectal arteries, and they drain via the superior rectal vein. Haemorrhoids, one of the commonest pathologies of the anorectal region, are abnormal anal cushions with congested vasculature and dilated venous components. They typically occur at 3, 7 and 11 o clock. They are not palpable on DRE unless they are thrombosed, in which case a tense, tender swelling may be palpated. First degree haemorrhoids remain inside the anus, second degree haemorrhoids prolapse on straining but spontaneously return, and third degree haemorrhoids remain prolapsed unless manually returned. Prolapsed haemorrhoids may be visible on inspection during the DRE [10]. Figure 1 Describing the location of pathology of the rectum [13] Reproduced with permission. Literature Search The following textbooks of clinical examination were reviewed: Clinical Examination: A Systematic Guide to Physical Diagnosis [8] The Ultimate Guide to Passing Surgical Clinical Finals [9] Macleod’s Clinical Examination [11] Introduction to Clinical Examination [12] Clinical Examination [13] The PubMed database was searched using the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms alone or in combination: digital rectal examination, physical examination, rectum, sensitivity and specificity, statistics & numerical information, predictive value of tests. The free text terms: rectal, rectal cancer, prostate cancer, appendicitis, acute abdomen, trauma, examination, faecal incontinence were combined with the MeSH terms. Clinical prediction rules were searched for the rectum. The Rational Clinical Examination Series of the Journal of the American Medical Association; clinicalevidence.bmj.com and Evidence Based Medicine Online were searched with the terms ‘rectum’ and ‘digital rectal examination [14,15,16]. Related articles were also evaluated. Relevant articles available through Oxford University eresources were selected. 2 Preparation Ensure the examination environment is appropriate in terms of privacy. Wash your hands and introduce yourself to the patient. Check the patient’s identity, explain what you wish to do, and obtain consent for the procedure. Advise the patient that the examination should not feel painful, but that there may be some mild discomfort. The patient may also experience the desire to defaecate, and should be warned of this. A study of 269 patients investigating the acceptability of the DRE as part of prostate cancer screening found that 59.4% of patients considered this to be an acceptable examination, with the figure rising significantly to 91.5% after the examination [17]. This highlights the importance of explanation and reassurance before the examination. The DRE is considered an intimate examination, so it is important to offer a chaperone, as advised by the Medical Defence Union [18]. The name and role of the chaperone, or “chaperone was offered but declined”, should be documented in the notes. Gather the equipment needed, see Table 2. Equipment Needed for Digital Rectal Examination Non-sterile gloves Lubricant Jelly Cotton wool Tissue considered in the gynaecological setting for assessment of the pelvic organs [5]. Put on non-sterile gloves. Figure 2 Position of the patient when performing a digital rectal examination Initial Inspection The examination begins with an inspection of the natal cleft (the groove between the buttocks) and the anus and perianal skin. Part the buttocks gently and inspect the skin of the natal cleft from the sacrum to the perineum, and the anus (see Figure 3). Refer to Table 3 for a description of lesions that may be visible on initial inspection. In the presence of an anal fissure, the DRE may be exquisitely tender, so it may be appropriate to anaesthetise the area with lidocaine gel beforehand [12]. Table 2 Equipment needed for a digital rectal examination Position of the patient Ask the patient to undress from the waist downwards, including undergarments. He/she should be allowed to do this in private and a gown used to preserve modesty until the examination is performed. The patient should be positioned lying on the couch in the left lateral position, facing away from the examiner (see Figure 2). Ask the patient to draw his/her legs up towards the body. An alternative, but less favoured approach, is to ask the patient to stand over the examining couch in a bent over position with his/her elbows resting on the couch. Although useful for assessing the prostate, it is inadequate for assessing the rectum as a whole [19]. However, this position may be more suitable for the elderly or those with reduced mobility. The lithotomy position is another alternative and may be Figure 3 Initial inspection of the natal cleft The patient should then be asked to strain, or ‘bear down’. Observe