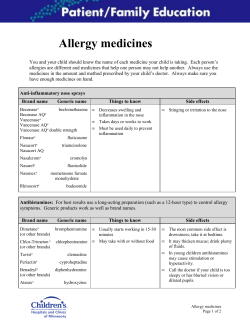

G