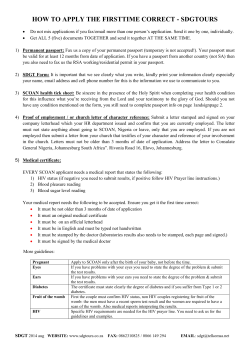

Gender Integrate How to