the descent of the perineum. Excessive descent suggests a laxity of the perineum. Look for any sign of rectal prolapse (which in the early stages is just mucosal) or prolapse of haemorrhoids. Rectal prolapse originates from the rectum, higher than the origin of haemorrhoids, and appears as a mass with 3 concentric rings of mucosa, whereas haemorrhoids exhibit radial folds. However, it is not always easy to tell them apart; they may coexist, and a contrast defecogram (a radiological study) may be required to diagnose rectal prolapse. Look also for a patulous anus, which appears wide open and is due to reduced tone in the sphincter muscles, and for any sign of faecal incontinence [19]. Pathology of the Natal Cleft and Anus Viral warts Skin tags Anal fissures Fistulae External Haemorrhoids Rectal Prolapse Crohn’s disease Dermatitis Anal Carcinoma Description Papillomata with a rough, white surface surrounding the anus Pedunculated, fleshcoloured perianal skin growths Tear in the anal wall, commonly posteriorly in the midline. The opening may be visible as a red, pouting structure near the anus Bluish swellings protruding from the anus Folds of red mucosa protruding from the anus Blue-tinged perianal skin, fistulae, fissures, skin tags Red, inflamed skin Mass may be visible at the anal verge Palpation Lubricate the index finger of your gloved right hand with a water-based lubricant such as K-Y Jelly. Kneel down bedside the examination couch. Warn the patient that you are about to examine the rectum. Place the gloved finger on the anal margin and gently apply pressure to enter the anal canal and rectum. To begin with, the pulp of the examining finger should be facing the 6 o clock position (see Figure 5a). Aim your finger slightly posteriorly, following the curve of the sacrum [8]. Figure 4 Testing perianal sensation: dermatomes S2,S3,S4. Adapted from reference 13 [13]. Table 3 Pathology of the Natal Cleft and Anus. Adapted from References 8 and 13 [8,13]. Sensation and the Perineal Reflex The sensory dermatomes of the perianal region are S2, S3 and S4. To test sensation, use cotton wool to stroke lightly the areas that correspond to these dermatomes (see Figure 4) and ask the patient if he/she can feel the cotton wool in each of these areas. To test the perineal reflex (anal reflex, anal wink), use cotton wool to stroke the skin immediately around the anus, and observe for contraction of the anus (by the anal sphincter muscles). Impaired perianal sensation and an absent or reduced perineal reflex may indicate S2-4 nerve root or spinal cord pathology, for example cauda equina syndrome, in which the sacral nerve roots may be compressed. A more detailed neurological examination may be then be required Figure 5a Palpation of the rectum in the 6 o’clock position Assessment of Anal Tone On entering the anal canal, an initial judgment of the anal tone at rest can be made. Then ask the patient to ‘bear down’ and squeeze your finger, to assess the anal sphincter further in terms of strength and symmetry. Reduced or absent tone may indicate 4 spinal cord injury. DRE has traditionally been considered a part of the secondary survey of the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol to examine for this [20], as well as to detect a “high-riding” prostate (the prostate is difficult to feel or only its base is palpable) in males with urethral injury, and to determine if a pelvic fracture is open (to the gastrointestinal tract), or closed. Few studies have assessed how useful the DRE is for detecting spinal cord injury, but there is evidence to suggest that its findings must be considered in the context of other clinical signs, and in the absence of reduced anal tone, spinal cord injury cannot be excluded (see Evidence Box 1). Assessment of anal tone is also used in the evaluation of faecal incontinence, and findings on DRE have been shown to correlate well with recordings from anal manometry [22,23]. Palpation of the Rectum Normally, the coccyx and sacrum can be felt posteriorly. Different authors disagree about the direction in which to palpate the circumference of the rectum, though the most important point is that the entire rectum must be palpated [8,9,11-13]. A popular way is described here. From the 6 o’clock position, supinate your arm to examine the right posterolateral rectal wall, until the 9 o’ clock position is reached. Return to the 6 o clock position, and pronate your arm 90° to the 3 o’ clock position to examine the left posterolateral rectal wall. Continue pronating your arm round to the 12 o’clock position, and beyond this to the 9 o’clock position, to examine the anterolateral rectal walls. Return to the 12 o’clock position (see Figure 5b). The entire rectum is therefore assessed for tenderness and any palpable masses. This may detect a rectal carcinoma, which feels hard and irregular, however there are many causes of a palpable rectal mass (see Table 4). There is little evidence available as to how useful the DRE is for detecting rectal carcinoma, but one study in the setting of general practice concluded that it should not be relied upon alone (see Evidence Box [24]. The rectum may be loaded with faeces, which is a common finding in patients with constipation. These are typically moveable and indentable [11]. In the presence of a palpable rectal mass, it may be appropriate to repeat the examination after the patient has defaecated, to exclude faeces as a cause. Note that haemorrhoids are not palpable on DRE unless they are thrombosed. In addition to palpable masses, stenosis of the anal canal or rectum can be felt as a tight, narrow region and may indicate anal, rectal or prostate carcinoma. Figure 5b Palpation of the rectum in the 12 o’clock position Site of origin of pathology Rectum Sigmoid colon Pelvis Prostate Mass Faeces Rectal carcinoma Rectal polyp Foreign body Prolapsed sigmoid carcinoma Pelvic metastases Uterine malignancy Ovarian Malignancy Cervical carcinoma Endometriosis Pelvic Abscess Prostate carcinoma Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy Prostatic Abscess Table 4 Causes of a palpable mass on digital rectal examination. Adapted from Reference 8[8]. The DRE is performed on nearly all patients presenting with an acute abdomen, and the presence of tenderness has been reported to be one of the more useful signs identified during this examination [5]. It may indicate the presence of inflammatory bowel disease, prostatitis, ovarian abscesses and cysts, and appendicitis. However, the evidence for the latter is variable, and suggests that the DRE is not very sensitive for detecting appendicitis, and provides additional useful information only if the diagnosis is in doubt following history taking and examination of the abdomen, in which case other pathology should be suspected (see Evidence Box 3) [25,26,27] 5 Prostate examination The prostate is examined in males at the end of the rectal examination when the examining finger is in the 12 o’ clock position. One small study using a DRE simulator found that a higher magnitude of finger pressure led to the detection of smaller prostate abnormalities, so it is important to ensure adequate pressure when palpating the prostate [28]. The prostate should be assessed for consistency, nodularity, size and symmetry. The normal prostate feels firm with a smooth, regular surface and is symmetrical [29]. It is approximately 3.5cm wide and protrudes approximately 1cm into the rectal lumen. There are two lobes separated by a palpable longitudinal sulcus. It is not always possible to feel the base of the gland but if it is small one can easily get above it. Enlargement of the prostate gland occurs in benign prostatic hypertrophy, and its smooth, symmetrical properties are typically maintained. Prostate size determined by digital rectal examination has been found to correlate significantly with transrectal ultrasound measurements, though gives a slight underestimate for larger sizes [30] Prostate cancer is suggested by a hard, irregular asymmetrical prostate, with the sulcus not palpable between the lobes. A number of meta-analyses have evaluated the role of the DRE in detecting prostate cancer, and though the DRE is considered a vital part of the work up for a patient with suspected prostate pathology, evidence suggests its findings must be considered in the context of investigations such as the prostate specific antigen (PSA) measurement and ultrasound scan (see Evidence Box 4) [31,32,33]. DRE has also been found to detect prostate cancer in the presence of PSA levels that are not raised [34]. However the majority of cancers currently diagnosed are in the early stages and are not palpable. The prostate gland is typically not tender, and tenderness may suggest acute prostatitis or a prostatic abscess. Further tests There is also the option of testing for pelvic floor dyssynergia, in which the external anal sphincter contracts instead of relaxes when the patient strains to defaecate. This is a common cause of chronic constipation. To test for this, ask the patient to strain trying to push your finger out. Paradoxical tightening of the musculature suggests dyssynergia. The DRE has been shown to be a very useful test for identifying this (see Evidence Box 5) [35]. Completing the Examination Always inspect the gloved finger for the nature and colour of the stool, and note the presence of any blood or mucus. Black tarry stools may represent melaena, which occurs as the breakdown product of blood, indicating an upper gastrointestinal bleed. The stool may also appear dark if the patient is taking oral iron supplements. Pale, offensive stools occur in situations of malabsorption. Pale stools may also be found in patients with obstructive jaundice, along with dark urine. Fresh blood on the surface of, or mixed in with stool suggests bleeding from the large bowel, rectum or anus. There is also the option for performing a faecal occult blood test (FOBT) at this stage, as part of a screening process for colorectal cancer. A single sample of the stool obtained during DRE on the gloved finger is smeared on to a faecal occult blood test card. However, this is less commonly performed now as it is considered inferior to the recommended sampling practice using the guaiac smear method, which tests 3 naturally passed stools on consecutive days (see Evidence Box 6) [36]. Once the DRE is complete, wipe away the lubricant jelly and direct the patient to redress. Remove your gloves and wash your hands. Conflicts of Interest None declared. 6 References [1] Jopling H. The Principles of Clinical Examination. The Journal of Clinical Examination. 2006; 1: 1-6 [2] Bailey H. Demonstrations of Physical Signs in Clinical Surgery (1973) Fifteenth Edition. Publisher: Wright, Bristol [3] van Driel MF, van Andel MV, ten Cate Hoedemaker HO, Wolf RF, Mensink HJ. Physical Diagnosis-Digital Rectal Examination. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2002 Mar 16;146(11):508-12 [4] http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/inciden ce/commoncancers [5] McFarlane MJ. The Rectal Examination. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Chapter 97 [6] Gardner A. Examination of the Gastrointestinal System. The Journal of Clinical Examination 2006; 1: 7-11 [7] Turner KJ, Brewster SF. Rectal Examination and Urethral Catheterization by Medical Students and House Officers: Taught but not Used. BJU Int. 2000 Sep;86(4):422-6 [8] Clinical Examination: A Systematic Guide to Physical Diagnosis. Talley NJ, O’Connor S (2009) Sixth Edition. Publishers: Churchill Livingstone [9] The Ultimate Guide to Passing Surgical Clinical Finals. Malik MF, Maula A (2010) First Edition. Publishers: Radcliffe Publishing [10] Surgical Talk. Goldberg A, Stansby G (2008) Second Edition. Publishers: Imperial College Press [11]. Macleod’s Clinical Examination. Douglas G, Nicol F, Robertson C (2009) Twelfth Edition. Publishers: Churchill Livingstone [12] Introduction to Clinical Examination. Ford M, Japp A, Hennessey I (2005) Eighth Edition. Publishers: Churchill Livingstone [13] Clinical Examination. Epstein O, Perkin GD, Cookson J, Watt IS, Rakhit R, Robins AW, Hornett GAW (2008) Fourth Edition. Publishers: Mosby. Article Title: Examining the anus, rectum and prostate p223-224. Copyright Elsevier 2008 [14] The Journal of the American Medical Association Rational Clinical Examination Series http://jama.amaassn.org/cgi/collection/rational_clinical_exam [15] clinicalevidence.bmj.com [16] Evidence Based Medicine Online, British Medical Journal, http://ebm.bmj.com/ [17] Furlan AB, Kato R, Vicentini F, Cury J, Antunes AA, Srougi M. Patients’ Reactions to Digital Rectal Examination of the Prostate. Int Braz J Urol. 2008 Sep-Oct;34(5):572-5 [18] www.the-mdu.com [19] Talley NJ. How to do and Interpret a Rectal Examination in Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Apr;103(4):820-2 [20] Guldner GT, Brzenski AB. The Sensitivity and Specificity of the Digital Rectal Examination for Detecting Spinal Cord Injury in Adult Patients with Blunt Trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 2006 Jan;24(1):113-7 [21] Shlamovitz GZ, Mower WR, Bergman J, Crisp J, DeVore HK, Hardy D, Sargent M, Shroff SD, Snyder E, Morgan MT. Poor Test Characteristics for the Digital Rectal Examination in Trauma Patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2007 Jul;50(1):25-33, 33.e1 [22] Buch E, Alós R, Solana A, Roig JV, Fernández C, Díaz F. Can Digital Examination Substitute Anorectal Manometry for the Evaluation of Anal Canal Pressures? Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1998 Feb;90(2):85-93 [23]Dobben AC, Terra MP, Deutekom M, Gerhards MF, Bijnen AB, Felt-Bersma RJ, Janssen LW, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. Anal Inspection and Digital Rectal Examination Compared to Anorectal Physiology Tests and Endoanal Ultrasonography in Evaluating Fecal Incontinence. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007 Jul;22(7):783-90. Epub 2006 Nov 10 [24] Ang CW, Dawson R, Hall C, Farmer M. The Diagnostic Value of Digital Rectal Examination in Primary Care for Palpable Rectal Tumour. Colorectal Dis. 2008 Oct;10(8):789-92 [25] Dickson AP, MacKinlay GA. Rectal Examination and Acute Appendicitis. Arch Dis Child. 1985 Jul;60(7):666-7 [26] Dixon JM, Elton RA, Rainey JB, Macleod DA. Rectal Examination in Patients with Pain in the Right Lower Quadrant of the Abdomen. BMJ. 1991 Feb 16;302(6773):386-8 [27] Sedlak M, Wagner OJ, Wild B, Papagrigoriades S, Zimmermann H, Exadaktylos AK. Is There Still a Role for Rectal Examination in Suspected Appendicitis in Adults? Am J Emerg Med. 2008 Mar;26(3):359-60 7 [28] Wang N, Gerling GJ, Krupski TL, Childress RM, Martin ML. Using a Prostate Exam Simulator to Decipher Palpation Techniques that Facilitate the Detection of Abnormalities Near Clinical Limits. Simul Healthc. 2010 Jun;5(3):152-60 [29] Deshpande AR, Block N, Barkin JS. Taking a Closer Look at the Rectal Examination: Beyond the Basics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jan;104(1):246-7 [30] Roehrborn CG, Girman CJ, Rhodes T, Hanson KA, Collins GN, Sech SM, Jacobsen SJ, Garraway WM, Lieber MM. Correlation Between Prostate Size Estimated by Digital Rectal Examination and Measured by Transrectal Ultrasound. Urology. 1997 Apr;49(4):548-57 [31] Hoogendam A, Buntinx F, de Vet HC. The Diagnostic Value of Digital Rectal Examination in Primary Care Screening for Prostate Cancer: a meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 1999 Dec;16(6):621-6 [32] Mistry K, Cable G. Meta-Analysis of ProstateSpecific Antigen and Digital Rectal Examination as Screening Tests for Prostate Carcinoma. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003 Mar-Apr;16(2):95-101 [33] Song JM, Kim CB, Chung HC, Kane RL. Prostate-Specific Antigen, Digital Rectal Examination and Transrectal Ultrasonography: A Meta-Analysis for this Diagnostic Triad of Prostate Cancer in Symptomatic Korean Men. Yonsei Med J. 2005 Jun 30;46(3):414-24 [34] Okotie OT, Roehl KA, Han M, Loeb S, Gashti SN, Catalona WJ. Characteristics of Prostate Cancer Detected by Digital Rectal Examination Only. Urology. 2007 Dec;70(6):1117-20 [35] Tantiphlachiva K, Rao P, Attaluri A, Rao SS. Digital Rectal Examination is a Useful Tool for Identifying Patients with Dyssynergia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Nov;8(11):955-60. Epub 2010 Jul 23 [36] Collins JF, Lieberman DA, Durbin TE, Weiss DG. Accuracy of Screening for Fecal Occult Blood on a Single Stool Sample Obtained by a Digital Rectal Examination: a Comparison with Recommended Sampling Practice. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Jan 18:142(2):81-5 8 Question. Does this patient have spinal cord injury based on findings from the DRE? Reference. Guldner and Brzenski (2006) [20]. Population. 1032 patients over 15 years of age with blunt trauma. Incidence. 5.2% Details of Study. Retrospective review. Comparator. Diagnosis of Spinal Cord Injury on discharge, according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). Sensitivity. See Table Specificity. See Table. Conclusion. The DRE is insensitive to spinal cord injury, but highly specific. A negative DRE cannot rule out spinal cord injury. Reduced or absent rectal tone on DRE should be interpreted in the context of the pre-test probability of spinal cord injury. Question. Does this patient have spinal cord injury based on findings from the DRE? Reference. Shlamovitz et al (2007) [21]. Population. 1401 Incidence. 3% Details of Study. Retrospective medical record review. Comparator. Spinal cord injury on imaging or operation reports, or new parapleagia/quagriplegia/spinal injury diagnosis. Sensitivity. See Table Specificity. See Table. Conclusion. Due to its poor sensitivity for detecting spinal cord injury, the DRE should not be used as a screening tool in trauma cases. The DRE cannot rule out spinal cord injury. Author Guldner GT 2006 [20] Schlamovitz GZ 2007[21] N 1032 1401 Sensitivity (%) 50 37 Specificity (%) 93 96 Evidence Box 1 The digital rectal examination in spinal cord injury. Question. Does this patient have a rectal tumour on DRE by the general practitioner? Reference. Ang et al (2008) [24]. Population. 1069 patients referred to the colorectal cancer referral service by GPs. Incidence. 3.93% Details of Study. Retrospective review of hospital data. Comparator. DRE performed in the specialist clinic. Sensitivity. 76.2% Specificity. 91.7% Conclusion. In the primary care setting, although the specificity and sensitivity of DRE for detecting rectal tumours are high, there was a high false positive rate, so DRE should not be used alone in the diagnosis of a rectal tumour, but in the context of other findings. Evidence Box 2 Identifying a rectal tumour on digital rectal examination. 9 Question. Does this patient have appendicitis based on DRE? Reference. Dickson et al (1985) [25]. Population. 328 patients aged 14 and under with suspected appendicitis. Incidence. 31.4% Details of Study. Prospective study. Comparator. Histology of resected appendix Sensitivity. See table. Specificity. See table. Conclusion. More than 90% were correctly diagnosed with appendicitis based on history and abdominal signs alone, without information from DRE. DRE may therefore be more useful if the diagnosis remains uncertain after this initial assessment and other pelvic pathology is suspected. Question. Does this patient have appendicitis based on DRE? Reference. Dixon et al (1991) [26]. Population. 1028 patients with right lower quadrant pain who underwent DRE. Incidence. 37.3 Details of Study. Prospective study. Comparator. Histology of resected appendix. Sensitivity. See table. Specificity. See table. Conclusion. Although tenderness on DRE was more common in patients with appendicitis than other diagnosed conditions, if rebound tenderness was present, the DRE provided no further useful information. Question. Does this patient have appendicitis based on DRE? Reference. Sedlak et al (2007) [27]. Population. 577 patients aged over 16 with right lower quadrant pain who underwent DRE Incidence. 40.4% Details of Study. Retrospective review of medical records. Comparator. Histology of resected appendix Sensitivity. See table. Specificity. See table. Conclusion. The DRE is not helpful in making the diagnosis of appendicitis or in guiding the decision whether to proceed to surgery. Author Dickson 1985 [25] Dixon 1991 [26] Sedlak 2007 [27] N 328 1401 577 Sensitivity(%) 9 34 36.5 Specificity(%) 88 72 61.5 Evidence Box 3 Identifying appendicitis on digital rectal examination. 10 Question. Does this patient have prostate cancer on DRE? Reference. Hoogendam et al (1999) [30]. Population. ~22,000 men from unselected populations. Incidence. 1.2 – 7.3% Details of Study. Metaanalysis of 14 studies, 5 considered ‘good quality’. Comparator. Prostate biopsy or surgery. Sensitivity. See Table. Specificity. See Table. Conclusion. DRE is highly specific for the detection of prostate cancer but the sensitivity is low. It should not be used alone to diagnose or exclude prostate cancer. Question. Does this patient have prostate cancer on DRE? Reference. Mistry and Cable (2003) [31]. Population. 47,791 men. Most studies included asymptomatic men aged over 50 years. Incidence 1.8% Details of Study. Meta-analysis of 13 studies. Comparator. Prostate biopsy. Sensitivity. See Table. Specificity. See Table. Conclusion. Prostate specific antigen measurement had a higher sensitivity and specificity for detecting cancer than did DRE. PSA and DRE together detected 83.4% of early, localised prostate cancer. Question. Does this patient have prostate cancer on DRE? Reference. Song et al (2005) [32]. Population. 2029 men with lower urinary tract symptoms or benign prostatic hyperplasia. Incidence. 25.4% (13.5-41.5%). Details of Study. Meta-analysis of 13 studies. Comparator. Prostate biopsy. Sensitivity. See Table. Specificity. See Table. Conclusion. The findings on DRE are best considered as part of a triad along with Prostate Specific Antigen measurement and Transrectal Ultrasound scanning. Author Hoogendam A 1999[30] Hoogendam A 1999[30] Mistry K 2003[31] Song JM 2005[32] Studies 14 5 good quality 13 13 Sensitivity(%) 59 64 53.2 68.4 Specificity(%) 94 97 83.6 71.5 Evidence Box 4 Identifying prostate cancer on digital rectal examination. Question. Does this patient have dyssynergia? Reference. Tantiphlachiva et al (2010) [35]. Population. 209 consecutive patients with Rome III criteria for chronic constipation Incidence. 87% Details of Study. Prospective study. Comparator. Physiological test results Sensitivity. 75% Specificity. 87% Conclusion. The DRE is a useful tool in identifying patients with dyssynergia, and could help select patients for further investigation and treatment. Evidence Box 5 Identifying dyssynergia on digital rectal examination. 11 Question. Is a stool sample obtained by DRE as accurate as naturally passed stool for faecal occult blood test (FOBT) sampling when screening for colorectal cancer? Reference. Collins et al (2005) [36]. Population. 2665 asymptomatic patients aged 50-75. Incidence. 10.7% Details of Study. Prospective cohort study. Comparator. Colonoscopy. Sensitivity. See table. Specificity. See table. Conclusion. Digital FOBT is a poor screening tool for colorectal cancer, and a negative result cannot exclude advanced disease. Alternative tests such as the at-home 6 sample FOBT are preferred, and the digital FOBT should not be used alone. Method of FOBT Digital FOBT At-home 6 sample FOBT Sensitivity (%) 4.9 23.9 Specificity (%) 97.5 93.9 Evidence Box 6 Comparing methods of obtaining stool sample for faecal occult blood testing 12

© Copyright 2026